-

Western scholars and policymakers used to think of economic interdependence as an unalloyed good; in recent years, however, it has been viewed as something that could be weaponized.

-

Economic interdependence is hardly a cure-all for U.S. national security concerns, but it also is not the acute national security threat that is commonly articulated inside the Beltway.

-

Fears of malevolent interdependence can be self-fulfilling—if policymakers continue to view globalization as a threat, then the collective policy responses will increase the likelihood of great power conflict.

The liberal internationalism that guided American foreign policy throughout the post–Cold War era rested on multiple pillars: democracy promotion, expansion of human rights protections, bolstering global governance structures, and so forth. One of the most important elements, however, was making globalization truly global. By the mid-1980s, trade barriers and capital controls had been reduced within the first world. A central goal of the European Union was to bind France and Germany so closely together that the idea of going to war again seemed ludicrous. A key logic behind the North American Free Trade Agreement was for the United States and Mexico to end centuries of enmity by expanding trade across the border.

The end of the Cold War discredited the development strategies of central planning as well as import substitution and industrialization. These failures buoyed advocates of the “Washington Consensus” to promote neoliberal policies as a template for transition economies as well as the Global South. These ideas diffused through the rest of the world in the 1990s. Neoliberalism was easier to advance as the United States encouraged developing and transition economies to join the Bretton Woods Institutions: the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization (WTO), the successor to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The GATT had fewer than 100 members as the Cold War was ending. By the end of 2000, an institutionally stronger WTO had added an additional 45 members, with China’s 2001 entrance entering final negotiations.

All of this was consistent with the tenets of liberal internationalism. Long before Adam Smith argued that free trade was economically beneficial, advocates for freer trade viewed international exchange as a means of reducing the risk of war. As far back as Norman Angell’s pre–World War I pamphlets, scholars had argued that the gains from trade far outweighed the gains of plunder. A more open economy would therefore reward productive entrepreneurship far more than destructive entrepreneurship. The modern version of this argument came from political scientists Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, who argued in Power and Interdependence that “networks of interdependence” would constrain the use of force across most issue areas.

During the post–Cold War era, both scholars and policymakers embraced this view of interdependence. Since 2016, however, there has been a sea change in elite attitudes about the costs and benefits of economic interdependence. In 2019, Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman published a blockbuster paper in International Security pointing out that networked economic structures—such as global supply chains, energy pipelines, and capital markets—created interdependencies that state actors could weaponize. Soon, everyone inside the Beltway had embraced the idea. In Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology (p. 317), Christopher Miller quoted one U.S. official saying, “weaponized interdependence, it’s a beautiful thing.” The result has been widespread predictions of “deglobalization.”

The new security fears about interdependence meshed nicely with policymakers searching for a post-neoliberal worldview. This search was rooted in part by an economic conviction that neoliberal economic policies had enriched China and the 1 percent on the backs of America’s working class—a hypothesis that goes beyond the scope of this essay and is addressed by others in this series. It was also rooted by the perception that multiple recent shocks had exposed the folly of excessive interdependence. The coronavirus pandemic seemingly confirmed the risks of relying on other countries for vital supply chains. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its weaponization of energy pipelines to Europe have highlighted the risk of weaponized interdependence.

This essay stands athwart this paranoia about malevolent forms of interdependence and yells, “stop!” Economic interdependence is hardly a cure-all for U.S. national security concerns, but it also is not the acute national security threat that is commonly articulated inside the Beltway. Concerns have been greatly exaggerated, while the geopolitical benefits of interdependence have been underestimated. Even in 2023, China’s interdependence with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development economies has acted as a constraint on its foreign policy behavior. Indeed, the Biden administration seems belatedly aware that it has stigmatized trade with China a bit too much. If current trends persist, however, the United States risks further geoeconomic fragmentation—and the loosening of those constraints. The worldview of malevolent interdependence is likely wrong, but those fears can be self-fulfilling. In other words, if policymakers continue to view globalization as a threat, then the combined policy responses are likely to increase the likelihood of great power conflict.

How Could Economic Interdependence Affect World Politics?

The liberal paradigm in international relations (not to be confused with how the word “liberal” is used in the left-right distinctions of American politics) rests on a “Kantian triad” of interlocking forces designed to prevent the anarchic nature of world politics from spilling over into violent conflict. It was believed that a world of democratic states, international organizations, and economic interdependence would lead to a pluralistic security community in which no state would have the incentive to start a war. Within Kant’s own writings, it is true that the economic interdependence plank was the weakest of the three. Modern scholars, however, have argued that the logic of commercial peace is as strong or stronger than that of democratic peace.

Commercial peace between nations operates through multiple causal mechanisms. The simplest one is at the individual level: in trading states, ambitious individuals will flock to the commercial sector rather than the security sector, thereby taming man’s passions and converting them into economic self-interest. At the domestic political level, the growth of trade between countries also creates interest groups on both sides with a vested interest in maintaining harmonious bilateral relations. At the level of the international system, commercial peace operates by a simple rational choice: state leaders will be wary of the loss of wealth that would come with a war against a trading partner. These logics are not mutually exclusive but rather reinforcing—and all of them contribute to the power of commercial peace.

Some liberal scholars have gone even further. Keohane and Nye argued that complex interdependence would drastically reduce the utility of force in world politics. Erik Gartzke argued that capitalist peace is so powerful that it is the primary driver behind democratic peace. Gartzke suggested that the spread of market forces reduces violence for multiple reasons, including that “the historic impetus to territorial expansion is tempered by the rising importance of intellectual and financial capital” and that “the rise of global capital markets creates a new mechanism for competition and communication for states that might otherwise be forced to fight.” He is hardly the only scholar to advance this argument. More popular proponents, like Thomas L. Friedman, argued that globalization was so powerful that it flattened many power differentials that existed in the world.

There have always been counterarguments to commercial peace within the scholarly literature. Even as the liberal paradigm was fleshing out the logic of commercial peace, scholars like Kenneth Waltz and Joanne Gowa were arguing that interdependence could actually increase the likelihood of conflict. For one thing, high levels of trade can also increase frictions, triggering an interstate dispute. For another, as Waltz noted, increased interdependence implies a more specialized division of labor. As specialization increases dependency on others, according to Waltz (p. 106), states react defensively: “like other organizations, states seek to control what they depend on or to lessen the extent of their dependency. This simple thought explains quite a bit of the behavior of states: their imperial thrusts to widen the scope of their control and their autarchic strivings toward self-sufficiency.” China’s rapacious desire to lock down access to raw materials and critical minerals could be viewed as a modern-day manifestation of Waltz’s prediction.

China’s overall rise also posed a challenge to the liberal theory of interdependence. Critics highlight U.S. President Bill Clinton’s March 2000 speech advocating for China’s entry into the WTO. In that speech, he promised, “the more China liberalizes its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people—their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise. And when individuals have the power not just to dream but to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.” A generation later, that promise has clearly been unfulfilled (though Clinton’s support for China’s WTO accession had other, arguably more important, objectives beyond political liberalization). China’s turn toward even more illiberal forms of autocracy in Hong Kong and Xinjiang are the most obvious manifestation of this broken promise.

Farrell and Newman’s development of the weaponized interdependence concept added a new level of concern. Scholars had long been aware that some states might be vulnerable to asymmetric dependence on larger economies. What Farrell and Newman proposed was that the globalized economy was dependent on networks and standards that were difficult for any actor to exit. Furthermore, these networks were not decentralized. Whether one looked at finance, the internet, or energy, central nodes emerged. As Farrell and Newman explained, “In contradistinction to liberal claims, [network structures] do not produce a flat or fragmented world of diffuse power relations and ready cooperation, nor do they tend to become less asymmetric over time.… Contrary to Keohane and Nye’s predictions, key global economic networks have converged toward ‘hub and spoke’ systems, with important consequences for power relations.”

Two events helped bolster the fear that weaponized interdependence had generated in the corridors of power. First, the coronavirus pandemic convinced many observers that excessive dependence on international sourcing left their countries vulnerable to supply shocks. As Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright noted, China bought up all the personal protective equipment (PPE) in the first quarter of 2020, thereby leaving many countries high and dry when COVID-19 went global. Canada’s domestic procurement of PPE increased 250-fold after March 2020. The pandemic generated an entire discourse about how resiliency needed to be prioritized over efficiency. According to European Commission Vice President Věra Jourová, COVID-19, “revealed our morbid dependency on China and India as regards pharmaceuticals.” Japan launched a $2.2 billion fund to assist companies shifting production facilities out of China.

Second, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has highlighted all the ways that Europe has been dependent on Russian energy. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg stated, “The war in Ukraine has … demonstrated our dangerous dependency on Russian gas. This should lead us to assess our dependencies on other authoritarian states, not least China.” The parallels between Russia’s irridentist desire for Ukraine and China’s ardent desire to absorb Taiwan are difficult to ignore. The return to great power competition has fed a belief that economic security must be prioritized over the efficiency gains from globalization.

How Economic Interdependence Has Actually Affected World Politics

While contemporary fears about excessive interdependence are real, that does not mean that these fears have been realized. Indeed, a quick perusal of the alleged downsides of interdependence reveal that much of what has been feared has not come to fruition.

For example, consider the allegations about how China gamed the liberal international order to serve its own revisionist ends. It is undeniably true that as China has grown economically stronger, it has also grown more repressive and more revisionist. Neither of these facts, however, falsify the liberal theory of international politics. The liberal argument posits that interdependence constrains rising powers from pursuing more bellicose policies than they otherwise would have. It says next to nothing about interdependence triggering democratization. It is possible that China can repress domestically while still acting in a constrained manner on the global stage. Most of China’s alleged revisionist actions have been exaggerated. For example, neither the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) bank nor the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have challenged the Bretton Woods Institutions. Claims that the Belt and Road Initiative is an example of debt-trap diplomacy have also been wildly exaggerated; indeed, if anything, China’s recent lending practices suggest that it will not weaponize debts from the Global South. While China has built new institutions outside the purview of the United States, none of them contradict the principles of the liberal international order.

As for China’s foreign policy more generally, the evidence that complex interdependence has failed is scant. By one metric, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) surpassed the United States in recent years. As Graham Allison has noted, over the past few centuries, such a great power transition caused a war 75 percent of the time. While Sino-American relations have grown more fraught in recent years, war has not broken out—and that dog not barking might be the most important data point in favor of complex interdependence. Stacie Goddard argues that China’s rise within the liberal international order has enabled it to engage in some revisionist actions, but its interdependence with the rest of the world has also constrained that revisionism. The evidence that China seeks to upend this order wholesale remains scant. Iain Johnston concluded, “It is problematic to claim that China is less economically open to trade today than in 1997, or less supportive of the arms control regimes it has joined than in 1997, or less committed to global counterterrorism today than in 1997, or less committed to dealing with greenhouse gases today than in 1997.” My own research suggests that if China is intending to upend the global economic order, it is doing so in a radically suboptimal manner.

China’s autonomy has grown as its wealth has increased—but like every other actor in the international system, it remains constrained by its reliance on the global economy. Perhaps the best evidence for this is its constrained response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia is China’s most important geopolitical partner on the global stage. Just a few weeks before the invasion, Russia and China publicly proclaimed a friendship without limits. Despite this bonhomie and confluence of national interests, China’s support of Russia since the start of the war has been decidedly meager. China has refrained from shipping weapons or other forms of materiel support to a Russia that badly needs it. That is due in no small part to the fact that China values its economic relationship with the West far more than it does its relationship with Russia.

Similarly, fears that the pandemic created vulnerabilities for economies dependent on global supply chains proved to be wildly misplaced. Ironically, most of the pandemic-induced stresses had to do with the private sector underestimating the robustness of government responses. As COVID-19 went global, firms responded by drastically scaling back production, anticipating a massive consumer slowdown. Instead, fiscal and monetary stimulus caused shifts in the composition of demand, mostly from services to manufactured goods. This caught many firms flatfooted, leaving them to scramble for newly scarce inputs. Furthermore, there was zero evidence that goods with more complex global supply chains suffered more severe disruptions than goods with regional supply chains. Indeed, if anything, the evidence suggests the opposite: precisely because supply chains were globalized, they were more resilient to regional shocks. This was because those firms who relied on global supply chains were more conscious about the possibility of disruption, thereby taking action to forestall it. By contrast, one of the most autarkic of U.S. products—baby formula—suffered one of the period’s deepest and longest shortages, which the federal government tried to alleviate by embracing imports.

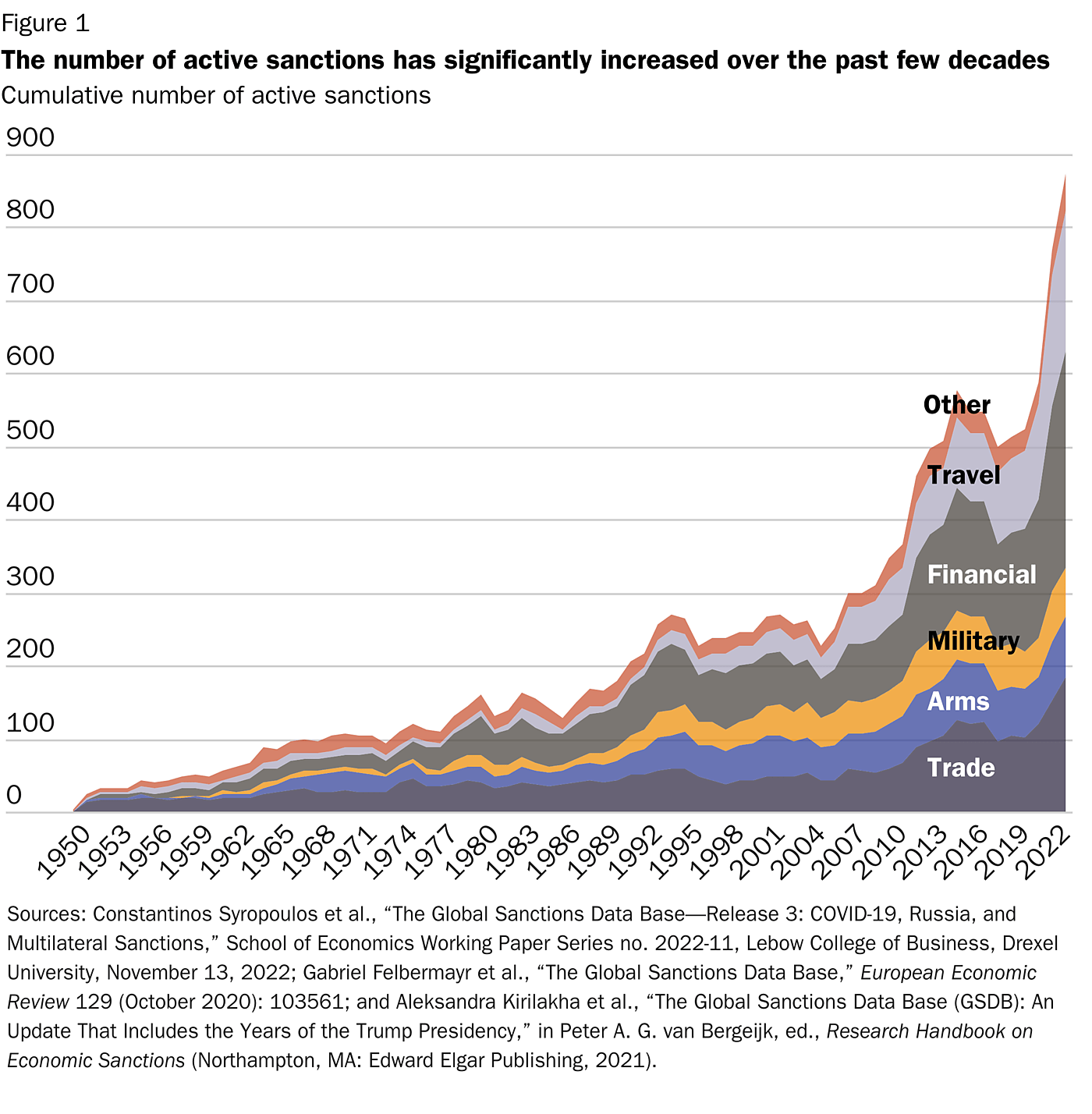

As for fears about weaponized interdependence, the rate of sanctioning activity has increased considerably over the past few decades, as Figure 1 demonstrates.

The evidence to date suggests that while great powers have tried to exploit their network centrality to impose economic coercion, few of these events have been successful. The most prominent success was the joint U.S.-EU sanctions against Iran that forced that country to sign the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Interestingly, however, when the Trump administration exited the JCPOA and reimposed sanctions, the results were lackluster even though Iran suffered severe economic costs. As Esfandyar Batmanghelidj noted, “That the subsequent economic crisis in Iran was as severe as when multilateral sanctions were imposed in 2012 speaks to the unique power of U.S. economic coercion.” Soon after their reimposition, Iran’s oil exports fell by more than 50 percent, its GDP contracted by 6 percent, and the value of its currency fell by more than 60 percent. Basic goods nearly doubled in price in 2019. More than 80 percent of Iran’s oil exports were cut due to the reimposed sanctions. The International Monetary Fund reported that Iran’s gross official reserves had plummeted from $122.5 billion in 2018 to only $4 billion in 2020.

While the costs to Iran were severe, the sanctions did not achieve stated U.S. intentions. The most obvious proof of failure was Iran’s decision to restart its nuclear program. Tehran had complied with the JCPOA since its adoption on October 18, 2015. In May 2019, however, Iran breached the accords by exceeding limits on heavy water and enriched uranium stockpiles. Two months later, Iran announced that it would exceed the 3.67 percent uranium-235 enrichment limit and go up to 4.5 percent. Two months after that, Iran stated that limitations on research and development of advanced centrifuges would no longer be respected. By January 2020, Iran announced that it would no longer be bound by any operational limitations of the JCPOA. Estimates for how long it would take for Iran to build a nuclear bomb fell from a year under the 2015 deal to a few weeks in 2021. Simply put, Iran was willing to pay the price of sanctions to pursue its own national security policies.

Iran is a middle-range power. Attempts to weaponize interdependence against great powers have been even less successful. The sanctions imposed against Russia after the 2014 annexation of Crimea clearly failed to deter Russia from further aggression. The economic coercion implemented after the 2022 invasion was unprecedented, but the aggregate impact on Russia’s economy was considerably less than analysts anticipated. Russia’s countersanctions also proved to be less than meets the eye, as Europe dealt with Russia’s energy cutoff far better than expected. It is possible that over time, the West’s sanctions against Russia will degrade Russia’s military capacities. Still, given all the fears about the power of weaponized interdependence, it is noteworthy that sanctions failed at both deterring and coercing Russia from invading Ukraine.

The unprecedented country-specific export controls put in place against China may have the desired effect of extending the United States’ technological lead over its closest competitor. The more specific controls placed on access to Huawei seriously dented that firm’s efforts in the smartphone market. The broader export controls put in place in October 2022, however, are less likely to succeed. In 1999, concerned about leaks of satellite technology to China, the United States blocked American firms from providing U.S. satellites to be launched on Chinese rockets. At the time, the U.S. dominated the satellite export market, controlling 73 percent. In response, China found alternative satellite suppliers—France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and even Ukraine. Within six years, the export controls proved to be a complete failure, as the U.S. share plummeted to 25 percent. On semiconductor chips, Washington has managed to attract more multilateral support, but China is also in a stronger position to compete.

Weaponized interdependence has whetted the appetite for economic coercion around the globe. The combined effect of recent measures and countermeasures, however, has been to create a global economy in which economic sanctions are frequently imposed but yield minimal concessions. Long-lasting sanctions will have knock-on effects on patterns of global investment. The result is a global political economy that more closely resembles older, less stable eras. Consider the interwar era, when sanctions helped destabilize the international system. The League of Nations sanctions against Italy in response to its invasion of Ethiopia encouraged the Axis powers to pursue more autarkic policies; the U.S. oil embargo of Japan led that country to bomb Pearl Harbor. Sanctions in this century will likely accelerate the trend toward geoeconomic fragmentation—economic and technological decoupling by attrition.

Weaponized Interdependence and the Power of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Fears of excessive dependence are not unique to the 21st century. For much of the 20th century, there was concern that the great powers would be vulnerable to the cutoff of hydrocarbons. Fears of oil wars, however, turned out to be misplaced. Nonetheless, the concern about the prospect of resource wars, or being vulnerable to weaponized interdependence, highlights a second-order concern: that the fears about malevolent interdependence prove to be self-fulfilling prophecies. Or, to put it another way: Angell was absolutely correct when he argued in The Great Illusion that war was a horribly inefficient way for countries to enrich themselves as compared to trade. His error was in presuming that this fact would be so obvious to everyone that war would not happen. Writing just a few years before the start of World War I, Angell turned out to be badly mistaken.

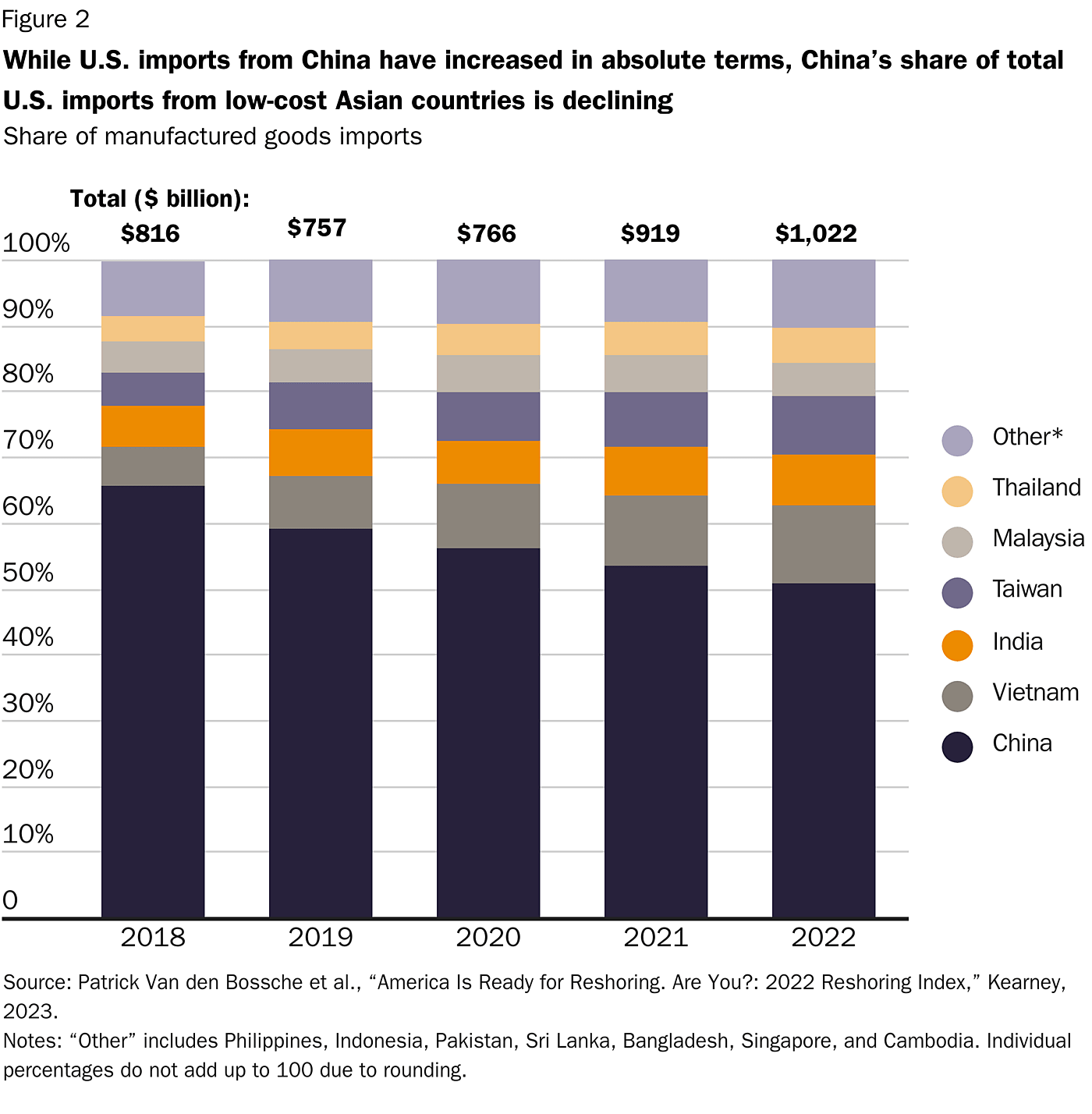

Unfortunately, Angell’s successors have made similar arguments about war being rendered obsolete. If the wars of this century yield any lesson, it is that policymaker misconceptions can often turn into self-fulfilling prophecies. If the United States and China, for example, become convinced that they are targets to malevolent interdependence, they will take actions to decouple their economies from each other. In doing so, however, they would weaken the positive constraints that complex interdependence has placed on their foreign policies. While China and the United States continue to be each other’s largest trading partner, that interdependence is lessening. As Figure 3 shows, in 2013, China was responsible for nearly 70 percent of U.S. imports from Asia. In 2022, that figure had declined to 50 percent. The perceptions fostered by trade wars, the pandemic, and escalating geopolitical risk will cause that figure to decline even further. Just as the United States is talking about “de-risking” the West from China, Chinese officials stress the need for a “dual circulation” economy less dependent on export-led growth.

International relations scholarship has demonstrated the power of myths and misperceptions to trigger armed conflict. While this essay has demonstrated that fears about excessive dependence have been exaggerated, a bipartisan elite consensus has calcified this fear into a stylized fact that is barely grounded in reality. Policymakers need to be more conscious about the tradeoffs between too much economic interdependence and too little economic interdependence before taking actions that increase the likelihood of a great power war.

Conclusion

The neoliberal consensus about globalization is—rightly or wrongly—dead; the international relations consensus about the virtues of interdependence died along with it. Countries are erecting measures and countermeasures designed to reduce their dependency on the global economy. Some of this has been driven by the externalities allegedly created by globalization. Some of this has been driven by the desire for post-neoliberal ideas that encourage industrial policies and discourage untrammeled free trade. And some of it has been driven by the belief that the liberal theory of international politics has been falsified.

This essay has demonstrated that most of the fears about interdependence have been misplaced. Globalization is not responsible for Chinese bellicosity, and it is not responsible for the pandemic-fueled shortages. While weaponized interdependence is a real phenomenon, national governments have wildly exaggerated their capacity to exploit it to advance their own foreign policy ends. The result has been a lot of sanctioning activity and very few concessions to show for it. Going forward, the danger is that in attempting to ward off weaponized interdependence, the United States, China, and other great powers will pursue policies that make it easier to conceive of great power conflict. If post-neoliberal ideas take root even if they lack empirical validity, the result will be a world far more primed for war.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.