Last week during one of their debates, all Democratic primary candidates supported government health care for illegal immigrants. This type of position is extremely damaging politically and, if enacted, would unnecessarily burden taxpayers for likely zero improvements in health outcomes. I expect the eventual Democratic candidate for president to not support this type of proposal, but it should be nipped in the bud.

After the debate, Democratic candidate Julian Castro argued that extending government health care to illegal immigrants would not be a big deal. “[W]e already pay for the health care of undocumented immigrants,” Castro said. “It’s called the emergency room. People show up in the emergency room and they get care, as they should.” It is true that some illegal immigrants use emergency room services thanks to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act and to Emergency Medicaid, but Castro leaned heavily into a stereotype often used by nativists. According to a paper published in the journal Health Affairs, illegal immigrants between the ages of 18–64 consumed about $1.1 billion in government healthcare benefits in 2006 – about 0.13 percent of the approximately $867 billion in government healthcare expenditures that year. That’s a fraction of the cost that would be imposed on American taxpayers by extending nationalized health care to all illegal immigrants. So, with all due respect to Mr. Castro, we do not already pay for their health care just because some illegal immigrants visit emergency rooms at government expense.

One of the reasons why immigrants individually consume so much less welfare than native-born Americans is that many of them do not have legal access to these benefits. Cato scholars have proposed making these welfare restrictions even stricter to deny benefits to all non-citizens and to not count work credit toward entitlements until immigrants are naturalized citizens – what the late Bill Niskanen called “build a wall around the welfare state, not around the country.”

Many American voters are concerned about immigrant consumption of welfare benefits. In a 2017 poll, 28 percent of Americans agreed with the statement that “Immigration detracts from our character and weakens the United States because it puts too many burdens on government services, causes language barriers, and creates housing problems [emphasis added].” That level of concern exists under current laws that restrict non-citizen access to benefits and even chill eligible non-citizen participation. I’d expect that poll result to worsen if new immigrants, especially illegal immigrants, were put on government health care program.

Extending government health care to illegal immigrants and other new immigrants would probably not improve healthcare outcomes for immigrants. According to the wonderful The Integration of Immigrants into American Society report published by the National Academies of Sciences, immigrants already have better infant, child, and adult health outcomes than native-born Americans, while also having less access to welfare benefits like Medicaid. Immigrants also live about 3.4 years longer than native-born Americans do. Illegal Mexican immigrants had an average of 1.6 fewer physician visits per year compared to native-born Americans of Mexican descent. Other illegal Hispanic immigrants made an average of 2.1 fewer visits to doctors per year than their native-born counterparts. Illegal immigrants are about half as likely to have chronic healthcare problems than native-born Americans. Overall per capita health care spending was 55 percent lower for immigrants than for native-born Americans.

Immigrants also lower the cost of other portions of the health care system. In 2014, immigrants paid 12.6 percent of all premiums to private health insurers but accounted for only 9.1 percent of all insurer expenditures. Immigrants’ annual premiums exceeded their health care expenditures by $1,123 per enrollee, for a total of $24.7 billion. That offset the deficit of $163 per native-born enrollee. The immigrant net-subsidy persisted even after ten years of residence in the United States.

From 2002–2009, immigrants subsidized Medicare as they made 14.7 percent of contributions but only consumed 7.9 percent of expenditures, for a $13.8 billion annual surplus. By comparison, native-born Americans consumed $30.9 billion more in Medicare than they contributed annually. Among Medicare enrollees, average expenditures were $1,465 lower for immigrants than for native-born Americans, for a difference of $3,923 to $5,388. From 2000 to 2011, illegal immigrants contributed $2.2 to $3.8 billion more than they withdrew annually in Medicare benefits (a total surplus of $35.1 billion). If illegal immigrants had neither contributed to nor withdrawn from the Medicare Trust Fund during those 11 years, it would become insolvent 1 year earlier than currently predicted – in 2029 instead of 2030.

American taxpayers should not have to pay for the health care costs of other Americans, let alone for non-citizens. For those reading this post who are very concerned about the well-being of immigrants, think of what would happen to public support for legal immigration if welfare benefits were extended in this way. Immigrants come here primarily for economic opportunity, not for government health insurance. They tend to be healthier than native-born Americans and lower the price of health care for others as a result – but the point would likely change if the laws were different. Let’s not build public support for reducing legal immigration, or increase reluctance to expand it, by extending government health care, at enormous public cost, to people who don’t need it.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Immigration

77% of Drug Traffickers Are U.S. Citizens, Not Illegal Immigrants

When people think of drug smugglers, they often imagine illegal immigrants sneaking into the United States across the southwest border. But the reality is that the vast majority of drug smuggling occurs at ports of entry (including airports), and the vast majority of traffickers are U.S. citizens. According to data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission, U.S. citizens had 77 percent of federal drug trafficking convictions in 2018. This percentage has grown from 69 percent in 2012. As Figure 1 shows, the share of drug traffickers who were illegal immigrants fell from 21 percent in 2012 to 16 percent in 2018.

The reason that drug traffickers are largely U.S. citizens is because most drug trafficking occurs at ports of entry because most drugs—other than marijuana—are easier to conceal in legal luggage than while crossing the Rio Grande or the desserts in Arizona. Figure 2 shows the location where Customs and Border Protection seizes drugs by drug type. Port officers seized between 80 and 90 percent of every major drug type except for marijuana. Even there, officers at ports made nearly half of all the seizures so far in 2019.

Congress should not treat illegal immigrants as if they dominate drug trafficking nor should it focus drug interdiction resources between ports of entry where little drug trafficking takes place. The only thing that has reduced drug trafficking at all has been legalization of marijuana at the state level, which shifted supply away from Mexico and to the United States.

Note on comparisons: While 16 percent of trafficking convictions is about five times illegal noncitizens’ share of the U.S. population, this is not an appropriate comparison because the criminal offense inherently involves movement between two countries, so the relevant population includes people residing on both sides of the border. This means that the potential pool of undocumented noncitizen drug smugglers is vastly greater than the 10.5 million illegal residents already living in the United States.

Any of the 7.5 billion undocumented noncitizens around the world could decide tomorrow to attempt to bring drugs into the United States. Only 2,910 were convicted of doing so. That’s 0.00004 percent of all undocumented noncitizens worldwide. By comparison, 14,146 of the approximately 310 million U.S. citizens did so or 0.005 percent.

Obviously, this exercise doesn’t really tell us much, but the bottom line is that these conviction figures cannot be used to say how likely it is for undocumented noncitizens who are in the United States to be convicted a drug trafficking offense. That is not the point of this post. The point is to dispel the myths that undocumented noncitizens control most drug trafficking to the United States and that traffickers rely primarily on illegal immigration between ports of entry to bring drugs to this country.

-Update added 7/8/2019

Related Tags

Are CBP’s Filthy and Inhumane Immigrant Detention Camps Necessary?

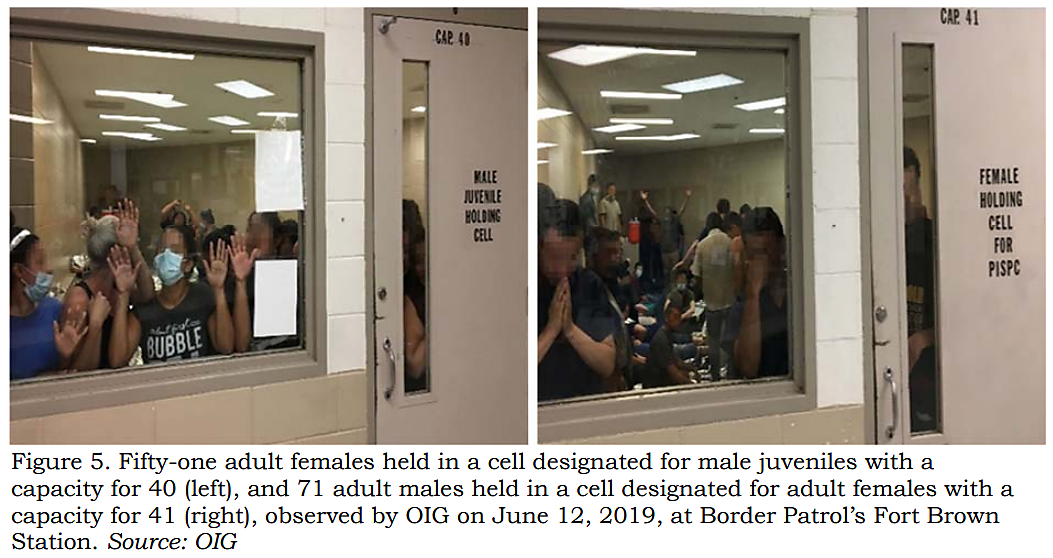

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published a report about detention facilities operated by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) yesterday describing “dangerous overcrowding and prolonged detention of children and adults in the Rio Grande Valley.” This report came just over a month after DHS OIG’s May 30 report on “dangerous overcrowding” in El Paso.

What are the conditions in CBP’s detention camps?

Across the entire border, CBP was detaining from May to June between 4 and 5 times as many people as its facilities were designed to hold. It is impossible to list here everything that the OIG reports exposed, but here are some of what they found:

- A cell with a maximum capacity of 35 held 155 detainees

- A cell with a maximum capacity of 8 held 41 detainees

- Detainees were wearing soiled clothing for days or weeks.

- Children at three of the five Border Patrol facilities visited had no access to showers

- Most single adults had not had a shower in CBP custody despite several being held for as long as a month

- Some single adults were held in standing room only conditions for a week

- Detainees standing on toilets in the cells to make room and gain breathing space, thus limiting access to the toilets

- A diet of only bologna sandwiches. Some detainees on this diet were becoming constipated and required medical attention.

- Standing-room-only conditions for days or weeks.

The OIG found that hundreds of children had been detained in these conditions for more than a week. Dozens of children who were under the age of 7 were held for over 2 weeks. Adults were being caged for a month in unsanitary conditions that were spreading illness. Infamously, the Department of Justice is defending these conditions by arguing that a “safe and sanitary” requirement does not require sleep, toothbrushes, or soap for children. CBP stashed families outside sleeping on the ground under a bridge for days as they were “bombarded with pigeon droppings.” When that was discovered, CBP hid what observers are calling “human dog pounds” elsewhere—again, outside in 100+ degree temperatures.

Other documentation of the depraved treatment elsewhere has come to light. Children told a federal court that infants are being forced to wear “clothing stained with vomit.” Lawyers who inspected the conditions told the New Yorker that during a lice outbreak, Border Patrol had children sharing combs and then when one of these combs was lost, the agents took away their blankets and mats as punishment. A doctor received access to a facility only after a flu outbreak that Border Patrol agents failed to contain had sent five infants to the hospital. Her visit found “extreme cold temperatures, lights on 24 hours a day, no adequate access to medical care, basic sanitation, water, or adequate food.”

Are CBP’s detention conditions a problem?

Yes. CBP has reported the deaths of six children so far this fiscal year after no children had died in the last decade. At least four other adults have also died this fiscal year. Another man committed suicide last year after Border Patrol took away his child and forced him into a detention facility. The conditions are rapidly spreading diseases between detainees, and the OIG found that this was also leading to illnesses among the agents themselves. Border Patrol told the OIG that it believes that holding people in these conditions “could turn violent.” Some agents are even retiring or quitting to avoid the situation. Agents told OIG that the situation is “an immediate risk to the health and safety not just of the detainees, but also DHS agents and officers.”

More fundamentally, the detention conditions are a monstrously unjust way to treat peaceful people. Violent felons and murderers receive better treatment in every state than CBP’s treatment of immigrants and asylum seekers.

Are CBP’s detention conditions violating its own standards?

Yes. CBP’s “Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search” (TEDS) standards provide that showers should normally be provided to children within 48 hours. TEDS standards require children and pregnant women receive at least two hot meals per day and that all detainees not be held in “hold rooms or holding facilities” for more than 72 hours. The OIG found children without any access to a shower at all, even though nearly 30 percent had already passed a 72-hour threshold for release and that they received no hot meals until OIG showed up. It found that the agency also violated a requirement that the fire marshal limit on cell occupancy not be exceeded.

Are CBP’s detention conditions violating the law or the Constitution?

Probably. The William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2008 requires that CBP transfer unaccompanied children (i.e. children without a legal guardian) to shelters run by Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within 72 hours except in “exceptional circumstances.” Moreover, the Flores agreement—which is a court settlement agreement enforced by the District Court for Central California—also requires that all children not be detained for more than 3 days except in the case of an “influx” in which case the standard is “as expeditiously as possible.”

Because immigrants are civil detainees, the 5th amendment of Constitution’s guarantee of protection against punishment without due process of law applies. In this case, given that these conditions are worse than those for convicted criminals or pre-trial detainees, they are definitionally punitive. The American Immigration Council has a lawsuit that may go to trial this Fall to stop these unconstitutional practices.

Is CBP detention legally required?

No. No one appears to disagree with the conclusion that detention is discretionary. Section 212(d)(5)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act grants DHS the authority to “parole”—that is, waive entry restrictions—and allow an immigrant entry to the United States in cases of “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” The dangerous conditions at these Border Patrol stations would easily meet either criteria. The leadership of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—the interior enforcement agency—told the OIG that “if [Border Patrol] feels that they are at a breaking point with managing the masses, [it] has the authority to release” (p. 112). Moreover, CBP itself told the OIG in May that it could process “for immediate release under an order of recognizance.”

Are there security concerns associated with release?

No. The share of criminal aliens apprehended at the border is at an unprecedented low. Despite twice as many apprehensions in 2019, there were half as many criminal aliens. Just 1,214 immigrants apprehended at the border had a criminal conviction for something other than crossing illegally. That is 0.15 percent of all apprehensions this year. These aliens are expeditiously removed from the United States and are not the cause of the overcrowding.

Is the number of immigrants arriving the reason for lengthy CBP detention?

No. The reason that immigrants are languishing for weeks in detention is not a consequence of the daily intake, but the daily output. The OIG found that Border Patrol is “able to complete immigration processing for most detainees within a few days.” At any given time, more than half of all CBP detainees have already completed the CBP intake process (medical screenings, background checks, status determinations, etc.). Yet CBP refuses to release them. Obviously, if these people were out of CBP custody that would free even more resources to process the rest even faster.

Are other agencies responsible for CBP’s lengthy detention of single adults?

No. About two thirds of the immigrants in CBP custody at any given time are single adults, and they are also the group most likely to be held for an extended period (more than a month). CBP wants to pass off responsibility for these detainees to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the interior enforcement agency responsible for deportations. But the OIG heard that ICE is actually detaining immigrants in some locations at twice its capacity, and overall, ICE has exceeded its capacity by more than 12,000. ICE’s head of Enforcement and Removal Operations Nathalie Asher told OIG that “releasing people on [their own recognizance] is not in [Border Patrol’s] culture but they have the authority; in addition, there is no policy that prohibits them from releasing detainees but they are fine with ICE doing it for them.”

Are other agencies responsible for CBP’s lengthy detention of unaccompanied children?

Partly. The law requires that unaccompanied children be placed with the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within 72 hours. But CBP has decided to separate what it falsely labels “fake families”—almost exclusively non-parental adult family members from children. While the law defines an “unaccompanied” child as someone who enters custody without their “legal guardian,” CBP has adopted the most restrictive definition possible (biological parents only) and refused to exercise its discretion to keep children with family such as siblings, aunts, or grandparents.

Moreover, CBP uses the “exceptional circumstances” exception the TVPRA law to ignore its mandate to transfer to ORR within 72 hours so that it can maintain custody of unaccompanied children (see above) but it refuses to use this same exception to keep children with a responsible family member and release them (which ORR would do anyway). For those who are truly unaccompanied children, conditions would be greatly improved in the short-term by having fewer adults overcrowding CBP facilities, so CBP still receives the bulk of the blame for the truly deplorable conditions that these children find themselves.

However, ORR tells CBP that it will not accept any more unaccompanied children into its overcrowded shelters (even though it’s unclear how those conditions could possibly be worse than those in CBP custody). ORR overcrowding is partly due to CBP separating children from non-parental relatives, but also because ORR decided to exploit the child placement process to help ICE catch and deport illegal immigrants. When illegal immigrant relatives of the children in the United States contact ORR to act as sponsors, ORR would share the information with ICE, which would arrest them. This tactic has caused the number of unaccompanied children in ORR to skyrocket to nearly double the level in 2014, the last time Border Patrol apprehended as many unaccompanied children as it did in May.

Why is CBP holding so many immigrants in inhumane conditions?

Punishment. CBP believes that detention is a deterrent to entering the United States illegally. CBP told the OIG that “they recognize they have a humanitarian issue with detaining single adults for so long, but believe if they do not have a consequence delivery system, either prosecution or ICE detention, the flow will increase.” In other words, they will not release people—even when they are being held in unconstitutional and inhumane conditions—because they feel that would result in more immigrants seeking to come to the United States. This is not Border Patrol’s mission. Border Patrol’s mission is to interdict traffic coming illegally into the country. Its job is not to determine the optimal number of asylum seekers who cross illegally and impose that number by any means necessary.

Will the United States cease to have a border if it releases some apprehended immigrants?

No. Border Patrol Chief Carla Provost told Congress in May that “if there is no consequence, we will lose the border.” U.S. jurisdiction is unaffected by detention or release policies. Moreover, according to Acting DHS Secretary Kevin McAleenan, 70 percent of all border crossers are people not seeking to evade detection. Processing these people—giving them background checks and medical screenings—and then releasing them would probably increase the probability of immigrants turning themselves and make Border Patrol’s job easier.

What should the government do?

It is impossible to list every policy that has led to this moment. But in the immediate term, CBP should stop detaining people in inhumane conditions. It should release anyone else who is not a public safety threat. CBP must immediately stop rejecting asylum seekers at ports of entry. This policy—known as metering—was the reason that Oscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria (who were living homeless in Mexico after repeatedly being rejected at the Brownsville port of entry) attempted to swim across the Rio Grande to the U.S. side, which resulted in them drowning.

CBP at ports of entry can process undocumented immigrants in a matter of minutes for release, which is what they did for Cubans prior to 2017 under its wet foot, dry foot policy. CBP should immediately reinstate wet foot, dry foot for Cubans, taking them out of the detention population and regular asylum process. In the longer term, the United States should focus on expanding legal immigration options for Central America—work permits, family reunification, and refugee resettlement. This would reduce the incentives to come to the U.S. illegally and so better the inhumane conditions the government is forcing immigrants to suffer through today.

Related Tags

Congress Can Recapture 4.5 Million Unused Green Cards

Since 1921, Congress has set hard numerical caps for most types of immigrants coming to the United States on green cards. They have always included uncapped exceptions to green cards for most spouses and minor children of American citizens, but other family-based green card categories and economic or employment-based green cards have had numerical caps based on the category, country of origin, or both since 1921.

During that time, Congress allocated 25,294,990 green cards under the numerically-limited green cards categories, but the government only issued 20,567,754 green cards that counted against those caps. Recapturing all those historically unused green cards, minus the 180,000 green cards recaptured in other legislation, would yield 4,547,236 additional green cards – enough to reduce the entire current green card backlog by 96 percent.

We counted the number of green cards issued annually against the number of green cards available in the capped categories in the historical INS and USCIS documents back to 1922. That year was the first full year in which numerical quotas were applied. We then added the roughly 2.7 million green cards issued after the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act amnesty because they were erroneously counted against the numerically capped categories in some years. Occasionally, more green cards were issued in the capped categories than were allowed, so we subtracted them from the total number that can be recaptured. We also subtracted the 130,000 and 50,000 green cards recaptured in the 2000 American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act and the 2005 REAL ID Act, respectively.

In 72 of the 96 years from 1922 through 2017, when we have data on the number of green cards issued and when the numerical caps were fully in place, the U.S. government has issued fewer green cards than were allocated under the cap. The Great Depression and World War II saw the greatest number of unused green cards – about 1.9 million.

Previous bipartisan bills introduced in recent years have sought to recapture some green cards, but they only go back to the implementation of the Immigration Act of 1990. This proposed recapture is bolder as it goes back to the implementation of the first green card quotas in 1921. As a justification to reduce the green card backlog to a manageable level or to clear it out before replacing the current system as part of comprehensive immigration reform, recapturing over 4.5 million unused green cards from the past would reduce many of the most maddening aspects of the current immigration system.

Special thanks to Sofia Ocampo-Morales for her research for this blog post.

Related Tags

Democratic Debate Ignores Illegal Immigration’s Cause: No Visas

Democratic candidates for president gathered last night to debate, and moderators asked, what would you do to address the number of people crossing illegally? The discussion devolved into the question of whether crossing should remain a crime (punishable by prison time) or just a civil infraction (punishable by deportation). No one stated the obvious: that Congress should make it legal, not to trek through Mexico and swim the Rio Grande, but to board private U.S.-bound airplanes and come to the United States to work.

According to the Department of Homeland Security, the average Central American is paying north of $8,000 to make it to the U.S.-Mexico border where they are brutalized in Mexico and in the United States. Round-trip airfare from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras is under $300. People are dying on the way to make that illegal crossing. When will politicians step up and say clearly, “We think it should be legal to travel to America.”

Sen. Klobuchar came the closest by arguing for the “the economic imperative” to allow immigrant “workers in our fields and in our factories.” But no one made the explicit connection between the availability of visas—which allow noncitizens to board U.S.-bound flights—and illegal crossings. It is not that the civil v. criminal debate isn’t important. It is. But it ignores everything up to the moment where a father makes a fateful decision to jump into a river and cross illegally.

For nearly a century and a half, it was not illegal to travel to the United States (unless you were Chinese after 1882). Immigration restrictions otherwise exlusively focused on criminals, valid public health concerns, and people likely to end up on public welfare. Cato’s first policy analysis on immigration from 1981 argued that the United States should return to this system. The author wrote, “In all the debate over immigration, no one seems to be considering the possibility of returning to America’s traditional open immigration policy.”

The Democratic candidates’ debate has shown how little has changed. The reality of the matter is this. By the end of 2019, nearly 730,000 immigrants from Central America’s Northern Triangle will enter Border Patrol custody. But the U.S. government will issue fewer than 10,000 work visas to nationals of those countries. This disconnect is the cause of the immigration crisis.

Strangely, former-Congressman Beto O’Rourke ended up tacitly defending the continued criminalization of illegal crossing (for anyone except asylum seekers), yet his immigration plan contains the most explicit declaration in support of a free market in international labor. His plan contains a line that states that he would “increase the visa caps so that we match our economic opportunities and needs … to the number of people we allow into this country.” This seems like a round-about way of saying: let supply and demand function in international labor markets. Perhaps he forgot about that part.

The government doesn’t even need to issue visas to everyone who could conceivably want to come in order to resolve this problem. It just needs to issue enough visas that people can see that legal immigration is the easier path in the future than crossing illegally. The goal should be to lower the cost of legal immigration to at least the point that it is less costly to follow that path than to come to the border.

In a piece for The Bulwark last month, I argued that the government should charge immigrants a fee that is less than what they would pay to smugglers to allow migrant workers to come to the United States. This is essentially what the folks at IDEAL Immigration have proposed. This would cover any fiscal costs associated with the immigrants’ arrivals, bankrupt smugglers, and cure the illegal immigration problem.

Such a plan would increase revenues. Yet the bipartisan consensus in the House and Senate right now is to spend billions more on the border detention camps. If immigrants had a viable route to come here legally, U.S. taxpayers wouldn’t need to spend billions every year to fund detention camps, nor would immigrant children be forced to go without toothbrushes and soap while detained. How many more dead children will it take to make politicians decide that this is better?

Related Tags

Higher Asylum Grant Rates Predict Higher Family Appearance Rates in Top Immigration Courts

TRAC Immigration, a project of Syracuse University, published a report this week, showing that 81 percent of recently released families apprehended at the border showed up for all of their hearings. Some immigration court locations did much better than others in obtaining compliance from immigrant families. San Francisco’s court had almost zero no-shows, while two and five skipped out in Atlanta.

TRAC’s report hypothesized that it was possible that “the lowered appearance rates in some courts arose from particular deficiencies in the recording, scheduling or notification systems there.” While this could be, there is no way to test for such variation. Another strong hypothesis, suggested by Aaron Reichlin-Melnik of American Immigration Council, is that immigrants are much more likely to fail to appear in courts where they have a lower probability of receiving asylum.

Fortunately, TRAC also reports asylum grant rates by immigration court, allowing us to test this.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between asylum grant rates in FY 2019 and family appearance rates in the ten immigration courts that received the most family docket cases (in order of the courts with most cases). These ten court were initially designated to track “family unit” cases in November 2018, and while this practice has expanded to several other courts, 87 percent of the family cases tracked by the government are still in these ten courts.

The five courts with the highest appearance rates had asylum grant rates on average 55 percent higher than the five courts with the lowest appearance rates (37 percent to 23 percent). The five most successful courts had 89 percent of their immigrant families appear at all hearings compared to 75 percent at the other five courts.

The asylum grant rate in 2019 predicted a very significant portion of the variance in appearance rates between courts—42 percent to be precise—that year, and a 10 percentage point increase in the asylum grant rate in a court is associated with almost a 3 percentage point increase in the appearance rate for that court. There are other ways to measure the asylum grant rate. The immigration courts include asylum cases that were closed without a decision being made on the merits. But using that metric doesn’t change the association.

Higher failure to appear rates do not explain the higher denial rates, as just 1.4 percent of asylum denials are a result of a failure of the immigrant to appear. People who skip almost always do so before they officially file for asylum. It could be that immigrants who go to certain courts like Atlanta have worse asylum claims to begin with, but as TRAC notes, “there seems little reason for families with different strengths of asylum claims to migrate to some parts of the country and avoid others.”

Ultimately, the identity of the judge seems like the most important factor in winning asylum. The Government Accountability Office in 2016 found that even controlling for other relevant factors, “the defensive asylum grant would vary by 57 percentage points if different immigration judges heard the case of a representative applicant with the same average characteristics we measured.” It would be very useful if TRAC published data on the appearance rates by judge to determine if it’s the location or the judge that matters the most.

Obviously, because we only have data for a few courts in 1 year, it is impossible to nail down this relationship with certainty, but it appears that if every court had the same asylum grant rate as San Francisco (68 percent), the appearance rate for families would have increased to 90 percent. It may seem obvious that the likelihood of success in court makes people more likely to follow the legal process. But many people’s impression is that every asylum applicant has no case, so they have no reason to show up. That’s false, but unfortunately, some courts are turning this theory into a self-fulling prophecy.

Related Tags

Mexico Deported More Central Americans Than the U.S. in 2018

President Trump has decided to blame Mexico for the border crisis, rescinding and then reiterating his threat to impose tariffs on America’s neighbor to the south if it doesn’t stop migrants from Central America’s Northern Triangle from coming. Yet Mexico’s enforcement of immigration laws against Central Americans has been more vigorous than the United States for some time.

In 2018, Mexico deported more immigrants back to the Northern Triangle than the United States did, and it deported nearly all the immigrants who it apprehended in that year. The United States did not. It’s just not true that Mexico is less vigorous in its anti-immigration efforts than the Trump administration.

Indeed, from 2004 to 2018, Mexico deported 1.7 million Central Americans back to the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The comparable U.S. figure was just 1.1 million. As Figure 1 shows, the gap has narrowed in recent years, but in 2018, Mexico still deported 6,177 more Northern Triangle migrants than the United States did in that year. Mexico also deported more in 2015, 2016, and 2017.

The United States is a richer country with a much larger immigrant population from the Northern Triangle than the Mexico (3 million compared to 80,000, according to the United Nations), yet it has still not deported nearly as many as its poorer neighbor to the south.

Moreover, Mexico deported 1.75 million of 1.85 million apprehensions during the same period, meaning that 94 percent of apprehensions are removed (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the United States has routinely apprehended at the border far more Central Americans than it has deported in recent years (Figure 2). The U.S. deported 1.1 million Central Americans from 2004 to 2018, while it apprehended 1.7 million at the border alone (about 10 percent are apprehended in the interior).

President Trump is wrong to blame Mexico for the U.S. inability to enforce its own immigration laws or deter Central Americans. Mexico is carrying out more deportations of Central Americans than the United States is, and it is more likely to deport those who it apprehends than the United States is. The United States should work with Mexico to make legal immigration options more readily available for Central Americans to deter illegal immigration.