A common refrain in opposition to school choice is that choice is rooted in racial segregation. Specifically, that people barely thought about choice until the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision required public schools to desegregate, and racists scrambled to create private alternatives to which they could take public funds. I have dealt with this before and won’t rehash the whole response (hint: Roman Catholics), but a new permutation popped up on Vox yesterday, with author Adia Harvey Wingfield asserting:

Prior to Brown v. Board of Education, most US students attended local public schools. Of course, these were also strictly racially segregated. It wasn’t until the Supreme Court struck down legal segregation that a demand for private (and eventually charter and religious parochial) schools really began to grow, frequently as a backlash to integrated public institutions.

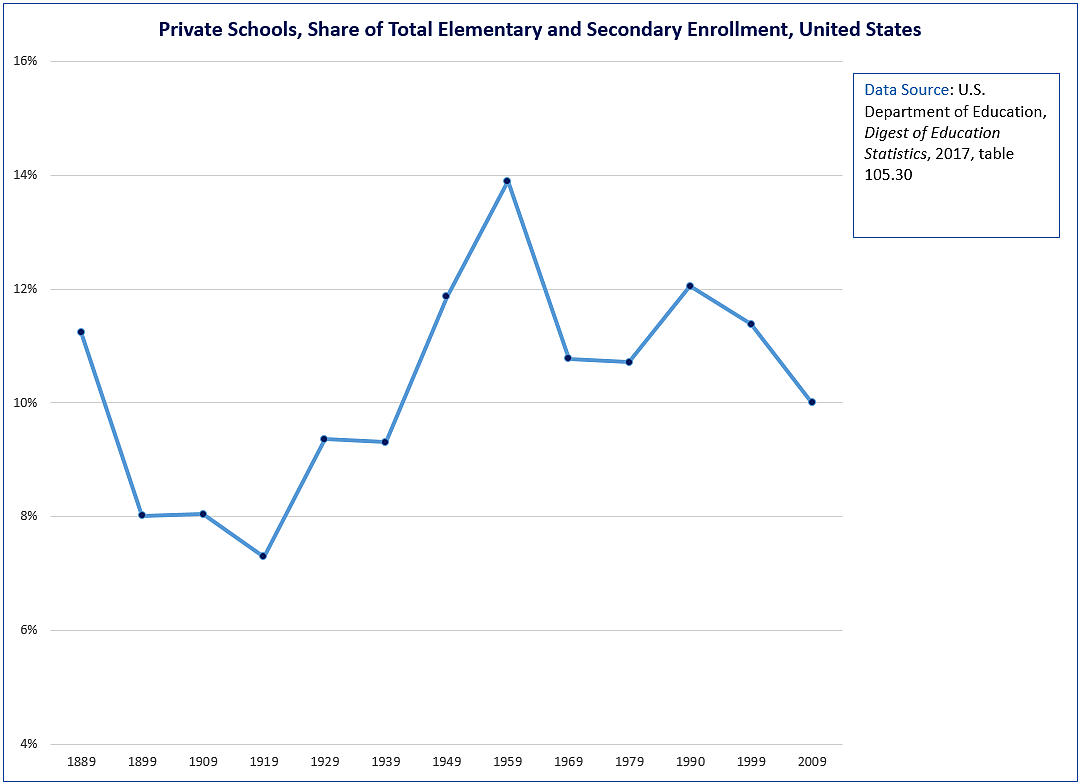

Kudos to Prof. Wingfield for making clear that many public schools were “strictly racially segregated,” which often seems to be soft pedaled when linking choice to segregation. But her assertion that private schooling didn’t “really” begin to grow until after Brown is not borne out by the data. As the chart below shows, while the share of enrollment in private schools spiked in 1959, the growth in private schooling didn’t suddenly increase right before that. In 1889—the earliest year available— the private school share was 11 percent, dipping to 7 percent in 1919, then pretty steadily rising until the 1959 peak. (Note, the earlier years of the federal data are in ten-year increments. Also, data include pre‑K enrollments.)

History is clear that private education has long been with us, and while it has certainly at times been used to avoid racial integration, it has also been employed for reasons having nothing to do with that. This remains true even in our relatively modern era in which “free” public schools have crowded out many private options.