A recent headline exclaimed: “Central Banks Should Raise Rates Sharply or Risk High-Inflation Era, BIS Warns.” The Bank for International Settlements is owned by 61 central banks, so they should know better than to equate higher interest rates with lower inflation.

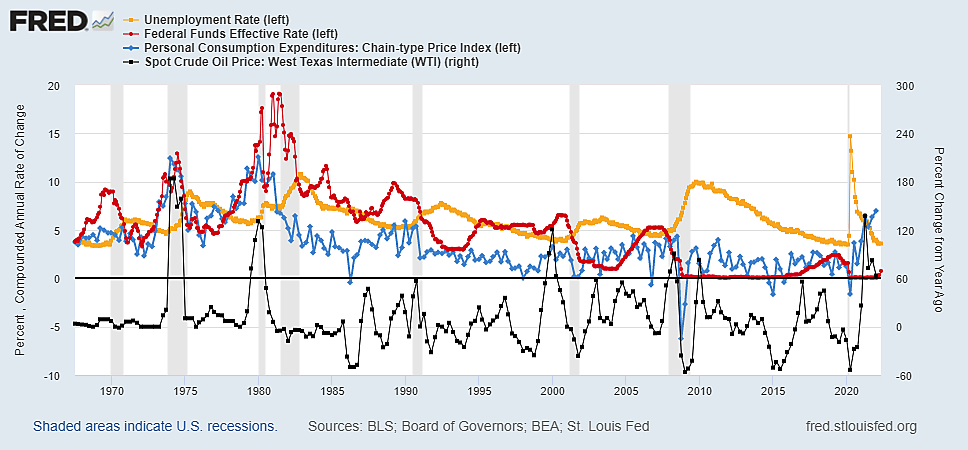

Countries with the lowest central bank interest rates (below zero) include Switzerland and Japan, according to the BIS.

Those with the highest policy rates include Argentina and Turkey, with rates of 49% and 14% respectively.

Should we conclude that Argentina and Turkey are valiantly fighting inflation with high interest rates while Switzerland and Japan are pursuing wildly inflationary easy money policies? That would be preposterous. The latest year-to-year CPI inflation was 2.9% in Switzerland and 2.4% in Japan, but 60.7% in Argentina and 73.5% in Turkey.

Even within the Euro bloc, countries which share the ECB below-zero policy rate face higher 10-year bond yields if their inflation is higher: France his 5.2% inflation and 2.3% bonds; Greece has 11.3% inflation and 3.9% bonds.

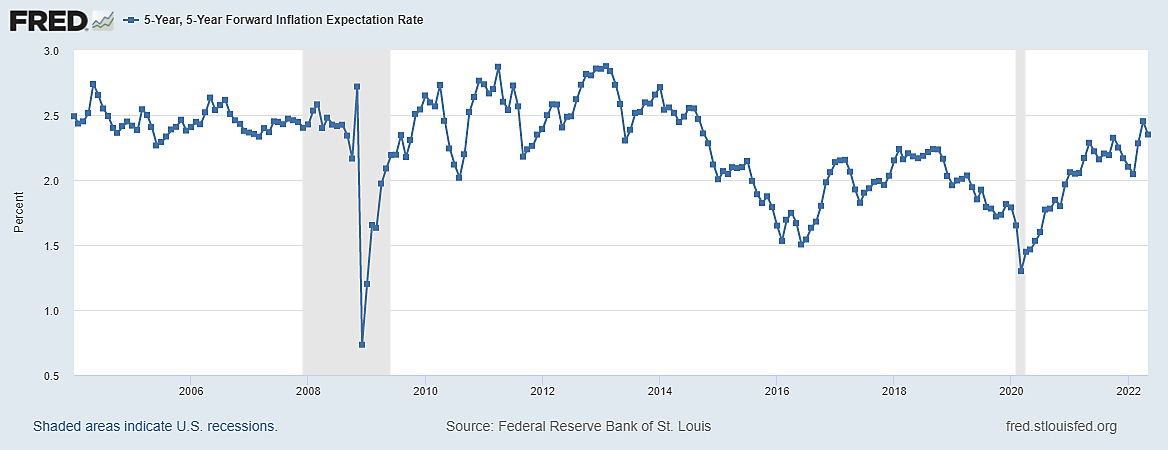

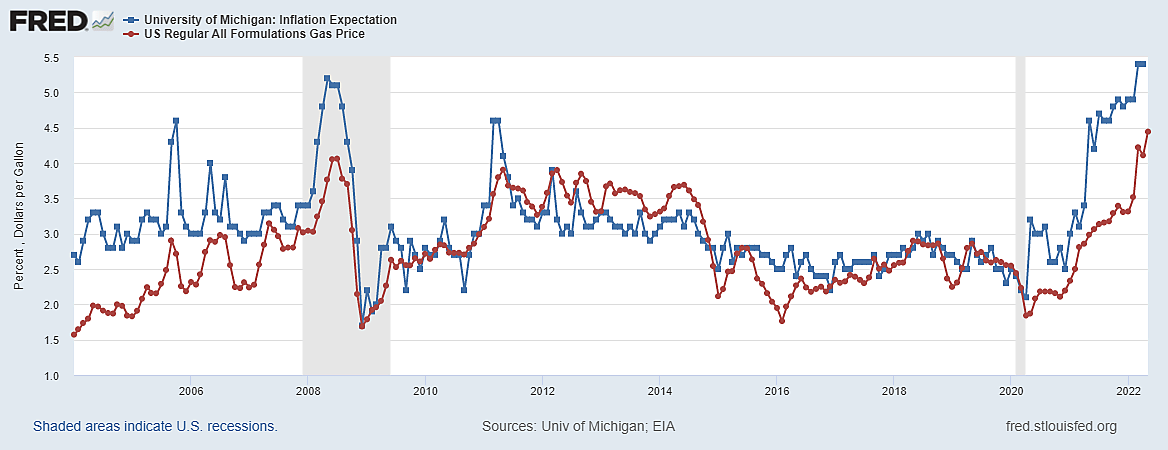

Irving Fisher of Yale (1867–1947) taught that nominal interest rates consist of a relatively small real rate (linked to the real return on capital) plus an inflation premium. That is why countries with high inflation have high interest rates, and why periods of low inflation in the U.S. also had a low federal funds rate. It would be paradoxical to expect high nominal interest rates to result in sustained low inflation.