This article is condensed from their paper, “The Perverse Effects of Subsidized Weather Insurance,” forthcoming in the Stanford Law Review, Vol. 68.

Catastrophes from severe weather are perhaps the costliest accidents humanity faces. While we are still a long way from technologies that would abate the destructive force of storms, there is much we can do to reduce their effect. True, we cannot regulate the weather, but through smart governance and correct incentives we can influence human exposure to the risk of bad weather. We may not be able to control wind or storm surge, but we can prompt people to build sturdier homes with stronger roofs far from floodplains. We call these catastrophes “natural disasters,” but they are the result of a combination of natural forces and, we show here, often imprudent and shortsighted human decisions induced by questionable government policies.

Regulating weather risk is an increasingly urgent social issue. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012 brought unprecedented property damage to the Gulf and coastal northeastern states. As a result of an enormous development enterprise, the majority of Florida real estate now lies in coastal areas affected by hurricane activity. And the potential rise of sea level and the resulting erosion of the coastline are putting at risk large chunks of prime real estate in numerous regions.

Our thesis is simple: the most effective way to prepare for storms is through disaster insurance. But this preparation would not simply take the form that is commonly thought: insurance as a form of post-disaster relief. Rather, we see insurance as a form of private regulation of safety—a contractual device controlling and incentivizing behavior prior to the occurrence of losses.

Buying insurance is a transaction in which policyholders are prompted to adopt loss mitigation measures. Insurance contracts attach prices to risky behavior and thus force insurance buyers to factor the risk into their decision. Homeowners’ property insurance, by pricing the cost of choosing to live in the path of storms, sends a crucial price signal that could be a key ingredient in driving community development and individual location decisions.

Unfortunately, in the United States, insurance is denied its potential role as an efficient regulator of pre-storm conduct. It does not give people price signals regarding the cost of living in severe weather regions and it does not induce rational community development and infrastructure investment. American insurance fails to achieve those straightforward and enormously important roles for a simple reason: it is provided by the government in a subsidized manner. Insurance premiums are deliberately suppressed—often dramatically so—thus failing to alert private parties who purchase property insurance to the true risk of living dangerously. It allows those private parties to (rationally) assume excessive risk and dump the cost of their coastal living upon taxpayers. We argue that much of the development of storm-stricken coastal areas is due to insurance subsidies and would not be justified otherwise.

This is only the first part of the bad news. There is more, and it gets uglier. Public debates over subsidized weather insurance often ignore the over-development and excessive risk distortion, because they focus on a myth: the myth that insurance must always be affordable. Subsidies are necessary, policymakers have told us repeatedly, because they help support low-income and working-class people who might otherwise be unable to afford insurance and would not be able to remain in their homes. Subsidizing weather insurance is “our moral duty to the poorest people and working people and lower middle income people,” in the words of then-congressman Barney Frank (D–Mass.). The subsidies prevent “working families who are doing everything they can to put food on the table” from losing their homes, according to Sen. M. K. “Heidi” Heitkamp (D–N.D.). The subsidy, in other words, is thought to promote a redistribution that benefits economically weak populations.

We have long suspected that this justification is false. Our suspicion rested on the puzzling differential treatment of hurricanes versus tornados. These two types of severe storms cause similar aggregate magnitudes of property destruction, but federal subsidies apply to flood losses caused by hurricanes, not to wind losses caused by tornadoes. This was puzzling because hurricane victims live closer to water than tornado victims, and it is generally known that living close to water is a privilege of the affluent. This pattern seemed inconsistent with the affordability-of-insurance rationale. We therefore studied the insurance data and we now have evidence that the weather insurance subsidy scheme is indeed a boon to the elite; a redistribution in favor of the wealthy. We present this new evidence here.

Our study, and in particular our findings regarding the myth of affordability, are intended to shed light on recent legislative activity, which unfortunately only made things worse. In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy and the enormous bill that the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency—the agency that administers the federal subsidies for flood insurance—had to foot, Congress with bipartisan support enacted the Biggert–Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012. It intended to scale back the subsidies and had the potential to provide better incentives for human preparedness for floods.

But Congress did not let this laudable new statute live long enough to do any good. Immediately after it was enacted, subsidy recipients—now scheduled to lose their subsidies—protested. Congress quickly reacted—again, with a rare showing of bipartisan consensus—enacting what amounts to almost a full repeal of the 2012 reform. The Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 restored virtually all of the federal subsidies and cross-subsidies for flood insurance. Our results show that the rhetorical premise invoked by supporters of this act—that hard-working low-income people need it to keep their homes—is misguided. The beneficiaries of weather insurance subsidies are not low-income folks.

The Existing Subsidy Scheme

Historically, flood risks were covered through private insurance, if policyholders purchased it as an added coverage, priced separately from the basic homeowners policy. But many property owners opted not to purchase the flood coverage, political and public pressure often led to the federal government providing post-disaster relief, and some floods were simply mind-bogglingly large, producing wide-scale flood-related losses. Those realities led Congress to create the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Through it, the federal government underwrites flood insurance policies at rates that are set by FEMA and subsidized by the Treasury Department. Of course, in the presence of such subsidized options, private companies cannot compete in this niche, and government-provided flood policies dominate the market.

The goal of the NFIP was to condition participation in the subsidized program on communities’ adoption of floodplain management ordinances that reduce future flood risks to new construction. Congress also made the purchase of NFIP policies mandatory for properties that are in certain flood zones and that are subject to federally regulated mortgages. But the rates charged by NFIP to its policyholders violate basic insurance fundamentals. First, they are based on flood maps that are often out of date. Second, property owners in high-risk areas pay well below actuarial rates. And third, political influence, rather than market forces, shapes the process of characterizing particular areas as flood-prone and eligible for subsidies.

The NFIP has been operating at a massive deficit, estimated in 2012 to be around $24 billion. That prompted lawmakers to enact the Biggert–Waters Act, initiating a gradual elimination of the subsidies. The act was designed to phase out the subsidies entirely for certain “repetitive loss properties,” second homes, business properties, homes that have been substantially improved or damaged, and homes sold to new owners. It also permitted a faster pace of rate increases (25 percent annually, up from the previous 10 percent rate hike cap).

However, the backlash from property owners along coastal areas, where resulting premium increases were the greatest, was swift and effective. In some areas, there were reports of homeowners’ premiums rising 10-fold. The concern expressed by many lawmakers, on behalf of their angry constituents, was that unless the new law was repealed, people wouldn’t be able to remain in their homes.

The political pressure was so successful that even Rep. Maxine Waters (D–Calif.), one of the co-authors of the 2012 legislation, voted in favor of repealing it. In 2014, Congress passed the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act, which largely restored the old subsidy scheme. For example, the new law also called on FEMA to keep premiums at no more than 1 percent of the value of the coverage, which in many flood territories is dramatically below true risk.

Wind insurance / Another category of large-scale, government-sold insurance for weather risk includes state-owned insurance corporations that specialize in wind-damage coverage. Most prominent among them is Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, which provides the vast majority of the wind insurance for properties on the coast of Florida.

Like a private insurance company, Citizens prices its policies based on risk. It divides the state into 150 geographic rating territories and sets its rates based on weather patterns, construction methods, and past losses in each territory. But there is one big difference compared to private insurance. Like the premiums charged for flood coverage at the federal level by NFIP, the premiums Citizens collects from Florida policyholders are far below what is necessary to cover the full risk, and are politically mandated to be so (as state regulations limit Citizens’ ability to raise rates). Citizens does not face the same loss constraints that private insurers do; if the premiums are not enough to pay for the wind damage, Citizens can cover the shortfall by passing it on to Florida’s taxpayers.

Affordability?

The subsidies embodied in government insurance are an intended feature because they are thought to favor economically weak homeowners; they are definitely not thought to be a bailout for the rich. “This is not about the millionaires in mansions on the beach…. These are middle-class, working people living in normal, middle-class houses doing their best to raise their kids, contribute to their communities, and make a living,” explained then-senator Mary Landrieu (D–La.). This perception explains why even people not affected by weather insurance subsidies (but who, perhaps unbeknownst to them, pay taxes to fund them) strongly support the subsidies. In one survey, only 15 percent of unaffected Florida citizens supported the premium increases.

The cross-subsidy created by government-sold insurance follows, then, a distinct logic: it moves from people lucky enough to live in safe areas (“the affluent”) to the less lucky residents living in low-lying areas in storms’ paths (“the poor”). But this conjecture, that subsidized flood insurance benefits the less affluent, had not been tested. We long believed that it is wrong and that the opposite is true: the subsidy accrues primarily to the affluent. This, for a simple reason: those who need flood insurance most are the habitants of properties build in proximity to the coast, where severe weather strikes most forcefully. You don’t need to be a real estate economist to know that people pay a premium to live close to the water. Are we really asking middle-class taxpayers to subsidize beachfront property owners, all in the guise of “affordability”?

To test this hypothesis, we examined Florida’s wind-peril insurance policies, which are sold and subsidized by the state-owned Citizens. Those data include information about each individual policy and the actual premium charged. Also, by state law, the data have to include an exact estimate of the subsidy enjoyed by each policyholder—namely, how much more Citizens would need to charge this policyholder to bring the premium to its hypothetical true risk level, which would not require a subsidy from the state.

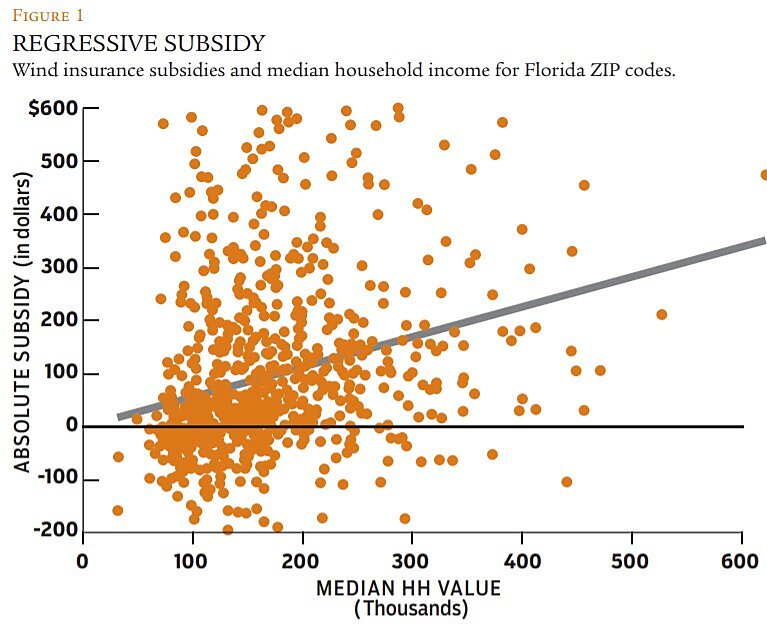

We wanted to see where the subsidies are concentrated. Do they accrue to wealthier households? For that, we used two proxies for household wealth. (Citizens’ data do not include personal identifiers and thus could not be matched with any direct measure of wealth.) The first measure is Household Value: knowing the ZIP codes of the insured properties, we were able to examine whether subsidies are correlated with median household value within the ZIP code. The second measure is Coverage Limit: knowing the amount of insurance purchased under each policy, we could use that as a measure of the property’s value.

The first thing our tests showed was that higher-wealth ZIP codes in Florida are the beneficiaries of higher subsidies. Figure 1 offers a scatterplot of the trend.

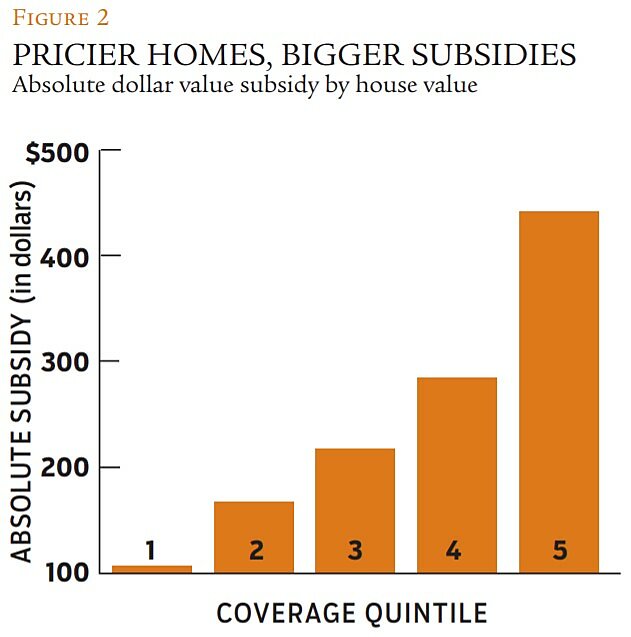

A similar picture emerges if we look at policy level data and ask whether high-value policies (those attached to high-value homes) receive a higher or lower subsidy. We divided Citizens’ policies into five quintiles according to the policy coverage amount. For each quintile, we calculated the average subsidy. In Figure 2 we see a clear picture: higher quintiles of wealth get a higher absolute subsidy.

These visual tests were complemented by regression analysis, and the results were striking: A 1 percent increase in the Coverage variable is associated with a 1.052 percent increase in the subsidy. Simply put, if property A is worth twice as much as property B, and thus the owner of property A purchases coverage that is 100 percent greater than the coverage purchased by the owner of property B, the owner of A enjoys on average a 105 percent higher absolute subsidy. These results are highly statistically significant and were replicated in various specifications of the statistical model.

The bottom line is clear: the wind insurance subsidies within Citizens’ policies accrue disproportionately to affluent households and the magnitude of this regressive redistribution is substantial. While we are unable to measure directly the wealth of policyholders, we showed that people who buy higher coverage (namely, who own more expensive homes)—or, alternatively, people who live in wealthier ZIP codes—receive larger subsidies, both in absolute magnitude and as a percentage of their premium.

The estimates we derived for the correlation between wealth and subsidy probably understate the true magnitude of the pro-affluent advantage. First, one of our measures of wealth—the policy coverage limit—is capped by Citizens’ rules, which means that we are not measuring the true wealth of the people who buy maximal coverage, and thus we are deriving downward-biased correlations. Second, Citizens’ report of the subsidies—the indicated rate changes—understates the subsidies’ true magnitude. Citizens does not take into account some of the costs of providing insurance—costs that private insurers would incur in running an insurance scheme. Specifically, when Citizens calculates the amount of the indicated rate change, the insurer does not build into the new rate the cost of reinsurance—an insurance reserve necessary to protect it against the risk of pricing errors or unexpected spikes in losses. Citizens does not need such a reserve because of its power, in effect, to tax the citizenry or to assess all insurance purchasers in the state of Florida.

We have not tried to identify the causal story underlying this correlation, nor are we interested in its direction. Causation may go either way: greater wealth may help people secure greater subsidies, or greater subsidies may help people move into more expensive homes. We are not interested in causation because the troubling feature of the system has nothing to do with any causal theory. The problem is the large positive correlation between wealth and subsidy—a correlation that conflicts with the goals and underlying rhetoric justifying the program.

We have strong reasons to believe that a similar pattern occurs under other government weather insurance subsidies, like the federal flood insurance program. People insured by the NFIP pay only a fraction of the full-risk premium. In 2006, FEMA estimated this fraction to be 35–40 percent. Estimated by the Congressional Budget Office, an average premium charged by the NFIP was $721, but would cost $1,800–$2,060 without subsidy. CBO also found that “properties covered under the NFIP tend to be more valuable than other properties nationwide.” While the median value of a U.S. home that year was $160,000, the median value estimated for homes insured by the NFIP ranged from $220,000 to $400,000. The CBO found that “much of the difference is attributable to the higher property values in area that are close to water.” There are 130 million homes in the United States, but only a small fraction of them receive subsidized NFIP policies. Of those that do, nearly 80 percent are located in counties that rank in the wealthiest quintile.

Despite the image—often invoked in political debates over flood insurance—of the subsidy going to struggling middle-class homeowners who have lived for generations in floodplains, the reality is different. The CBO found that 40 percent of the subsidized coast properties in the sample are worth more than $500,000; 12 percent are worth more than $1 million. These are far higher proportions than in the rest of the country. For inland properties (the great majority of which do not purchase flood insurance), only 15 percent are worth more than $500,000 and only 3 percent more than $1 million.

The myth of the subsidized struggling homeowner is further dispelled by another striking fact: 23 percent of subsidized coastal properties are not the policyholders’ principal residence—they are either vacation homes or year-round rentals. Some 47 percent of the subsidized homes that are not principal residences are worth more than $500,000 (and 15 percent are worth more than $1 million).

Investment Distortions

Our discussion so far shows that government insurance produces undesirable distributive effects: the benefits of the programs flow disproportionately to the affluent. But there is another troubling distortion of the existing government insurance programs: the effect on total welfare. The primary distortion is the location of communities: too close to the path of storms.

Insurance, if priced accurately, provides an important service of signaling to people the risk cost of living near water. This is a general (desirable) feature of insurance, operating in effect like a Pigouvian tax in internalizing an otherwise overlooked cost, helping to make an informed cost-benefit calculation in choosing locations. Subsidized insurance rates destroy the information value of full-risk premiums, thus suppressing the true cost of living in severe weather zones and creating an excessive incentive to populate attractive but dangerous locations.

Underpricing flood insurance in coastal areas has long been associated with (and likely contributed to) excessive private development of flood zones. We know, for example, that the damage costs of hurricanes have increased dramatically over the past generation. But strikingly, much of the upward trend in storm loss data, after careful adjustment for societal factors, can be explained not by weather fluctuations, but rather by increased concentration of property in dangerous areas.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of people living in coastal areas in Florida increased by 10 million—almost fourfold—between 1960 and 2008. Coastal exposure now represents 79 percent of all property exposure in Florida, with an insured value of $2.8 trillion (in 2012). Major hurricanes did nothing to stop this migration. It is estimated that since Hurricane Andrew struck the Florida coast in 1992, development more than doubled the property value on its path. According to the Government Accountability Office, the $25 billion in total economic losses Andrew caused in 1992 would have resulted in more than twice that amount—$55 billion—were it to have occurred in 2005.

Despite the image that storm insurance subsidies go to the middle class, 40 percent of insured coastal properties in a CBO sample were worth more than $500,000 and 12 percent were worth more than $ 1 million.

The effect of the government insurance subsidy on homeowners’ location decisions can be further captured by the following finding: According to the Heinz Center for Science, Economics, and the Environment, in some of the areas closest to the shoreline, annual insurance rates have to be set at a whopping $11.40 per $100 of coverage to meet the risk projections. That’s over 10 percent of property value each year! At the same time, a survey of homeowners found that participation in insurance schemes with such high premiums would be “quite low”—about half of flood policyholders are only willing to pay $1–$2 per $100 of annual insurance coverage.

Not surprisingly, given the substantial subsidy provided by NFIP insurance and the increased development along coastal areas, the number of policies issued by NFIP increased in the past generation from 1.9 million to over 4.6 million. Some of those policyholders have lived in the area long before the NFIP, but many are newcomers, representing a repopulation enterprise facilitated by distorted insurance contracts. In the absence of subsidized premiums, many of these newcomers would not have moved to their present high-risk location or would not have paid the current high prices for the property. Indeed, one of the major complaints of existing homeowners against the Biggert–Waters Act was that they were unable to afford the new premiums and the new premiums were “scaring the bejesus out of people,” making mortgage loans unaffordable and driving away potential buyers.

The End of Government Weather Insurance?

In delivering a subsidy that private insurance does not give, government insurance inflicts two distortions: regressive redistribution and inefficient investment in residential property. Those distortions are not inherent to the function of insurance. They can be attenuated, and perhaps solved, by a return to private insurance markets.

Is there a market failure in property insurance markets justifying government takeover? It is unlikely that people underappreciate the need for such insurance, given the salience of weather catastrophes. It is possible that some people truly cannot afford flood or wind coverage, relying instead on post-disaster relief. But that is hardly a justification for the existing government-run insurance programs. Instead of being the provider of insurance, the government can simply mandate flood insurance in areas where some costs are otherwise shifted to the public (as it does for homes with federally guaranteed mortgage loans). Or it can direct subsidies only to the truly needy.

And if private markets turn out not to have the capacity to cover all of the flood and wind risk that would be left uncovered should all the current government subsidies be repealed wholesale, a much more effective form of subsidy would be something along the lines of the recently renewed Terrorism Risk Insurance Act. Under such a regime, the federal government would play the role of reinsurer of last resort, leaving the private market to cover all losses up to a very high trigger point, which could be in the tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars.

We can end this article with a call for ending government-run weather insurance, replacing it with pinpointed, need-based subsidies. This would eliminate the inefficient incentives to develop and redevelop coastal land, as well as the regressive redistribution. But where is the sense in such a naive proposal?

Congress did enact a law to eliminate the flood insurance subsidies—a bipartisan law remarkably passed in the peak days of partisan gridlock—only to quickly toss it out in favor of an even more widely supported bill reinstating the subsidies. Insurance affordability, it turns out, is one of the most effective political calls to arms, in this case resulting in a premium scheme that will likely remain in place for decades. We can only contribute to clarifying its enormous social cost.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.