-

Started in 1995 as the successor to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the now-164-member World Trade Organization (WTO) consists of a baseline set of trade rules (agreements), a negotiating venue for member states, a system for adjudicating member-initiated trade disputes, and a repository for related data and analysis.

-

The WTO itself has a small full-time staff and no decisionmaking powers; its rules, priorities, and activities (including disputes) are determined by member governments alone.

-

The WTO is imperfect and faces real challenges. But most trade experts have long considered it to be a highly effective international organization, free from many of the problems that plague other multilateral institutions such as the United Nations.

-

The WTO remains the subject of many false or misleading claims about its rules, objectives, operations, and biases. The organization is not an aspiring “world government” or “free trade” organization committed to a “neoliberal” agenda; biased against the United States or the developing world; routinely acting outside its mandate; or able to impose its will on member states.

-

WTO rules do not undermine national sovereignty; deny member states “policy space” to address domestic priorities; cause or demand a global “race to the bottom”; or fail to discipline unfair Chinese trade practices or other unfair trade practices in the modern world economy.

-

A proper understanding of these myths and realities is essential to understanding today’s global economy and the real challenges that we face.

In much of the world, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is believed to be a creation of the United States, imposed on other countries—especially poorer ones—through a calculated exercise of the considerable economic leverage intended to force the world to pursue U.S. economic and geopolitical priorities. In this telling, WTO rules are mainly American rules, even though each has been agreed upon by all WTO members in successive rounds of multilateral trade negotiations. These are myths.

The myths in Washington, DC, are much the opposite. There, the WTO is at best a mistake by naïve American diplomats and at worst a “globalist” conspiracy to dictate government policy and reduce U.S. economic might and global influence. A bipartisan majority of lawmakers today see the WTO as bent on undermining U.S. trade laws and unable to discipline China’s hybrid of communism and state capitalism. These claims are also incorrect—but still powerful: the organization has been marginalized in Washington and its rules and rulings ignored, harming the WTO and the member states facing new U.S. trade discrimination, fomenting copycat policies around the world, and in the process, harming the United States itself.

It is therefore imperative that the many myths about the WTO—about it as an institution, about its rules and who makes them, and about how it initiates, adjudicates, and enforces disputes—be once again debunked. This essay begins this process with the most prevalent and damaging WTO myths.

Answering Common Questions about the WTO

Is the WTO Part of a Global Plot to Create a World Government, and Does the United States Have No Choice but to Be a Member of the WTO?

Entirely separate from the United Nations, the WTO is an international economic organization consisting of 164 governments, accounting for about 98 percent of all world commerce and established by an international agreement among those governments. It is a forum for governments to agree by consensus to establish rules that apply to international trade among them and to ensure compliance with those rules when disputes arise between them.

The WTO is a voluntary organization: Every member government is a member by choice, and every member can withdraw from the organization with six months of notice. Members of the U.S. Congress have introduced WTO withdrawal legislation—and former President Donald Trump threatened to withdraw—but it never happened. That no member has ever withdrawn—and that 23 other governments are still trying to join—strongly indicates the economic and geopolitical benefits of WTO membership. Without the shelter and benefits of binding WTO rules and without a neutral venue for peaceful discussion and dispute resolution, the result would be a worldwide return to the pre–World War II free-for-all of discrimination, high trade barriers, retaliation, and opaqueness that decades of WTO multilateral negotiations and agreements have greatly reduced.

Is the WTO a “Free Trade” Organization, and Does It Aim to Fulfill a “Neoliberal” Agenda of Laissez Faire and “free Market Fundamentalism” That Mandates the Removal of All International Barriers to Trade, Mass Deregulation, and a “Race to the Bottom”?

There is nothing in the WTO agreements that requires countries to lower their tariffs and other trade barriers unless they have freely chosen and agreed to do so. Members can decide to lower or eliminate tariffs and other obstacles to trade, or they can decide to keep them. The WTO has long been a multilateral means for achieving freer trade; but this has been because WTO members have long wanted it to serve that purpose. The WTO agreement leaves it to individual countries to set their own trade and other economic policies. As the WTO website explains, “The WTO’s founding Marrakesh Agreement recognizes that trade should be conducted with a view to raising standards of living, ensuring full employment, increasing real income and expanding global trade in goods and services while allowing for the optimal use of the world’s resources.” Very often, achieving this goal means freeing trade; but, in many cases, it can also mean erecting tariffs and other barriers against unfair trade where there is dumping by private companies (basically, selling in the target market at below the cost of production in the home market, with injurious results) or subsidies to private companies or industries by governments that cause injury by distorting the marketplace.

There also is nothing in the WTO agreements that requires the implementation of a worldwide “neoliberal” agenda to eliminate government regulations and social safety nets in service of “free market fundamentalism.” Critics of the WTO talk much about the need for “policy space” reserved for domestic law beyond the reach of international economic rules and often fear that the WTO will overrule local regulations that exceed global standards or promote vital, noncommercial societal values. They warn of tainted “Frankenfoods,” toxic products, diminished labor protections, shrinking public services, and a litany of other public health, safety, and environmental risks.

None of this is true. In fact, the WTO agreements are replete with provisions that assume there will be domestic health, safety, environmental, and other regulations and allow considerably more local policy space than many WTO critics admit. The rules do not address whether national measures—domestic laws, regulations, and practices—are imposed or their stringency but rather how they affect trade. If a measure does not affect trade, then WTO rules are not relevant. If the measure does affect trade, it will be consistent with WTO rules if it provides an equal competitive opportunity in the domestic marketplace for all like foreign and domestic products. Rules on trade in goods generally implicate the sovereign “right to regulate” only where the measure at issue discriminates between and among like traded products, either in favor of domestic over foreign products or in favor of some foreign products over others. Much the same is true in the reservation of policy space under the WTO rules on trade in services.

Similarly, WTO rules require members to protect intellectual property rights but grant considerable latitude to provide such protection “in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare” and “to promote the public interest” through domestic measures that “protect public health and nutrition” and promote “socio-economic and technological development.” Also, WTO rules on technical regulations generally limit local regulations only if they discriminate between and among like traded products, or if they create unnecessary obstacles to international trade or are more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfill a legitimate objective. Rules on “sanitary and phytosanitary” measures permit members to implement measures necessary for the protection of human, animal, or plant life or health, subject to similar conditions and ones regarding the regulations’ scientific basis and the sufficiency of the scientific evidence supporting them.

Given these realities, WTO rules have unsurprisingly not encouraged members to engage in a regulatory “race to the bottom” to attract multinational investment or boost domestic firms’ international competitiveness. In fact, economists have mostly concluded that international trade generally benefits the environment by boosting economic growth, productivity, and innovation and by generating new tax revenues for environmental protection. As economist Jagdish Bhagwati has said, “Efficient policies, such as freer trade, should generally help the environment, not hurt it,” and empirical evidence shows that—over the long term—rising national income results in rising environmental protection.” (Economists call this the “Environmental Kuznets Curve.”) Bhagwati has added, “Eventually environmental degradation peaks. It then begins a steep descent as economy and incomes continue to grow.” There also is “little evidence that polluting industries relocate to jurisdictions with lower environmental standards in order to reduce compliance costs.” The empirical research thus far, as distilled in a study done for the World Bank, “has found little or no evidence that pollution intensive industry is systematically migrating to jurisdictions with weak environmental policy; hence maintaining a weak environmental policy regime appears to have little effect on a country’s comparative advantage. Other factors such as labor productivity, capital abundance, and proximity to markets are much more important in determining firm location and output.” (The World Bank does note that there is more evidence thus far from developed than from developing countries.)

A similar conclusion can be drawn for labor standards over the long term. As American political scientist Daniel Drezner has explained, “There is no indication that the reduction of controls on trade and capital flows has forced a generalized downgrading in labor or environmental conditions. If anything, the opposite has occurred.”

Does the WTO Undermine U.S. Sovereignty or the American Economy?

The WTO does not undermine the sovereignty of the United States or any other member of the WTO. The WTO is frequently called a “member-driven” organization because (in contrast to some other international institutions) its rules and activities are dictated by its member governments alone. The WTO has a legal identity in international law only for the practical purposes of providing office space; retaining employees; purchasing pens, paper, and computers; and keeping the cafeteria open and the windows clean. The WTO has a relatively tiny annual budget of about $220 million, contributed by members based on their proportion of international trade each year. Because the United States has the largest proportion of international trade and thus contributes the most to the WTO budget, it chairs the WTO budget committee, which makes all financial decisions for the organization. Still, the United States contributes a paltry $23.6 million to the WTO’s annual operations, and it does so voluntarily.

About 620 people—mostly economists, lawyers, translators, and administrative staff—work for the WTO members in Geneva, Switzerland; but none of these people can take any action that binds the organization or engage in work other than basic ministerial and administrative tasks. Only the members of the WTO acting together—usually by consensus—can take actions that affect international trade and their government’s obligations under the WTO rules to which they or their predecessors have affirmatively agreed. This compliance is not an undermining of their sovereignty. This is an exercise of their sovereignty; for each of the 164 WTO members has made a sovereign choice that participating in the WTO is in their interest.

The WTO does adjudicate disputes among members but cannot initiate them—complaints must be filed by member governments. The WTO also has no power to enforce its rules or dispute settlement decisions; there is no WTO “police force.” Furthermore, all WTO members—including the United States—can choose to ignore WTO rules and WTO rulings if they wish. That is their sovereign right. As a matter of principle, and consistently with their collective interest in the success of the organization and its rules, no country should exercise this right. However, WTO members—for whatever reason they choose—remain free to ignore WTO rules and rulings, as long as they are willing to accept the loss of previously granted trade concessions as the agreed price for making that choice. This price can sometimes total billions of dollars of lost trade benefits annually, which—along with a desire to maintain the multilateral system and their government’s status therein—has usually proven a strong incentive for WTO members to comply with the rules and the rulings. Noncompliance has thus, until the recent recalcitrance by first the Trump administration and now the Biden administration of the United States, been rare.

It is convenient for politicians to pretend, when complying with a WTO obligation or ruling, that “the WTO” has compelled such action, but this is simply false.

Leaving aside that WTO rules affecting U.S. trade and economic performance have been agreed (and often written) by the U.S. government, or that the United States can (and occasionally does) disregard these rules, there is little evidence that they have harmed the United States—in fact, it’s much the opposite. According to a study by the Bertelsmann Foundation in Germany, for example, WTO membership boosted U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by about $87 billion since the organization began in 1995—more than any other country. Every WTO member from the multilateral trading system has benefited since then; but the United States has benefited more than all the rest. A study commissioned by the U.S.-based Business Roundtable found that international trade supports nearly 41 million American jobs in both goods- and services-producing industries. One in every five American jobs is linked to imports and exports of goods and services. In the first 25 years following the WTO’s establishment, trade-dependent jobs grew more than four times as fast as U.S. jobs generally. Every one of the 50 U.S. states realized net job gains that can be directly attributed to trade. And almost half of all dollars spent on imported goods and services go to American, rather than foreign, workers.

Economists at the Peterson Institute for International Economics have estimated “that the payoff to the United States from trade expansion—stemming from policy liberalization and links to the global economy and improved transportation and communications technology—from 1950 to 2016 [was] roughly $2.1 trillion … [and] that US GDP per capita and GDP per household accordingly increased by $7,014 and $18,131, respectively.” Further, “disproportionate gains probably accrue[d] to poorer households.” One can legitimately debate whether U.S. policy has sufficiently distributed the nation’s considerable gains from WTO membership (and trade), but the gains remain considerable, and the WTO cannot and does not dictate how sovereign governments redistribute them.

Is the WTO Biased against the United States and Other Developed Countries?

Because the WTO is member-driven, the WTO cannot be biased against any member, including the United States. There is to no evidence that new WTO rules or rulings systematically or disproportionately target U.S. policies; but even if there were, this would mean that other countries, not the WTO, are biased against the United States—and that Washington has agreed to accept this bias. The United States is not universally popular with all other countries and has its own biases against certain countries (some justified). Yet, 164 countries of all geopolitical views have agreed to cooperate on trade matters by signing the WTO agreement. The United States has long agreed that such cooperation is necessary. The WTO members can make trade rules that bind all members only by consensus. The United States can, if it wishes, block that consensus; but it can only be bound legally by rules with which it has agreed.

WTO critics allege that the United States and other developed countries suffer because WTO rules are biased against all developed countries and are tilted toward developing countries. Former President Trump voiced this sentiment on Twitter: “The WTO is BROKEN when the world’s RICHEST countries claim to be developing countries to avoid WTO rules and get special treatment. No more!!!” The assumption in this statement is that developing countries are profiting from being in the WTO while developed countries are not.

The aforementioned economic analyses refute this conclusion, as does even a rudimentary understanding of the WTO rules applicable to developing countries. The 47 countries with less than $1,025 in per capita income—“least-developed countries”—are generally given “special and differential treatment” that can excuse them from certain WTO rules. Economists know that these exceptions are not in the least-developed countries’ own economic interest, but because their economies are relatively small, little economic harm befalls the United States because of them. Meanwhile, developing countries at higher stages of development—including large economies such as China, Brazil, and India—still claim to be entitled to certain special and differential treatment provisions, but they derive little benefit from such treatment. For one thing, the exceptions themselves are relatively minor in terms of their legal and economic significance. More important, and as Inu Manak and I concluded in The Development Dimension, special and differential treatment “is based on the premise that the growth of developing countries will be hastened if they postpone opening their markets to freer trade for as long as they can.” The opposite is true.

Does the WTO Offer No Remedies for the Trade and Other Commercial Abuses of the “State Capitalism” of China and for Unfair Trade Practices in Many Areas of the New “21st Century” Economy?

China’s economic rise poses a unique challenge to the world trading system, but WTO dispute settlement has more potential to address China’s practices than most U.S. politicians and pundits understand. Indeed, the United States could today file a lengthy list of legal challenges to an array of Chinese trade practices under existing WTO rules, including on intellectual property protection and enforcement; trade secrets protection; forced technology transfer; and subsidies. The unfortunate reality is that, for the most part, the United States and like-minded members have not filed these challenges. Furthermore, the WTO—as a member-driven organization—cannot unilaterally initiate or adjudicate them. The failure to bring these potential legal claims against China is particularly disappointing, given that China does not—also contrary to myth—routinely ignore adverse WTO rulings; in fact, given recent U.S. foot-dragging, China may have a better record of complying with adverse WTO rulings than the United States.

This is not to say that current WTO rules should not be improved or that new WTO rules should not be negotiated and agreed to help counter the unique challenge posed by China to the multilateral trading system. They should be. But the means of accomplishing this (admittedly difficult) end is not by ignoring the WTO and WTO rules; it is by employing those rules in dispute settlement and by giving priority to negotiating new and improved rules within the WTO.

Does WTO Dispute Settlement Discriminate against the United States?

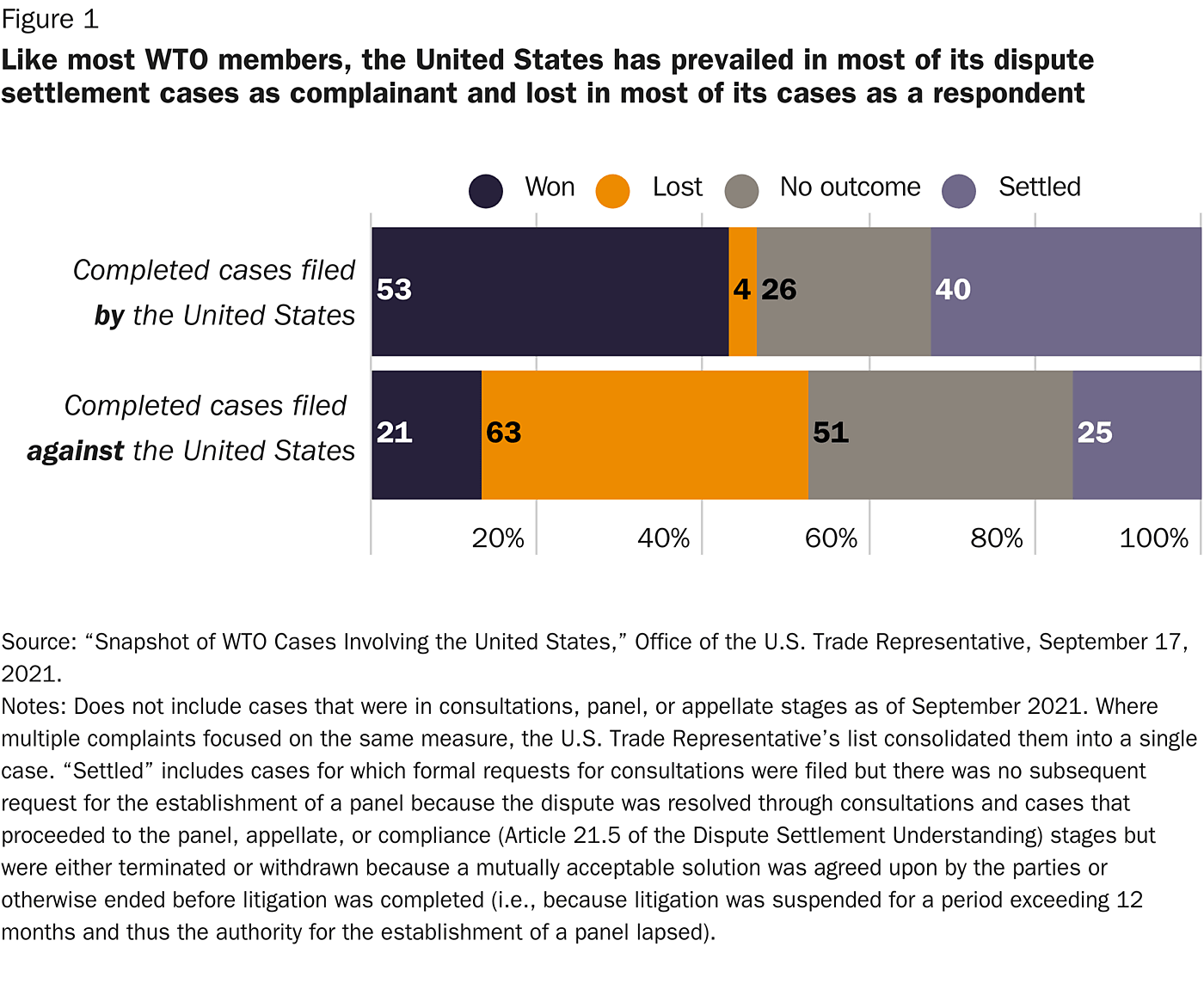

According to President Trump, “We lose … almost all the lawsuits in the WTO,” and U.S. policymakers often agree with him that WTO jurists are biased against the United States. In reality, however, the United States has won the vast majority of the cases it has brought as a complainant in WTO dispute settlement (including the overwhelming majority of the cases it has brought against China) and has the best success record of any complainant. By contrast, the United States has lost most of the cases that have been brought against it in WTO dispute settlement, including a series of cases relating to the use of trade remedies in which the United States has lost mainly because it has been recalcitrant in complying with previous adverse rulings on the same or similar legal issues. Figure 1 below displays these facts.

Much of this reflects institutional dynamics: Out of more than 600 international trade disputes so far, complaining countries have won about 90 percent of the cases they have taken to WTO dispute settlement. Countries tend not to undertake the laborious task of filing a complaint against another country in WTO dispute settlement, with all the costs and geopolitical consequences that sometimes result, unless they believe they have a strong legal case that can be made.

However, some of the United States’ record in dispute settlement is of its own choosing. Many of the cases the United States has lost have involved the expansive American use of anti-dumping duties, countervailing duties to governmental subsidies, and other trade retaliations that are generally known as “trade remedies.” In these cases, the United States pushed beyond the legal boundaries of WTO rules for applying such trade restrictions—rules that the U.S. government negotiated and with which it agreed when the WTO was established. And when the United States lost these disputes, it did not reform the laws and practices at fault (an exercise of national sovereignty), thus resulting in more disputes on the same legal issues and more U.S. losses.

There also is no evidence of WTO jurists—many of whom are American—being biased against the United States, regardless of their nationality. Jurists do not serve any one country; they serve the multilateral trading system. Toward this end, they shed their nationality when they become WTO jurists. According to the WTO Rules of Conduct, WTO jurists “shall be independent and impartial” and “shall avoid direct or indirect conflicts of interest,” among other requirements designed to safeguard “the integrity and impartiality” of the dispute settlement system. In the more than a quarter of a century since the establishment of the WTO and the adoption of these rules of conduct, the United States has brought not one claim contending that a WTO jurist is not “independent and impartial” or has a “direct or indirect conflict of interest.” Allegations of jurist bias—often after losing a dispute—are politics and nothing more.

Do WTO Jurists Routinely Exceed Their Authority under the WTO Agreement?

No. The Trump and Biden administrations have blocked the seating of new members of the WTO Appellate Body, which handles appeals of lower dispute panel decisions, on the grounds that Appellate Body members have routinely exceeded their authority under the WTO agreement. The Appellate Body members are said to have frequently engaged in “overreaching” and in “gap filling” that have altered the obligations in the WTO agreement, which is in direct violation of their own obligations in that agreement.

This claim, however, is simply not true. Like any tribunal, the Appellate Body is comprised of imperfect jurists who can occasionally get discrete points wrong. So can the Supreme Court of the United States. But, contrary to the U.S. portrayal, the Appellate Body is actually doing its job properly as mandated in the WTO agreement. In particular, WTO members—including the United States—have instructed WTO jurists to “clarify the existing provisions” of the various trade agreements that altogether comprise the WTO agreement “in accordance with customary rules of interpretation of public international law.” Those customary rules require that a treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose. (These customary rules of treaty interpretation are expressed in Article 31 and Article 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties; however, as customary rules, they exist independently of that convention as international law.) Thus, the members of the Appellate Body are tasked with clarifying the meaning of the provisions in the WTO agreement in accordance with these rules. This is not “overreaching” or “gap-filling.” It is simply the Appellate Body doing what the members of the WTO have told it to do in the WTO agreement.

If, in fulfilling its mandate, the Appellate Body makes a mistake in doing its job by reaching the wrong result in its clarification, then there is a ready remedy. The members can overrule the Appellate Body’s ruling by adopting their own legal interpretation, which will be binding on all WTO jurists. This would take a vote of a “three-fourths majority of the Members.” So far, the United States has not sought to invoke this provision to overturn a single Appellate Body ruling. This inaction is, again, telling.

Conclusion

For the sake of brevity, this essay addresses only the most pervasive myths about the WTO. There are more, and new myths seem to emerge almost daily. Such fallacies may help those who wish to promote their own political or economic agendas at the expense of the continued functioning of the WTO as a global public good, but they imperil reforms that would help improve the multilateral trading system and accomplish its long-standing goals of peace and prosperity through trade. Dispelling them can help to restore the WTO to its rightful place at the center of world trade and of world trade policy and decisionmaking. It is long past time, in the United States especially, to tell the truth about the WTO.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.