-

Despite rhetoric from some politicians that decades of unfettered globalization have hollowed out the U.S. industrial base, the United States remains a manufacturing powerhouse, accounting for a larger share of global output than Japan, Germany, and South Korea combined. In key industries such as autos and aerospace, the United States ranks among the global leaders and is the second-largest manufacturing economy overall.

-

That manufacturing employs fewer Americans and accounts for a lower percentage of gross domestic product than in decades past is not cause for serious concern, unique to the United States, or primarily owed to globalization. These trends have instead been largely driven by productivity gains and shifting consumer preferences in favor of services.

-

The premium placed by policymakers on manufacturing employment is misplaced. Unlike most of the post–World War II era, jobs in this sector now provide lower compensation than similar roles elsewhere in the economy, while the diversified nature of the U.S. economy is a source of economic resiliency, not weakness.

An unfortunate perception among many commentators and political leaders is that the United States “doesn’t make anything anymore.” According to this narrative, the country is a former manufacturing titan brought low by the forces of globalization that have left the rusting hulks of once-humming factories in its wake. Instead of producing their wares in locations such as Pittsburgh and Peoria, some globalization critics claim U.S. corporations have shifted their operations to take advantage of vastly lower wages in China, Mexico, and elsewhere. Factory closures, these critics insist, have forced American workers to trade well-paid work on the assembly line for less financially rewarding jobs in the service sector. In this telling, trade liberalization’s legacy is one of industrial decline, wrecked lives, and ruined communities.

Reports of American manufacturing’s death, however, are greatly exaggerated. While it is undeniably true that certain manufacturing industries—particularly labor-intensive, low-tech ones—are no longer primarily located in the United States, many other, more advanced ones have flourished. Thus, factories producing consumer staples such as textiles and furniture, for example, have made way for facilities that produce products less often found in retail stores, such as chemicals and machinery. At the same time, productivity gains unleashed by automation and other technologies have enabled manufacturing output to remain near record highs even as direct manufacturing employment has declined. Many other Americans, meanwhile, still work in manufacturing or are involved in the manufacturing process through the design of new products, even if their employers don’t operate actual factories.

In short, manufacturing in the United States has not disappeared but has been transformed and very much remains a vital part of the country’s economic fabric.

Deindustrialization Worries Are Nothing New

Politicians have sought to advance and capitalize on worries of industrial decline for decades. During his 1984 presidential campaign, Walter Mondale told steelworkers in Cleveland that President Ronald Reagan’s policies were “turning our industrial Midwest into a “rust bowl”—a turn of phrase soon modified and popularized by the media as “Rust Belt.” This region’s misfortunes—and the broader alleged plight of American manufacturing—have been an enduring feature of the political discourse ever since.

Some of this focus is the natural result of politicians’ and the media’s long-standing attraction to bad news and nostalgia: Factory closures make news (or even movies); factory expansions don’t. And the industrial Midwest’s long-standing importance to the U.S. presidential election means that the region will always receive outsized political attention, regardless of economic realities elsewhere in the country.

Yet certain statistics also lend a superficial plausibility to claims of domestic manufacturing’s dire state. U.S. manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 at 19.5 million employees, stood at just over 17 million in 2000, and has since dropped to approximately 13 million as of January 2023. In relative terms, the percentage of workers employed in manufacturing has more than halved since 1980 as did its share of gross domestic product (GDP) from 1978 to 2018.

Such declines also correlate with a growing embrace of trade liberalization over this period via such initiatives as the North American Free Trade Agreement, conclusion of the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations and agreement to establish the World Trade Organization (WTO), and China’s accession to the WTO (although the decline was already underway when each of these took place).

No great effort is therefore required to grasp why many Americans believe that the country’s industrial sector—and the well-paying jobs that go with it—has received a hammer blow at the hand of globalized commerce more generally and China in particular. But that doesn’t mean it’s true. A fuller and more accurate picture reveals a sector in remarkably good health whose indications of decline are far less worrisome when placed in proper context.

What Is Manufacturing?

Before delving into the state of U.S. manufacturing, it is worth examining what the industry entails. Although the term may conjure images of glowing hot steel or new automobiles rolling off the assembly line, manufacturing runs a wide gamut of activities. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, manufacturers are “… establishments engaged in the mechanical, physical, or chemical transformation of materials, substances, or components into new products.” These include not only the production of heavy machinery and sophisticated devices but also other items, such as fruit and vegetable preserves, stationary, and beverages. By this definition, Coca-Cola is every bit the manufacturer as Boeing, General Motors, or U.S. Steel.

But the dividing line can sometimes be ambiguous. U.S.-headquartered Nike, for example, engages in the design and marketing—key parts of the manufacturing process—of footwear, apparel, and sports equipment. The actual production of these items, however, is outsourced to independent contractors. Global semiconductor leader Nvidia follows much the same approach. Should these “factoryless goods producers” be considered manufacturers? So far, the government’s answer is no. Nevertheless, such firms are key contributors to the manufacturing process and generate considerable value, jobs, and innovations.

The United States Remains a Manufacturing Powerhouse

Regardless of how one defines manufacturing, the United States is clearly one of its heavy hitters. In 2021, it ranked second in the share of global manufacturing output at 15.92 percent—greater than Japan, Germany, and South Korea combined—and the sector by itself would constitute the world’s eighth-largest economy. The United States was the world’s fourth-largest steel producer in 2020, second-largest automaker in 2021, and largest aerospace exporter in 2021.

That the United States has achieved these rankings with a relatively small industrial workforce is a testament to its world-beating productivity: the country ranks number one in real manufacturing value-added per worker by a large margin. With value-added of over $141,000 per worker in 2019, the United States bested second-ranked South Korea by over $44,000. The gap with China was over $120,000 per worker (Figure 1).

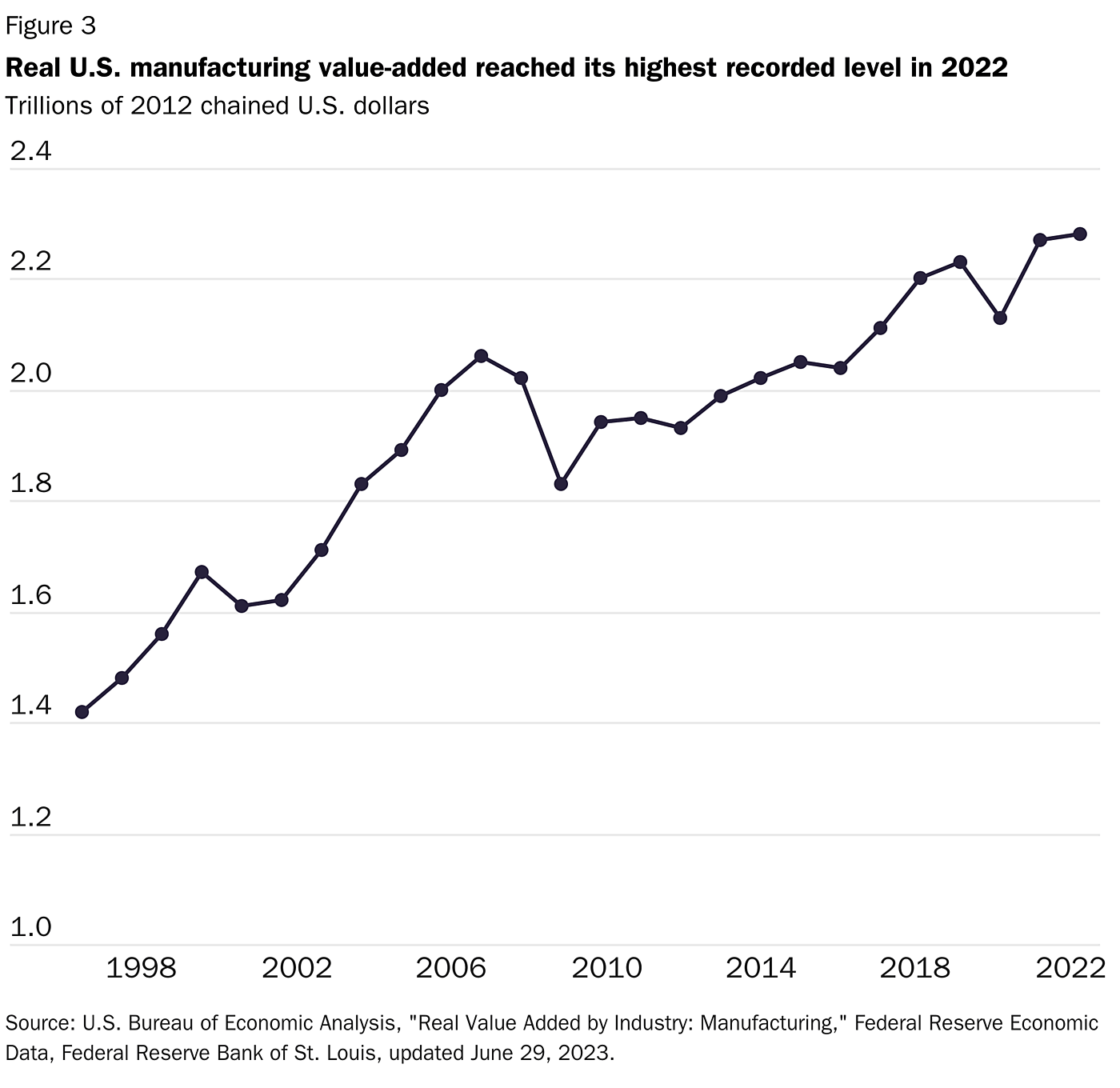

Manufacturing output has also remained strong in historical terms, at only 5 percent lower than its all-time high achieved in the final quarter of 2007 (Figure 2). Measured by real value-added, the sector reached its highest level in 2022 (Figure 3).

The country’s industrial prowess is also evidenced by foreigners’ appetite for investment in U.S. manufacturing. As of 2021, the stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the sector stood at over $2.1 trillion, while 2021 also saw $121.3 billion of new FDI flow into domestic manufacturing—an amount greater than any other industry.

Beyond their direct investment in the sector, foreigners are also eager consumers of U.S. manufactured products. In 2018, the United States ranked second in the world in merchandise exports and third for exports of “manufactures,” and from 2002 to 2021, the country’s manufacturing exports more than doubled. In 2019, U.S. firms exported over $1.3 trillion in manufactured goods, including aerospace and aircraft parts ($60.1 billion), integrated circuits ($41.2 billion), and medical instruments ($29.4 billion). According to the World Bank, approximately 20 percent of all U.S. manufactured goods exports in 2021—totaling more than $169 billion—were “high technology” products (i.e., “products with high [research and development] intensity, such as in aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments, and electrical machinery”).

Among the destinations for these goods are other leading manufacturing countries. In 2020, for example, the United States exported $17 billion worth of electrical machinery to China, $6.6 billion in optical and medical instruments to Japan, and $16 billion worth of transportation equipment to Germany. The previous year, the European Union alone imported $35.7 billion worth of aircraft from the United States.

That so many Americans fail to appreciate the vast size and scale of U.S. manufacturing is perhaps at least partially explained by the fact that many retail purchases by consumers are for products imported from abroad. But much of what U.S. manufacturers make are items whose production requires advanced know-how that consumers rarely encounter. In 2020, for example, the United States was the world’s leading exporter of medical instruments, gas turbines, and aircraft parts—goods not often found on retail store shelves.

The Role of Productivity

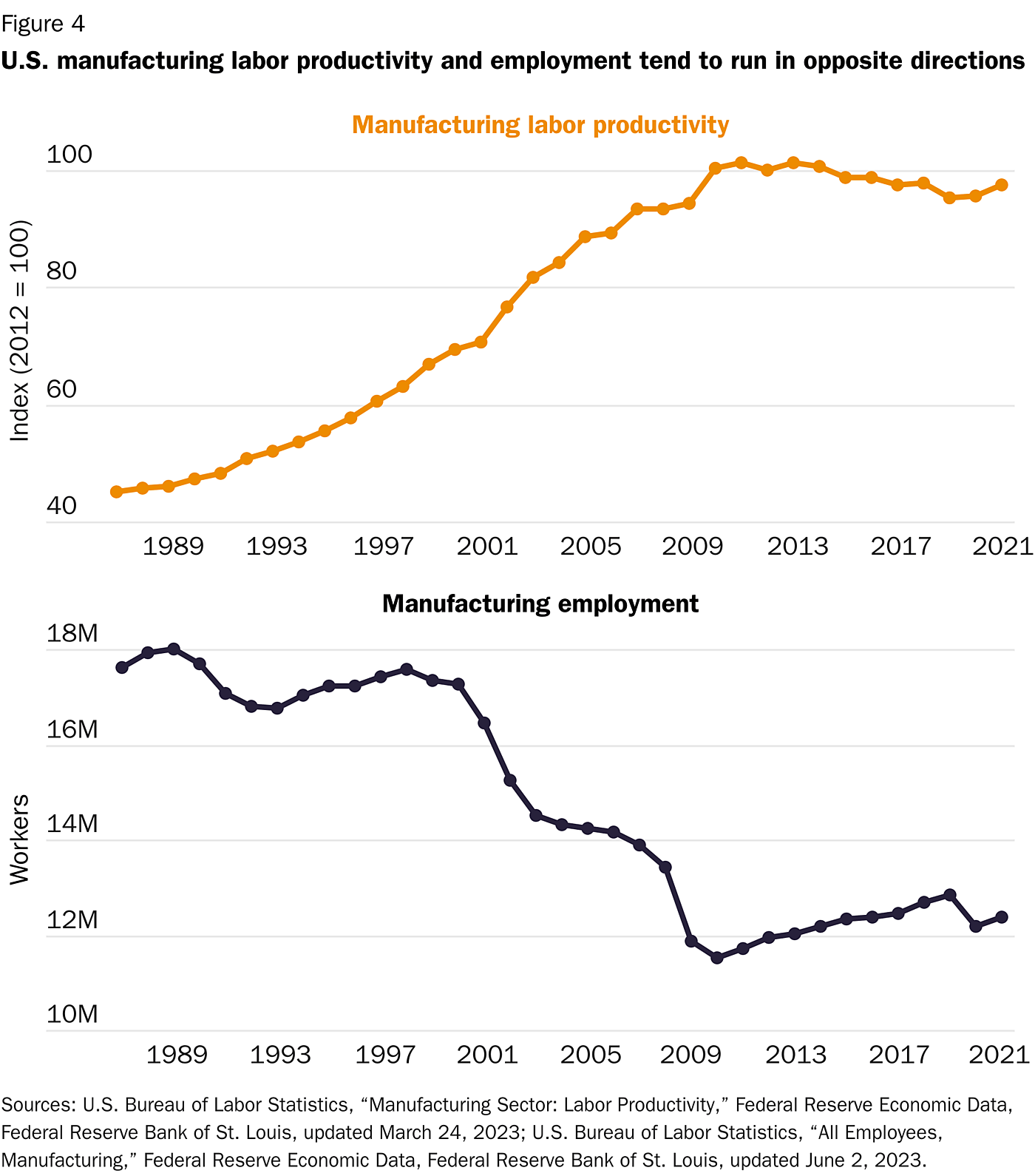

Another possible driver of manufacturing pessimism is the decline in employment in the sector, with the number of workers falling by over 6 million since 1979 and from nearly 25 percent of all workers in 1973 to just over 10 percent in 2016. That U.S. manufacturing still maintains high output despite such workforce reductions is largely due to labor productivity—robots, computers, process improvements, etc.—that has nearly doubled since 2000. U.S. manufacturing firms, assisted by industrial robots and other production process improvements, have managed to increase production with fewer workers. The U.S. steel industry, for example, had 14 percent higher output in 2018 than 1980 even while employment over the same period shrank from nearly 399,000 workers to 83,000.

In fact, a 2015 study found that 88 percent of manufacturing job losses from 2000 to 2010 can be attributed to improved productivity. Although other studies assign a larger role to trade and the advent of China as an efficient manufacturing hub, there are few who deny the role of productivity improvements as a significant, if not main, factor behind the long-term decline in manufacturing employment. Supporting this conclusion is the fact that the United States added 1.3 million manufacturing jobs between 2009 and 2019 amid stagnating manufacturing productivity (Figure 4).

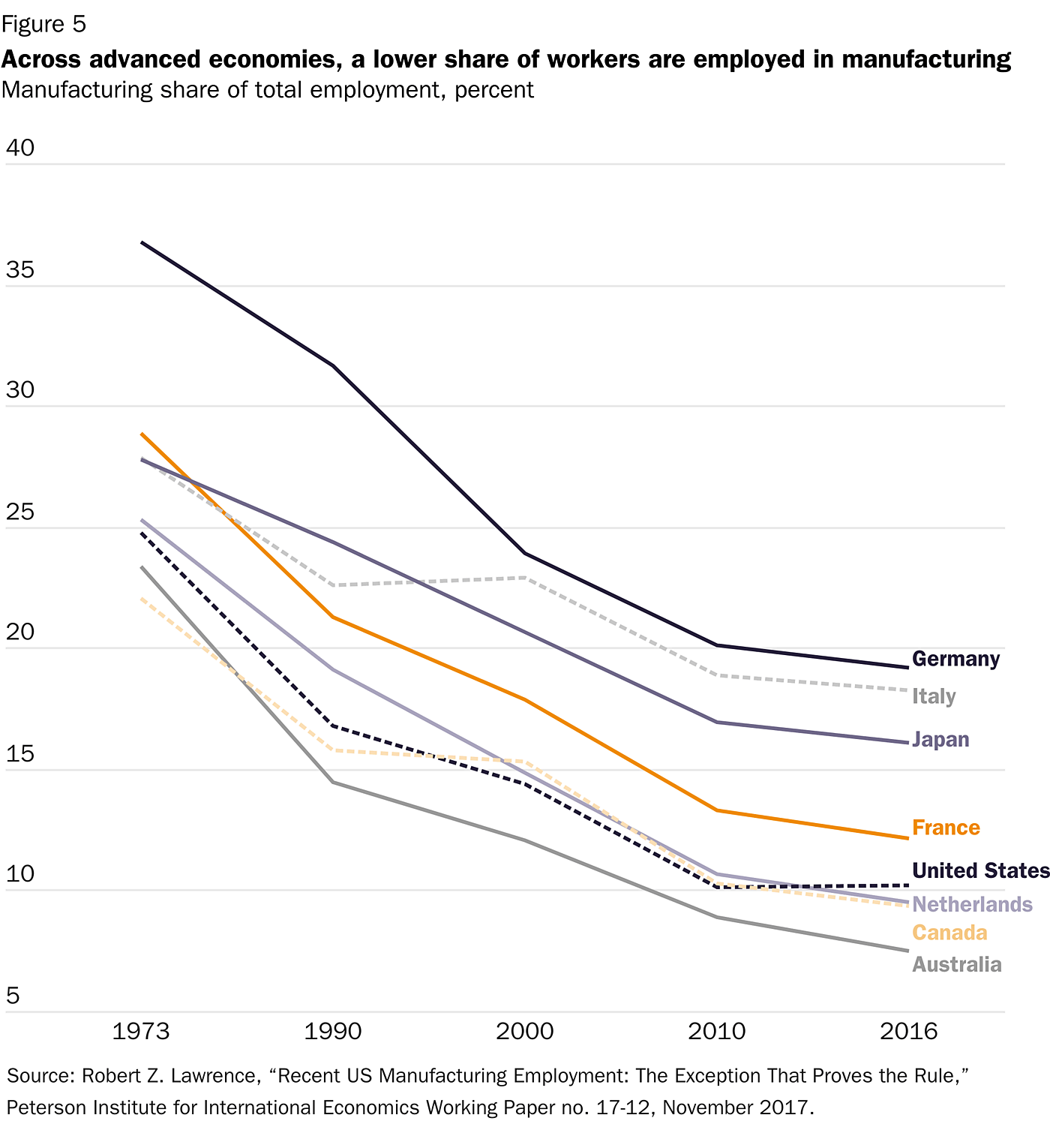

Further confirmation is provided by similar data from other advanced economies—including ones with persistent trade surpluses and active labor and industrial policies. Manufacturing’s share of employment nearly halved in Germany from 1973 to 2016 while Australia witnessed a two-thirds reduction over the same period. Manufacturing’s reduced share of employment isn’t particular to the United States but rather reflects a broader international phenomenon (Figure 5).

Noting this trend over 25 years ago, a 1997 International Monetary Fund paper described the trend away from manufacturing as “simply the natural outcome of successful economic development” and “generally associated with rising living standards.”

Manufacturing’s Relative Decline Also Reflects Shifting Consumption Patterns

Manufacturing’s declining share of employment and GDP can also be explained by shifting U.S. consumption patterns in favor of services over goods. In short, as Americans have become richer, more of their income—nearly twice as much—has been spent on services instead of stuff. This trend was underscored during the COVID-19 pandemic when, faced with greatly restricted entertainment, dining, and vacation options, Americans’ consumption of durable goods surged. A possible accelerant of this trend is that some traditionally manufactured products such as maps, notepads, compact discs, and DVDs have been “dematerialized” into streaming services or software applications.

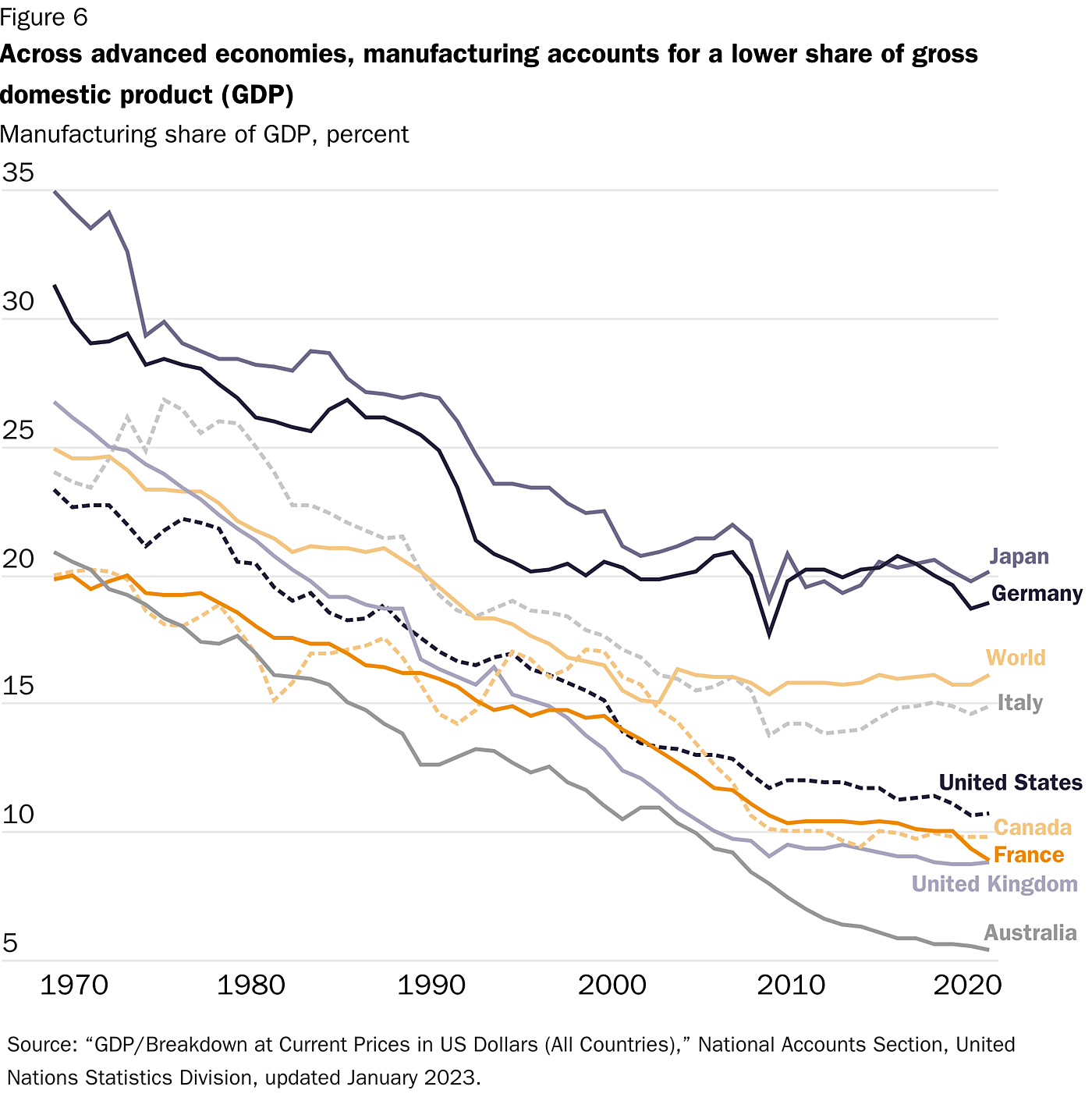

As with automation, the American experience has been replicated in other wealthy economies as well as global GDP as a whole where services account for a growing share of consumer spending and where manufacturing’s share of both GDP and employment has declined (Figure 6).

“Domestic Outsourcing” Plays a Large Role in Regional Declines

While countries such as China and Mexico are often blamed for the shift of factory work away from the Rust Belt, in many cases the relocation of such work has been not to other countries but to other states. From 2001 to 2018, for example, the South saw a 17 percent increase in the number of automotive manufacturing jobs while other regions experienced declines ranging from 21 to 47 percent.

A similar example can be found in the domestic steel industry, which has seen a shift away from large, integrated steel mills in favor of “mini-mills” that employ electric arc furnaces to melt steel scrap or direct reduced iron. While most integrated mills are in Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—Rust Belt states synonymous with industrial decline—many mini-mills are in the South. U.S. Steel, the country’s third-largest steel producer, offers an interesting example of this dynamic. In 2022, the company broke ground on a new advanced mini-mill plant in Arkansas while four months later, U.S. Steel announced it was in talks to end production at one of its older integrated steel mills in Illinois.

Broader data show the uneven geographic recovery in manufacturing employment since the Great Recession, with much of the gains from 2010 to 2017 concentrated in Mountain states along with the “auto alley” stretching from the Great Lakes down through Mississippi and Alabama. In contrast, New England and the Middle Atlantic states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York continued to lose manufacturing jobs during this period.

This pattern of U.S. firms decamping from northern latitudes to more economically hospitable climes farther south is a familiar one. The shift of textile production from New England to the South is a well-known example. As late as 1925, New England was home to 80 percent of the domestic textile industry but by 1954 accounted for only 20 percent as mill operations migrated south. Today the South remains home to numerous textile manufacturers, but such firms account for far less employment than in the past with production having shifted to highly automated facilities. A similar dynamic can be seen among furnituremakers. Domestic employment shifted to the South and then overseas, but several firms maintain a U.S. presence by emphasizing customization and niche markets.

Manufacturing Jobs Aren’t Necessarily Better Jobs

Concerns over the relative decline of manufacturing employment often reflects a sense that compensation in the sector is superior to that of services jobs. The United States, some may believe, is losing “good jobs” and replacing them with relatively low-paying ones (aka “McJobs”). More recent data, however, suggest otherwise.

First, not all manufacturing jobs are particularly well paid. In 2016, for example, production workers at U.S. sawmills received average hourly pay of $18.60 while the comparable figure in aircraft manufacturing was over $40 (for reference, the average hourly earnings for all private-sector employees in 2016 was approximately $25).

Perhaps more importantly, compensation levels for manufacturing jobs in some instances may be inferior when compared to jobs in other industries after controlling for various factors. As the Congressional Research Service observed in a 2018 report:

Contrary to the popular perception, production and nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing, on average, earn significantly less per hour than nonsupervisory workers in industries that do not employ large numbers of teenagers, that have average workweeks of similar length, and that have similar levels of worker education. For example, nonsupervisory workers in manufacturing earned an average hourly wage of $21.29 in 2017, compared with $26.73 for nonsupervisory construction workers and $36.21 for nonsupervisory workers in the electric utility industry.

A senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis pointed out that, while the average manufacturing worker earned $0.50 more per hour than the average private-sector worker in 2010, by 2022 the average manufacturing worker was earning $1.12 less. This finding comports with a 2019 Bureau of Labor Statistics report noting that in 1990, production workers in manufacturing had hourly earnings approximately 6 percent greater than those of production or nonsupervisory workers in the total private sector ($10.78 versus $10.20) but that by 2018, such workers were earning about 5 percent less ($21.54 versus $22.71). In addition, a 2022 paper found that the wage premium for manufacturing jobs has disappeared and noted that manufacturing wages rank in the bottom half of all jobs in the United States.

Such data perhaps explain manufacturers’ concerns over labor shortages that have been described as the sector’s greatest long-term obstacle to growth. Through most of 2021 and 2022, for example, the number of unfilled U.S. manufacturing jobs never dropped below 800,000, and it remained historically elevated in 2023 even as the industry struggled. Far from a lack of employment opportunities, the apparent greater threat to U.S. manufacturing prosperity is a lack of workers to fill such positions.

Beyond wages, there are also other reasons to discount the premium that is sometimes placed on manufacturing jobs. Research released by the International Monetary Fund in 2018, for example, found that manufacturing does not play a unique role in productivity growth and that “some service industries [exhibit] productivity growth rates as high as the top-performing manufacturing industries.”

In short, if reasons exist for U.S. policymakers to actively promote domestic manufacturing, jobs aren’t one of them.

The Role of Increased Trade and Global Economic Integration

While numerous factors including productivity gains, changes in consumer preferences, and geographic shifts in manufacturing activity within the United States explain the lion’s share of manufacturing’s decline in employment, trade plays a role as well. Factories located in other countries have a comparative advantage over those in the United States for certain manufacturing activities. But this shouldn’t provoke undue worry.

From a historical perspective, the dispersion of some manufacturing jobs to other countries since the 1950s was an inevitability. With much of Europe and Japan’s manufacturing reduced to rubble during World War II and much of the rest of the world forced into mistaken experiments with communism, the United States began the post-war era as the world’s preeminent manufacturing power almost by default. From that point, the trend could only be in one direction as other countries rebuilt and reemerged as manufacturing powers.

Rather than undermining U.S. prosperity, however, manufacturing’s spread allowed for greater specialization and trade that undergirded the post-war economic boom and rise in living standards. Outsourcing jobs abroad allowed for the creation of new and better compensated jobs within the United States. Driving down the cost of production through cheaper production overseas has allowed U.S. firms to lower prices and increase sales of their products, which in turn increases demand for better compensated jobs in areas such as design, market, and maintaining or servicing these products.

Although superficially worlds apart, there is little functional difference between manufacturing work being transferred to a worker in another country or to a robot or advanced machine on American soil. Both are properly understood as productivity drivers that lie at the root of prosperity. Through such productivity enhancements, the United States reduces the cost of producing goods and raises its standard of living.

The Value of Economic Diversity

Although U.S. manufacturing’s relatively reduced prominence and shift toward a more services-oriented economy has prompted worries, often overlooked are the benefits of such economic diversification. Germany, Taiwan, and South Korea, for example—all with economic fortunes significantly more tied to manufacturing output than the United States—have been hit hard in recent years amid supply chain problems and flagging demand for manufactured goods in overseas markets. With far more of their economic eggs in a single basket, such downturns are more painful than in economies that rely on numerous industries and sectors to serve as growth drivers.

A country with too much manufacturing or high trade barriers can, perhaps contrary to perceptions of strength associated with industrial might, be less resilient and more prone to pronounced downturns or economic shocks. Just as the United States should be wary of its manufacturing base disappearing (which has not happened!), it should also be cognizant of the downsides that come with an economy overly weighted toward factory output.

Dos and Don’ts for Boosting U.S. Manufacturing

While manufacturing remains a vibrant part of the U.S. economy, an optimized policy environment could help the sector retain its competitiveness and position it to meet current and future challenges. The following are policy recommendations to ensure that the United States remains an attractive location for manufacturing.

Don’t engage in industrial policy: Politicians and myriad other commentators regularly call for new measures designed to promote the fortunes of selected industries, but such proposals should be greeted with extreme skepticism. Despite professed clairvoyance by some observers about which industries are destined to become key drivers of future growth, the future is often hazy, and such public-sector-backed bets rarely pay off. Businesses and investors, guided by price signals and market feedback—as well as incentivized by the profit motive—are far better positioned to assess and identify opportunities for growth than politicians and bureaucrats beholden to political pressures.

Don’t impose new protectionist measures (and remove old ones): Protectionism seeks to bolster particular firms or industries by reducing or entirely removing competition by foreigners. Not only do such measures often fail to produce the desired effect—removing competition discourages the kind of innovation that helps keep firms competitive—but it also inflicts harm on the rest of the economy. Raising the price of steel through tariffs and quotas, for example, undermines the numerous domestic industries, such as automakers and construction, that rely on steel as an important input. Thus, the many current tariffs on imports of manufacturing inputs—which constitute around half of all U.S. imports—perversely harm most American manufacturers.

Do expand immigration: An important determinant of manufacturers’ success—as with all industries—is access to a talented and reliable workforce. Amid labor shortages, it is more important than ever that Congress reform the U.S. immigration system to ensure that U.S. manufacturing firms have access to the human capital needed to thrive. The National Association of Manufacturers has made this point in its advocacy for a streamlined immigration system.

Do reform the U.S. tax code: Manufacturing is a capital-intensive industry, but the U.S. tax code forces deductions for such expenses to be spread out over a number of years. By denying manufacturers the ability to fully recover their investments quickly, the tax code effectively raises the cost of capital investments due to inflation and the time value of money. To correct this, the tax code should be changed to allow for full, immediate expensing of capital investment.

Conclusion

Doom and gloom around the state of U.S. manufacturing is deeply misplaced with a variety of metrics showing the United States as one of the foremost players in this important sector. Annual production and exports of manufactured goods reach into the hundreds of billions of dollars and includes advanced products such as electrical machinery, aircraft, and medical equipment. That the sector employs fewer Americans and accounts for a lower percentage of economic activity than in years past is largely due to productivity gains and changes in consumer preferences in favor of services and fewer material goods. Rather than a harbinger of weakness, these shifts are consistent with those seen in other advanced economies. Furthermore, factory closures in some parts of the United States—including the so-called Rust Belt—reflect domestic rather than international shifts as production is transferred to U.S. locations deemed more efficient centers of manufacturing.

Nevertheless, there is scope for policy reforms to further bolster the fortunes of U.S. manufacturers, including the removal of tariffs and other impediments to the efficient sourcing of key inputs as well as expanded immigration to boost the human capital available to these firms. With such measures, the sector would be well positioned to remain a vital source of economic strength for many decades to come.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.