-

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, the world is not “de‐globalizing,” and the supposed “death of globalization” has been wildly oversold.

-

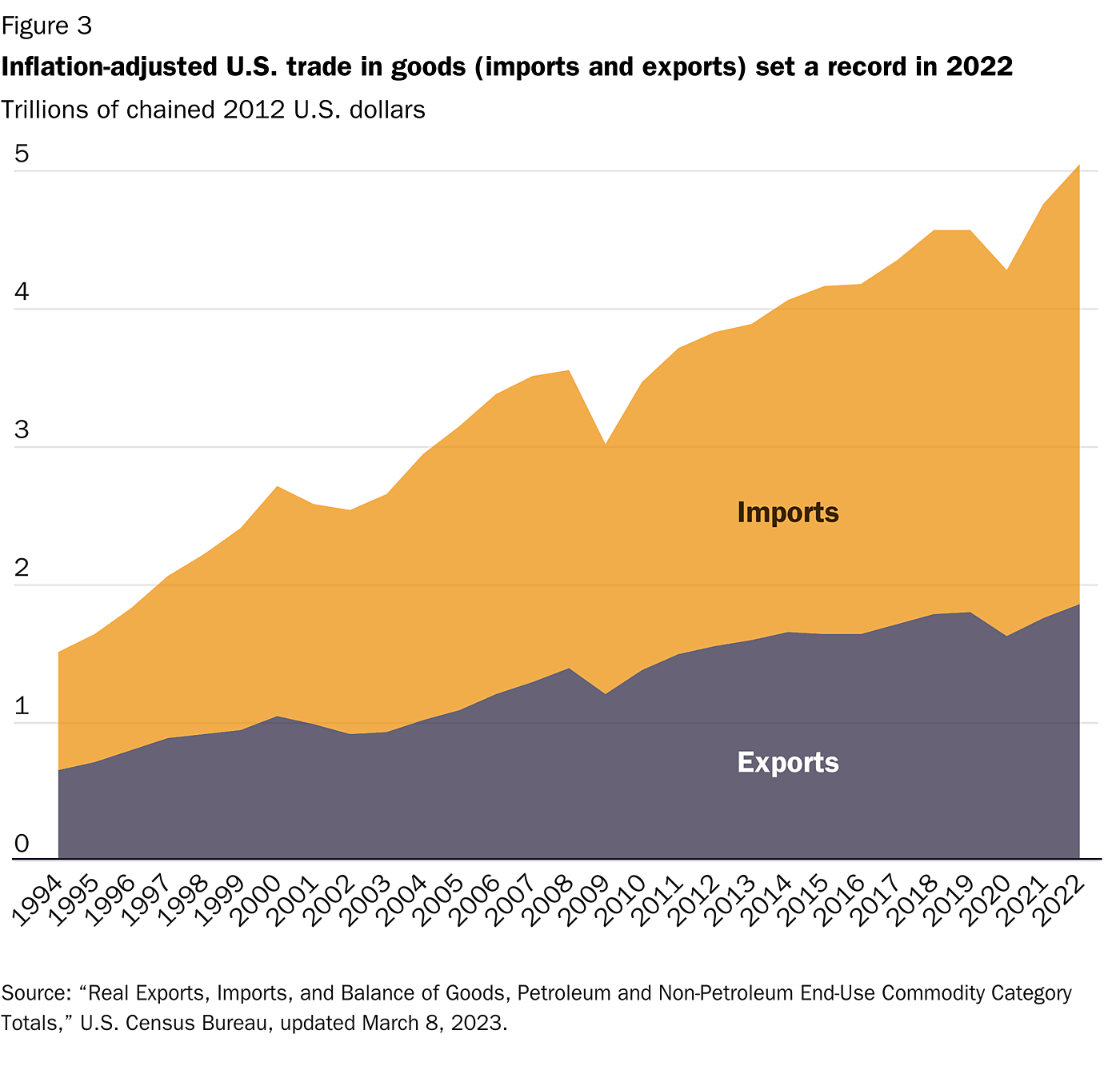

World trade in goods may have plateaued but did so at historically high levels, and some moderation was inevitable. In the United States, exports and imports of goods set inflation‐adjusted records in 2022.

-

Meanwhile, other indicia of globalization—trade in services, digital trade, cross‐border investment and migration, and cultural exchange—continue to increase.

-

Patterns of trade and global supply chains are surely evolving in light of new economic and geopolitical factors, but such changes are common. Instead of de‐globalizing, multinational corporations are mainly “re-globalizing”—diversifying sourcing, upgrading logistics technology, altering inventory strategies, etc.

-

Globalization might therefore be different from what we understood it to be a decade ago, but cross‐border trade, investment, and migration aren’t, in general, going anywhere—at least not yet. Given globalization’s myriad benefits, we should hope it stays that way.

The pandemic, Ukraine, simmering U.S.-China tensions, and rising American populism have led many politicians and pundits to boldly proclaim that a new era of de-globalization is upon us. Factories are “re-shoring,” economies are “decoupling,” and everyone has abandoned “neoliberal” free trade. Some have gone so far as to openly—and ominously—wonder whether we are witnessing the “end of globalization.”

Surely, the last few years have stressed the global economy and seen certain policymakers more pessimistic about foreign trade and investment than they’ve been in decades past. Nevertheless, the evidence thus far shows that globalization is not dying but instead evolving in response to various economic and geopolitical trends. In fact, one big problem with the current de-globalization chatter is that it misunderstands—sometimes wildly—what globalization actually is, as well as the rules that undergird it. It also ignores—as economist Jeffrey Kleintop has pointed out—the long history of people wrongly predicting globalization’s imminent demise. As this essay documents, today’s skeptics likely will be proven wrong once again.

What Does Plateauing Global Trade in Goods Really Say about Globalization?

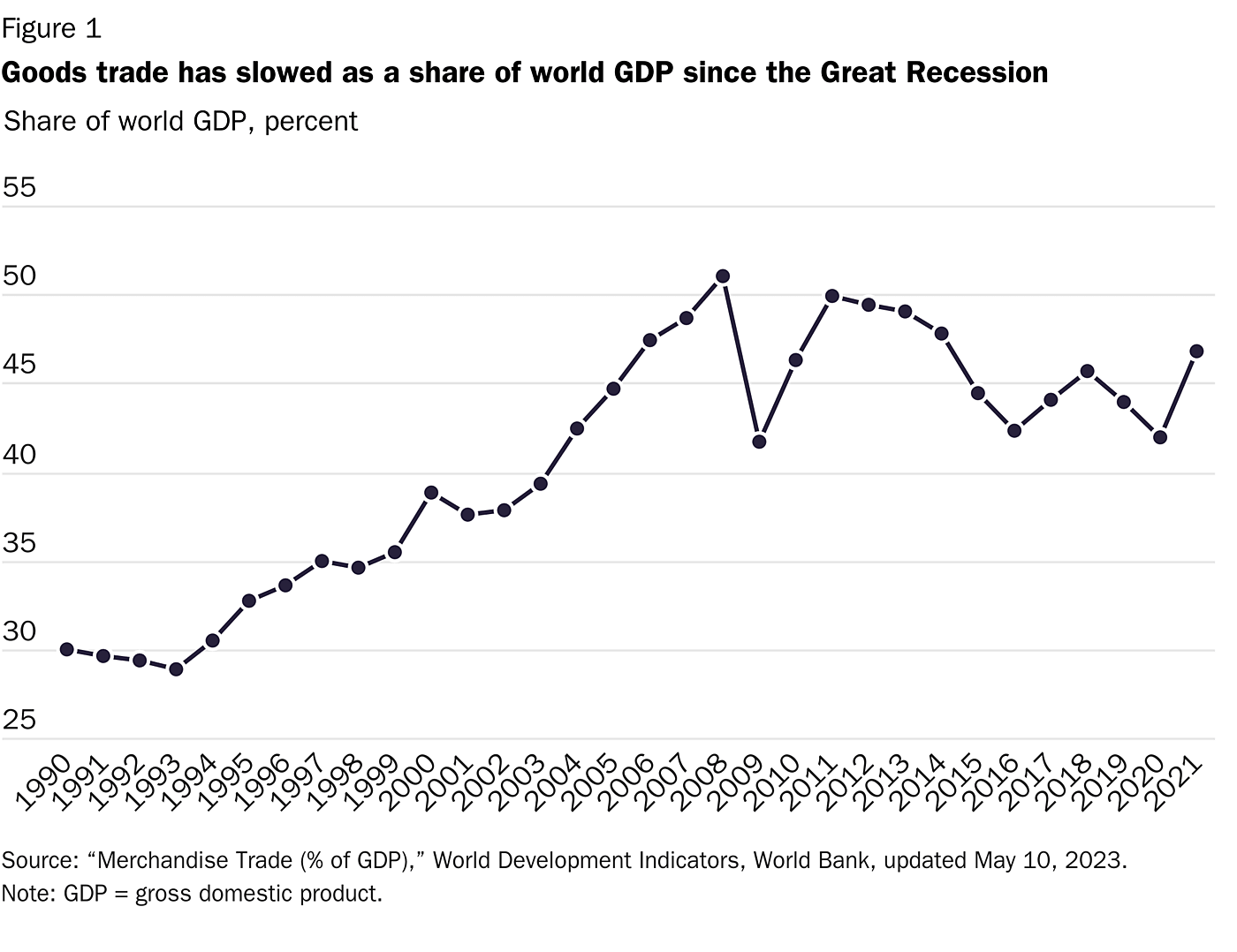

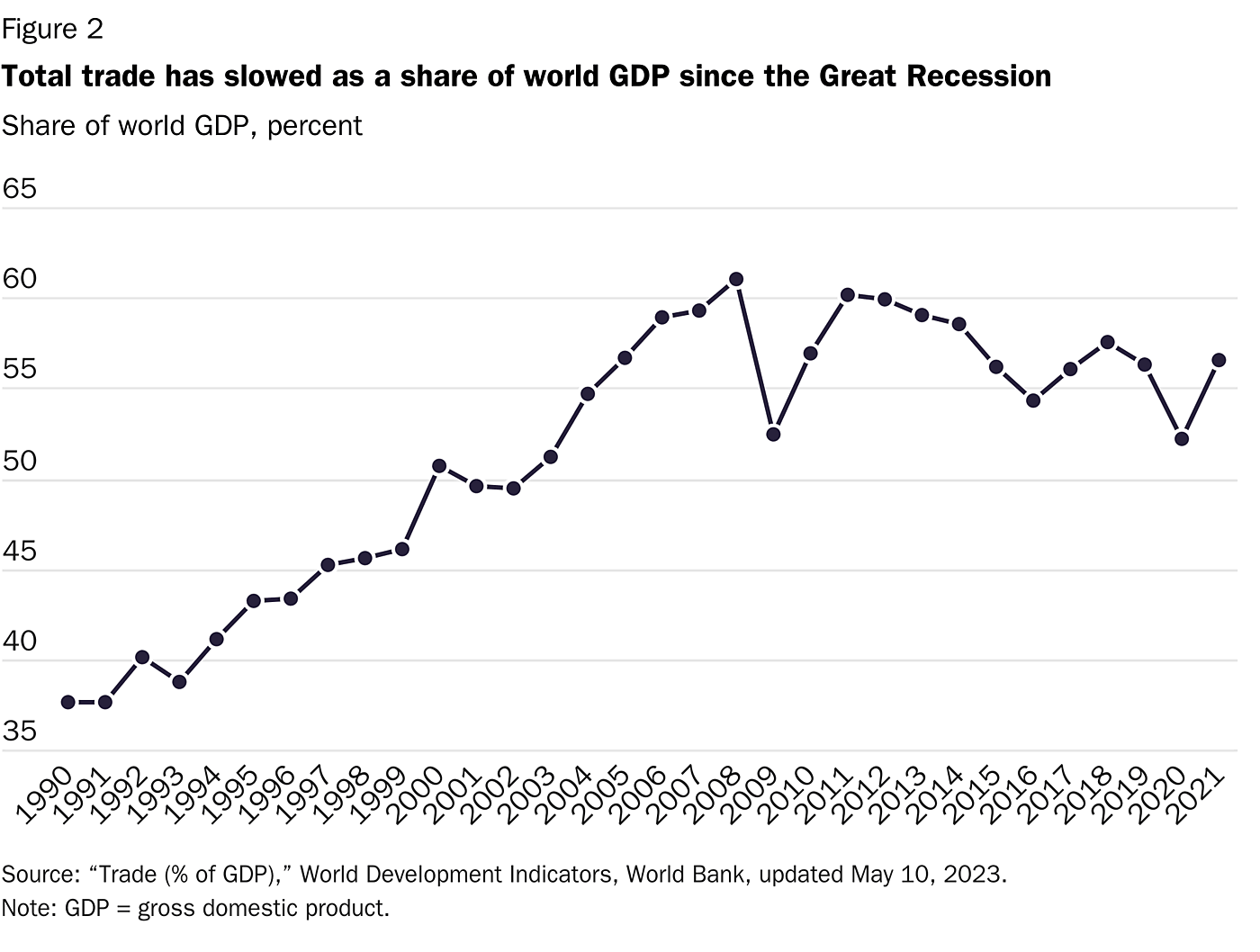

The primary datapoint used to announce the “death of globalization” is the slowing share of both goods trade and total trade as a percentage of global gross domestic product (GDP) since the Great Recession (see Figure 1 and Figure 2), with the former driving the latter because goods trade accounts for a large share of total trade. Given this relationship—as well as recent supply chain snarls and the centrality of goods, tariffs (which apply to goods), and containerized shipping to the typical story of globalization—some focus on trade in goods is understandable. Yet plateauing international trade in goods is not a very useful indicator of de-globalization.

First, goods trade as a share of global economic output may have peaked in 2008 at 51.1 percent but remained historically high in 2021 at 46.8 percent—well above levels seen during the “hyperglobalization” heyday of the 1990s and higher than it was in 2016 through 2020. Economist Richard Baldwin adds that most of the decline in goods trade since 2008 was due to two factors: (1) China returning to a normal level of trade and (2) a collapse in mining and fuels prices. Other economies, as well as trade in manufactures and agricultural goods, experienced no such collapses. Thus, these data at most reveal a period of stagnation (or “slowbalisation”) instead of a serious de-globalization retreat.

Second, there is little reason to think that goods trade should have continued previous decades’ upward trend; instead, several factors make eventual moderation inevitable. For example, practical constraints on shipping (e.g., on cost savings, capacity and speed, or specific product traits), evolving consumer tastes (e.g., for vine-ripe produce or quick access to customized items), and new technological developments (e.g., industrial robots that make high-wage countries more competitive) naturally push against the globalization of certain manufacturing supply chains and make local or nearby production more financially attractive.

Furthermore, some of this moderation reflects the fact that, as I explained in a 2020 Cato Institute paper, countries increasingly produce and consume services (and move away from goods) as they develop. Thus, as world manufacturing output and agriculture output decline as a share of global economic output over time (because nations are developing and thus shifting a greater share of their economic activity to services), it makes sense that goods trade as a share of that same global economic output stops increasing at the breakneck pace it exhibited in earlier periods—even as goods trade continued to increase in nominal, inflation-adjusted terms. Since many services—such as construction, maintenance and repair, or hospitality—are nontradable and many others face domestic regulatory barriers (e.g., occupational licensing), it would be difficult for services trade to offset a trade-in-goods moderation, at least in the near term.

Finally, there is ample evidence that global goods trade remains quite healthy, if not expanding, in many areas. In the supposedly retrenching United States, for example, inflation-adjusted merchandise trade (imports plus exports) reached record levels in 2022, with less than 12 percent of that total coming from petroleum products (see Figure 3).

According to the United Nations, moreover, 2022 global merchandise trade hit a record high in terms of both nominal value ($25 trillion) and volume. The DHL Global Connectedness Index 2022 report from the global logistics giant found much the same:

Trade in goods plummeted at the beginning of the pandemic, but after just three months of declines, trade volumes swiftly recovered to above pre-pandemic levels and continued growing through the early stages of the war in Ukraine. As of mid-2022, the volume of world trade in goods was 10% higher than it was at the end of 2019.

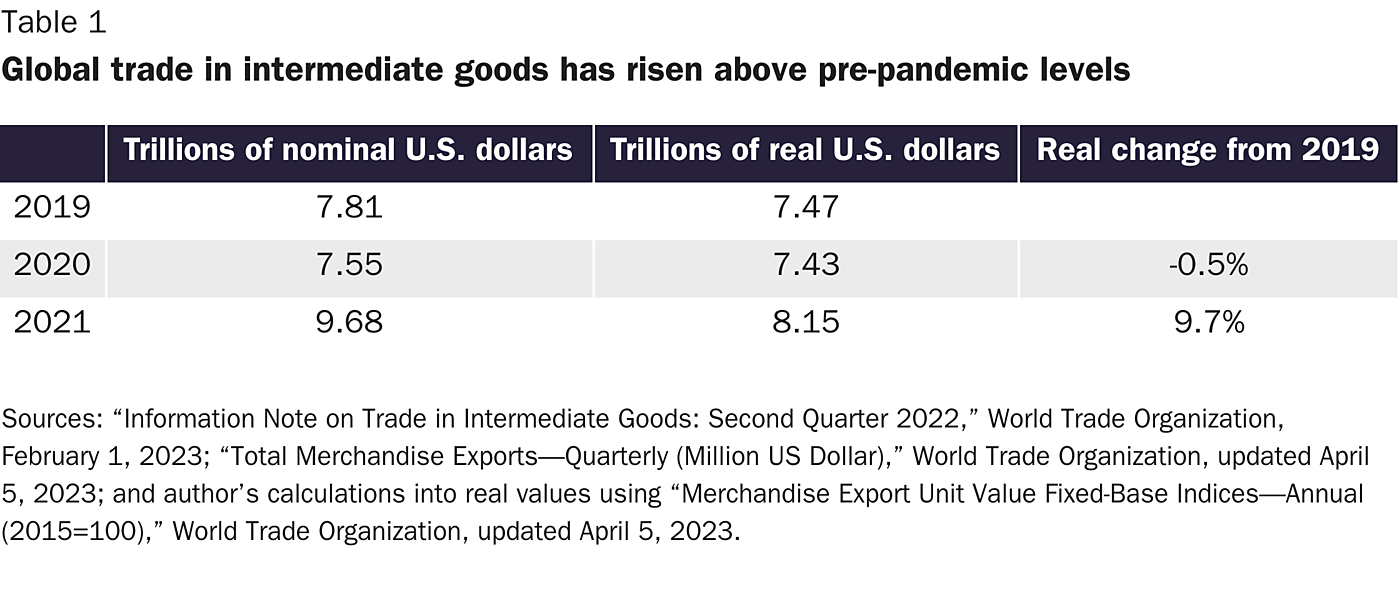

Finally, the latest data from the World Trade Organization (WTO) show that global trade in intermediate goods—items used to manufacture downstream products and thus a sign of companies’ use of global value chains—was well above pre-pandemic levels in 2021 (see Table 1) and heading for even greater heights in 2022.

Other indicators reveal similar strength for global trade in goods: For example, a record number of ships (23,583) transited the Suez Canal last year—easily surpassing a 2021 record (20,694) that occurred despite the famous Ever Given ship blocking the canal for several days. The Suez Canal Authority is expanding the canal to handle even more traffic in the years ahead. The Panama Canal also saw record tonnage in 2022 (beating 2021’s record), while U.S. ports broke volume records in 2021 (Los Angeles, Long Beach) and 2022 (New York/New Jersey, Houston, Virginia, Savannah, and Charleston).

In short, there are numerous signs that global goods trade is still increasing—just not as fast as the rest of the global economy. This is hardly the “death of globalization.”

What’s Going On with the Other Aspects of Globalization

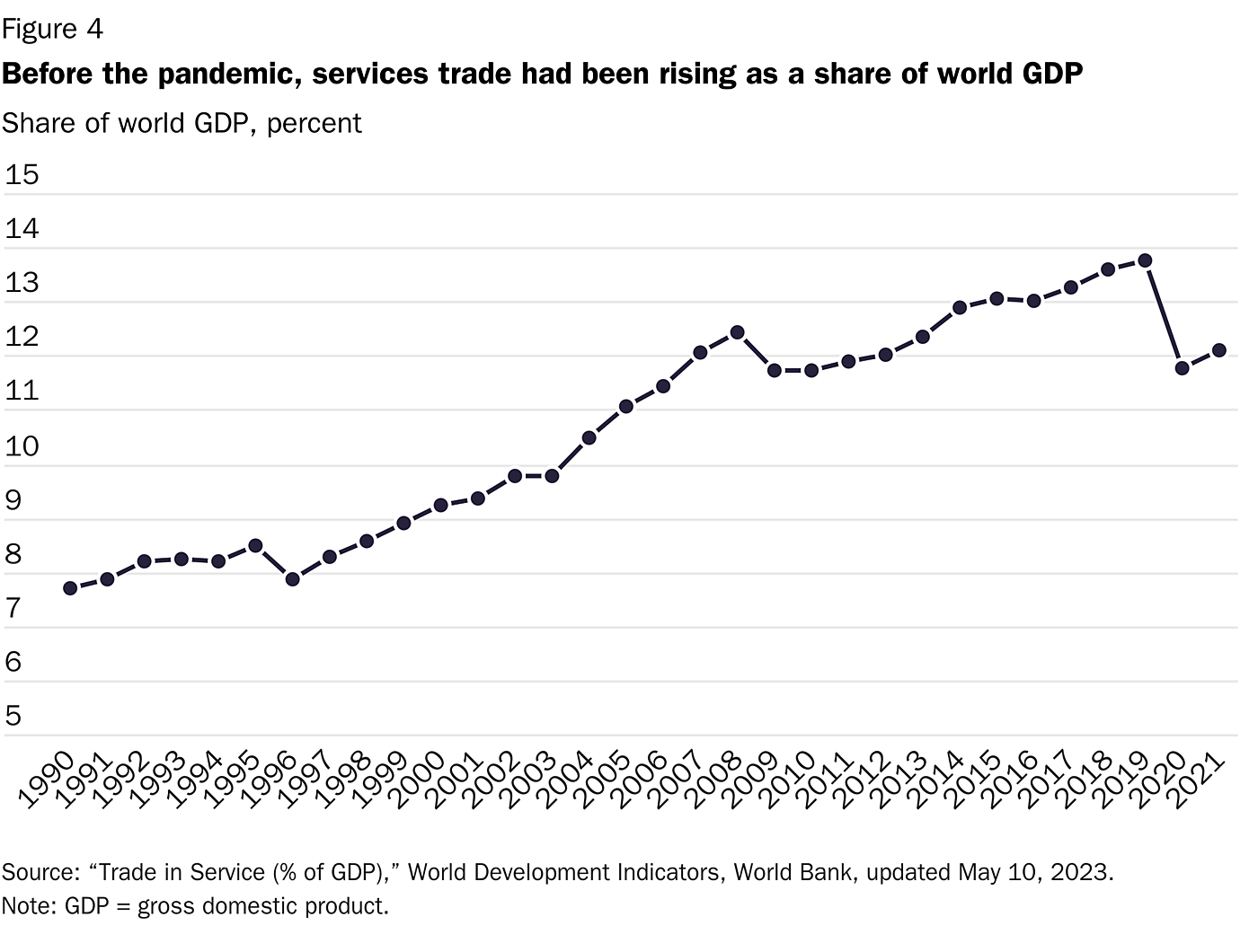

Just as importantly (if not more so), the many non-goods aspects of globalization show little signs of long-term stagnation. For starters, global trade in services was continuing to surge before the pandemic, which cratered all trade, even as goods trade (again, as a share of global GDP) had been sagging for years (see Figure 4).

Because global services trade has outpaced goods trade for about two decades now, commercial services’ share of total exports rose from 21.31 percent in 2005 to 24.82 percent in 2019. Particularly important was trade in computer services, research and development services, and health services, which have seen average annual growth in the double digits.

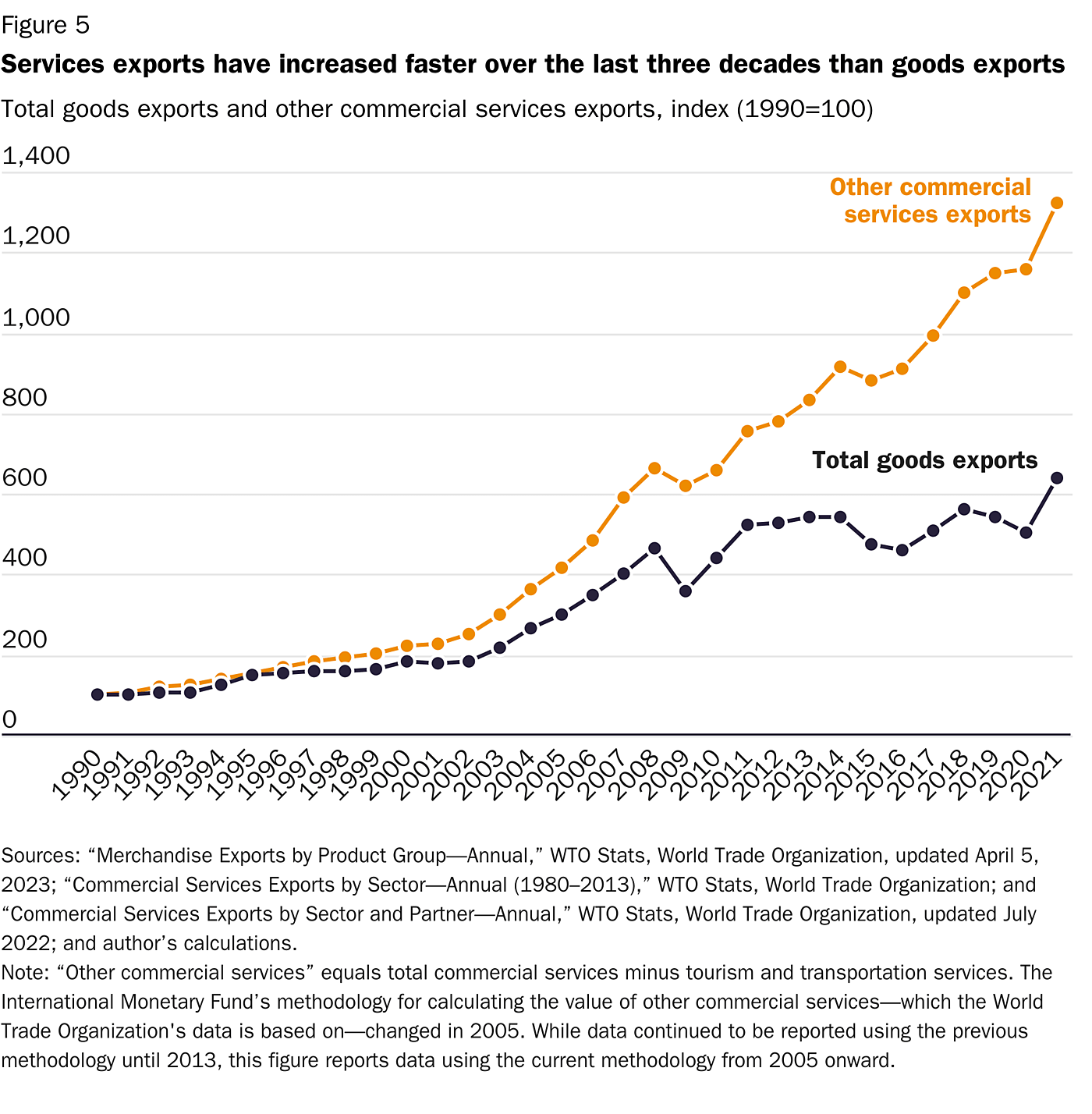

The pandemic, of course, crippled trade in many services that are dependent on travel (business and leisure), but many other services resumed their upward climb after economies reopened in 2021—and did so despite government barriers. According to the WTO, for example, computer services, audio-visual services, insurance and pension services, financial services, business services, and charges for use of intellectual property all increased in 2021 versus pre-pandemic 2019. Contrary to most transport and travel services, many of these service industries avoided large declines in 2020 due to “the widespread adoption of technologies allowing remote work.” And, as shown in Figure 5, the catchall category of “other commercial services,” which covers approximately 60 percent of all services trade, has seen its global export growth rapidly outpace that of goods.

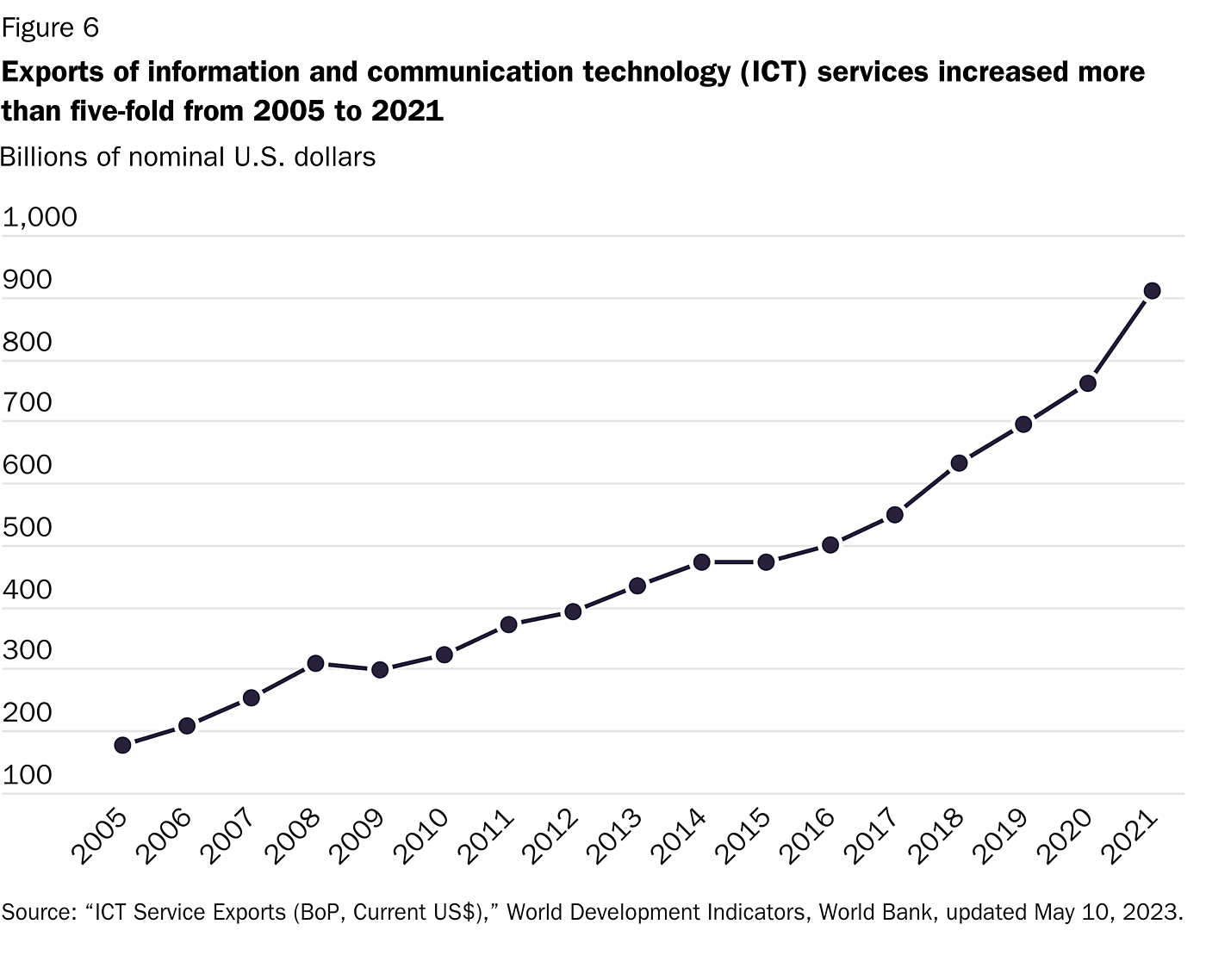

These data get to the hottest area of globalization today: digital trade, which includes the cross-border delivery and consumption of both information and communication technology products, such as software, and traditional services enabled by those same technologies, such as legal advice, research and development, or online education. According to the WTO, global exports of digitally delivered services more than tripled between 2005 and 2021, hitting $3.71 trillion that year (30 percent above 2019 levels). Information and communication technology services, meanwhile, have increased more than five-fold over the same 2005–2021 period (see Figure 6).

As noted, much of this digital trade is traditional services like law or accounting, but an increasing share is novel—what Middlebury College’s Gary Winslett calls “Peloton globalization”:

Not long ago, if a person somewhere in the United States wanted to take a spin class, they did so at a local gym or spin studio. That same person may continue to do so now, or they may get on an exercise bicycle at home, use the Peloton app, and be led through that class by instructor Ben Alldis coaching them from the Peloton studio in London. What was not so long ago a hyper-localized exchange of a service now takes place across international lines and is greatly facilitated by digitalization.

The growth of traditional and nontraditional digital services trade has significant implications for how we think about work, life, and “globalization” (emphasis added):

Two trends, international trade in services facilitated by greater digitalization and a shift toward more people working from home, are linked. Once a person is doing their professional work at home and delivering it digitally to whoever pays them, it doesn’t really matter whether that payer is domestic or international and so any dynamic that promotes work from home at least implicitly promotes the digital trade in services.… This is a newly emerging form of globalization that looks very different from ships carrying stacks of cargo containers but it is nonetheless a very real form of globalization. As a 2019 WTO report notes, “Globalization is not slowing or stalling. Rather, it is evolving, driven by trade in human skills, knowledge, and ingenuity.”

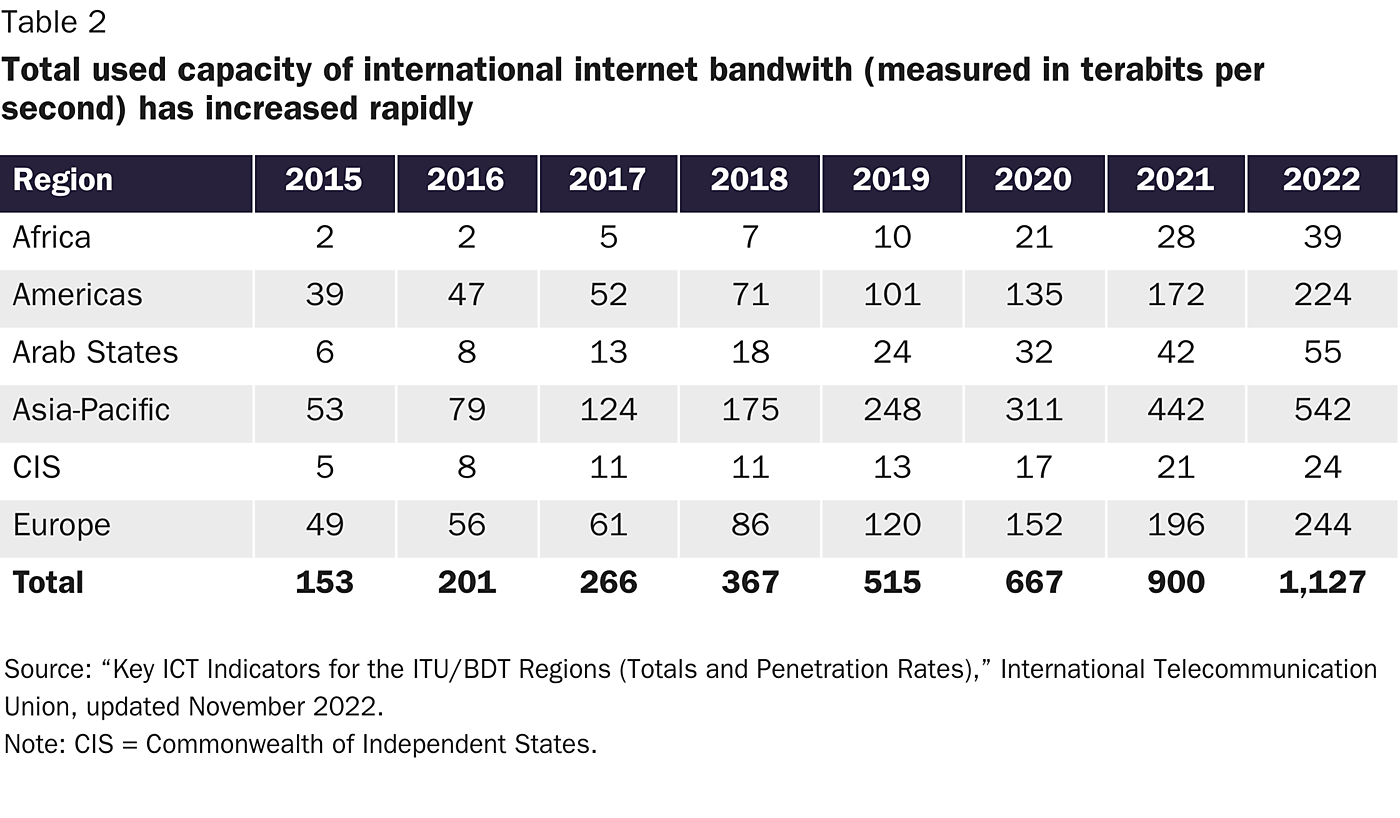

Data on digital trade flows confirm the trend—before and especially after the pandemic hit in 2020. According to the September 2021 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD’s) Digital Economy Report 2021, domestic and international internet protocol traffic in 2022 “will exceed all Internet traffic up to 2016,” and “monthly global data traffic is expected to surge from 230 exabytes in 2020 to 780 exabytes by 2026.” Measuring cross-border data flows is difficult, but the most commonly used measure—total used capacity of international internet bandwidth—has also seen remarkable increases in recent years (see Table 2), expanding more than seven-fold between 2015 (153 terabits/second) and 2022 (1127 terabits/second).

According to UNCTAD, cross-border data traffic is forecast to grow even more dramatically in the next few years.

Just as importantly, current estimates of worldwide digital trade are likely understated—and by significant amounts—because traditional trade statistics have difficulty capturing the origins, volume, and value of cross-border digital transactions. As Shawn Donnan at Bloomberg discussed in 2019 (emphasis added):

If we don’t always fully appreciate the scale of what’s going on, it’s because much of digital trade is not being captured in official statistics, says Susan Lund of the McKinsey Global Institute, the consultant’s in-house think tank. In a report, Lund and her co-authors documented an explosion in global data flows that they argued generated $2.8 trillion in economic output in 2014 alone and was doing more to benefit the world economy than the stalling international trade in physical goods.

In some cases, the World Trade Organization pointed out in a report last year, the rapid propagation of digital technologies has contributed to a false picture of globalization in retreat as shipping containers filled with hardcovers and DVDs are replaced by e‑book downloads and streaming music.

The article then cites specific examples of the types of cross-border digital transactions that conventional trade statistics miss and their potential impact on these oft-cited datapoints:

While Fortnite is notionally free to play, its maker booked billions of dollars in revenue last year from purchases of limited-edition “skins” and “battle packs” that allow players to customize their avatars. These types of transactions, however, are often not logged properly in economic data. If a player in China or Germany buys an outfit or weapon designed in North Carolina, he is effectively importing a digital good from the U.S. and helping to support a high-paying job in America.

There are less esoteric examples. Lund, for instance, cites the work of Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist: If the value of the Apple or Android operating systems loaded onto smartphones produced in China and other Asian hubs were counted as an American export to those countries, Varian argues, the U.S.’s $500 billion annual goods and services deficit would be reduced by $120 billion overnight.

Other hidden digital trade activities include “free” or inexpensive apps, “gig” consulting (especially when arranged by third-party platforms like Upwork or conducted via free videoconferencing and payment apps), the sharing economy (e.g., Airbnb), and streaming media—much of it generating additional economic activity that traditional trade data are probably undercounting or missing entirely. Cryptocurrencies undoubtedly add another layer of activity—and mystery—to the current digital trade world.

Given the remarkable increase in international bandwidth and cross-border data flows in recent years, the estimated $2.8 trillion in 2014 digital trade activity would surely be dwarfed by 2022’s total, which would itself be dwarfed by the total in eight more years. For perspective, consider the following back-of-napkin exercise: If digital trade activity experienced the same 739 percent increase that international bandwidth experienced between 2015 and 2022, then the true value digital trade would today approach $21 trillion—almost as large as worldwide trade in goods in 2021 ($22.4 trillion)!

In short, the data used to show de-globalization today probably underestimate actual cross-border trade and economic activity—and thus actual globalization—substantially.

Other aspects of globalization also show little reason for alarm. For example, the estimated number of international migrants increased from 153 million in 1990 (2.9 percent of the world’s population) to 281 million in 2020 (3.6 percent). And even in the face of the Great Recession and then the pandemic, global capital flows have continued flowing. The Economist reports, for example, that “in 2020 the stock of cross-border financial assets reached $130trn, an increase of almost 60% since 2007”; and at 153 percent of world GDP, these flows eclipsed their 2008 peak. The most recent UN report on global foreign direct investment, meanwhile, saw a 64 percent increase in foreign direct investment between 2020 and 2021 to $1.58 trillion, thus surpassing the totals in both 2018 and 2019. The latest foreign direct investment data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, moreover, show 2022 totals (through the third quarter) outstripping both 2021 and pre-pandemic levels.

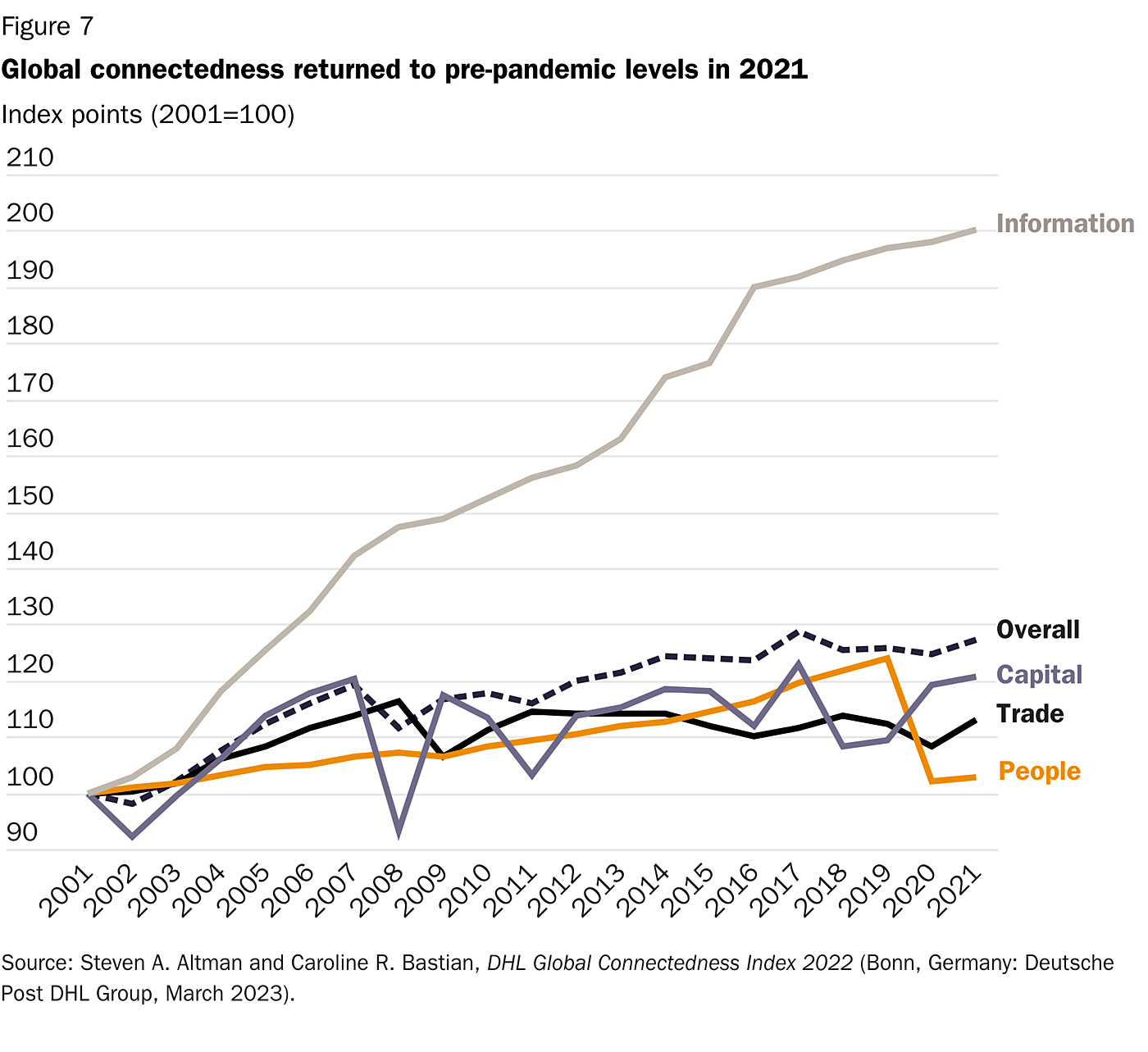

DHL’s Global Connectedness Index combines data on trade (goods and services), capital flows (foreign direct investment and equity), information (international bandwidth, telephone calls, scientific collaboration, and trade in printed works), and migration (tourists, students, and migrants) into a single snapshot of globalization. According to the latest report, the overall index in 2021 approached its all-time high (set in 2017) and likely increased even further in 2022, setting a record in the process (see Figure 7).

The report’s authors thus conclude (emphasis added):

The growth of international trade, capital, and information flows during the pandemic along with the recovery trend underway for people flows strongly rebut the notion that the Covid-19 pandemic or the war in Ukraine have caused a large shift from international to domestic activity. While some countries and regions are seeking to bolster domestic supply chains in selected industries, broad patterns of international activity clearly show that countries and companies have not retreated from international engagement.

Finally, our long-standing “cultural globalization”—food, art, etc.—continues apace. In music, Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny rose to fame writing and singing in Spanish and has been the most streamed artist on Spotify for three years running. Korean pop music boy-band BTS was in the Spotify’s top five and is regularly featured in U.S. commercials. High fashion has always been global, but “fast fashion” today also is featuring names like H&M (Sweden), Zara (Spain), Uniqlo (Japan), and Shein (China).

“Ethnic” cuisines, meanwhile, are so commonplace that American grocers are struggling to fit them all in the “ethnic food” aisle, where buyers and sellers prefer them. Meanwhile, “H Mart, a Korean American supermarket chain, has become one of the fastest-growing retailers by specializing in foods from around the world.” According to a 2015 survey, 80 percent of Americans “eat at least one ethnic cuisine each month,” and 66 percent “eat a wider variety of cuisines than they did [in 2010]”—totals that are surely higher today. The most popular fast-food restaurant in China, on the other hand, has long been KFC.

Most telling of all, however, may be U.S. streaming media giant Netflix. Of the American company’s 200-plus million subscribers, less than half (around 73 million) are in the United States and Canada. Netflix also streams and produces numerous “foreign” (non‑U.S.) shows and movies, and several of the most-watched Netflix shows—including Squid Game at number one—are in languages other than English. Lucas Shaw and Yasufumi Saito at Bloomberg add, “People actually spend more time watching foreign-language TV in the [Netflix] top 10 than shows in English.” And even American viewers are increasingly bingeing on foreign-language content. In 2020, for example, U.S. viewership of foreign-language titles grew by more than 50 percent, and Squid Game—a Korean show dubbed in English—dominated 2021. In 2023, Netflix’s German-language adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front received nine Academy Award nominations, winning four of them.

The confluence of these global cultural trends produces mind-bending stories almost daily. For example, Bloomberg reported in 2023 that American and Asian “influencers” on the Chinese app TikTok have—along with the “global boom of Korea’s entertainment industry”—fueled a Taiwanese “bubble tea” craze in the United States and thus surges in both U.S. bubble tea shops (many owned by Taiwanese companies) and imports of tapioca starch (“boba”) from Taiwan, Thailand, China, and Brazil.

American politicians might be souring on globalization, but American consumers most definitely are not.

Are Governments Abandoning Globalization?

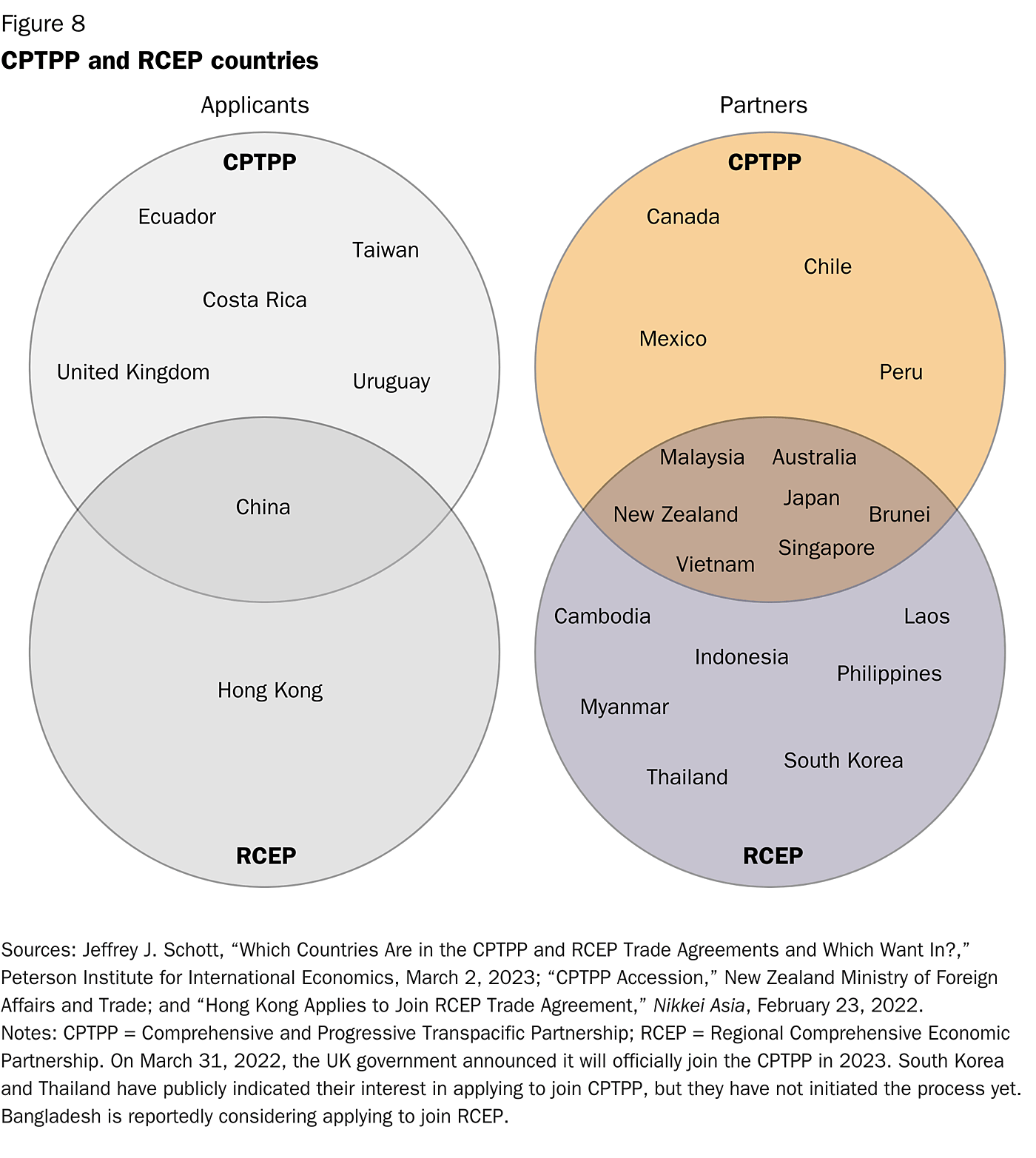

Politicians outside the United States aren’t turning their backs on globalization either. For example, the last few years have seen the completion of the large Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, formerly the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which the United States led and then abandoned) and the even-larger, but less ambitious, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, headlined by China (see Figure 8).

In Africa, meanwhile, the 54-nation African Continental Free Trade Area took effect in January 2021 and is in force for 43 signatories, making it the world’s largest new free trade area since 1994. While that agreement’s liberalization is relatively limited, the more comprehensive East African Community welcomed its seventh member (the Democratic Republic of Congo) in 2022, thus “bringing the regional trading bloc’s market size to a quarter of the continent’s population and providing it with access to the Atlantic Ocean.”

The European Union has concluded trade agreements with dozens of nations, several in the last few years, and is actively negotiating new deals with Australia, China, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines (though some of these are more advanced than others). European external trade (goods and services, imports and exports, excluding intra-EU trade), meanwhile, has increased dramatically from 18 percent of GDP in 1980 to 33 percent in 2016 to 43 percent in 2021.

Even traditionally trade-skeptic nations are signing trade agreements. Notoriously difficult India, for example, implemented an interim free trade agreement with Australia in December 2022, began negotiations on a more comprehensive arrangement in 2023, and—as previously noted—restarted talks with the European Union in 2022. China is negotiating eight new free trade agreements to supplement the 17 agreements it already has in force. The United States abandoned the Trans‐Pacific Partnership (TPP)/CPTPP in 2017 but then signed the U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) agreement with TPP parties Canada and Mexico, adding a few protectionist provisions but generally keeping the broad trade liberalization of the North American Free Trade Agreement and exceeding the TPP’s liberalization on digital trade. The Trump administration also signed a modest tariff liberalization deal with TPP signatory Japan and started other trade negotiations with Kenya and the United Kingdom, which post-Brexit has scrambled to sign alternative free trade agreements around the world and will officially join the CPTPP in 2023.

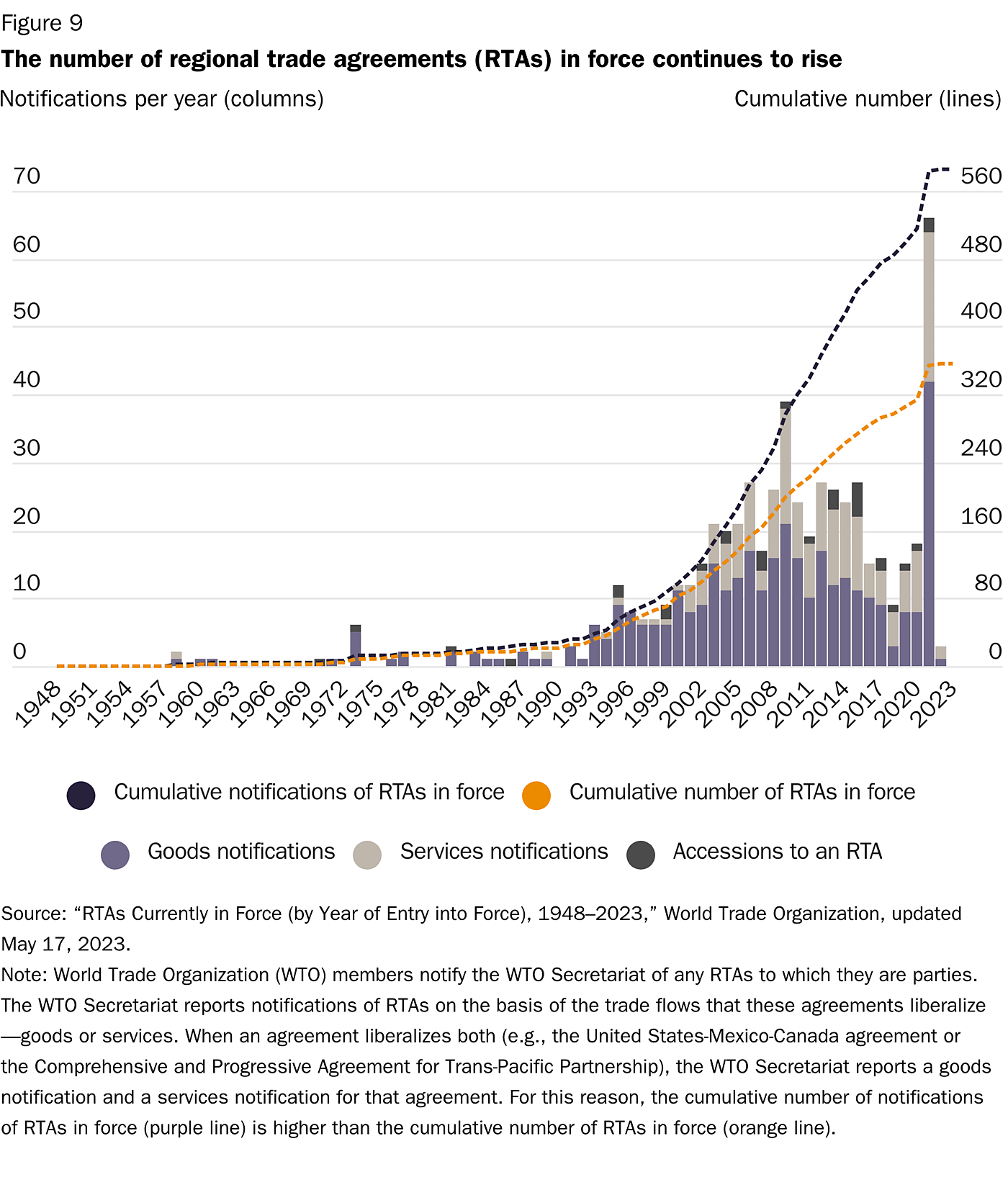

Overall, cumulative data from the WTO show that regional trade agreements continue to proliferate, with 356 in force as of the end of 2022 and—importantly—no clear sign of a forthcoming reversal (see Figure 9).

The WTO, on the other hand, has indeed suffered setbacks, beginning in 2011 with the official failure of the comprehensive Doha Round of multilateral negotiations and most recently enduring the United States’ February 2023 refusal to accept adverse WTO panel rulings on supposed “national security” tariffs. However, WTO rules—and their many exceptions—continue to serve as a baseline for the vast majority of global trade (basically everything except nonmembers Iran, North Korea, and few small others), and members have completed two small multilateral agreements on trade facilitation (2017) and fisheries subsidies (2022). Thus, WTO members’ deviation from the agreements’ baseline nondiscrimination and liberalization principles reflects less a wholescale abandonment of the multilateral system and more an incremental uptick in political disagreements with its specific terms and conditions. Surely, the organization needs reform and a new approach to trade negotiations, but both have been needed for two decades, and nothing since 2020 indicates that the system is collapsing entirely.

If Not De-Globalizing, What Are Supply Chains Doing?

The pandemic and Russia have surely caused multinational corporations to rethink their supply chains, but this trend has thus far been a story of re-globalization, not de-globalization. U.S. companies, for example, shifted some operations out of China but mainly to Southeast Asia or Mexico, not back home. (Mexico’s 13 free trade agreements with 50 different countries have surely helped this process.) These and other firms also diversified their inbound shipments away from West Coast ports to protect against possible labor unrest or other problems.

Declines in Russian or Ukrainian commodities, meanwhile, pushed international buyers to turn not inward but to Canada, South Africa, Latin America, the United States, India, and elsewhere. Inventory, sourcing, and related systems have also been overhauled (less “just-in-time” and more “just-in-case”), and the market has boomed for supply chain and logistics technologies that let multinationals better track shipments and processes. Thanks to these corporate efforts and moderating demand, early 2023 saw U.S. ports mostly clear, global shipping costs back to pre-pandemic levels, remaining supply chain problems manageable, and multinational manufacturers “better prepared for future supply chain snags.”

Even much-ballyhooed “nearshoring” and “friendshoring” efforts—pushes by companies and politicians to move supply chains to allied countries closer to home—may have been oversold. DHL found, for example, that “the general pattern since 2001 has been for international flows to take place over longer distances, indicating a smaller proportion of flows happening within regions.” While a large portion of trade has always occurred regionally, moreover, the average distance of global trade flows has actually gotten longer, not shorter, in recent years. It hit a record 5,100 kilometers in 2021. The authors therefore conclude that “there is no robust evidence of a rising trend in levels of regionalization through 2021,” though they acknowledge that more regionalization might occur in the years ahead.

Still, that shift would not be an abandonment of trade; it would be simply trade in a different form. Globalization skeptics missed this nuance because they misunderstood “globalization” as an immutable, straight-line series of trade flows and transactions instead of what it actually is: a constantly changing web of individual, mostly private actors doing business daily across national borders. In reality, multinational corporations and investors are always balancing numerous factors—costs, quality, transportation, storage, domestic and global political risk, and so on—and adapting when those factors change (which they regularly do). Since foreign “supply shocks” are as old as internationalized production itself and more common than often assumed, seasoned professionals did not simply abandon global trade when the COVID-19 and Ukraine shocks hit. They adjusted. One Brookings Institution study thus found that “global trade was remarkably resilient during the pandemic”—not simply because of friendshoring but because “non-friendly countries alleviated rather than caused critical bottlenecks.”

In sum, even after two massive, consecutive, and worldwide economic shocks, global business today is still very much global. It is just different from what it was a few years ago. And it will be different again in a few more.

Conclusion

The de-globalization narrative errs on what globalization actually is, on what global trade agreement rules say, and on what governments (via unilateral policy and trade agreements) and multinational companies are actually doing in response to recent disruptions. In the face of two major global shocks in less than three years, there is little sign that globalization, properly understood, is dying. Challenges surely remain—especially for the WTO and those hoping to see the U.S. government emerge from its self-defeating protectionist moment. But these rocks on our shores have once again proven incapable of stopping the ocean of globalization, whose waves are driven not by governments but by the actions of billions of private actors still eager to engage in peaceful, mutually beneficial commerce with little regard for political rhetoric or national borders.

At the start of the pandemic when store shelves were empty and uncertainty reigned, it was reasonable to wonder how the global trading system and supply chains would react. Three years later, however, the de-globalizers have no such excuse.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.