-

James Madison viewed tariffs as necessary to raise revenue but was caught off-guard by early attempts to enact tariffs for industry protection.

-

Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay supported the use of tariffs to stimulate infant industries. However, there’s little evidence the American System of tariffs and industrial subsidies was responsible for American economic growth in the 19th century.

-

Contrary to the “national conservative” narrative, many of the leading figures of the American Founding opposed the protectionist arguments of Hamilton and Clay.

-

From 1789 to 1934, tariff-seeking industries were notorious for diverting resources into rent-seeking, or the lobbying of Congress for preferential rates with bribes and backroom deals.

-

Corruption associated with protectionist tariff policy of the late 19th century directly led to adoption of the 16th Amendment and the federal income tax as an alternative revenue system.

-

Modern American trade policy was restructured in 1934 to bypass the disastrous Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which exacerbated the Great Depression and illustrated the tendency of protectionist tariffs to serve corrupt interest groups.

“For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world”

—Indictment of King George III, Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

Economists from across the political spectrum have long agreed on one area of policy: the removal of barriers to international trade. This consensus has guided the global embrace of trade liberalization between World War II and the present, coinciding with historically unprecedented levels of economic growth.

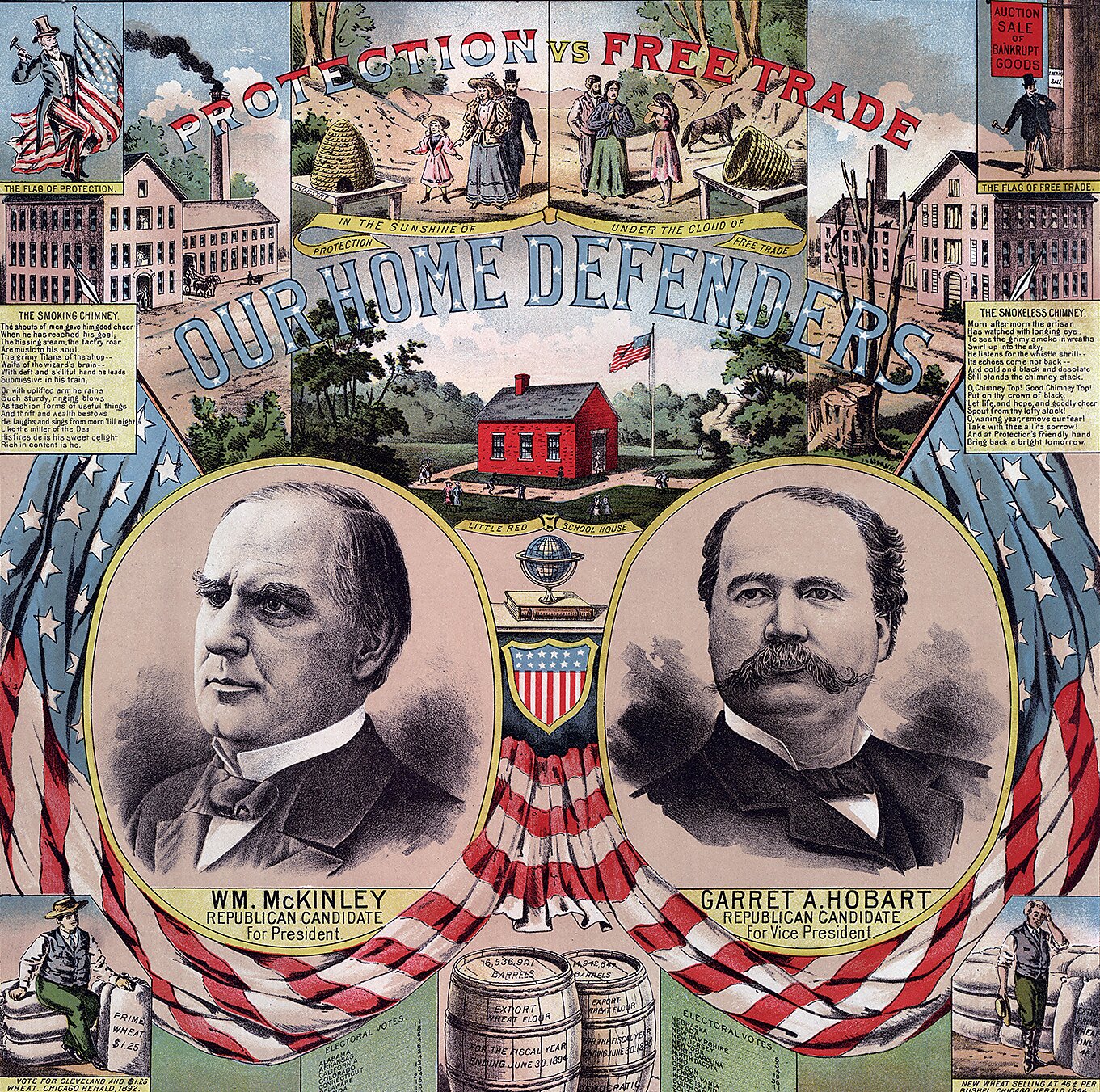

In recent years, free trade has gained numerous detractors who denounce the post-war period as an aberration from an alternative American economic history. From Pat Buchanan in the early 1990s to former U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer today, the United States became an economic powerhouse by strategically cultivating an industrial base through a system of protectionist tariffs, infrastructure improvements, and subsidies—the American System of the 19th century developed by politician Henry Clay. Proponents of this view often depict free trade as a foreign doctrine originating in Britain and present themselves as revivalists of a lost historical record in which the United States industrialized under the active encouragement of government policies.

National conservatives extend their historical account to the present, calling for the use of tariff-based protectionism to reverse the United States’ trade deficit between imports and exports. Their reasoning mistakes an accounting tool for a prescriptive policy while further neglecting that import restrictions impose symmetrical harms on exporters. They nonetheless propose leveraging tariffs and other restrictive measures against allegedly unfair foreign actors. China has now taken the place of Britain, yet as the national conservative narrative makes abundantly clear, it is the precursors of the American System where they find their inspiration.

While Clay undoubtedly gave rise to a protectionist or “neo-mercantilist” strain of economic arguments in the United States, his position was heavily contested from the moment he announced it on the Senate floor in 1824. Protectionism certainly aided beneficiary industries, but it also spread the burden of higher prices to consumers at large and to the political system through widespread public corruption. Contrary to national conservatives’ claims, the empirical link between tariffs and 19th-century economic development is weak—a case of post hoc ergo propter hoc reasoning augmented by bad statistics and tendentious historical narratives. Their account also overlooks the numerous instances in which tariff protectionism fomented diplomatic and constitutional crises, triggered international retaliation, and hindered American economic development.

This essay investigates the historical development of tariff policy between the Founding era and the end of World War II. These events illustrate a multi-century contest between protection and free trade, culminating in the disastrous Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 and instigating a shift in tariff-setting authority from Congress to the executive branch. The United States abandoned the American System approach with good reason after it produced a global economic quagmire at the outset of the Great Depression, and present trade policy is still conducted under the shadows of that mistake.

Prelude to American Trade Policy

The pursuit of free trade as national policy in the United States predates the Constitution. Responding to a Spanish government inquiry in 1780, John Jay expressed the fledgling nation’s commitment to a principle of unimpeded exchange: “every man being then at liberty, by the law, to cultivate the earth as he pleased, to raise what he pleased, to manufacture as he pleased, and to sell the produce of his labor to whom he pleased, and for the best prices, without any duties or impositions whatsoever.” Jay’s sentiments captured the Founding generation’s unease with Britain’s habit of manipulating its colonies’ trading patterns through political interventions—a stated grievance of the Declaration of Independence some four years prior.

At the same time, tariffs were far from foreign in the Founding era. Owing to their relative ease of collection, they provided a source of tax revenue. The drafters of the Constitution envisioned this role when establishing the “Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.” James Madison’s notes from the convention reflect the primacy of this purpose, noting that the “reiterated and elaborate efforts of Cong. to procure from the States a more adequate power to raise the means of payment had failed.” His comments alluded to the failed attempts of the Confederation Congress to establish a low and uniform “impost” of 5 percent on imported goods in 1781 and 1783.

The 1787 Constitution aimed to rectify this obstacle with a system of indirect revenue tools. As convention delegates explained, imposts included a category of taxes that “are appropriated to commerce” whereas domestic goods could be taxed by excises against their value, or by specific “duties” such as a stamp on paper goods. The document further restricted tax power by stipulating that “No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census.” This second clause effectively removed direct taxation from the table, as enacting a levy on property or income would trigger a cumbersome apportionment formula based on the population of the taxed person’s state. To raise revenue, the new federal government would either need to tax domestic production or international trade.

The new nation’s first foray into tariff policy began innocently enough on April 9, 1789, when Madison introduced a bill to the House of Representatives proposing specific duties on alcohol and applying a tax “on all other articles ___ per cent. on their value at the time and place of import.” Most expected a short debate, as indicated by Rep. Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, who followed Madison in suggesting “that the blanks be filled up in the manner they were recommended to be charged by Congress in 1783.” Rep. Thomas Fitzsimmons of Pennsylvania derailed the plan with a hastily drawn amendment to “encourage the productions of our country, and protect our infant manufactures.” The proposal caught Madison, and most of Congress, off guard. “If the duties should be raised too high,” Madison warned in a letter, “the error will proceed as much from the popular ardor to throw the burden of revenue on trade as from the premature policy of stimulating manufactures.” And yet the allure of specialized rates swept through Congress, prompting requests from a succession of amendments seeking differentiated rates for favored goods from their home district or state. In his first major congressional action, Madison had unwittingly awakened the very same brand of factional politics he so eloquently diagnosed in The Federalist Papers. Except for slavery, tariffs became the most contentious federal policy issue of the 19th century and remained a source of continuous discord until the Great Depression.

Tariffs under the early constitutional system differed substantially from their use today. As Madison’s 1798 bill illustrated, they were bound by the competing political objectives of revenue and protection. The government needed revenue, and tariffs on imported goods provided the lion’s share for the next 125 years. This required a stable stream of goods crossing the border, with a modest tax attached to each. However, a strategy of protection only works if it discourages consumers from buying foreign goods by raising the price through a tax levy. The aim is to induce consumers to purchase American-made products at a higher price—but at the direct expense of revenue, because tariffs cause imports to decline under the weight of taxation. If Congress catered too heavily to infant industries, the government could unintentionally undermine its own tax base. Most tariff schedules in the following century accordingly strove to balance (a) maximizing revenue under low impost-style rates on heavily imported goods and (b) affording “incidental” protection to specific industries through differentiated rates.

Formalizing Protectionism

Among the major figures of America’s Founding, Alexander Hamilton stands alone for his dogged espousal of trade restrictions. As early as 1774, he suggested the colonies could adopt a policy of self-sufficient autarky:

Those hands which may be deprived of business by the cessation of commerce, may be occupied in various kinds of manufactures and other internal improvements. If, by the necessity of the thing, manufactures should once be established, and take root among us, they will pave the way still more to the future grandeur and glory of America; and, by lessening its need of external commerce, will render it still securer against the encroachments of tyranny.

Hamilton maintained in 1782 that “preserv[ing] the balance of trade in favor of a nation ought to be a leading aim of its policy” and continued to espouse a theoretical case for protectionism for most of his life. His most famous foray into trade theorizing was an elaborate articulation of the “infant industry” argument in his 1791 Report on Manufactures. Alluding to Britain’s adoption of restrictive commerce and navigation policies against its colonies, the secretary of the treasury argued that considerations of fairness and self-sufficiency trumped theoretical ideals of free and open commerce with the world. Despite the rhetorical allure of his arguments, Hamilton also softened his specific policy prescriptions in the report. He proposed differentiated tariff rates, but they were only modestly protective in order to sustain a stable stream of revenue.

Hamilton’s more sweeping prescription—a system of bounties to support industries and infrastructure—failed to gain acceptance in his lifetime. In no small irony given his origins, he spent his final years pushing for restrictions on immigration, believing that they tilted the electorate to his great rival Thomas Jefferson. At the time of his death in a duel in 1804, the former secretary of the treasury left a more ambiguous tariff legacy than his later claimants acknowledge. In rhetoric, he laid out the arguments for heavy protection. In practice, though, he settled for the political realities and revenue needs of the government, acquiescing to a relatively moderate tariff schedule.

The case for high tariff protectionism in the United States fell to the next generation of political figures. The War of 1812 and its preceding embargoes on British goods unintentionally imposed a degree of industrial self-sufficiency on the fledgling nation. With the resumption of peace in 1816, former tariff detractors, including President Madison, acquiesced to higher rates that sustained some “incidental” protection to the same industries. The watershed moment for high protection came in 1824 in a speech by Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky. Alluding to the boon to industry during and after the war, Clay outlined the tenets of the American System and aggressively called for a national policy of high tariff protection, “internal improvements” to infrastructure, and a robust national bank to sustain federal expenditures through debt finance where necessary.

Clay’s speech remains central to the tariff mythology of today’s national conservatives, as it allegedly fostered a centurylong protectionist consensus in the United States. This version of history ignores the substantial opposition that mobilized against Clay’s scheme and the decades of internal contestation that followed.

The American System provoked James Madison to respond to Clay that “I can not concur in the extent to which the pending Bill carries the tariff, nor in some of the reasoning by which it is advocated.” Jefferson went even further. Writing to Madison, he denounced the tariff internal improvements components alike and suggested that they exceeded the enumerated powers of the Constitution. In one of his last political acts before his death in 1826, Jefferson drafted a proposed resolution for the Virginia General Assembly, condemning Clay’s measures as unconstitutional. These statements marked a sharp turn from each figure’s equivocal acceptance of the Tariff of 1816. The American System, in their minds, pushed protective doctrine far beyond its reasonable constitutional limits, which bound any assessment to the purpose of raising revenue.

Clay’s proposal became a major dividing line in American politics for the next four decades. Tariffs offer lucrative benefits to recipient industries, allowing them to sell their goods at higher prices than under foreign competition. In a typical legislative setting, this means resources are happily diverted into rent-seeking, the process whereby private actors lobby government for favorable laws and regulations that rewards them with private benefits. With protective rates on the table, the tariff issue gave rise to the original lobbying establishment in Washington, DC. The pattern repeated itself every time Congress revised the tariff schedule. Industry representatives flooded the body with requests for preferential rates. Backroom deals were cut to support parallel rates for industries in other districts and states, and bribes changed hands on committee floors. Although Clay packaged his scheme as a strategic and finely tuned economic program, its practical reality turned into a free-for-all of public graft.

Early 19th-century tariffs also depended on the nation’s unpredictable sectional rifts. Southern agricultural exporters who faced price-taker status on a global market generally opposed high tariffs. Industrial mid-Atlantic states became the locus of protectionist doctrine, led by the electoral powerhouse of Pennsylvania. New England sundered into protection-seeking textile mills, a merchant sector that was at times more disposed toward trade, and producers of raw materials such as wool that faced import competition. The western states often functioned as a swing block on tariff issues, making them ripe for legislative logrolling to secure their votes.

For Clay, a slaveowner with reservations about the institution, this caused a conundrum. The underlying economics of the American System involved a strategy of import-substitution wherein southern cash crops would be redirected from Europe to the textile mills of the northeast in exchange for domestically made manufactured goods. By “harmonizing” these chains of production and ensuring a domestic buyer with subsidized transport improvements, Clay aimed to placate the South into the tariff coalition. In doing so, he risked further entrenching slavery. As a solution, Clay appended the American System with a proposed program of compensated emancipation and colonization of freed slaves abroad in locations such as Liberia—an impractical and racially paternalistic scheme that nonetheless continued to influence national policy until the Civil War.

The period between 1824 and 1846 saw a succession of competing tariff policy regimes, vacillating between protection and free trade as legislative coalitions shifted. In 1828, protectionists gained the advantage after a legislative ploy backfired on the free traders. The latter group attempted to load the revised schedule with so many amendments and carve-outs for industry that it would alienate New England’s mercantile businesses and kill the bill. Instead, the “Tariff of Abominations” narrowly passed, raising the average rate on dutiable imports to over 60 percent.

The protectionists’ victory in 1828 and a slightly moderated replacement schedule in 1832 precipitated a political crisis that played out in stages over the next five years. Enraged by the new tariff schedule and looking to deflect national attention away from slavery, South Carolina passed a nullification ordinance against the measure in 1832. The fallout from this measure pitted President Andrew Jackson against his own vice president, John C. Calhoun, prompting the latter to resign his position to take a seat in the Senate. With threats of disunion and a counteracting Force Bill authorizing the president to compel tariff collection with military action if necessary, Calhoun and Clay negotiated a detente. The Compromise Tariff of 1833 gradually reduced rates to their 1816 level over the next decade.

Clay’s Whig Party resumed the upper hand and briefly imposed higher protectionist rates under the Tariff of 1842, only to see their fortunes reversed by the comprehensive overhauls of the Walker Tariff of 1846. This final iteration of the antebellum tariff system established a standardized schedule of ad valorem rates, intended to streamline the complex and cluttered schedules that proceeded it. The Walker act also drastically reduced rates in a free trade direction, although it preserved some “incidental protection” by classifying certain industries on the highest rate schedule. Offered as a reform measure, the tariff reduction intentionally coincided with Britain’s near-simultaneous repeal of the protectionist Corn Laws, leading to another decade and a half of relatively free trade on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Civil War upended trade liberalization under the Walker rates. Tariffs did not cause the war, as some Confederates later alleged in attempts to downplay the central role of slavery. Economic recession in 1857 breathed life into protectionism, making tariffs a regional campaign issue in 1860. The withdrawal of southern states from Congress in the 1860–61 “secession winter” session unexpectedly enabled protectionists to remove a procedural block on the Morrill Tariff bill and secure its passage on the eve of Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration.

National conservatives often celebrate this law because it ushered in a period of high tariff protectionism that lasted until 1913. Their enthusiasm fundamentally misunderstands the measure, which economist William Stanley Jevons denounced in The Coal Question: An Enquiry concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal-Mines (p. 326) as “the most retrograde piece of legislation” to ever emerge from the United States. Like its predecessors, the Morrill Tariff emerged from corrupt bargaining of beneficiary interest groups. Its shortsighted favors to recipient industries infuriated Great Britain, one of the country’s largest trading partners. All else equal, British anti-slavery sentiments should have made them a natural sympathizer with the Union cause during the Civil War. Instead, tariff irritation became a diplomatic blunder that helped push Britain into an uneasy neutrality.

Enjoying the upper hand provided by the Morrill schedule, protectionist interests entrenched themselves in the postbellum period, particularly after fending off a challenge from the free trade wing of the Liberal Republican movement in 1872. National conservatives often point to the high economic growth of the late 19th-century tariff era as “proof” of the American System’s success; however, this position relies on a misreading of evidence.

As economist Douglas Irwin notes, “tariffs coincid[ing] with rapid growth in the late nineteenth century does not imply a causal relationship.” American System proponents failed to articulate the mechanism whereby tariffs contributed to this pattern, amid other complications. For example, many “infant” U.S. manufacturing industries they credit to tariffs began in the comparatively low tariff late antebellum era. Nontraded economic sectors such as utilities also saw faster growth rates and capital accumulation than import-competing manufactured goods in the late 19th century, defying the pattern that the protectionists would predict. Irwin summarily notes that hypothesized “links between tariffs and productivity are elusive.” The claimed correlation with growth is both exaggerated and likely spurious. There’s also evidence that the harms of late 19th-century protectionism outweighed the isolated benefits to selected industries on net. Economist Bradford DeLong identifies two such harms: (1) the loss of agricultural exports to Europe through symmetry effects, effectively harming farmers in order to prop up northeastern industries and (2) higher prices on imported machinery and other capital goods, which likely impaired the pace at which America industrialized.

At the same time, high tariff protectionism continued to attract rent-seeking interest groups. The sheer extravagance of the public corruption around tariff schedule revisions came to a head in the late 19th century, eventually leading reformers to call for the abandonment of a tariff-based revenue system. Since tariffs were ostensibly a revenue device under the Constitution, swapping a different federal tax system would obviate the need for their continuation and thereby break the protectionist interest group coalition. This was the primary argument behind the federal income tax movement that eventually carried the day in 1913.

Tariff reformers had a plan to effect a swap, but they also faced a constitutional obstacle. In the 1895 decision of Pollock v. Farmers Loan and Trust, the Supreme Court struck down a federal income tax provision. It violated the Constitution’s population apportionment requirement for direct taxation, meaning that the case would either have to be reversed or that the Constitution would have to be amended. The latter outcome emerged from a legislative standoff during the Payne–Aldrich tariff schedule revisions of 1909. When Republican Senator Nelson Aldrich opened the revision process to tariff-seeking interest groups, a segment of his party threatened to revolt against the overreach. The combination of these Republican “insurgents” and free trade–aligned Democratic minority cast the chamber into chaos. As a negotiated solution that kept his tariff in place, Aldrich agreed to permit a constitutional amendment authorizing a future income tax. The plan backfired in 1913 after voters swept the Republicans out of office and the newly ratified 16th Amendment authorized the long-sought tax swap.

Protectionism in the Income Tax Era

For a fleeting moment, the tax swap strategy worked. The average tariff rate on dutiable goods had hovered between 40 percent and 50 percent since the Civil War. The Underwood Tariff of 1913 reduced it to less than 20 percent by the end of the decade and compensated for lost revenue by imposing a modest income tax with a top marginal rate of 7 percent on earnings over $500,000 (about $13 million in 2020). The revenue yield from the income tax far exceeded the expectations of its original backers in 1909. Revenue measures prompted by the U.S. entry into World War I hiked the top marginal rate to an astounding 77 percent in 1918, and peacetime measures held it above 50 percent until 1924.

The 16th Amendment completely decoupled tariffs from their function as a revenue source and fundamentally altered the political economy of trade policy. As Frank Chodorov astutely observed on The Income Tax: The Root of All Evil (p. 40), the new “income tax so enriched the Treasury that the revenue from tariffs became unimportant, and the government could afford to give more and more protection to the manufacturers.” Before 1913, the government revenue needs imposed an informal upper boundary on tariff rates, lest Congress “protect” itself into autarky and out of a revenue stream. As the tax swappers discovered to their chagrin in 1922, an alternative revenue source meant all bets were off. That year, the new Republican Congress restored rates to their pre-Underwood levels through the Fordney–McCumber Tariff, framing its provisions as economic stimulus to manufacturing as the economy transitioned away from wartime production.

A relatively strong domestic economy absorbed the resulting price increases, but policymakers took the wrong lessons from Fordney–McCumber. When the stock market crashed in 1929, congressional Republicans already had a second tariff schedule hike on the legislative agenda under the Smoot–Hawley Act. At the introduction of the bill in early 1929, Representative Hamilton Fish of New York appealed to the principles “laid down by Henry Clay—the principle of protecting the home market.” “The question,” Fish continued, “is simply whether you prefer to conserve the home market and protect American wage earners or let the products of low-paid foreign labor destroy the home market for the American producer.”

The emerging recession accelerated the adoption of Smoot–Hawley. Its supporters framed the measure as a stimulus package to insulate American industry from the downturn. In practice, it became a legislative free-for-all of corruption. Almost overnight, the measure raised average tariff rates to nearly 60 percent, a level unseen since the “Tariff of Abominations” a century prior. Special interests flooded committee rooms, exchanging cash under the table for favorable rates to insulate themselves from foreign competitors amid the unfolding downturn. Smoot–Hawley backfired catastrophically. Instead of boosting American industry, it precipitated a trade war of retaliatory measures worldwide. American agriculture bore the brunt of it, as crop exports declined, accelerating the insolvency crisis on farm mortgages. The total volume of world trade (measured in 1934 dollars) declined from almost $3 billion in January 1929 to just $992 million in January 1933.

Despite growing recognition of its error, Congress soon found that it had little recourse to repeal Smoot–Hawley, which remains the official U.S. tariff schedule to this day. Game theory explains the conundrum. Universally high rates had killed off international trade, yet if any individual industry succeeded in retaining beneficial rates for itself while all other rates were lowered, it might find itself reaping high concentrated rewards under isolated protection vis-à-vis the rest of the economy. Although most observers agreed that Smoot–Hawley needed to go, no individual industry would voluntarily relinquish its rates. “The very tendencies that have made the legislation bad,” wrote political scientist E. E. Schattschneider in Politics, Pressures and the Tariff: A Study of Free Private Enterprise in Pressure Politics, as Shown in the 1929–1930 Revision of the Tariff (p. 238), “have … made it politically invincible.”

The solution to the Smoot–Hawley stalemate came through an innovative flanking move. Designed by Secretary of State Cordell Hull, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 (RTAA) shifted the locus of trade policy to the executive branch. While Congress still retained the constitutional power to set the tariff schedule by law, the RTAA codified presidential power to negotiate bilateral trade agreements with other countries. It also established a congressional ratification procedure requiring only a simple majority, as opposed to the supermajority required for a treaty. Since the presidency draws upon a larger national constituency for electoral support, it enjoys comparatively greater insulation from local interest groups that dominate congressional tariff schedule adjustments. The State Department could consequently negotiate more favorable rates than those specified by Smoot–Hawley, effectively bypassing the congressional impasse one nation at a time.

The RTAA’s approach ushered in an unprecedented period of near-continuous trade liberalization. By the end of World War II, the average U.S. tariff rate on dutiable goods dropped from almost 60 percent under Smooth–Hawley to less than 30 percent, without formally changing the tariff schedule. In 1947, its underlying structure provided a model for multilateral trade liberalization under the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), the precursor to today’s World Trade Organization. The RTAA/GATT model is far from free of interest group manipulation—indeed the GATT created numerous antidumping and emergency “escape clause” exceptions taken directly from Smoot–Hawley and Fordney–McCumber. At the same time, its effects are plainly visible in Figure 1. It is noteworthy that over the same period, gross domestic product per capita dramatically rose in the United States (Figure 2). While this growth cannot be exclusively attributed to trade liberalization, it belies the claims of protectionists who erroneously associate the post-war period with American economic decline.

Conclusion

At its heart, the national conservative charge to revive tariffs is an attempt to reverse this pattern and return the United States to the Smoot–Hawley model of congressional primacy in trade policy. They present this objective as part of a historical narrative that appeals to Hamilton and especially Clay and assert an unsubstantiated link between 19th-century economic growth and tariffs. Concurrently, they conspicuously omit any hint of the rampant corruption of tariff schedules in the congressional era, of the many times that tariff hikes backfired from Civil War diplomacy to the economic ruination of the Great Depression, and of the substantial opposition that protectionism faced from other leading figures of the American Founding. As James Madison discovered in 1789, not even the careful checks and balances of the new constitutional system could keep the problem of the faction at bay. Nowhere was this more pronounced than in the new government’s tariff power. Some 230 years later, we are still grappling with Madison’s lessons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.