This week saw the passing of “Equal Pay Day,” which marks the culmination of the roughly three extra months that an average female employee had to work in 2019 to match the amount of money made by an average male worker in 2018. Many people see the pay gap as unjust, but is it really a result of rampant sexism in the workplace as the critics allege?

A survey unveiled on Tuesday by CNBC and Survey Monkey suggests that, actually, both men and women are equally pleased with their employment situations and the earnings gap can largely be explained by women being more likely on average to choose part-time work.

“Men have a Workplace Happiness Index score of 72 and women a score of 70, close enough to lack a statistically meaningful difference,” according to the newly released data. That fits with earlier polling that was conducted by Cato’s Dr. Emily Ekins, which found that in the United States, the vast majority of women “believe their own employers treat men and women equally.” Fully 86 percent of women polled believed that their employer pays women equally.

There is still a pay gap between men and women who work full-time, but that may be partly due to men and women opting to work in different fields. Dangerous jobs in fields like mining and fishing, for example, tend to attract men. Those jobs also tend to be relatively well-remunerated. (As HumanProgress.org advisory board member Mark Perry points out, the gender gap in workplace deaths far exceeds the gap in pay).

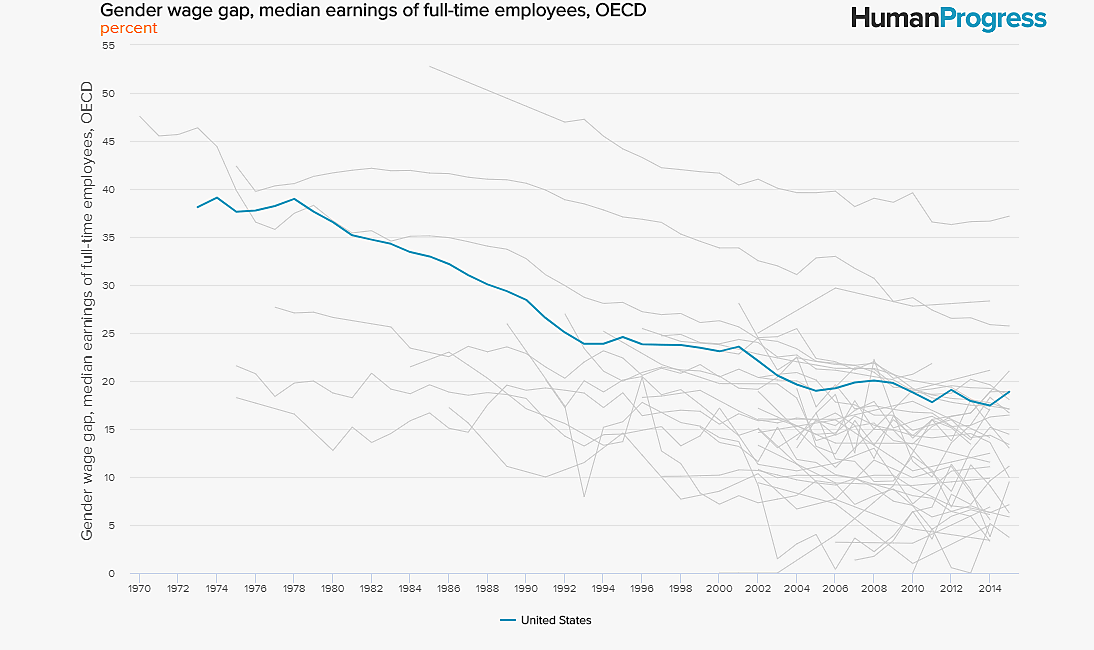

Even so, among full-time workers, the “pay gap” is rapidly narrowing. Data from the OECD shows that the gender wage gap in median earnings of full-time employees is declining in practically all countries for which there are data. In the United States, highlighted in blue in the graph below, the wage gap has fallen dramatically since the 1970s. In 1975, the U.S. gender wage gap was 38 percent. By 2015, it had shrunk to 18 percent.

That 18 percentage point difference does not take into account important characteristics like “age, education, years of experience, job title, employer, and location,” according to my Cato colleague Vanessa Calder. A recent study, which controlled for those characteristics, concluded that the U.S. gender pay gap is only around five percent, meaning that Equal Pay Day should actually be in January.

Of course, if any of that small remaining five percent gap is the result of sexist discrimination—rather than additional mitigating factors that the study failed to control for—then that is unacceptable. We should denounce all forms of inequitable treatment, wherever it persists. We should also take a clear-eyed view of the data and recognize the remarkable gains women have made in the workplace—and how labor market participation has transformed women’s lives for the better.