Uwe Reinhardt, a beloved health economist at Princeton University, died Monday at the age of 80. Uwe was a giant in his profession. His combination of insightful economic analysis and wit knew no equal. I always, always looked forward to hearing what Uwe had to say. We are proud to have hosted him at the Cato Institute, to have debated him, and to have called him a friend. The Cato Institute offers its condolences to the Reinhardt family, for whom Uwe made no secret of his love, and to all those in the health policy and economics professions who will miss him dearly.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Feds Should Ask Tech Innovators to Seek Forgiveness, Not Permission

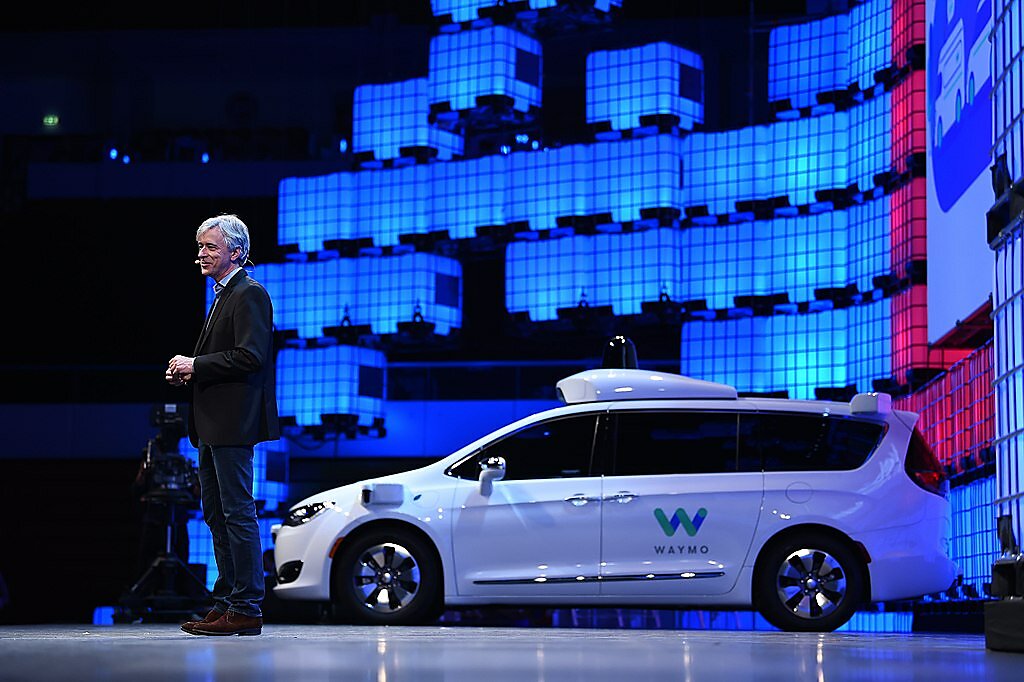

A fleet of driverless cars designed by Waymo, a project of Google’s parent company, Alphabet, is on the roads of Phoenix, Arizona. Last week, Waymo CEO John Krafcik announced that in the coming months the driverless cars will be part of the world’s first autonomous ride-hailing service. The recent news is a milestone in driverless car technology history, and it’s no exaggeration to claim that the technology behind these new cars has the potential to save hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of lives in the coming decades. Sadly, drones, another life-saving technology, have had a tougher time getting off the ground.

Waymo’s cars are not suddenly arriving on the scene. Google has been working on getting a driverless car on the road since 2009, and Waymo has been offering some lucky passengers in the Phoenix area rides since April. However, these cars had a driver at the wheel, just in case. The fleet now driving in Phoenix does not include safety drivers.

This may prompt unease among some Phoenix residents. A clear majority of Americans are uncomfortable about getting into driverless cars. Yet human drivers are deadly. More than 90 percent of car crashes can be attributed to human error, and motor vehicle accidents killed an estimated 40,200 people on American roads last year.

Fortunately, the life-saving potential of driverless cars seems to have been a persuasive selling point to lawmakers and regulators. This is in part because of their massive unrealized benefits, but also because auto-safety regulators tend to allow car manufacturers to get their product on the market after certifying that they’re in compliance with safety standards, relying on recalls if and when safety standards are violated, as Ars Technica technology reporter Timothy Lee explained:

Another important factor is that auto-safety regulators have a tradition of being relatively deferential to car companies. Agencies like the Food and Drug Administration require companies to seek pre-market approval for their products. By contrast, the approach of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is to set out general guidelines requiring features like airbags and antilock brakes and then ask automakers to self-certify their compliance. NHTSA then relies on after-market recalls to deal with vehicles that turn out to be defective.

This approach creates a somewhat greater risk of defective products reaching the marketplace. But it also enables automakers to get potentially lifesaving innovations into the marketplace more quickly. And carmakers are large, bureaucratic organizations that have strong incentives to color inside the lines, so there’s not much reason to worry about small, fly-by-night manufacturers sneaking defective products into the marketplace.

We shouldn’t forget that the technology will improve lives as well as save them. For the elderly and the disabled, driverless technology offers the chance to vastly improve mobility. In fact, last year Google’s driverless car drove a blind man, Steve Mahan, in Austin. According to Mahan, “This is a hope of independence. These cars will change the life prospects of people such as myself. I want very much to become a member of the driving public again.” Parents with children busy with after-school activities will also undoubtedly benefit from the kind of driverless ride-hailing service Waymo plans to offer.

Driverless cars are not the only emerging technology that could save and improve lives. Sadly, however, these other products are governed by a tougher regulatory framework than that overseeing Waymo’s cars.

Amazon’s experience with drones has been off to a difficult regulatory start. The Internet giant, which is interested in developing delivery drones, went to England to conduct its first drone-delivery test last year. This was despite the fact that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced drone delivery plans as far back as 2013 and applied for permission from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to test drones in 2014. That same year, the AP noted that other countries were outpacing the United States when it came to drone regulation:

The Federal Aviation Administration bars all commercial use of drones except for 13 companies that have been granted permits for limited operations. Permits for four of those companies were announced Wednesday, an hour before a hearing of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s aviation subcommittee. The four companies plan to use drones for aerial surveillance, construction site monitoring and oil rig flare stack inspections. The agency has received 167 requests for exemptions from commercial operators.

Several European countries have granted commercial permits to more than a 1,000 drone operators for safety inspections of infrastructure, such as railroad tracks, or to support commercial agriculture, Gerald Dillingham of the Government Accountability Office testified. Australia has issued more than 180 permits to businesses engaged in aerial surveying, photography and other work, but limits the permits to drones weighing less than 5 pounds. And small, unmanned helicopters have been used to monitor and spray crops in Japan for more than a decade.

By the time the FAA approved Amazon’s drone it was already obsolete and out of date, with Amazon testing a more advanced drone. Amazon’s vice president of global public policy told the Senate Subcommittee on Aviation Operations, Safety, and Security in 2015, “Nowhere outside of the United States have we been required to wait more than one or two months to begin testing.”

Like driverless cars, drones are potentially life saving, with firefighters, emergency medical technicians, and building inspectors—among many others—standing to benefit from their use. Zipline, a California-based company that makes medical delivery drones, was founded in 2014. And yet, Zipline co-founder and chief executive Keller Rinaudo noted in August that, despite being based in California, Zipline had not flown any flights in the United States.

By September of this year, Zipline had flown “1,400 flights and delivered 2,600 units of blood” in rain and high winds in Rwanda.

Amazon Prime Air, by comparison, is much more restricted:

We are currently permitted to operate during daylight hours when there are low winds and good visibility, but not in rain, snow or icy conditions. Once we’ve gathered data to improve the safety and reliability of our systems and operations, we will expand the envelope.

Fortunately, the Trump administration has taken steps to allow for a more innovative drone environment, last month launching a drone program that will allow local governments and companies to experiment with drones in a more relaxed regulatory environment.

Regulatory agencies should take an approach that allows companies to ask for forgiveness rather than permission, an approach laid out by Mercatus’ Adam Thierer in his book Permissionless Innovation. When it comes to the FAA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for instance, the approach is the reverse. Almost four years ago, the FDA shut down the personal genome testing company 23andMe after it marketed its saliva collection kit “without marketing clearance or approval.” In its letter to 23andMe, the FDA did not cite any 23andMe customers who had complained about 23andMe’s product.

It would be naive to think that there won’t be bumps in the road as more driverless cars take to the streets. For example, driverless cars could prompt regulatory fights between states and the federal government, although House and Senate driverless car legislation contain identical provisions that seek to address preemption concerns. There are also issues related to cybersecurity and insurance, but we shouldn’t forget that profit-maximizing firms have incentives to not kill or injure their customers.

Regulatory reform concerning new and emerging technology is long overdue. 3D printing, the “Internet of Things,” drones, driverless cars, and robotics, are only some of the exciting new technologies and fields that hold the potential to enrich and save lives. These benefits will be sooner realized if regulators set innovators free. The ubiquity of driverless cars won’t make the world perfect, but it will make the world better.

Related Tags

Can the WTO Handle China?

We often hear arguments that the World Trade Organization cannot handle an economy like China’s, with its heavy state intervention. Trade rules are just not up to this task, some people say. Here’s a recent example from a Wall Street Journal article entitled “How China Swallowed the WTO”:

Rather than fulfilling its mission of steering the Communist behemoth toward longstanding Western trading norms, the WTO instead stands accused of enabling Beijing’s state-directed mercantilism, in turn allowing China to flood the world with cheap exports while limiting foreign access to its own market.

“The WTO’s abject failure to address emerging problems caused by unfair practices from countries like China has put the U.S. at a great disadvantage,” Peter Navarro, a trade adviser to President Donald Trump, said in an interview.

China has a wide range of policies that make up its industrial policy, and we can’t address them all in a short blog post. However, we will describe one recent example, and explore briefly whether WTO rules can help. This is also from the WSJ:

Batteries have emerged as a critical front in China’s campaign to be the global leader in electric vehicles, but foreign auto makers and experts say it is rigging the market to favor domestic suppliers.

Tianjin Lishen Battery Co. here in eastern China recently agreed to sell its battery packs to Kia Motors for the EVs the South Korean company makes in China and is now in talks to supply General Motors, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen, a supervisor for the Chinese company said.

But that is largely because Tianjin Lishen has little foreign competition.

Foreign batteries aren’t banned in China, but auto makers must use ones from a government-approved list to qualify for generous EV subsidies. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s list includes 57 manufacturers, all of them Chinese.

Foreign battery companies declined to discuss their absence. But analyst Mark Newman of Sanford C. Bernstein said the government has cited reasons such as paperwork errors to exclude foreign suppliers.

“They want to give their companies two to three years” without foreign competition to secure customers, achieve scale, and improve their technology, Mr. Newman said.

The ministry didn’t respond to questions.

So, if we accept the conventional wisdom, nothing can be done about this battery policy, right? There’s no way to prove that the policy is protectionist, so we just have to give up on the WTO as a solution here, right?

We disagree. In fact, the WTO has rules to deal with this exact kind of subtle, disguised protectionism. The WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures prohibits subsidies that are contingent on the use of domestic goods, even where the contingency is not specified in law. If a complainant can show that the connection between the subsidies and the use of domestic goods exists on a de facto basis, the measure will be found in violation. Whether a challenge succeeds will depend on the specific facts of the case. In the electric vehicles example described above, the complainant could look for, inter alia, evidence that the electric vehicle companies which have received subsidies only use batteries on the government list, or that they switched to using the batteries on the lists after the lists were published.

Of course, proving a case here is not going to be easy. A single WSJ article is not enough. The complainant will need to go gather some evidence and build its case. But that’s how litigation always works, and does not suggest any great flaw in the WTO.

The key point here is that what China is doing is not some novel approach to industrial policy that no one has ever seen before. Rather, it is classic protectionism that WTO litigation has handled for years. Governments do this sort of thing all the time, and many WTO cases deal with this exact kind of disguised protectionism. (As an example, in a 1999 decision examining whether certain Canadian subsidies to the aircraft industry were contingent on export, the WTO courts took into account “sixteen different factual elements” before concluding that the subsidies at issue violated the prohibition on export subsidies.) Thus, governments who are concerned with China’s policies should try to work within the WTO system to address their complaints.

Related Tags

Can Congress Constrain Trump on North Korea?

It seems President Trump has aroused heightened interest in the exercise of Congress’s constitutional powers in war and peace. In a 366–30 vote this week, the House of Representatives passed a nonbinding resolution declaring the U.S. military’s role in Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen unauthorized. That’s a start. Even more promisingly, a growing group of Senate Democrats is pushing legislation that would prohibit any use of funds for “military operations in North Korea absent an imminent threat to the United States without express congressional authorization.”

Though it merely makes more explicit something that ought to be fully understood under the Constitution, sponsors of the bill have understandable motivations here. President Trump has repeatedly claimed that he does not need Congressional authorization to initiate military action. In April, he demonstrated his commitment to this unlimited view of presidential war powers when he ordered missile strikes against a Syrian airbase in the absence of any credible claim of preemption and without legal authorization from Congress.

Two months earlier, the president gave an indication that he would not seek Congressional authorization or approval in potential military action against North Korea. In a press conference in February, when asked about it, he insisted, “I don’t have to tell you what I’m going to do in North Korea.”

In the ensuing months, the president has exacerbated the tensions between the United States and North Korea. In addition to taunting and ridiculing via his Twitter account, Trump has also made bold public threats. “North Korea best not make any more threats to the United States,” he told reporters in August, or “they will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

Adding to the heightened tensions, National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster has gone so far as to say the regime in Pyongyang is undeterrable. This is remarkably out of step with what the bulk of the academic literature says on the question, but it is also destabilizing in that the logical conclusion of such an assessment is that we must initiate a full-scale attack on North Korea. After all, if Pyongyang possesses nuclear weapons and doesn’t care about regime survival, traditional deterrence isn’t an option.

Senator Bob Corker (R‑TN), who, as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee would be the one to shepherd the legislation to a vote, said last month that Trump is treating the presidency like “a reality show,” and his rhetoric could set the nation “on the path to World War III.” To the extent that Trump’s advisors act as a check on the president’s erratic foreign policy inclinations, Corker added, they “separate our country from chaos.”

This escalatory rhetoric occurs in the context of a broad understanding that an outbreak of war on the Korean Peninsula would be catastrophic. Secretary of Defense James Mattis warned grimly on CBS’s Face the Nation that, “A conflict with North Korea would probably be the worst kind of fighting in most people’s lifetimes…it would be a catastrophic war if this turns into a combat if we’re not able to resolve this situation through diplomatic means.”

Scholarly and official estimates bear this out. Even a limited conventional strike by the United States against North Korean nuclear sites would risk an overwhelming number of casualties because Pyongyang’s likely response would be to immediately attack Seoul with the roughly 8,000 artillery cannons and rocket launchers positioned along the border capable of unleashing 300,000 rounds on South Korea in the first hour of the counterattack. The result would be massive destruction and hundreds of thousands of casualties in a matter of days.

And that’s if it doesn’t go nuclear, which it almost inevitably would if Pyongyang, fearful of its own destruction, found itself under attack by the world’s most powerful military. If the Kim regime targeted Seoul and Tokyo with just one nuclear weapon each, casualties would approach almost 7 million. And again, this would only generate additional escalation from all parties.

At this point, even the most cynical proponent of war would be hard pressed to identify what political end could possibly justify such devastation.

The bizarre thing about the focus on the military option is that there are plenty of worthwhile diplomatic options. American diplomats who have engaged in back-channel negotiations with North Koreans for years have made clear Pyongyang remains interested, so long as talks are conducted on the basis of mutual respect and mutual compromise, instead of demands for one-sided capitulation. Avenues include short-term confidence-building measures, like a “freeze for freeze” deal in which Pyongyang halts its nuclear weapons testing in exchange for a freeze of U.S.-South Korean joint military exercises, which the North sees as provocative. Grander bargains are also possible, but it requires a willingness on both sides to choose compromise and accommodation over rigidity and vainglory.

Explicit Congressional action prohibiting the Trump administration from initiating preventive war against North Korea may aid in checking executive war powers in this case. But only maybe. Much depends on whether the administration chooses to rely on unreasonably elastic definitions of the phrase “imminent threat.” And at the end of the day, legal constraints only have utility if the people subject to them respect them. Hopefully, the costs and risks associated with escalation will prove enough of a constraint.

Related Tags

College: Ragnarok

For the second week in a row, Thor: Ragnarok was the big winner at the box office, pulling in $56.6 million in North America last weekend and bringing its worldwide take to more than $650 million. Ragnarok is the mythological destruction of Asgard and the Norse gods, but in real life it has been a huge, money-making win for Marvel Studios. Meanwhile, American higher education has been declaring that it is facing its own Ragnarok in the form of the House Republican tax plan. This end time, in stark contrast to Thor: Ragnarok, will come from a distinct lack of money. As a Washington Post headline asks, is this “The Last Stand for American Higher Education?”

What the Hela?

I have qualms about some of the GOP proposals. For instance, the plan would tax “tuition discounts”—basically, prices not actually charged—for graduate students. That’s not technically income, so on normative grounds I’m not sure it should be taxed. The plan also calls for an “excise tax” on the earnings of endowments worth $250,000 or more per student at private institutions. It would impact but a nano-handful of institutions—around 50 out of thousands—and amounts to little more than a politicized, “Take That, Harvard!”

That said, the idea that higher ed is somehow teetering on the edge of financial destruction is ludicrous.

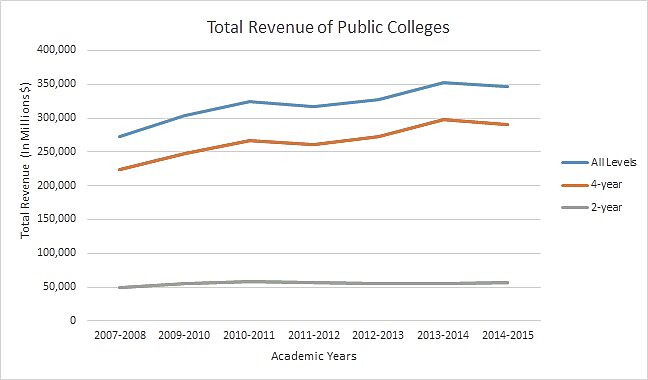

Consider revenues at public colleges since the onset of the Great Recession, during which we supposedly saw massive “disinvestment.” While it is true that total state and local appropriations dipped, total public college revenue rose markedly, from $273 billion in academic year 07–08, to $347 billion in 14–15, a 27 percent increase. Even on an inflation-adjusted, per-pupil basis revenue increased: From $31,561 per student in 07–08, to $32,887 in 14–15, a 4 percent rise. To put that in perspective, per-capita income in the United States is $28,930.

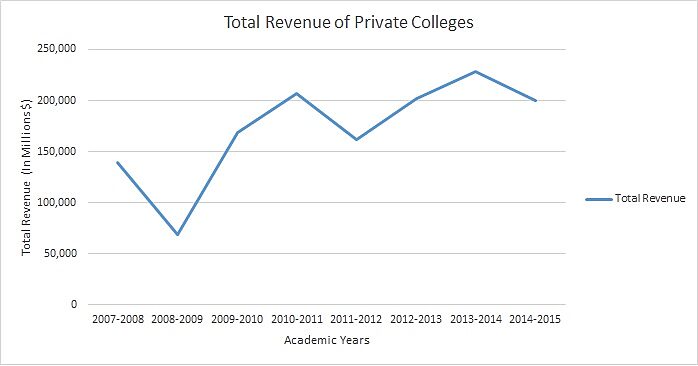

Federal data on private colleges is pretty volatile—it’s not clear why, for instance, between 07–08 and 08–09 total revenue dropped from $139 billion to $69 billion—but it, too, shows little sign of penury. Between 07–08 and 14–15 total revenue rose from $139 billion to $200 billion, a 44 percent increase, and inflation-adjusted per-pupil revenue went from $51,629 to $59,270, a 15 percent increase.

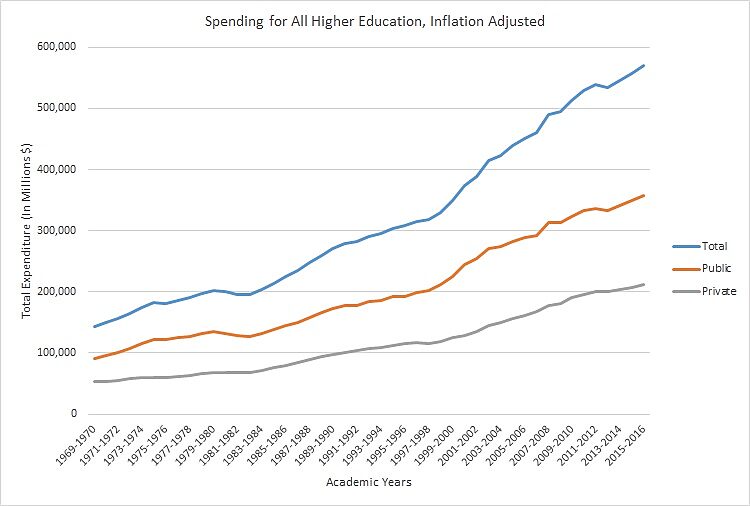

Using a longer timeframe, higher ed has clearly been raking it in for decades. Inflation-adjusted spending for all of higher education ballooned from $132.7 billion in 1969–70, to an estimated $548.0 billion in 2015–16, a 283 percent increase. Meanwhile, full-time equivalent enrollment rose from 6,333,357 to 15,076,819, just a 138 percent rise. This has, of course, been accompanied by skyrocketing prices. Such supposedly draconian measures as ending the student loan interest deduction—worth about $200 per year for the average claimant—or cutting private colleges off from tax-exempt bonds for construction is not going to alter that immensely.

Then there’s the key question: What have we gotten for all this money?

Answer: A glut of increasingly empty degrees coupled with greater school opulence.

Between 1992 and 2003—the only years the assessment was given—literacy for people with four-year and advanced degrees fell precipitously. In prose literacy, the share proficient dropped from 51 percent to 41 percent among advanced degree holders! Time spent studying plummeted from about 25 hours per week in 1961, to 20 hours in 1980, to 13 in 2003. Since 2000, earnings of people with BAs and above declined as the country experienced a major surplus of degree holders. Indeed, about a third of bachelors holders are in jobs that do not require the credential, and employers increasingly call for degrees in jobs that previously did not need them and don’t appear to have substantially changed. Finally, nearly 40 percent of students who enter college do not complete their programs within eight years, and many of those likely never will. Meanwhile, schools increasingly feature such luxuries as deluxe dorms and on-campus water parks.

In light of this, the trims that could come through the GOP tax plan hardly threaten to wreak higher education Ragnarok. Indeed, they may do for colleges and universities what the latest movie did for Thor: provide a much needed haircut.

Related Tags

The Fed’s Mispricing of Liquidity: Nothing New Under the Sun

I agree that the problem of mispriced Fed intraday credit was once serious, and that it has been “partly rectified.” The Fed made several attempts to improve its overdraft policies, and more recently, the vast increase in banks’ excess reserve holdings has made daylight overdrafts unnecessary.

Yet important questions remain concerning the extent to which the Fed continues to misprice its services, and to thereby violate the spirit and letter of the 1980 Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (DIDMCA, or MCA for short). These questions, along with Selgin’s concerns about the legality of the Fed’s above-market interest rate on bank reserves, suggest a need for heightened scrutiny of the Fed by Congress.

Here I survey the Fed’s post-MCA payments-pricing practices. I hope to show that, even though the mispricing of some of these services may have been “partly rectified,” there are still good reasons to doubt that the Fed has complied with the MCA’s provisions calling for it to fully recover “all direct and indirect costs” of the payment services it provides to banks.

Some History on the Fed-Subsidized Services

The Fed has published financial statements for its priced payment services ever since the MCA was passed. The statements report the Fed’s revenue, expenses, and cost recovery for those services under accounting standards set not by an independent standard setter, but by the Federal Reserve itself. Unsurprisingly, the Fed’s standards have allowed it to report that its revenue has fully recovered its costs over time, even when conventional standards would not have.

The Fed has thus been able, using its own financial statements, to defend itself when outside parties (and some rival, private suppliers of payment services) have accused it of subsidizing its payment services. For example, in a 1997 Congressional hearing, Alice Rivlin, then-vice chair of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, testified:

The MCA requires the Federal Reserve Banks to charge fees for their payment services, which must, over the long run, be set to recover all direct and indirect costs of providing the services. In addition, the MCA requires the Federal Reserve Banks to recover imputed costs, such as taxes and the cost of capital that would have been paid and imputed profits that would have been earned if the services were provided by a private firm.

…

Over the last ten years, the Federal Reserve has fully recovered the total costs of its priced services, including imputed costs as required by the Monetary Control Act. … Shortly after the MCA was enacted, the Board of Governors adopted pricing principles that are more stringent than the requirements of the MCA and that require the Federal Reserve Banks to recover priced service costs, not just in the aggregate, but for each major service category. Our check service, for example, has fully recovered its costs over the last ten years.[1]

In turn, in an appendix to the body of this testimony, Rivlin reiterated that

Taxpayers do not subsidize the cost of the Federal Reserve’s check transportation. It is understandable that whenever a public entity competes with the private sector in providing services, the issue of subsidies arises. The Monetary Control Act of 1980 (MCA) addressed that issue by requiring the Federal Reserve, over the long run, to set fees for its priced payment services to recover all direct and indirect costs of providing those services. [Emphasis original.]

Rivlin’s remarks had been anticipated by then-Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, who in his 1996 testimony to the Senate Banking Committee insisted that the Fed’s

priced services are subject to the inherent discipline of the marketplace as the Federal Reserve must control costs in order to meet the statutory directives for cost recovery in the Monetary Control Act. The risk-management decisions that we make concerning the way we provide payment services to depository institutions are tested directly in the marketplace. These services comprise more than one-third of the Federal Reserve banks’ total budget and the Monetary Control Act requires that, over the long run, we price these services to recover their costs, as well as costs that would be borne by private businesses, such as taxes and a return on equity. If we provide these services inefficiently, we price ourselves out of the market.

Over the past decade, our track record has been good. The Reserve Banks have recovered 101 percent of their total cost of providing priced services, including the targeted return on equity. I should also note that, by recovering not only our actual costs but also the imputed costs that a private firm would incur, the Federal Reserve´s priced services have consistently contributed to the amount we have transferred to the Treasury. During the past decade, priced services revenue has exceeded operating costs by almost $1 billion.[2]

Yet even with the help of their special accounting practices, Fed officials weren’t able to consistently maintain that its payments services weren’t subsidized. Just two months before Rivlin assured Congress that “Taxpayers do not subsidize the cost of the Federal Reserve’s check transportation,” Greenspan, in making a case for the Federal Reserve Board to serve as lead regulator for new financial holding companies, had been claiming just the opposite:

a number of observers have argued that there is no subsidy associated with the federal safety net for depository institutions — deposit insurance, and direct access to the Federal Reserve’s discount window and payment system guarantees. The Board strongly rejects this view.

…

While some benefits of the safety net are always available to banks, it is critical to understand that the value of the subsidy is smallest for very healthy banks during good economic times, and greatest at weak banks during a financial crisis. … What was it worth in the late 1980s and early 1990s for a bank with a troubled loan portfolio to have deposit liabilities guaranteed by the FDIC, to be assured that it could turn illiquid assets to liquid assets at once through the Federal Reserve discount window, and to tell its customers that payment transfers would be settled on a riskless Federal Reserve bank? [Emphasis added.][3]

Although Greenspan refers generally to subsidies offered by the Fed’s safety net, that net includes access to Fedwire as well as to the discount window.

In related 1997 testimony, Greenspan noted explicitly how the safety net (including Fedwire access) shifted risk to the government, and how, because that risk constituted a cost, the practice amounted to a subsidy provided to banks. “The use of sovereign credit in banking,” Greenspan said,

even its potential use — creates a moral hazard that distorts the incentives for banks: the banks determine the level of risk-taking and receive the gains therefrom, but do not bear the full costs of that risk. The remainder of the risk is transferred to the government. This then creates the necessity for the government to limit the degree of risk it absorbs by writing rules under which banks operate, and imposing on these entities supervision by its agents — the banking regulators — to assure adherence to these rules.[4]

Fedwire — the Fed’s wholesale funds transfer system — is one of the largest payment services the Fed provides. Prior to the recent crisis, banks paid one another more than $1 trillion every day using this service. The funds being transferred consisted of bank reserve account balances — balances on which the Federal Reserve now pays banks billions of dollars a year in interest.

Before the present “abundant reserves” era began, banks settled huge Fedwire payments volume on a relatively thin aggregate cushion of excess reserves, with the extension of intraday overdraft credit from the Fed a key enabler. Only a thin cushion sufficed because banks that ran short of reserves with which to meet either their settlement needs or their minimum legal requirements could, for a price, borrow both either from the Fed or, for overnight loans, from other banks, to avoid shortfalls. The Fed provided billions of dollars of intraday credit daily, the result of the fact that the Fed guaranteed Fedwire payments to receiving banks, notwithstanding that the sending bank might be short funds at the end of day — thereby exposing the Fed itself to credit risk.

The Fed’s fee schedules for Fedwire transfers have evolved over time, but they have consistently been based on a fee-per-transfer basis, with “volume” discounts available not for the dollar size of the transfer(s), but the number of transfers. In the scarce-reserves era, fees were generally a fraction of $1 per transfer, even for large dollar transfers utilizing large amounts of overdraft credit. For many years after 1980, the Fed didn’t even charge fees for intraday credit utilization, only beginning the practice in 1994 — with effective interest rates a small fraction of market interest rates. In turn, the Fed didn’t include daylight overdraft fees as revenue in its cost recovery calculation for pried services — despite acknowledging that the new payment system risk policy (in 1985) and overdraft fees (in 1994) were developed “[t]o reduce the risks that depository institutions present to the Federal Reserve through their use of daylight credit and to address the risks that payment systems, in general, present to the banking system and other sectors of the economy …”[5]

With the progress in the Fed’s payment system risk policies in the late 1980s and the development of overdraft fees in the mid-1990s, some Fed leaders claimed to have addressed the subsidy issue. However, they didn’t appear to have convinced the Fed Chairman, given that he was identifying Fedwire access as a subsidy in the late 1990s.

In light of the low fees being charged, even allowing for some improvements here and there, Fedwire sure looked like a subsidy. But for many years, the Fed was also asserting that Fedwire was not a subsidy, given that the Fed priced the services to fully recover “all direct and indirect costs.”

In 1999, Congress passed the Financial Services Modernization Act. This law established the Federal Reserve Board of Governors as the lead regulator and supervisor for financial holding companies. In making their case to Congress for the lead position, Fed leaders acknowledged, like Greenspan did in that 1997 testimony, that the Fed’s assumption of risk on Fedwire constituted a subsidy. The Fed was very concerned about the risk it was exposed to, the story went, and so the Fed had to be in the lead position as a regulator (and supervisor).

The Fed’s case for a lead supervisory role was (and is) ironic in another sense. Greenspan asserted that the shifting of risk to the government from safety net features like Fedwire drove the need for costly government supervision. So it could have been argued that the costs of this supervision were another element of the “direct and indirect costs” to be recovered by Fedwire pricing. But they were not.

Yes, Fedwire was subsidized. The Fed knew it, but didn’t account for it. And Congress stood idly by, as the Fed’s accountants and lawyers resorted to window-dressing to feign compliance with the law.

How About the New “Reserve-Abundant” Era?

In 2007 and early 2008, reserves at the Fed were running about $40–45 billion, with Fedwire accomplishing more than a $1 trillion a day in funds transfers. In those “old” days, some Fed officials actually argued that high Fedwire volume on a thin reserve base was evidence for how “efficient” the system was.

With the massive easing of monetary policy amidst the blooming financial crisis and arrival of IOR, reserves at the Fed mushroomed from $46 billion in August 2008 to more than $800 billion at the end of the year. And from there, reserves reached new heights, rising to nearly $3 trillion in 2015. Not surprisingly, as excess reserves ballooned, daylight overdrafts dropped to record low levels.

Let’s take a closer look at what was going on as the 2007–2009 financial crisis intensified. In the weeks leading up to mid-September 2008, peak daylight funds overdrafts were running at about $130 billion. From September 10 to September 24, however, peak overdrafts jumped to $200 billion, and higher still to $245 billion in the reserve period that ended October 8. The September 10 — October 8 period coincided with the onset of the burgeoning reserve balances — and rising fears (and failures) in the financial markets.

In other words, in the first weeks of sharply higher reserves, daylight overdrafts were actually still growing dramatically, with large financial firm failures exploding around the payment system minefield. It was only later, after the acceleration in QE, that daylight credit began falling.

In making their recent case for the efficiency of paying interest on reserves, Fed economists have praised the reduction in risk to the Fed, and the public, from the reduced utilization of intraday credit. For example, in a 2012 FRBNY article “How The High Level of Reserves Benefits the Payment System,”[6] Fed economists praised the new system: “we can document an important and overlooked benefit of the high level of reserves: a significantly earlier settlement of payments on Fedwire.” They continue, “[a]t the same time, the Fed has been extending less intraday credit, which reduces the public’s risk exposure.”

Can the Fed have it both ways? Was the Fed truly recovering “all direct and indirect costs” from 1980 until the financial crisis? Was Fedwire efficient back then, and even more efficient today?

Nothing New Under the Sun

A strong case can be made, and Selgin has made it, that in paying above-market interest on banks’ reserves, the Fed is not just subsidizing banks, but subsidizing them illegally.

But far from being an exceptional, new development, this practice is only the latest instance of the Fed’s longstanding practice of offering subsidized payments services, which it mainly did in the past by helping banks fund trillions of dollars in Fedwire payments with risky overdraft credit, without pricing that risk to fully recover the cost of providing Fedwire as required by law.

Daylight overdrafts have declined to next to nothing since 2008, while the problem of mispriced overdrafts, though seemingly in abeyance, has not actually been addressed. The Fed’s pricing of Fedwire and funds overdrafts continues to be at odds with the spirit, if not the letter, of the MCA’s cost recovery provisions. While daylight overdraft risk no longer poses the direct problem it used to, in “eliminating” it the Fed has created an even more serious problem (and indirect cost) of balance sheet risk for itself, and ultimately for taxpayers. In short, the Fed is now paying banks billions of dollars a year for the “privilege” of “reducing” the risk they pose to the Fed, and shifting it to the taxpaying public!

New Congressional hearings should explore these developments, with the aim of helping the Fed comply with the law, at long last.

_______________

[1] Alice M. Rivlin, “Role of the Federal Reserve in the Payment System,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Domestic and International Monetary Policy of the Committee on Banking and Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives. September 16, 1997.

[2] Alan Greenspan, “Recent reports on Federal Reserve operations,” testimony before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate. July 26, 1996.

[3] Alan Greenspan, “The Financial Services Competition Act of 1997,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Finance and Hazardous Materials of the Committee on Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives. July 17, 1997.

[4] Alan Greenspan, “Modernization of the Financial System,” testimony before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit of the Committee on Banking and Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives. February 13, 1997.

[5] Stacy Panigay Coleman, “The Evolution of the Federal Reserve’s Intraday Credit Policies,” Federal Reserve Board of Governors Bulletin (February 2002)

[6] Morton Bech, Antoine Martin, and Jamie McAndrews, “How the High Level of Reserves Benefits the Payment System,” Liberty Street Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. February 12, 2012.

Disclaimer

This post was originally published at Alt‑M.org. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Cato Institute. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign, defame, or insult any group, club, organization, company, or individual.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The Cato Institute makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. Cato Institute, as a publisher of this article, shall not be liable for any misrepresentations, errors or omissions in this content nor for the unavailability of this information. By reading this article and/or using the content, you agree that Cato Institute shall not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this content.

Related Tags

Economists Oppose a Strict Balanced Budget Rule. Could the US Adopt a Sophisticated One?

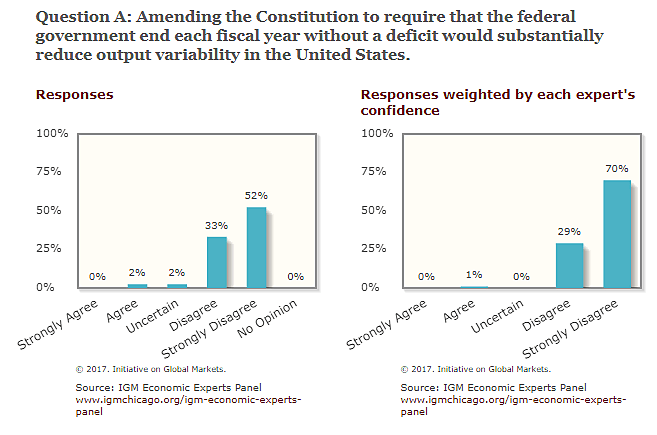

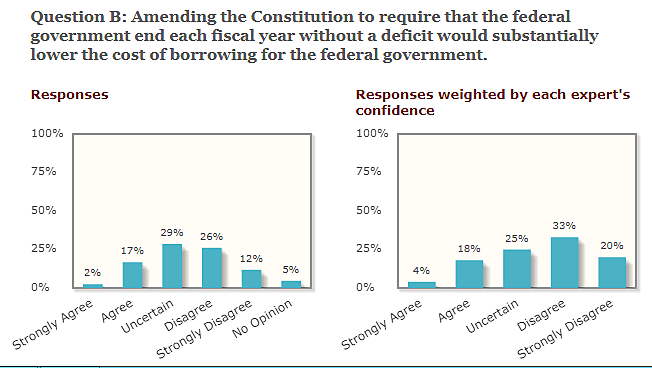

The IGM Economic Experts Panel overwhelmingly opposes a constitutional strict balanced budget amendment.

Weighted by the confidence of their answers, 99 percent of responders disagree or strongly disagree that a requirement the federal government balance the books would reduce output volatility; whilst 53 percent disagree with the view that it would lower federal borrowing costs.

This is timely. House Speaker Paul Ryan (R‑WI) has tasked Rep. Doug Collins (R‑Ga.) as part of a 22-person strong task force to consider alternative fiscal rules to the debt ceiling to help constrain the growth of US federal government debt. The task force offers its recommendations in December. Whilst the task force’s remit does not extend to constitutional change, the cost and benefits of different fiscal rules are bound to shape their thinking.

Why do economists demur over an ex-post balanced budget requirement that forces balance every year? Two main answers appear. First, there’s the Keynesian argument that fiscal policy can and should be used to smooth the business cycle, especially via discretionary deficit-spending during recessions. In this view, a balanced budget amendment can exacerbate output volatility by outlawing potentially helpful fiscal support and enforcing cuts when the economy is in a cyclical downturn.

Second, there’s Robert Barro’s “tax smoothing” argument, which says a government can minimize the distortionary impact of taxation by keeping tax rates relatively smooth or constant and allowing government debt to be a shock-absorber to unexpected shocks.

I’d add two more. The risk of major within-year changes to the funding programs greatly increase uncertainty for many individuals and households and makes budgeting very difficult. And a balanced budget amendment could incentivize governments to run up high spending and new programs during boom periods when there’s a “windfall” in terms of tax revenues. These could then prove “sticky” and difficult politically to get rid of, running the risk of even larger government overall with a higher tax burden in the long-term.

Economists have long recognized these problems, which is why other countries that have adopted forms of “balanced budget rules” have not adopted strict ex-post rules that do not permit any deficits.

Most modern rules in countries deemed to be successful instead seek to cap government expenditures in any given year based on trends in revenues or some estimate of “potential” GDP, meaning that revenues and hence spending caps are largely “cyclically adjusted.”

This “structural balance” means, in theory, surpluses during boom periods and deficits during periods where growth is weaker-than-trend or below potential. The result, if trends remain constant or potential GDP is estimated correctly, is the debt-to-GDP path falls overall during the business cycle, with nominal GDP rising and the budget balanced over the cycle.

The details, of course, are very different depending on the country. Switzerland stabilizes spending around a revenue trend with its so-called “debt brake,” with any deviations from forecasts within-year made up over longer periods. Their rule is constitutionally-grounded.

Chile targets a structural balance through spending caps based upon estimates of potential GDP and the price of copper calculated by independent committees, but with no consequences if outturns differ from forecasts.

Sweden has a rule requiring a budget surplus equal to 1 percent of GDP on average over the business cycle, but with more freedom for governments to run structural deficits (provided they make up for them later).

All of these are more complex than a simple balanced budget requirement. And they come with risks. In particular, most of them are vulnerable should trends in economic growth change substantially, or the economy’s output gap gets calculated incorrectly—highly likely, given estimating it correctly requires measuring accurately current GDP, potential GDP, and how spending and revenues would react to moving towards potential GDP. But overall, they are more economically sensible than a rigid year-on-year balanced budget rule.”

I’ll blog in the coming weeks about other countries’ specific experiences with these types of fiscal rules. But one conclusion that stands out from the vast literature is that rules require buy-in both from the political class and the broader public to be effective. It is no coincidence, for example, that Sweden introduced its rule after a budget crisis in the 1990s, and Switzerland’s constitutional rule was delivered after obtaining 85% support from voters in a 2001 referendum. Without a broad consensus behind a rule, politicians seek to circumvent them with clever accounting, off-balance-sheet wheezes, optimistic forecasts and, ultimately, abandoning the rules when they start to bind.

Asking whether particular fiscal rules could be applied to the US federal government, in a technocratic sense, puts the cart before the horse. Yes, rules can bring focus on an issue and provide a framework for budgeting. But the elephant in the room is the question: does the US have the political will to move towards fiscal discipline? Bill White’s “American’s Fiscal Constitution” shows that in the past such a consensus for fiscal probity existed. But given the federal budget is now used for so many purposes, and with the political parties so divided on the optimal size of the state, could such a consensus exist again?