Who should pay for the damages caused by natural disaster? The American ethos has long called on personal responsibility and private charity, rather than broad public aid, to secure people’s welfare. Although public emergency services play a vital role during and immediately after a catastrophe, this ethos looks to private insurance and disaster-oriented organizations, such as the Red Cross, to be the main modes of recovery from a flood or storm, as well as prior care in siting and constructing buildings to blunt the effects of wind and rain.

Despite this, the federal government has often come to the financial assistance of Americans harmed by mass calamity. But public aid crowds out private relief and dampens incentives for private insurance and damage prevention.

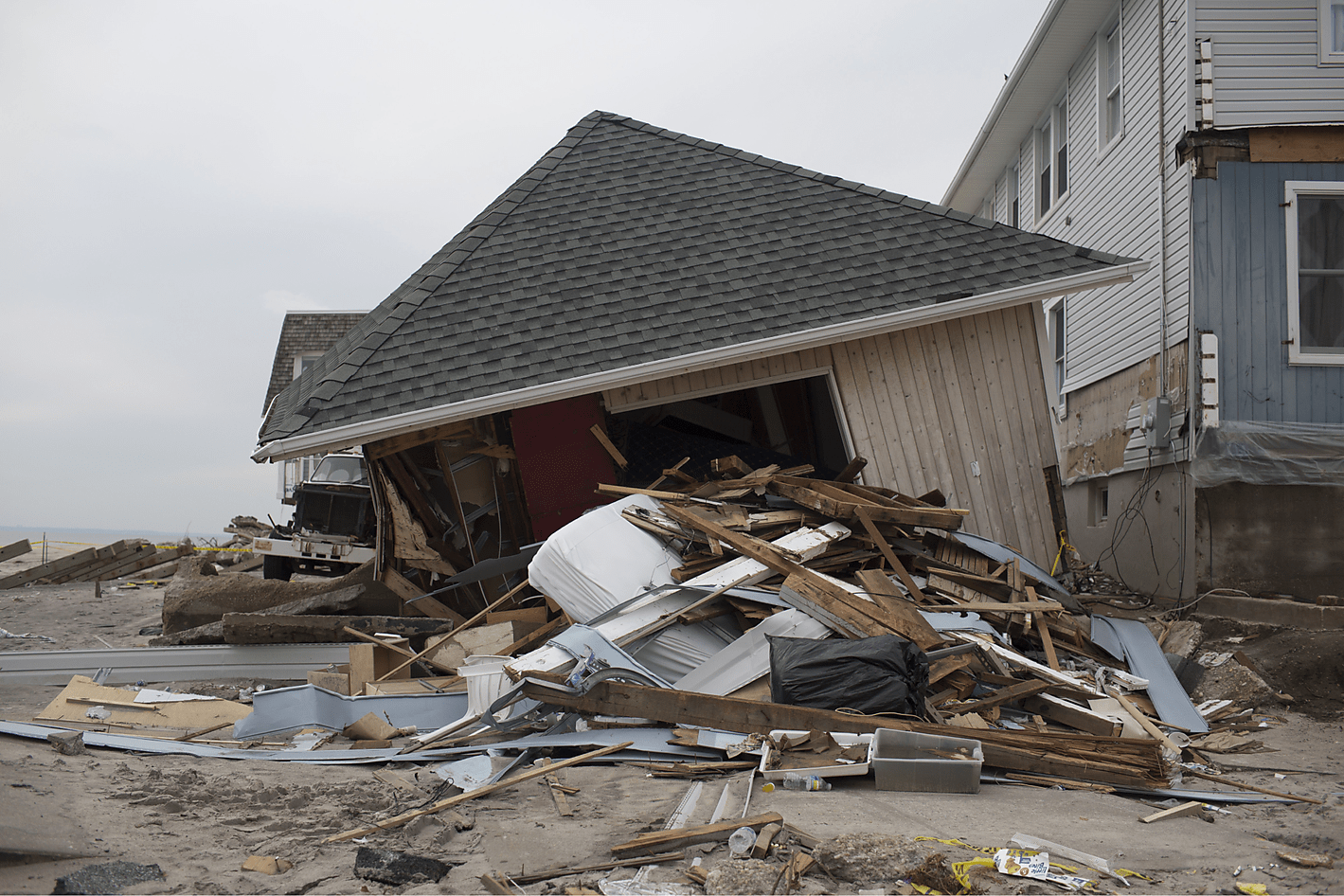

Policymakers thus face the Samaritan’s dilemma: either render aid after a catastrophe or else withhold aid to encourage people in calamity-prone areas to purchase disaster insurance, take preemptive measures to reduce losses, and build robust private charity systems. To achieve the latter, elected policymakers must effectively “precommit” to not rendering financial aid, warding against the temptation to backtrack when the public sees heart-rending images of disaster victims.

Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program in 1968 to escape the Samaritan’s dilemma in a politically palatable way. Despite its flaws, the program is preferable to a return to the regular appropriating of ad hoc aid, which was the case before the program was implemented. The most important step Congress can take is to return to the original intention that it charge unsubsidized, actuarially fair rates for structures covered under the program.

Introduction

The federal government has often come to the financial assistance of Americans harmed by mass calamity. Even in the Founders’ era, in 1803, Congress enacted a form of disaster relief by suspending the bond payments owed by Portsmouth, New Hampshire, merchants for several years after a fire struck the seaport. In keeping with the young nation’s values, President Thomas Jefferson also anonymously donated $100—the equivalent of $2,400 today—for humanitarian aid to the city’s residents.1

The impulse for government-provided disaster assistance is understandable. But public aid crowds out private relief and dampens incentives for private insurance and damage prevention. At the international level, economists Paul Raschky and Manijeh Schwindt of Australia’s Monash University tested for this effect using data from 5,089 natural disasters in 81 developing countries over the period 1979–2012. They found that “past foreign aid flows crowd out the recipients’ incentives to provide protective measures that decrease the likelihood and the societal impact of a disaster.”2

Policymakers thus face what is known as the Samaritan’s dilemma3: the choice to either render aid after catastrophes or else, seemingly heartlessly, withhold aid, which would have the benefits of encouraging people in calamity-prone areas to purchase disaster insurance, take preemptive private and local public measures to reduce losses, and build robust private charity systems for when catastrophe strikes. To achieve the latter, elected policymakers must effectively “precommit” to not rendering financial aid, warding against the temptation to be “time inconsistent” and backtrack when the public sees heart-rending images of disaster victims.

The National Flood Insurance Program

Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) in 1968 to escape the Samaritan’s dilemma in a politically palatable way. In prior decades, lawmakers had routinely handed out ad hoc aid to flood and storm victims. The NFIP was intended to reduce such aid and protect federal taxpayers while providing prospective flood victims with a way to financially protect against loss.

The NFIP is a government program, but lawmakers wanted it to charge most insureds roughly actuarially fair premiums. Although buildings constructed prior to the passage of the legislation would qualify for discounted rates (and thus receive public subsidy), owners of subsequently built structures who purchased coverage would, in effect, prepay the cost of restoring their properties following catastrophe. The program also requires that, for buildings in high-risk areas to qualify for coverage, those areas must be zoned to limit construction, and local building codes must include provisions to make new structures better able to withstand floodwaters, such as by requiring their main levels to be elevated above typical floodwaters.

Except for the grandfathered preexisting structures, lawmakers intended for the NFIP to be largely free of subsidies, thus protecting taxpayers. The 1966 task force report that gave rise to the NFIP originally estimated that federal subsidization of the cost of flood premiums for existing high-risk properties would be required for a limited period of time only—approximately 25 years—a prediction that would prove to be wildly optimistic.4 The percentage of subsidized policies has decreased over time, but after a half century of the program they have not disappeared. And in the past decade, Congress has partly retreated from the commitment to end the subsidies.

So, what should be done about flood disaster policy going forward? Although private flood insurance has entered the market in the last few years, there are serious questions about whether it will persist over the long term. And elected policymakers are highly unlikely to ignore the plight of large groups of people whose homes are struck by floodwaters. Yet, a return to the ad hoc aid of the mid-20th century is undesirable. So, although flawed, the NFIP likely is the best policy response that is politically attainable. That said, the program can be improved, and the most important step Congress can take is to return to the original intention that the NFIP charge unsubsidized, actuarially fair rates for covered structures.

Related Read

Reforming the National Flood Insurance Program: Toward Private Flood Insurance

A fully private flood insurance market coupled with a targeted, means-tested subsidy would be much less regressive than the status quo.

Pre–National Flood Insurance Program Federal Disaster Policy

Between 1803 and 1947, Congress enacted at least 128 specific legislative acts offering ad hoc relief after disasters.5 But some disasters were followed by no federal response. For example, in 1887 President Grover Cleveland vetoed drought relief for Texas.

As shown in Figure 1, until the 1960s, federal disaster policy mostly focused on engineering solutions rather than relief. For instance, in 1879 Congress created the Mississippi River Commission to coordinate private levee projects to avoid the problem of one area solving its flooding problems by building levees to divert the waters to other areas. But Midwest businessmen lobbied for a sustained federal financial commitment to manage Mississippi floods. Congress authorized a round of federal flood control spending as part of the Mississippi River Commission’s work in 1917 and again six years later, but local funding was still required to cover one-third of the costs.6

The Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927 resulted in permanent federal responsibility for controlling flooding along the river under the Flood Control Act of 1928.7 That responsibility expanded to the entire country in the Flood Control Act of 1936.8 This aid was overwhelmingly directed toward building flood control projects.9

This began to change with the Disaster Relief Act of 1950 (now known as the Stafford Act), which assumed federal responsibility for the repair and restoration of local public infrastructure after disasters.10 Overall, federal responsibility for disaster recovery spending began to grow. From 1955 through the early 1970s, federal disaster relief expenditures increased from 6.2 percent of total damages after Hurricane Diane in 1955 to 48.3 percent after Tropical Storm Agnes in 1972.11

Where Was Private Flood Insurance?

In many calamities, private insurance provides relief following a loss: auto insurance covers those harmed in a car crash and homeowner’s insurance covers losses in a house fire or burglary, for instance.

And at various times in American history, private insurers have offered flood coverage. But the magnitude of losses from major floods frequently pushed insurers into bankruptcy, and until very recently, no reputable insurer had offered flood insurance since the 1927 Great Mississippi Flood. As Wharton School economist Howard Kunreuther and others explained in a 2019 paper:

In 1897, an insurance company offered flood insurance to property along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers motivated by the extensive flooding of these two rivers in 1895 and 1896. Two floods in 1899 not only caused the insurer to become insolvent since losses were greater than the insurer’s premiums and net worth, but the second flood washed the office away. No insurer offered flood coverage again until the 1920s, when thirty fire insurance companies offered coverage and were praised by insurance magazines for placing flood insurance on a sound basis. Yet, following the great Mississippi flood of 1927 and flooding the following year, one insurance magazine wrote: “Losses piled up to a staggering total.… By the end of 1928, every responsible company had discontinued coverage.”12

Can private flood insurance be economically viable? Much scholarly discussion on this question has been vague rather than definitive: “The experience of private capital with flood insurance has been decidedly unhappy,” wrote two academics in a 1955 book.13 “From the late 1920s until today, flood insurance has not been considered profitable,” noted the Congressional Research Service in a 2005 report.14 Kunreuther and others quote a commenter in a May 1952 industry publication offering this blunt assessment:

Because of the virtual certainty of the loss, its catastrophic nature, and the impossibility of making this line of insurance self-supporting due to the refusal of the public to purchase insurance at rates which would have to be charged to pay annual losses, companies could not prudently engage in this field of underwriting.15

Below, this analysis will discuss the difficulties for private flood insurance viability.

Government Insurance

With no private flood insurance available to property owners, in the mid-20th century Congress took on an increasing role in providing disaster relief. But lawmakers realized that in doing so they were placing a growing burden on taxpayers.

When Congress appropriated relief funds for storms that devastated the South in 1963 and 1964, and for flood losses on the upper Mississippi River as well as Hurricane Betsy in 1965, the legislation included a provision directing the Department of Housing and Urban Development to study whether a federal flood insurance program would be a desirable alternative to ad hoc disaster relief.16 The resulting 1966 report recommended such a program, adding that any federal premium subsidies should be limited to existing structures in high-risk areas, while new construction should be charged actuarially fair rates.17

Congress enacted the National Flood Insurance Act in 1968, incorporating most of the study’s recommendations. Although structures erected prior to the full implementation of the legislation qualify for subsidized premiums, all other covered structures ideally pay full actuarial rates, although only for floods estimated to occur with at least 1 percent annual frequency.18 More rare floods, so-called catastrophic events, with an annual probability of less than 1 percent, are implicitly insured by the Treasury. Flood-prone areas that are eligible for NFIP coverage are designated on Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) that were drawn under the legislation and are periodically updated. According to a 2015 National Research Council report, “The expectation was that, over time, the properties receiving pre-FIRM subsidized premiums would eventually be lost to floods and storms and pre-FIRM subsidized premiums would disappear through attrition.”19

But details of the 1968 legislation meant that even “unsubsidized” NFIP premiums do not fully cover the costs of the catastrophes striking those properties. For instance, the National Research Council report explains, “The legislation stipulated that the US Treasury would be prepared to serve as the reinsurer and would pay claims attributed to catastrophic-loss events.”20 A reinsurer is, in essence, an insurer for the insurer, so federal taxpayers ultimately backstop the NFIP program in the event of severe losses. As a result, even post-FIRM buildings receive some degree of taxpayer subsidy.

Land-Use Controls

Actuarially fair rates were only one way the NFIP was supposed to reduce taxpayer exposure to losses. The statute also included the aforementioned zoning requirements to limit construction in flood-prone areas and building code requirements intended to make structures built in those areas less vulnerable to flood damage.

Under the 1968 law, federal flood insurance is available only in communities that agree to land-use controls that limit construction in a high-risk area—a so-called “100-year floodplain,” known officially as a Special Flood Hazard Area.21 Structures in communities that have not adopted those zoning controls cannot receive mortgages sponsored by, or sold to, any federal agency, including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration, and the Veterans Administration.22 According to University of Florida law professor Christine A. Klein:

Such regulation would constrict the development of land which is exposed to flood damage and minimize damage caused by flood losses. Second, regulation would guide the development of proposed future construction, where practicable, away from locations which are threatened by flood hazards.23

Although Congress intended for construction to retreat from the floodplains, NFIP rules have always allowed new construction in the zones provided that the structure’s first floor is elevated above the high-water level predicted to occur with 1 percent annual probability, the so-called Base Flood Elevation (BFE). The 1968 statute also requires elevation for pre-FIRM properties that subsequently are “substantially damaged or substantially improved, which triggers a requirement to rebuild to current construction and building code standards.”24 From the beginning of the program, federal regulation has defined “substantially damaged and substantially improved” as repairs or alterations that equal or exceed 50 percent of the market value of the structure before damage or renovation occurred.25 So, despite the initial intent of the 1968 legislation to abandon structures and development in floodplains, the rules quickly allowed rebuilding—with elevation and engineering improvements.

Making the National Flood Insurance Program Subsidies Disappear?

The inclusion of these land-use and building code provisions in addition to true actuarial pricing has been justified historically as lawmakers attempting to curtail moral hazard.26 At least that was the thinking in 1968.27 But this justification does not make sense for two reasons.

First, if homeowners pay higher premiums that adequately cover the risk presented by their vulnerable, nonfloodproofed homes, there is no moral hazard, strictly speaking. The higher premiums encourage structure owners to elevate their buildings if the cost of doing so, plus the present value of the lower premiums associated with elevated structures, is less than the present value of the premiums for structures that are not elevated. Also, regardless of whether a property owner elevates a structure, if the premiums for pre-FIRM structures were not subsidized, the government and taxpayers should be indifferent to paying claims for repetitive losses.28

Second, moral hazard is an increase in the incidence of actual damages (by those who are insured) relative to the estimated incidence that is used by insurance companies to calculate rates because of unobserved behavior on the part of insureds that increases the incidence. But it is easy to observe whether a structure’s first floor and important utilities (heating, air conditioning, hot water, and telecommunication and electrical interfaces) have been elevated above the BFE when assigning it to an actuarially fair rate class. Thus, although moral hazard is offered as a rationale for employing land-use and building-code controls in addition to actuarial prices, the term apparently is being used in a casual, rather than rigorous, fashion.

The more likely reason for these requirements is to further protect lawmakers from the Samaritan’s dilemma. Members of Congress and the executive branch appreciate the political forces associated with disaster relief. Given constituents’ desire for government-provided aid, the land-use and building-code requirements can be seen as a commitment device to eliminate, over time, the subsidies for the grandfathered pre-FIRM structures. Eventually, all pre-FIRM structures would be abandoned or rebuilt in such a way that they would not be subject to flooding losses.

And overall, this bit of political engineering appears to have been successful. The percentage of NFIP-covered structures receiving pre-FIRM subsidies fell dramatically over the first five decades of the program. Some 75 percent of covered properties received this subsidy in 1978, but only about 28 percent in 200429 and 13 percent in September 2018.30

It should be noted that the elevation requirement does not appear to be rigorously enforced. A 2020 New York Times investigation revealed there are 112,480 NFIP-covered structures nationwide with first floors below BFE where the property owners are paying premiums that are not reflective of that risk. The owners filed 29,639 flood insurance claims between 2009 and 2018, resulting in payouts of more than $1 billion—an average of $34,940 per claim.31

The NFIP also includes cross subsidies between different groups of insureds. One instance reflects the type of flooding a property is subject to. Within the 100-year floodplain, land is divided into two categories: one for coastal areas that face tidal flooding (“V” zones) and thus are especially high-risk and should pay higher actuarially fair rates, and the other for ordinary, nontidal flooding (“A” zones).32 A property that is initially mapped in zone A and is built to the proper building code and standards, and then later is remapped to higher-risk zone V, is entitled to continue paying zone A premiums if the property has maintained continuous NFIP coverage. That subsidy is financed by other NFIP participants, who pay premiums above actuarially fair levels.

Another instance involves the remapping of BFE levels. If an updated FIRM indicates that an elevated property now faces a higher risk of flooding—say, a property that was initially mapped as being four feet above BFE but is reappraised as being just one foot above BFE—the property owner can continue to pay the previous, lower-risk premium. As of September 2018, about 9 percent of NFIP policies received cross subsidies from one of those two forms of grandfathering.33

Related Read

The Unintended Effects of Government-Subsidized Weather Insurance

These programs are a boon to the wealthy and encourage development in disaster-prone areas.

Step Forward, Step Back

In 2012, lawmakers took a big step toward curtailing NFIP subsidies by enacting the Biggert-Waters Flood Reform Act. Under the legislation, premiums for nonprimary residences, severe repetitive loss properties, and business properties (about 5 percent of policies) were to increase 25 percent per year until they reflected the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) best estimate of their flood risk.34 Pre-FIRM single-family homes had to have elevation certificates indicating BFE levels to ensure proper pricing because rates vary with the elevation of the structure above BFE. Grandfathering of structures from zone and elevation reclassification was to be phased out through premium increases of 20 percent per year until the actuarially fair prices were reached.35 Finally, the sale of any grandfathered properties would subject the new owner to actuarially fair rates for coverage.

But after Hurricane Sandy hit politically important New Jersey and New York later in 2012, and FEMA subsequently released new flood maps indicating increased risk, thousands of homeowners were faced with large premium increases.36 Congress retreated from the Biggert-Waters reforms when it enacted the 2014 Homeowners Flood Insurance Affordability Act.37 The NFIP’s original grandfathering provisions were reinstated. The assessing of actuarial levels upon sale of a property was repealed.38 And most properties newly mapped into a 100-year floodplain after April 1, 2015, received initially subsidized premiums for one year, although they then increase 15 percent per year until they are actuarially fair. As of September 2018, about 4 percent of NFIP policies received this last form of subsidy.39

How much do the NFIP subsidies reduce premiums? In 2011, FEMA estimated that policyholders with discounted premiums were paying roughly 40–45 percent of the full-risk price.40 Later in the decade, FEMA estimated “that the receipts available to pay claims represent 60 percent of expected claims on the discounted policies.”41

The Problems Faced by Private Flood Insurance

Private insurance is a contract between risk-averse individuals and insurers, in which the insurer assesses a risk-based premium of its insureds and then covers the cost of their losses in a catastrophe.

Insurers calculate their premiums using population-level data on the incidence of damages. Roughly speaking, if individuals with the same probability of damages randomly purchase insurance, insurers can charge each of them the average damage cost and, in return, protect them from high losses.42 Insured individuals whose actual damages are below the average will, in essence, pay for the damages incurred by those whose damages are above the average.

Insurance works only if potential insureds have no knowledge about their likely future damages relative to the average.43 In the absence of such knowledge, insureds would be willing to pay for coverage (if the premium is the average amount of loss and they are risk averse) because they prefer the certainty of that payment every year over the risk of being burdened with a much higher loss from a rare disaster.

Unfortunately, floods have characteristics that require insurance companies to charge more than the average damages, which limits consumer demand for private, unsubsidized insurance. As explained in a 2012 article by the Wharton School’s Carolyn Kousky and Resources for the Future’s Roger Cooke, three statistical characteristics subject flood insurers to the risk of insolvency even if they get their actuarial work right and if they assemble a large pool of equally risky insureds: dependence among events, fat-tailed frequency distributions, and tail dependence.44

Dependence

Flood risk tends to be spatially correlated, meaning that when a disaster hits a region, many structures are affected simultaneously. Insurers can dampen this risk by increasing the spatial distance between policies. Ideally, insurers could space out their policies far enough that the correlation is zero. In that case, the actuarially fair price for coverage would be the sample average loss of a spatially diverse set of policies because the probability of damages from any policy would be random (independent) within the population of insurance policies.

But such diversification is hard to achieve because flooding risk is largely confined to specific geographic areas. If there is even a small positive correlation among policies, it significantly increases the risk of loss faced by the insurer.45 Claims tend to occur in “clumps” drawn from the population of policies. To ward against insurer insolvency from clumped claims, premiums would have to be much greater than the average loss, depending on how large the correlation is among claims. Kousky and Cooke base their analysis using the small but positive correlation of .04 among flood claims at the level of U.S. counties (correlations range from 0, meaning no relationship, to 1, meaning a perfect relationship), but a world portfolio would presumably have less correlation. Kousky and Cooke seem to admit this: “It is important to keep in mind that this finding was for highly concentrated insurers in Florida and thus is not broadly applicable, but is an example of insurance for a catastrophic risk.”46

Kousky and Cooke use annual flood claim data from flood-prone Broward County, Florida, to conduct a simulation to demonstrate this risk and its effect on flood insurance pricing (see Figure 2).47 If an insurer had 100 policies with Broward County characteristics and claims were independent, it would have to charge 1.51 times the average claim to stay solvent with 99 percent probability. Demonstrating the benefits of more predictable results from holding a larger portfolio of policies, if the insurer had 200 policies, it would only have to charge 1.34 times the average claim.

However, at the county level, there is dependence in flood claims in the United States. Claims exhibit a correlation of 0.04, which is a small positive correlation.48 Introducing that level of dependence into Kousky and Cooke’s simulation requires premiums that cost 2.17 times the average loss for the insurer to remain solvent with 99 percent probability if it holds 100 policies, and 2.10 times the average loss if it holds 200 policies. In a separate simulation using 10,000 policies, Kousky and Cooke demonstrate that the required premiums increase relative to the average loss, even for correlations of less than .003.

Such high premiums do not necessarily make flood insurance an impossibility, but risk-averse property owners would have to be willing to pay these expensive premiums, which may range from $20,000 to $30,000 for $250,000 worth of insurance coverage.

Fat Tails

If events are “fat-tailed,” extreme results are more likely. According to Kousky and Cooke, “Many natural catastrophes, from earthquakes to wildfires, have been shown to be fat-tailed.”49

They incorporated fat tails into their simulation—specifically, “a fat-tailed Pareto distribution with mean 1 and a tail index of 2, indicative of infinite variance—a very fat tail.”50 The required premiums to ensure 99 percent insurer solvency had to be 1.77 times the average losses for 100 county policies and 1.49 for 200 policies if claims were independent. The authors then also assumed dependence, and using the 0.04 correlation in U.S. county-level data, they found that premiums needed to be 2.45 times (for 100 policies) and 2.31 times (for 200 polices) the average losses for 99 percent probability of insurer solvency.

Kousky and Cooke are not that transparent about how generalizable their results are to all fat-tailed distributions. While they state that they study the effects of fat-tailed damage claim distributions, they actually only study the effects of one particular distribution, do not tell the reader how representative it is, and hint that it is not generalizable.

Tail Dependence

Tail dependence means that “clumps” of claims are more likely to occur simultaneously (rather than randomly) on the right, high-cost side of the frequency distribution of claims. According to Kousky and Cooke:

Tail dependence refers to the probability that one variable exceeds a certain percentile, given that another has also exceeded that percentile. More simply, it means bad things are more likely to happen together. This has been observed for lines of insurance covering over 700 storm events in France. Different types of damages can also be tail dependent, such as wind and water damage, or earthquake and fire damage.51

Kousky and Cooke incorporated tail dependence in their simulation. They found that premiums would need to be 3.7 times higher than the average claim, regardless of whether the insurer holds 100 or 200 policies in the county, to ensure insurer solvency for a lognormal distribution of claims like those in Broward County, Florida.52

The real problems came when they incorporated all three of these characteristics (dependence, a fat-tailed Pareto distribution with mean 1 and a tail index of 2, and tail dependence) simultaneously into their simulation. They found that to ensure 99 percent probability of insurer solvency, premiums had to be 4.43 times average losses for 100 policies and 8.69 times average losses for 200 policies.53 That is, the larger an insurer’s portfolio of covered properties, the higher it would have to set its individual premiums to reduce the probability of insolvency.

The implication of this analysis is not that private insurance is impossible, but that the premiums required for 99 percent probability of insurer solvency are far above the amount of the average claim, even if the insurer has correctly ascertained the risk posed by its insureds. If claims are dependent rather than independent, then the reduction in premiums arising from portfolio diversification is reduced. And fat-tail dependence, if it exists in the form Kousky and Cooke assume, places severe constraints on private and public insurance. The more policies that are written, the greater the required premiums must be, relative to the average claim, if the insurer is to have enough assets to stay solvent with 99 percent probability.

How Can Private Flood Insurance Exist?

Even though the previous section explained why flood insurance, in theory, would have to be priced higher than the average claim (ignoring marketing and transaction expenses as well as a normal return on equity),54 some private flood insurance does exist, primarily for commercial and secondary coverage above NFIP limits.55 The 2012 Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act directed FEMA to allow private insurance coverage that was equivalent to NFIP coverage to qualify as complying with the requirement that homes have flood insurance if they are located in flood zones and have federally sponsored mortgages.56 The agency took seven years, until July 2019, to write the regulations implementing the statute. Under pressure from Congress, FEMA also removed language from its contracts with the private insurers that wrote the federal NFIP policies that prohibited them from offering other flood-insurance products.57

Related Read

The Flood Insurance Fix

Ideally, flood insurance would be provided by the private market, with actuarially sound rates that would discourage building in flood-prone areas.

Arbitraging National Flood Insurance Program Cross Subsidies

One reason that private insurers are interested in offering flood insurance is the cross subsidies within the federal program. Originally, the subsidies for pre-FIRM structures were supposed to come from taxpayers explicitly through appropriations, but that system was replaced with cross subsidies from new structures to old—that is, post-FIRM structure owners continue to pay a de facto “tax” as part of their premiums to cover pre-FIRM structures.58 And, as described earlier, some newer structures that undergo transitions from the A zone to V zone or BFE are also cross subsidized.

Private insurance allows those who would be overcharged in the federal program to escape from paying this additional fee. A modeling exercise that examined premiums for single-family homes in Louisiana, Florida, and Texas suggested that 77 percent of single-family homes in Florida, 69 percent in Louisiana, and 92 percent in Texas would pay less with a private policy than with the NFIP; however, 14 percent in Florida, 21 percent in Louisiana, and 5 percent in Texas would pay more than twice as much (see Figure 3).59

Cross subsidies work only if entry is restricted, thus forcing people to pay the extra money.60 The most famous example of this is the telephone cross subsidies from long distance to local service back in the days of the AT&T monopoly. Long-distance rates were set far above cost in order to keep local calling prices below cost. The entry of MCI into long-distance telephone service allowed callers to escape this extra charge, which ultimately led to the breakup of AT&T and the end of the cross subsidy.61 The decision by Congress to expose federal flood insurance to private alternatives likewise reveals—and eventually should eliminate—the cross subsidies.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has responded to private flood insurance with proposed revisions to its premium schedule to price the risk of its individual policies more accurately. Currently, NFIP rates are not finely tuned, meaning that they only roughly reflect the risk posed by a particular property. They vary only by zone (A or V) within the Special Flood Hazard Area and with structure elevation above the BFE.

As the Congressional Research Service explains in a 2021 report:

For example, two properties that are rated as the same NFIP risk (e.g., both are one-story, single-family dwellings with no basement, in the same flood zone, and elevated the same number of feet above the BFE), are charged the same rate per $100 of insurance, although they may be located in different states with differing flood histories or rest on different topography, such as a shallow floodplain as opposed to a steep river valley. In addition, two properties in the same flood zone are charged the same rate, regardless of their location within the zone.62

In contrast, “NFIP premiums calculated under [a proposed new risk assessment formula] Risk Rating 2.0 will reflect an individual property’s flood risk” using historical flood data, as well as commercial catastrophe models.63

The political system has resisted FEMA’s attempts to rationalize the rate structure.64 The new rates were supposed to take effect in October 2020, but the Trump administration delayed implementation until October 2021 (after the 2020 presidential election). Now Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D‑NY) is obstructing the new rates because of the implications for his constituents on Long Island, where some rates could increase by 500 percent over time. This current rate structure is allowing private insurers to cherry-pick NFIP insureds and offer lower rates to those property owners who are cross subsidizing the riskier properties. Over time this will eliminate the cross subsidizing of some NFIP insureds, resulting in higher prices for Schumer’s constituents on Long Island and other properties. Given the politics of disaster relief, this will likely result in explicit subsidies from taxpayers to the owners of flood-damaged waterfront properties, probably in the form of bailouts following large disasters—in essence, a return to pre-1968 flood policy.

So, some portion of private retail flood insurance in the United States is the result of cross subsidies within the current FEMA system. Once those subsidies are eliminated by private competition, FEMA policies allegedly will consist only of explicitly subsidized policies, which will be of no interest to private insurers, and the more-or-less actuarially fair policies that private insurers presumably could take over. Once policies whose excessive charges paid for the cross subsidized policies are eliminated, only two types of policies will remain: the explicitly subsidized policies on structures that were built before flood maps, and the remainder, which are charged actuarial rates that cover expected losses. Those latter policies could presumably be privatized.

But cross subsidies do not explain the existence of private flood reinsurance, which is the private insurance that insurers purchase for themselves to ward against large losses. Private flood reinsurance not only exists, but FEMA itself purchases it. Since 2017, the agency has purchased reinsurance for claims that total between $4 billion and $10 billion per year, with taxpayers then acting as the reinsurers for even higher losses.65

The existence of private flood reinsurance suggests that those insurers are not concerned about Kousky and Cooke’s worst-case scenario of a fat-tailed Pareto distribution with tail dependence for flooding.

Conclusion

Federal flood insurance arose as a policy device with two purposes: to reduce the use of post-disaster congressional appropriations for disaster relief and to impose the cost of rebuilding on the owners through premiums. This has been partially successful. The percentage of pre-FIRM structures receiving subsidized coverage has fallen from 75 percent in 1978 to 13 percent in 2018.

But some degree of taxpayer subsidy remains, and has recently grown. After Hurricane Sandy and subsequent FEMA flood map updating, Congress protected owners from rate increases by grandfathering structures so that they now pay rates that are below actuarially fair levels in relation to the specifics of their flood zones and the degree to which they are elevated above the floodplain. Moreover, enforcement of the elevation requirement is spotty at best.

The appearance in recent years of private flood insurance may seem to be a hopeful sign that federal flood policy is moving toward something more consistent with the nation’s ethos. However, these insurers’ entry into the market appears to be the product of cross subsidies within the federal program, not an overall move to replace government protection with private insurance coverage. Once the overcharged properties have largely been moved out of the NFIP and in to private coverage, the remaining policies will likely be explicitly subsidized—either with direct aid following a disaster or with government subsidies to purchase private insurance. It is unclear whether that would be better than the current system.

The existence of private flood reinsurance suggests that claims about the impossibility of private provision of flood insurance are incorrect. But even if that’s true, there is still the question of whether property owners who currently receive cross subsidies for their waterfront properties are willing to pay actuarially fair rates—and what happens if they do not and then are struck by floodwaters.

The NFIP raises other important policy questions. Is the 50 percent “substantially damaged and substantially improved” trigger the right threshold to require property owners to elevate their buildings above BFE? What should be done about the poor enforcement of the BFE requirement?

There is also the question of what—if anything—to do about structures that predate federal flood insurance, do not have mortgages, and do not purchase federal flood insurance. Ideally, these structures should present no policy problems at all: their owners are neither asking for nor receiving subsidy and are bearing the cost of their risk taking; moreover, the emergence of a private flood insurance market may provide them with products that they do find attractive. If neither they nor policymakers are time-inconsistent on this arrangement, these property owners should be allowed to continue to choose and bear flood risks. But even they receive indirect subsidy through federal grants for local infrastructure following disasters.

In short, the NFIP was an important decision by Congress to move away from providing ad hoc disaster aid to flood victims at taxpayer expense. But lawmakers’ commitment to a subsidy-free system has been imperfect from the beginning, and they have backslid further from that in recent years. The NFIP needs to reembrace the goal of insureds paying actuarially fair premiums. Hopefully, the recent appearance of private flood insurers in the marketplace will help with this and not merely cherry-pick cross subsidies in the current system. More hopefully, these private insurers will not suffer the financial wipeout that felled their predecessors a century ago.

Citation

Van Doren, Peter. “The National Flood Insurance Program: Solving Congress’s Samaritan’s Dilemma,” Policy Analysis no. 923, Cato Institute, Washington, DC, March 2, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36009/PA.923.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.