The Producer Price Index (PPI) is not a measure of inflation in the cost of living. It estimates prices businesses receive, not prices consumers pay. Importantly, it includes soaring export prices for U.S. on food and energy, which had already risen 4.5% in the month of March, 3% in February, and 2.8% in January due to sudden global scarcity in the wake of the Russian war and sanctions.

The PPI “increased 0.5 percent in April…[partly because] construction increased 4.0 percent, while prices for final demand services were unchanged.” “The indexes for final demand trade services and for final demand services less trade, transportation and warehousing declined 0.5 percent and 0.1% respectively. (Trade measures changes in [profit] margins received by wholesalers and retailers.”

To repeat, the PPI is not a measure of inflation. It includes profit margins in retailing and wholesaling, prices foreigners paid for U.S. grain and LNG, plus other irrelevant miscellany. It does try to estimate some service prices, from the firm’s perspective, but excludes housing and other key services which are properly included in the CPI.

Put the PPI aside and take a closer look at commodities and services in the April CPI. Commenting on recent differences between inflation in goods and services, Jason Furman (former chairman of President Obama’s CEA) recently offered some unique insights:

“This is the inflation story to worry about: core services inflation has increased for four straight months. We’re getting the much predicted/hoped for reprieve on goods price increases but services matter 5X in the computation of the CPI.”

He offers a graph showing low inflation in prices of durable commodities over the past three months (falling used car prices in April largely offset rising new car prices), but he worries about higher inflation in prices of what he calls “core services.”

Mr. Furman’s distinction between prices of commodities and services is instructive and useful. Higher interest rates might further weaken the already slowing prices of durable goods, for example, but higher interest rates cannot have much impact on sticky prices negotiated for yearly apartment leases (which are counted as housing services).

Unfortunately, his definition of “core” service inflation is not comparable to core commodity inflation. It has nothing to do with food prices and excludes only those energy costs that households pay directly for electric and gas utilities. Prices of “services less energy services” in the CPI are exaggerated by the war-related surge in oil prices because such services include transportation services. And “public transportation” includes airline fares – which rose 21.9% in the month of April, or 18.6% on a seasonally-adjusted basis. That was not driven by runaway consumer demand (airline bookings fell 17%), but by the exploding price of jet fuel.

Note that the “all items” headline CPI also includes airline fares, which is just one reason that even the “core” CPI does not actually exclude energy prices despite professing to do so. If airline fares had been prudently excluded from the “all items” CPI, that would have lowered both headline and core inflation.

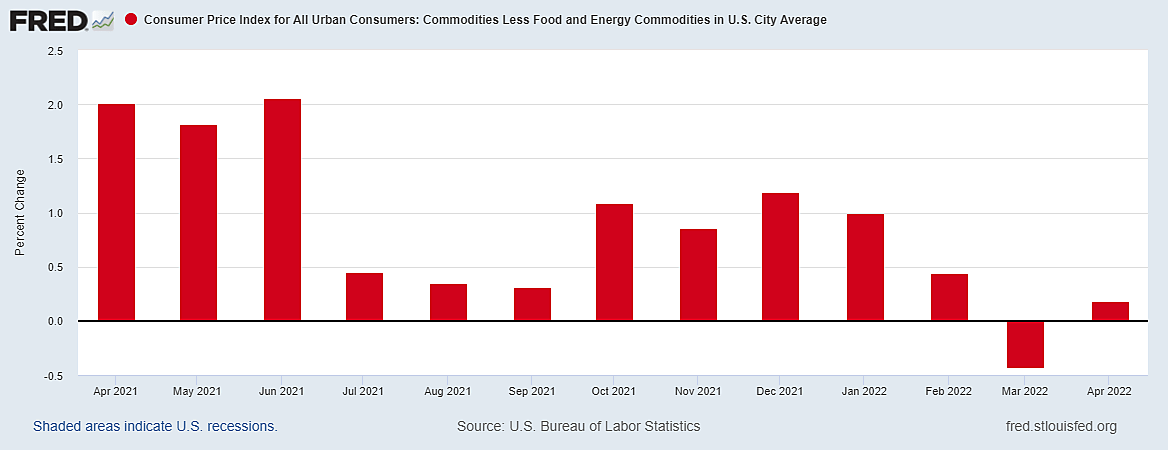

Turning now from services to goods, it is not just durable commodity prices that have slowed since January, as Furman emphasizes, but all core commodity prices. Prices of commodities less food and energy did not rise at all last month, according to the Consumer Price Index. They were unchanged. That zero increase was seasonally adjusted into a modest 0.2% rise in April, and it followed a 0.4% decline in core commodity price in March.

Despite the zero increase in unadjusted core commodity prices for two months, they were nonetheless 9.7% higher than in April 2021 which tells us something about past inflation but nothing about recent months. Core commodity inflation was remarkably high in April, May, and June of 2021 in the wake of the large March 2021 fiscal stimulus checks. By contrast, core commodity inflation was remarkably low this March and April – zero, in fact.