-

Corporations and other interest groups, along with flawed economic thinking, create strong demand for protectionism, and therefore the ideal of unilateral free trade is difficult to achieve.

-

Free trade is simple in theory but complicated in practice, and trade agreements are necessary to flesh out the details.

-

While corporations/interest groups have had success in getting some of their demands inserted into trade agreements, on balance, trade agreements promote liberalization and competition through commitments to lower protectionist trade barriers.

-

Trade agreements promote the rule of law in international affairs and act as a check on unilateralism and trade wars.

Imagine a world with two countries in which the people and the political leaders believe in free trade: Cobdenia and Friedmania. Neither country would impose tariffs on imports from the other, and products that could legally be sold in one could also be sold in the other. There would be no need for a trade agreement in this situation, although just to emphasize their point of view, the two countries could sign a one-page agreement that said something along the lines of “the current state of free trade between the two countries shall continue.”

The real world, of course, is messier. Many domestic corporations and labor unions object to the competition with foreign companies that free trade would bring. And some people and politicians genuinely do not believe that free trade is good policy, arguing that protectionism is the way to wealth and prosperity. The result has been a trading system characterized by continued protectionism, with trade agreements used as a second-best way to liberalize trade and constrain protectionism. These agreements achieve some liberalization but do not come close to full free trade. And in recent years, interest groups have used them to push for policies outside of the core free trade versus protectionism debate, some of which may restrict trade more than they promote it.

For these reasons, trade agreements are not a perfect way to achieve their goals. And as a result, they have been subject to criticism from some free traders, who say something along the lines of, “why can’t we just have a one-page free trade agreement?” These agreements have also been criticized as corporate rent-seeking tools. In this view, trade agreements are simply tools for powerful corporations to receive special treatment that will increase their profits.

The criticisms are mostly misguided. Over the last few decades, trade agreements have reduced protectionism and have created a rules-based system that keeps trade wars in check. And on balance, albeit with some exceptions, they have helped keep corporate demands for government favors at bay. The thousands of pages of trade agreements have helped shift the world in the direction of free trade and have reduced corporate influence over government policymaking.

This paper explains the key aspects of trade agreements as follows. The free trade part of trade agreements has three components: Commitments to keep protectionism within agreed upon levels; clarifications related to how to identify protectionism in domestic laws and regulations; and an enforcement mechanism to help ensure compliance with these commitments and rules. The non–free trade part includes international obligations in a wide range of policy areas, mostly related to corporate demands or social policy advocated by civil society groups. Each of these aspects of trade agreements is elaborated below.

Trade Agreements Bring Us Freer Trade

As Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman observed decades ago, trade agreements would be unnecessary in a world run by economists because national governments would eliminate their trade barriers without regard to what other nations did:

The economist’s case for free trade is essentially a unilateral case—that is, it says that a country serves its own interests by pursuing free trade regardless of what other countries may do. Or as Frederic Bastiat put it, it makes no more sense to be protectionist because other countries have tariffs than it would to block up our harbors because other countries have rocky coasts. So if our theories really held sway, there would be no need for trade treaties: global free trade would emerge spontaneously from the unrestricted pursuit of national interest.

However, Krugman added, “the world is not ruled by economists”; it is run by politicians—ones who, in practice, will usually pursue beneficial market-opening “in return for comparable market-opening on the part of their trading partners.” Reciprocal trade agreements have therefore become the primary means by which democratic governments liberalize trade across their national borders.

The mercantilist framing of trade agreements’ reciprocity model—where market access (e.g., tariff reduction) is a “concession” only to be traded for another nation’s liberalization—supports the fallacy that exports are good, imports are bad, and the trade balance is the “scorecard.” That fallacy lies at the root of public skepticism about free trade and allows trade skeptics to paint a free trade agreement as a “failure” if imports increase more than exports following the agreement’s implementation. The diplomatic origins of the reciprocity model also have ensured that trade liberalization is treated as a foreign, rather than domestic, policy area in which negotiations take on a zero-sum, warlike mentality where benefits are “won” or “lost,” instead of mutually achieved. Thus, free trade agreements can, over the long term, sow the ideological seeds of their own destruction. Nevertheless, as explained below, trade agreements are a practical way forward on trade liberalization given existing political constraints. Trade agreements promote trade liberalization in three main ways (beyond convincing politicians to get on board): 1) They include mutually agreed upon commitments to limit discrimination and protectionism; 2) they define what free trade means in the context of specific categories of government policies; and 3) they have an enforcement mechanism that provides for adjudication of disagreements about governments’ protectionist measures, which helps avoid unilateral action and trade wars.

Specific Commitments to Reduce Discrimination and Protectionism

One of the most important functions of trade agreements is to set limits on the use of protectionism, via reciprocal, market-opening commitments (or “concessions”). While this mercantilist approach falls short of economists’ unilateral free trade ideal, it is a practical, incremental approach that moves trade policy in the direction of trade liberalization by balancing the interests of one politically influential group—the farmers, manufacturers, and service providers who want access to foreign markets—against those of the politically influential entities that want government protection from import competition.

Trade agreement commitments apply to several types of measures: ordinary tariffs on trade in goods, restrictions on trade in services, government procurement requirements, and agriculture subsidies. For each, governments commit, in trade agreement “schedules,” to limit how much protectionism each will employ.

Tariffs are the easiest to understand. Except for Chile, which has a uniform tariff that applies to all products, governments have complicated domestic tariff schedules that apply different tariff rates to specific products. This approach lets governments generally liberalize trade while still protecting certain politically sensitive products sold domestically by influential companies or individuals (e.g., Florida sugar farmers). As a result, trade agreements contain long schedules that set out maximum tariff rates for each product, at a detailed level. For example, the maximum tariff rate for one kind of steel might be 10 percent, while the maximum rate for another steel product would be 5 percent.

These scheduled tariff commitments are established through negotiations. Country X might want to sell cars to Country Y, and Country Y might want to sell beer to Country X. In the negotiation, there are a series of requests and offers, the result of which is that each one agrees to lower the tariff on the product the other wants to sell. Importantly, in a multilateral negotiation at the World Trade Organization (WTO), the lower tariff would be granted to all 164 countries on a nondiscriminatory basis, thus amplifying multilateral deals’ trade liberalizing effects versus bilateral or regional ones.

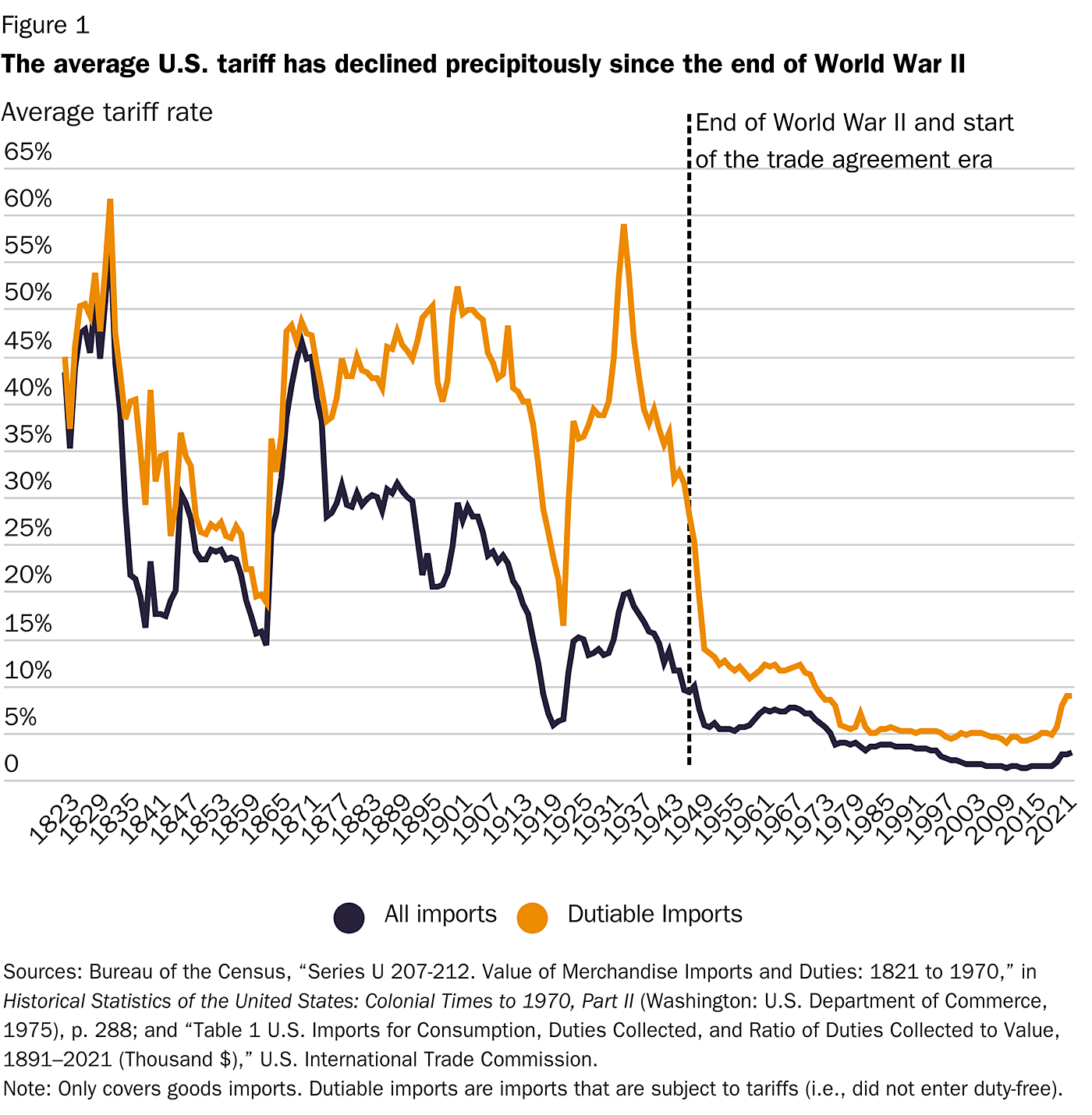

Though this approach is complicated and unsatisfying to purists, it has nevertheless been successful: tariffs have declined considerably over the years. For example, economists estimate that the WTO’s predecessor agreement, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, reduced average tariffs on the world’s industrial goods to less than 5 percent in 1993 from between 22 percent and 40 percent when the agreement took effect in 1947. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), meanwhile, brought ordinary tariffs on trade between Canada, Mexico, and the United States to zero. Figure 1 shows a steep decline in U.S. tariff levels in the trade agreement era that began after World War II.

For services, trade rules are more complicated because services are supplied via four different “modes”: 1) cross-border supply; 2) consumption abroad; 3) commercial presence; and 4) presence of natural persons. For example, an American might go abroad to Thailand for cheaper medical treatment (mode 2), or a Canadian bank might open a branch in the United States to serve American customers (mode 3). Unlike goods, border measures imposed on services at customs entry points are not much of an issue. Rather, trade talks focus on domestic regulations that affect foreign services, and trade agreement services schedules involve detailed commitments for the trade in a particular type of service (e.g., medical services, financial services), with commitments that vary by mode of supply.

On procurement, governments make commitments in trade agreements to open the procurement of specific domestic government agencies to foreign competition. “Buy national” programs such as Buy America are common and show that government contracting still involves a good deal of protectionism. However, governments do make commitments to open the bidding on certain government contracts to foreign competition, and trade agreements promote free trade in the goods and services that covered agencies buy.

Finally, in the WTO’s Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, governments made specific commitments on agriculture subsidies, thus agreeing to limit the amount of financial assistance they would provide to their domestic farmers. Subsidies can distort trade by giving an advantage to domestic companies over their foreign competitors, both in the domestic market and sales abroad. They also can undermine support for trade liberalization among companies and individuals who compete against subsidized foreign counterparts. In the Uruguay Round, governments agreed to limit subsidies considered to be particularly trade distorting. Some limits were set at high levels, but establishing a cap nevertheless prevented governments from substantially increasing subsidies even further.

Because these commitments are so detailed, in terms of specific goods, services, procurement entities, and agricultural subsidies, trade agreements take up thousands of pages to achieve their trade-liberalizing objectives. Their length has led some to criticize trade agreements and suspect that they contain hidden special-interest favors. Some of this cronyism doubtless exists, but make no mistake: the agreements’ scheduled commitments shift national trade policies toward freer trade and actually check special interest demands for government protection from foreign competition.

Defining Free Trade

“Free trade” sounds simple but can be quite complicated in practice. For starters, domestic regulations may have non-protectionist policy objectives yet still disproportionally affect foreign goods, thus raising trade concerns. To address this issue, numerous trade agreement provisions define and clarify the boundaries of what agreements require for domestic regulations that affect foreign goods and services.

Most notably, the core WTO principle of “national treatment” sets out the boundaries for when taxes and regulations on goods constitute “disguised” protectionism, as well as for trade in services where commitments have been made. And for specific subcategories of measures, such as product regulations and food safety measures, there are more detailed definitions. And finally, there are exceptions that provide that measures taken for specific social policy reasons can be justified even if they would otherwise violate the rules. These basic rules establish when domestic laws and regulations are contrary to free trade principles.

These rules also help clarify the use of regulatory standards that differ across countries. Regulatory differences can burden trade, but regulatory experimentation can be a good thing, and governments have a general “right to regulate.” Some would argue that if a product can legally be sold in one country, it should be legal to sell it in another. But if you think of the example of marijuana, it is easy to see why someone might object to this high level of economic integration. Different values and levels of risk tolerance, among other things, could lead governments to diverge in their regulations and want to apply those differences to imports as well as their own domestic products. Trade agreements thus recognize governments’ regulatory autonomy and diversity but also establish rules for when domestic regulations cross the line into costly, “disguised” protectionism.

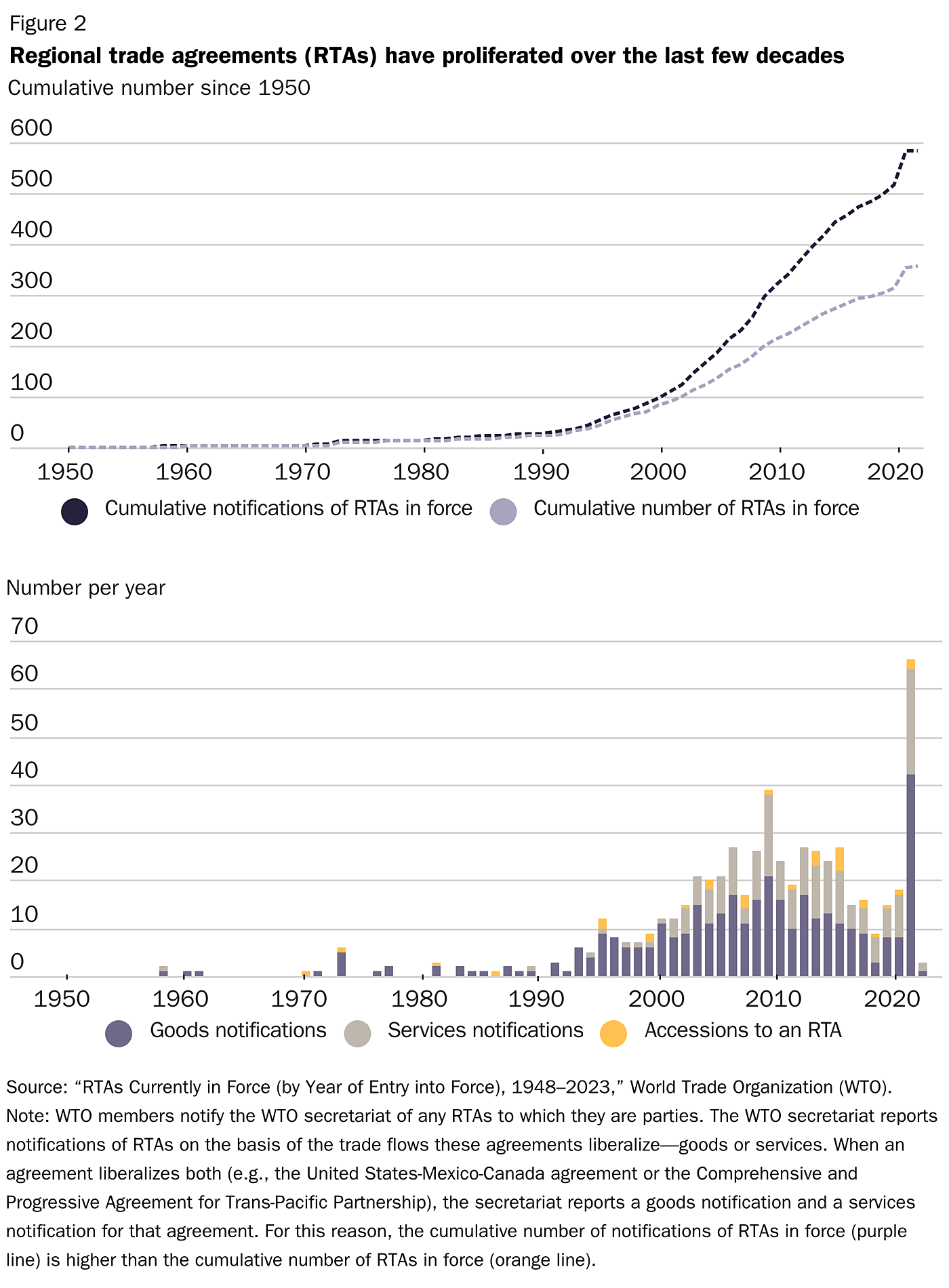

Second, the relatively recent proliferation of bilateral and regional “free trade” agreements (Figure 2) has created a spaghetti bowl trading system full of agreements that connect individual nations.

At the WTO, multilateral rules govern these agreements, defining when and how a small number of the 164 member governments may carve out a deeper, more integrated free trade area within the larger trading system. While called “free trade agreements,” bilateral and regional deals can actually be trade distorting rather than trade creating. WTO rules thus govern how these trade agreements operate to ensure that they create trade more than they distort it. Without rules in this area, these “free trade” agreements could do more harm than good.

Beyond these general principles, trade agreements also have some detailed rules that address how parties may apply specific types of trade measures to ensure that they are not being abused for protectionist purposes. For example, trade agreements do the following:

- They discipline how governments can collect tariffs. In calculating the tariffs to be collected for a specific shipment of imported goods, governments must take actions such as determining the country of origin, the customs category of the good, and the good’s value. Trade agreements contain detailed rules that guide this process and ensure that governments do not impose more tariffs than they should.

- They discipline special tariffs called “trade remedies”—antidumping duties, countervailing duties, and safeguards (safeguards also can be implemented through quotas). Rules on antidumping allow tariffs to be imposed on imports that are sold at prices deemed to be too low (e.g., below costs or below the price for which they are sold in their domestic market)—a pricing practice that some argue indicates “predatory” behavior by a foreign exporter. Countervailing duties may be imposed when imported goods are subsidized by the home government, giving them an “unfair” advantage in a certain export market. And safeguards are designed to respond to a surge of fairly traded imports and to give a domestic industry a fixed amount of time to adjust to this new competition. Some supporters of trade remedy measures justify them on the ground that, while they restrict imports, they are necessary to induce governments to implement a trade agreement’s much broader liberalization by ensuring that they can protect politically powerful domestic interest groups (e.g., steel companies and workers) from “unfair” or overwhelming import competition. However, trade remedies are manifestly protectionist and have been subject to widespread criticism that many countries, including the United States, abuse these measures. WTO rules thus set detailed disciplines on these measures to limit abuse, and trade remedy measures are among the most common dispute settlement subjects.

- They classify subsidies that are particularly trade distorting in a special category that is subject to harsher punishment. In this regard, subsidies tied to export and to the use of domestic content are deemed “prohibited.” The WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures has detailed definitions of the measures that fall into this category.

Through the definitions and obligations described above (and others), trade agreements establish the boundaries of what measures are protectionist and try to prevent certain measures from being abused for protectionist or discriminatory ends.

Enforcement

Trade agreement rules would be of little value if they could not be enforced. In many areas of international law, when one government complains about another’s behavior, there are no effective remedies. But international trade agreements have well-developed procedures that have been at the forefront of international dispute settlement, and they have “teeth” in the form of penalties—the loss of certain trade benefits that the agreement confers—in case of noncompliance. Governments file complaints under a dispute settlement mechanism that relies on impartial tribunals, whose decisions have been relatively effective at inducing the losing government to reform an offending trade measure, usually without the imposition of any actual penalties (e.g., new tariffs on a losing government’s exports to the winning government’s markets). This compliance is voluntary, in that the WTO (or other trade agreement body) cannot force a member government to remove an offending trade measure; it can only authorize a winning government to suspend certain trade benefits that membership in an agreement guarantees a losing member. Nevertheless, governments usually comply, because of the potential impact of this suspension, as well as the value governments place on the overall trading system (which would be undermined by frequent noncompliance) or, at least, the public perception of them supporting it.

While governments have refused to comply with a handful of adverse decisions, and in recent years the U.S. government has taken actions that have undermined the WTO’s dispute settlement system, the system still stands out as one of the most effective in international law.

The WTO system acts as an important check on unilateral protectionism and reduces the chances of a full-blown trade war. Prior to the WTO’s creation in 1995, the U.S. government frequently invoked Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to investigate, prosecute, and judge whether a foreign government was doing something “unfair” and then impose tariffs or other measures to address any “unfair” trade practice. This approach could lead to retaliation by the foreign government, and in practice, the approach has rarely induced governments to change their policies.

By contrast, modern trade agreements rely on neutral adjudication to resolve trade disputes among member governments. The agreements contain detailed obligations, require a member government to bring a complaint instead of acting unilaterally, and authorize independent adjudicators to hear those complaints, apply the rules, and authorize retaliation in the event of noncompliance. This approach reduces the possibility of retaliation because the adjudicators’ decision is seen as a neutral and objective one, unlike the unilateral determinations of governments. A government’s trade retaliation can be used to induce compliance, but the level of retaliation is set by independent arbitrators rather than the complaining governments. And, as noted above, actual trade retaliation is rare—in part because it harms the retaliating nation too. This approach reduces the role of politics in trade disputes and brings rules and order to trade conflicts that arise.

In such a system, it is important that obligations be spelled out precisely, or else governments will think they have the flexibility to make creative arguments that they are in compliance with those rules. Vague rules can thus lead to more trade conflict, as governments decide it is worth seeing if they can convince adjudicators that their policies are not in violation. They also can put adjudicators in a difficult position of filling gaps in the rules or letting member governments get away with obvious violations of the spirit. More specific and detailed trade agreement rules, which take up more pages, can help prevent these scenarios, which can undermine the agreement and the trade that it facilitates.

Some Trade Agreement Provisions Can Actually Discourage Trade

Although the core aspects of trade agreements described above are not true “free trade” but are still generally trade liberalizing, two aspects of these agreements are not about trade liberalization at all and could actually discourage trade: (1) efforts by corporations to lobby for special rules that benefit them and (2) efforts by civil society groups to lobby for social policy regulations.

As an example of pro-business lobbying, in the Trans Pacific Partnership talks, one controversial issue was the promotion of a long term of data exclusivity after the approval of biologic drugs. The United States already has a long term for this in domestic law, and the idea was to push other governments to change their own domestic policies in this direction by having an international agreement require it.

Some interest groups have pushed successfully for regulations on labor rights and environmental protection. These rules were first included in the NAFTA through a side agreement but were later brought into the main text of trade agreements and were made subject to the regular dispute provisions. Over time, the substantive protections were broadened as well. The initial rules in this area made clear that only labor and environmental measures that affected trade were covered. For example, the Dominican Republic-Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), signed in 2006, uses the following language: “A Party shall not fail to effectively enforce its labor laws, through a sustained or recurring course of action or inaction, in a manner affecting trade between the Parties, after the date of entry into force of this Agreement.” However, after a CAFTA-DR panel rejected a U.S. claim that Guatemala was not acting consistently with its obligations under the labor chapter, the language was tweaked in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to loosen this requirement in a number of ways, including the establishment of a presumption that a failure to comply with the USMCA’s labor obligations affects trade or investment.

Do these policies belong in trade agreements? Are the trade agreement provisions in these areas effective at achieving the policy goals? For each issue, there is a debate on the merits of the policy and how best to pursue it, but this debate looks very different from the free trade versus protectionism debate, and it is not clear how well these rules fit into trade policy.

Conclusion

One of the complaints about trade agreements is that they are corporate-dominated exercises that ignore ordinary workers. In reality, however, the core anti-protectionism aspect of trade agreements acts as a check on corporate power. Companies lobby governments to protect them from foreign competition, asking for tariffs, subsidies, Buy National procurement requirements, and other government interventions to limit competition and increase profits above market levels. Trade agreements constrain governments’ ability to do these political favors for corporations and in this way should be seen mainly as an anti-corporate power exercise.

At the same time, it is true that corporations and other interest groups have found ways to insert their demands into trade negotiations, just as they do in domestic legislation. When interest groups see that law is being made through a particular method, they look for ways to take advantage of it.

This feature of trade agreements means that they are not perfect, but compromise and incremental gains are the way the world works in practice. In all policy areas, there is a debate over how idealist or practical to be. Should we go for everything we want? Or should we compromise and take what we can get? In trade policy, trade agreements are a compromise. They move policy a bit toward the free trade side by reining in protectionism to some extent.

To get to a state of affairs where free trade can be set out in one-page trade agreements, supporters need to win hearts and minds first. They have the majority of economists, but that’s not enough. They need to convince the voters and find a way to beat back the special interests. Until that happens, we are stuck with the second-best solution of long, complex, and sometimes convoluted trade agreements that make progress but, admittedly, leave room for improvement.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.