The Office of Inspector General (OIG) for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published a report about detention facilities operated by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) yesterday describing “dangerous overcrowding and prolonged detention of children and adults in the Rio Grande Valley.” This report came just over a month after DHS OIG’s May 30 report on “dangerous overcrowding” in El Paso.

What are the conditions in CBP’s detention camps?

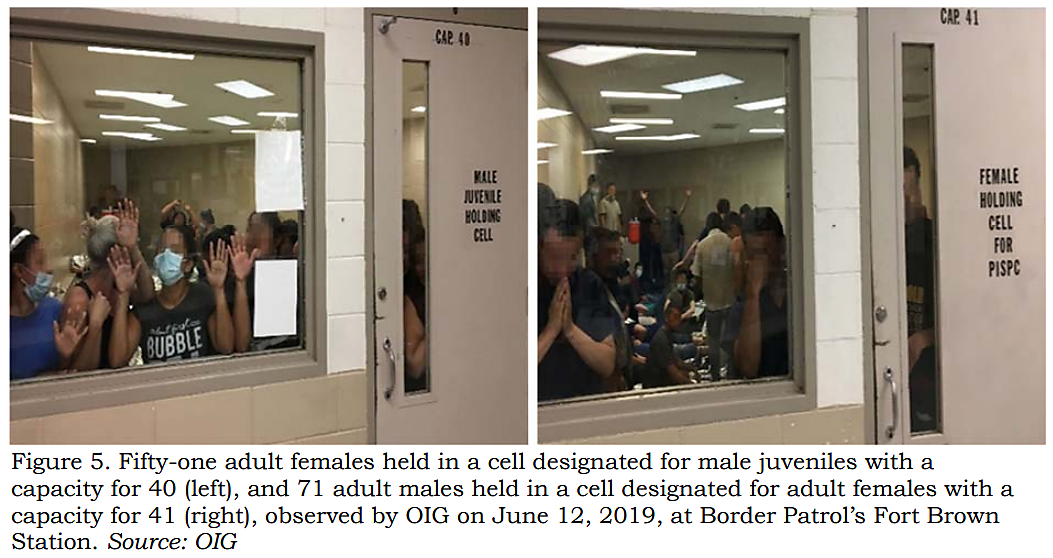

Across the entire border, CBP was detaining from May to June between 4 and 5 times as many people as its facilities were designed to hold. It is impossible to list here everything that the OIG reports exposed, but here are some of what they found:

- A cell with a maximum capacity of 35 held 155 detainees

- A cell with a maximum capacity of 8 held 41 detainees

- Detainees were wearing soiled clothing for days or weeks.

- Children at three of the five Border Patrol facilities visited had no access to showers

- Most single adults had not had a shower in CBP custody despite several being held for as long as a month

- Some single adults were held in standing room only conditions for a week

- Detainees standing on toilets in the cells to make room and gain breathing space, thus limiting access to the toilets

- A diet of only bologna sandwiches. Some detainees on this diet were becoming constipated and required medical attention.

- Standing-room-only conditions for days or weeks.

The OIG found that hundreds of children had been detained in these conditions for more than a week. Dozens of children who were under the age of 7 were held for over 2 weeks. Adults were being caged for a month in unsanitary conditions that were spreading illness. Infamously, the Department of Justice is defending these conditions by arguing that a “safe and sanitary” requirement does not require sleep, toothbrushes, or soap for children. CBP stashed families outside sleeping on the ground under a bridge for days as they were “bombarded with pigeon droppings.” When that was discovered, CBP hid what observers are calling “human dog pounds” elsewhere—again, outside in 100+ degree temperatures.

Other documentation of the depraved treatment elsewhere has come to light. Children told a federal court that infants are being forced to wear “clothing stained with vomit.” Lawyers who inspected the conditions told the New Yorker that during a lice outbreak, Border Patrol had children sharing combs and then when one of these combs was lost, the agents took away their blankets and mats as punishment. A doctor received access to a facility only after a flu outbreak that Border Patrol agents failed to contain had sent five infants to the hospital. Her visit found “extreme cold temperatures, lights on 24 hours a day, no adequate access to medical care, basic sanitation, water, or adequate food.”

Are CBP’s detention conditions a problem?

Yes. CBP has reported the deaths of six children so far this fiscal year after no children had died in the last decade. At least four other adults have also died this fiscal year. Another man committed suicide last year after Border Patrol took away his child and forced him into a detention facility. The conditions are rapidly spreading diseases between detainees, and the OIG found that this was also leading to illnesses among the agents themselves. Border Patrol told the OIG that it believes that holding people in these conditions “could turn violent.” Some agents are even retiring or quitting to avoid the situation. Agents told OIG that the situation is “an immediate risk to the health and safety not just of the detainees, but also DHS agents and officers.”

More fundamentally, the detention conditions are a monstrously unjust way to treat peaceful people. Violent felons and murderers receive better treatment in every state than CBP’s treatment of immigrants and asylum seekers.

Are CBP’s detention conditions violating its own standards?

Yes. CBP’s “Transport, Escort, Detention, and Search” (TEDS) standards provide that showers should normally be provided to children within 48 hours. TEDS standards require children and pregnant women receive at least two hot meals per day and that all detainees not be held in “hold rooms or holding facilities” for more than 72 hours. The OIG found children without any access to a shower at all, even though nearly 30 percent had already passed a 72-hour threshold for release and that they received no hot meals until OIG showed up. It found that the agency also violated a requirement that the fire marshal limit on cell occupancy not be exceeded.

Are CBP’s detention conditions violating the law or the Constitution?

Probably. The William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2008 requires that CBP transfer unaccompanied children (i.e. children without a legal guardian) to shelters run by Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within 72 hours except in “exceptional circumstances.” Moreover, the Flores agreement—which is a court settlement agreement enforced by the District Court for Central California—also requires that all children not be detained for more than 3 days except in the case of an “influx” in which case the standard is “as expeditiously as possible.”

Because immigrants are civil detainees, the 5th amendment of Constitution’s guarantee of protection against punishment without due process of law applies. In this case, given that these conditions are worse than those for convicted criminals or pre-trial detainees, they are definitionally punitive. The American Immigration Council has a lawsuit that may go to trial this Fall to stop these unconstitutional practices.

Is CBP detention legally required?

No. No one appears to disagree with the conclusion that detention is discretionary. Section 212(d)(5)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act grants DHS the authority to “parole”—that is, waive entry restrictions—and allow an immigrant entry to the United States in cases of “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” The dangerous conditions at these Border Patrol stations would easily meet either criteria. The leadership of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—the interior enforcement agency—told the OIG that “if [Border Patrol] feels that they are at a breaking point with managing the masses, [it] has the authority to release” (p. 112). Moreover, CBP itself told the OIG in May that it could process “for immediate release under an order of recognizance.”

Are there security concerns associated with release?

No. The share of criminal aliens apprehended at the border is at an unprecedented low. Despite twice as many apprehensions in 2019, there were half as many criminal aliens. Just 1,214 immigrants apprehended at the border had a criminal conviction for something other than crossing illegally. That is 0.15 percent of all apprehensions this year. These aliens are expeditiously removed from the United States and are not the cause of the overcrowding.

Is the number of immigrants arriving the reason for lengthy CBP detention?

No. The reason that immigrants are languishing for weeks in detention is not a consequence of the daily intake, but the daily output. The OIG found that Border Patrol is “able to complete immigration processing for most detainees within a few days.” At any given time, more than half of all CBP detainees have already completed the CBP intake process (medical screenings, background checks, status determinations, etc.). Yet CBP refuses to release them. Obviously, if these people were out of CBP custody that would free even more resources to process the rest even faster.

Are other agencies responsible for CBP’s lengthy detention of single adults?

No. About two thirds of the immigrants in CBP custody at any given time are single adults, and they are also the group most likely to be held for an extended period (more than a month). CBP wants to pass off responsibility for these detainees to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the interior enforcement agency responsible for deportations. But the OIG heard that ICE is actually detaining immigrants in some locations at twice its capacity, and overall, ICE has exceeded its capacity by more than 12,000. ICE’s head of Enforcement and Removal Operations Nathalie Asher told OIG that “releasing people on [their own recognizance] is not in [Border Patrol’s] culture but they have the authority; in addition, there is no policy that prohibits them from releasing detainees but they are fine with ICE doing it for them.”

Are other agencies responsible for CBP’s lengthy detention of unaccompanied children?

Partly. The law requires that unaccompanied children be placed with the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within 72 hours. But CBP has decided to separate what it falsely labels “fake families”—almost exclusively non-parental adult family members from children. While the law defines an “unaccompanied” child as someone who enters custody without their “legal guardian,” CBP has adopted the most restrictive definition possible (biological parents only) and refused to exercise its discretion to keep children with family such as siblings, aunts, or grandparents.

Moreover, CBP uses the “exceptional circumstances” exception the TVPRA law to ignore its mandate to transfer to ORR within 72 hours so that it can maintain custody of unaccompanied children (see above) but it refuses to use this same exception to keep children with a responsible family member and release them (which ORR would do anyway). For those who are truly unaccompanied children, conditions would be greatly improved in the short-term by having fewer adults overcrowding CBP facilities, so CBP still receives the bulk of the blame for the truly deplorable conditions that these children find themselves.

However, ORR tells CBP that it will not accept any more unaccompanied children into its overcrowded shelters (even though it’s unclear how those conditions could possibly be worse than those in CBP custody). ORR overcrowding is partly due to CBP separating children from non-parental relatives, but also because ORR decided to exploit the child placement process to help ICE catch and deport illegal immigrants. When illegal immigrant relatives of the children in the United States contact ORR to act as sponsors, ORR would share the information with ICE, which would arrest them. This tactic has caused the number of unaccompanied children in ORR to skyrocket to nearly double the level in 2014, the last time Border Patrol apprehended as many unaccompanied children as it did in May.

Why is CBP holding so many immigrants in inhumane conditions?

Punishment. CBP believes that detention is a deterrent to entering the United States illegally. CBP told the OIG that “they recognize they have a humanitarian issue with detaining single adults for so long, but believe if they do not have a consequence delivery system, either prosecution or ICE detention, the flow will increase.” In other words, they will not release people—even when they are being held in unconstitutional and inhumane conditions—because they feel that would result in more immigrants seeking to come to the United States. This is not Border Patrol’s mission. Border Patrol’s mission is to interdict traffic coming illegally into the country. Its job is not to determine the optimal number of asylum seekers who cross illegally and impose that number by any means necessary.

Will the United States cease to have a border if it releases some apprehended immigrants?

No. Border Patrol Chief Carla Provost told Congress in May that “if there is no consequence, we will lose the border.” U.S. jurisdiction is unaffected by detention or release policies. Moreover, according to Acting DHS Secretary Kevin McAleenan, 70 percent of all border crossers are people not seeking to evade detection. Processing these people—giving them background checks and medical screenings—and then releasing them would probably increase the probability of immigrants turning themselves and make Border Patrol’s job easier.

What should the government do?

It is impossible to list every policy that has led to this moment. But in the immediate term, CBP should stop detaining people in inhumane conditions. It should release anyone else who is not a public safety threat. CBP must immediately stop rejecting asylum seekers at ports of entry. This policy—known as metering—was the reason that Oscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria (who were living homeless in Mexico after repeatedly being rejected at the Brownsville port of entry) attempted to swim across the Rio Grande to the U.S. side, which resulted in them drowning.

CBP at ports of entry can process undocumented immigrants in a matter of minutes for release, which is what they did for Cubans prior to 2017 under its wet foot, dry foot policy. CBP should immediately reinstate wet foot, dry foot for Cubans, taking them out of the detention population and regular asylum process. In the longer term, the United States should focus on expanding legal immigration options for Central America—work permits, family reunification, and refugee resettlement. This would reduce the incentives to come to the U.S. illegally and so better the inhumane conditions the government is forcing immigrants to suffer through today.