-

The idea that free trade would set off a race to the bottom is a myth. In the era of globalization, wages have increased, jobs have become safer, and child labor has declined.

-

Companies and investors are not searching for the poorest places to do business but are investing mostly in relatively wealthy countries. When they do invest in poor countries, their main effect is to raise productivity and labor standards.

-

There also is no environmental race to the bottom. The richer countries are, the more they protect their environment, and trade speeds up the transition to new and greener technologies around the world.

In 2002, Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz claimed that “globalization has become a race to the bottom, where corporations are the only winners and the rest of society, in both the developed and developing worlds, is the loser.”

Around the turn of the millennium, the fear of such a race to the bottom started haunting the debate about economic globalization. As capital and corporations became freer to move across borders, many worried that they would move to places with the lowest wages, worst working conditions, and least environmental protection. People believed that governments would be tempted to loosen standards to attract more investments and increase its participation in global supply chains.

But since then, the opposite has happened. The overall direction is one toward better jobs, higher wages, safer workplaces, and less child labor, and it has happened the fastest in the countries that have opened the most and are most integrated in global supply chains.

Astonishingly, these data are ignored by officials in the United States and elsewhere who—parroting Stiglitz two decades ago—still cling to the race-to-the-bottom narrative and decry a “colonial” and extractive economic model supposedly fueled by “traditional free trade agreements,” as U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai put it in a recent speech on supply chain resilience. It’s long past time for them and other globalization skeptics to update their script.

What Has Happened to Work?

One typical op-ed in the New York Times asserted in 2015 that the race to the bottom encourages corporations to “relocate production to the lowest-cost country,” employ children because they are paid less, and neglect safety measures, resulting in the deaths of more workers. This has always been a theoretical possibility, but empirical data have stubbornly refused to cooperate with it.

The International Labour Organization considers the share of the labor force in elementary and lesser-skilled jobs as a proxy for low incomes and bad working conditions. This share has declined by more than 10 percentage points globally from 1994 to 2019. The decline was 6 percentage points in low-income countries and as much as 20 percentage points in upper-middle-income countries, the group of countries that have taken the greatest leaps to integrate with the global economy.

The number of working poor has declined very fast. Between 1994 and 2022, the share of employed persons worldwide who live in extreme poverty (receiving an income below $1.90 adjusted for inflation and local purchasing power) declined by more than three-quarters, from 31.6 percent to 6.4 percent—a reduction of more than half a billion people despite setbacks during the pandemic (Figure 1). The share of workers in moderate poverty (earning between $1.90–$3.20) also declined, from more than 21 percent to around 12 percent. Poverty is strongly correlated with gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and in upper-middle-income countries, the share of extreme working poor was less than 1 percent in 2022.

In East Asia, the developing region that has globalized the most, the share of workers in extreme poverty was just 0.5 percent in 2022. In contrast, the region with the least foreign investment and participation in supply chains, sub-Saharan Africa, had a rate of 38 percent.

It is more difficult to come up with comparable measures of labor standards, but the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization have created a global set of estimates of work-related injuries and deaths between 2000 and 2016. Their data show a “substantial reduction in the total work-related burden of disease.” The loss of disability-adjusted life years attributable to occupational risk decreased by 12.9 percent between 2000 and 2016. The global rate of deaths related to work declined by 14.2 percent. The death rate from exposure to mechanical forces and fire or heat, two risks often associated with sweatshops in poor countries, declined by 18.3 percent and 26 percent, respectively.

Child labor declined fast over the same period. Between 2000 and 2020, the share of children aged 5 to 17 years who were active in work that they were too young to perform or that was likely to harm their health or safety declined from 16 percent to 9.6 percent. The share of children performing hazardous work was reduced by more than half, from 11.1 percent to 4.7 percent (Figure 2). Children are three times more likely to work in rural areas than in urban areas and seven times more likely to work in agriculture than in industry.

On the whole and on average, jobs have become better paid and safer in the era of globalization, the complete opposite of what the race-to-the-bottom hypothesis predicted. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) concludes its review of the research:

Indeed, the worst of fears about a race to the bottom do not appear to have materialised systematically in the real world, though examples do arise. A large empirical literature seems to point, if anything, to the opposite conclusion.

Are We Racing to the Bottom on Labor Conditions?

This encouraging development did not happen despite globalization but to a large extent because of it. Using data from 114 countries, Andreas Bergh and Therese Nilsson found that increased globalization in a country, as measured by the KOF Globalisation Index, is associated with significantly faster poverty reduction.

In his book Globalization and Labor Conditions, Robert Flanagan summarizes the evidence: “Countries that adopt open trade policies have higher wages, greater workplace safety, more civil liberties (including workplace freedom of association), and less child labor.” Flanagan and Niny Khor also document this relationship in “Trade and the Quality of Employment: Asian and Non-Asian Economies,” in the OECD report Policy Priorities for International Trade and Jobs.

This would be extremely surprising if companies always scoured the globe searching for the lowest-cost country. But they don’t. If they did, 100 percent of foreign direct investment would go to the least developed countries, but in fact, no more than 2 percent of all foreign direct investment is heading in their direction. Most investment goes to relatively developed countries, and GDP per capita is the strongest influence on labor conditions. On average, richer countries have higher wages, safer jobs, shorter working hours, and stronger labor rights, such as freedom of association and less forced labor.

The race-to-the-bottom hypothesis got it wrong because it neglected half the cost-benefit analysis. If labor compensation (in the broad sense, including working conditions) were just a gift generously bestowed on workers, it would make economic sense to reduce it as much as possible, but in a competitive labor market, it is compensation for the job that someone is doing, and therefore there is a tight link between pay and productivity. Some workers might be twice as well paid as others, but that does not make them uncompetitive if they are also twice as productive.

This is not the only flaw in the race-to-the-bottom hypothesis. Foreign trade and investment do indeed find their way to the poorest countries sometimes, especially in sectors where low capital investment means that labor costs are an important factor, such as the production of garments and footwear. But in those instances, their main effect is to raise the level of productivity and to improve wages and working conditions.

These jobs might look bad to journalists and activists in rich countries, who are used to much higher standards, but they usually offer something much better for people in poorer countries. Compared with the alternatives in agriculture, services and domestic manufacturing, these factories offer better pay and working conditions. In fact, when the World Bank writes about how the Cambodian economy could improve the quality of jobs, it offers a recommendation that seems completely counterintuitive to the critics in rich countries: “Use the same labor standards applied in the garment factories to other industries and sectors.”

The emergence of international supply chains has meant that multinational companies now consider suppliers in a poor country an integral part of their own business. Therefore, it is in their own commercial interest to spread the latest technology and business processes that they need to produce better and cheaper. In this way, many poor countries, such as China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam, as well as more developed ones, such as Poland and Romania, have been able to skip several stages of development and have managed to grow at a fast pace. And once you have built factories, roads, and ports to manufacture and transport clothes and shoes, you can also use them to produce and export high-tech components.

This enables workers to produce more value, and therefore they receive better compensation. Research consistently shows that manufacturing firms pay better than other firms, export firms pay higher wages than producers for the domestic market, and foreign-owned companies pay higher wages than comparable local companies—between 16 and 40 percent more in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. There is also a positive effect on wages in local businesses that participate in international supply chains.

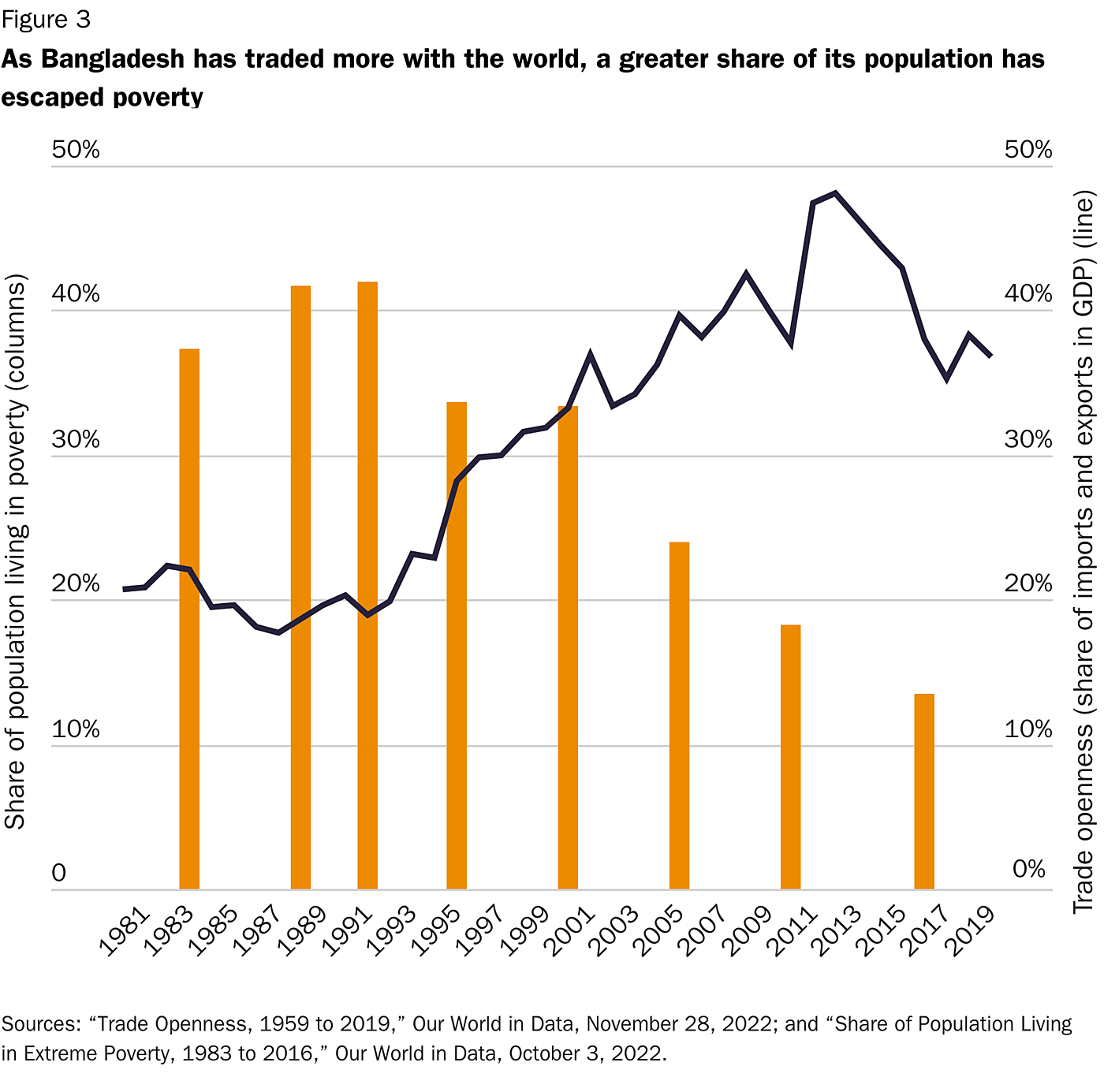

Bangladesh is an illustration of this globalization success story. After having acquired outside know-how and machinery in the 1980s, local entrepreneurs quickly turned the country into a global powerhouse for textile manufacturing. Before 1980, the desperately poor country did not have any factories that produced textiles and garments for exports; today, the sector contributes more than 13 percent of GDP and 80 percent of exports. This has created millions of jobs, especially for women. The economy has grown rapidly, and according to the World Bank, extreme poverty has been reduced from over 40 percent in 1991 to less than 14 percent in 2016 (Figure 3).

As new businesses attract workers, old ones have to improve their offers to workers. In 2003, a Vietnamese factory owner outside Ho Chi Minh City told me that competition from factories producing for Nike has changed his perspective on the importance of labor standards:

The management of the Nike factory has understood how to make the employees satisfied. And I have seen that productivity comes not only from the machines, but also from the satisfaction of the workers. So when we now build a new factory, working conditions are one of the things we will concentrate on.

There are certainly instances of bad working standards even in companies producing for global markets, but there is “virtually no careful and systematic evidence demonstrating that, as a generality, multinational firms adversely affect their workers, provide incentives to worsen working conditions, pay lower wages than in alternative employment, or repress worker rights,” according to Robert E. Baldwin and L. Alan Winters in the 2004 report Challenges to Globalization: Analyzing the Economics, who go on to say, “In fact, there is a very large body of empirical evidence indicating that the opposite is the case.”

As poor countries are integrated in international supply chains, there is also more pressure from Western consumers and watchdogs to root out abuse and bad working conditions. One example is the reaction after the deadly collapse in 2013 of Rana Plaza, an eight-story commercial building in Bangladesh that housed many garment factories producing for Western brands. After the disaster, hundreds of American and European businesses signed two different initiatives that committed their local suppliers to safety inspections and improvements and provided funding for it. Safety committees were introduced as well as a mechanism whereby workers could raise concerns anonymously.

Since then, tens of thousands of factory inspections have taken place; electrical upgrades, fire alarm systems, fire doors, and sprinkler systems have been installed; and building foundations have been improved. Almost 200 factories that did not fulfill their commitments had lost their contracts by 2021.

In fact, even critics tend to agree that multinational companies have this effect. For example, in a book attacking global capitalism, Noreena Hertz admits that foreign corporations “usually pay higher wages and offer better working conditions than local corporations” and that they “often improve local conditions by exporting their own standards instead of adapting to local ones.”

Trade is also a remedy for child labor and helps to explain the declines shown in Figure 2. As parents get better jobs, they can afford to forgo their children’s wages and instead invest in their education. One study found that a 10 percent increase in a country’s economic openness is associated with a 7 percent decrease in child labor. However, there is a surprising and important variation difference in effects depending on how regional trade agreements are designed. Agreements without social clauses that ban child labor increase school enrollment and reduce child labor, but perversely, trade agreements that ban child labor reduce school enrollment rates and increase child labor. The explanation seems to be that a ban on child labor depresses child wages, so poor households who rely on their wages have to make up for it by putting more children to work more hours in the domestic and often informal economy. In other words, opening opportunities for lesser-skilled exports is a better way to combat child labor than bans.

Do We Trade Away the Planet?

At first look, the case for a possible race to the bottom when it comes to the environment is stronger. Competition forces businesses to compensate workers better when they get more productive opportunities, but there is no similar mechanism to increase the protection of a public good such as the environment, and if it entails costs for businesses, they might move elsewhere. Whether this is the case is an empirical question.

In an influential 2005 study, economists Jeffrey Frankel and Andrew Rose presented two important findings about trade and the environment. One was the so-called Kuznets curve, which posits that many forms of environmental degradation look like an upside-down U. As countries urbanize and industrialize, the damage to nature and health increases rapidly, but at a certain point the curve reverses and increased incomes lead to environmental improvements. Therefore, because trade contributes to growth, it may initially harm the environment in low-income countries while improving it in middle- and high-income countries.

The idea of an environmental Kuznets curve is often dismissed in the debate because there is no automatic relationship between growth and the environment, and the relationship between economic growth and the environment differs depending on which environmental factor is considered, but the empirical relationship is now well established by researchers. After a certain point, richer populations start seeing the environment as more of a concern. They elect politicians who take the issue more seriously, and they acquire the economic resources and technological capabilities to develop and adopt greener technologies.

The Environmental Performance Index (EPI), by Yale University and partners, regularly ranks the ecological sustainability of 180 countries. It looks at 40 different performance indicators, including biological diversity and air pollution. The world’s countries are very clearly grouped according to level of prosperity and region. High-income market-based democracies take all the top 30 places in the index, while the bottom is mainly made up of African countries and the poorest Asian countries.

The EPI’s own conclusion is that “scores show a strong correlation with country wealth,” although of course there are countries at every level of prosperity that perform better or worse (Figure 4). The correlation is not automatic but has strong empirical support. Likewise, the OECD describes how its own measures of national environmental policy show “a significant positive correlation with GDP per capita, confirming that richer countries tend to have more stringent policies.”

The second part of Frankel and Rose’s study looked at the amount of trade at different countries’ income levels and its relationship with air pollution. It turned out that increased trade as a share of GDP correlates with reduced air pollution, independent of the effect wealth had on environmental progress. Rather than leading to a race to the bottom, globalization appears to be creating a race toward greener pastures and cleaner air.

This is primarily because trade encourages the transmission of know-how and technology. This lowers the price of greener methods and products, making them more attractive to local companies and consumers. Poor countries with greater environmental challenges can learn directly from what richer countries have done and avoid repeating their mistakes. Developing lead-free gasoline and catalytic converters is difficult and costly, but once they have been developed, poor countries can adapt to them faster and cheaper.

Multinational companies bring the latest methods to the countries they invest in, and these usually use less energy and raw materials than older ones. More trade can also create pressure to improve local environmental regulations, as consumers and organizations in rich countries demand responsibility throughout the supply chain.

The picture has been somewhat complicated by later studies of particular regulations. There are plenty of examples of rapidly increasing restrictions on emissions harming industries and benefiting competitors in poorer countries with less protection. The consequence is that wealthy countries import back some of that pollution from other countries. This means there is a certain leakage when we impose higher costs.

However, the notion that countries would dismantle their environmental protection to attract investors is not correct. On the contrary, national environmental measures are tightened globally as countries get richer, albeit at different rates. Remarkably, according to the OECD’s measures, average environmental protection is now stronger in the BRIICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa) than it was in Sweden, the UK, the United States, and almost all other rich countries in 1995.

Is CO2 an Exception?

Frankel and Rose’s study did, however, show that one form of emissions had not decreased with increased prosperity; on the contrary, it continued to increase: carbon dioxide. Nor were the authors hopeful that it would decline, since these emissions mostly affected people in other places, giving less incentives to limit them. The major change since their results were published is that something is happening even in this case.

Since 2010, more than 40 countries have reduced their carbon dioxide emissions in absolute terms while also growing their economies (Figure 5). These are mostly the very richest countries, which indicates that there is a Kuznets curve even for CO2 emissions, although with the characteristic that it turns downward at a significantly higher level than for other emissions. This curve begins to slope downward earlier in more economically free countries.

As we get richer, we develop more energy-efficient products and processes and turn more goods into ones and zeros in digital systems. In the world as a whole, the energy required to produce one unit of GDP fell by 36 percent between 1990 and 2020. Low- and middle-income countries have made an even faster journey because they have been able to move quickly from old, dirty technology to the very latest, which they imported. China’s energy intensity fell by a whopping 72 percent during this period.

Furthermore, an ever-smaller part of this energy production requires fossil fuels when, for example, the price of solar power plummets. From 2009 to 2019, the price of electricity from onshore wind fell by 70 percent and unsubsidized solar by an incredible 89 percent. This was made possible thanks to economies of scale. Innovation makes panels more efficient, large factories turn complicated processes into routine manufacturing, and more-efficient mining operations and processing of raw materials make inputs cheaper.

Such huge investments can only be profitable if the producers have access to the combined purchasing power of many foreign markets. It would, for example, be completely pointless to develop technologies for fossil-free steel in a country as small as Sweden, for 10 million consumers, if the end result could not be exported to the rest of the world.

The combination of increasing wealth, the spread of technology, and economies of scale clearly make open economies a force for higher environmental standards. In fact, the team behind the EPI explored how its results compared with broad measures of economic liberalism (including property rights, free enterprise, and free trade):

We find that economic liberalism is positively associated with environmental performance. While our results do not give countries carte blanche to pursue laissez-faire economic strategies without regard for the environment, they do cast doubt on the implicit tension between economic development and environmental protection.

Researchers disagree about why this is the case. Some think it can be explained exclusively by the fact that free markets increase GDP per capita, while others find an additional pro-environment effect of free markets independent of wealth. However, the exact channel is not important for our purposes here. Each of these possibilities would be a decisive stroke against the race-to-the-bottom hypothesis, which posits market liberalization as the problem when in fact it is the solution.

Conclusion

The race to the bottom is a myth. Wages and working standards have not deteriorated in the era of globalization but improved, and they have done so the most in countries that have integrated the most into the global economy. Companies and investors are not searching for the poorest places to do business but instead invest mostly in relatively wealthy countries. More importantly, when they do invest in poor countries, their main effect is to raise productivity and compensation. If this is exploitation, the only thing that’s worse than being exploited is not being exploited.

Also, there is no race to the bottom in environmental standards. Rich countries do not imitate the environmental standards of poor ones; instead, poor countries are catching up with rich ones in environmental sustainability. The richer countries are, the more they protect their environment, and free markets also speed up the transition to new and greener technologies around the world. As long as markets are open and trade is free, there is no race to the bottom, but there is one to the top.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.