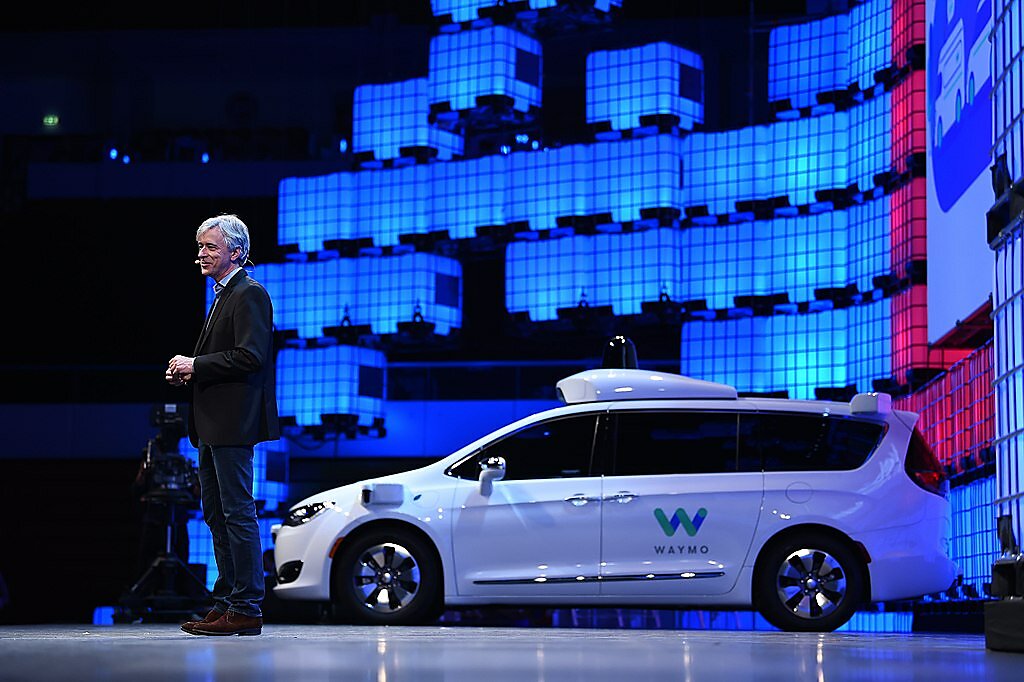

A fleet of driverless cars designed by Waymo, a project of Google’s parent company, Alphabet, is on the roads of Phoenix, Arizona. Last week, Waymo CEO John Krafcik announced that in the coming months the driverless cars will be part of the world’s first autonomous ride-hailing service. The recent news is a milestone in driverless car technology history, and it’s no exaggeration to claim that the technology behind these new cars has the potential to save hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of lives in the coming decades. Sadly, drones, another life-saving technology, have had a tougher time getting off the ground.

Waymo’s cars are not suddenly arriving on the scene. Google has been working on getting a driverless car on the road since 2009, and Waymo has been offering some lucky passengers in the Phoenix area rides since April. However, these cars had a driver at the wheel, just in case. The fleet now driving in Phoenix does not include safety drivers.

This may prompt unease among some Phoenix residents. A clear majority of Americans are uncomfortable about getting into driverless cars. Yet human drivers are deadly. More than 90 percent of car crashes can be attributed to human error, and motor vehicle accidents killed an estimated 40,200 people on American roads last year.

Fortunately, the life-saving potential of driverless cars seems to have been a persuasive selling point to lawmakers and regulators. This is in part because of their massive unrealized benefits, but also because auto-safety regulators tend to allow car manufacturers to get their product on the market after certifying that they’re in compliance with safety standards, relying on recalls if and when safety standards are violated, as Ars Technica technology reporter Timothy Lee explained:

Another important factor is that auto-safety regulators have a tradition of being relatively deferential to car companies. Agencies like the Food and Drug Administration require companies to seek pre-market approval for their products. By contrast, the approach of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is to set out general guidelines requiring features like airbags and antilock brakes and then ask automakers to self-certify their compliance. NHTSA then relies on after-market recalls to deal with vehicles that turn out to be defective.

This approach creates a somewhat greater risk of defective products reaching the marketplace. But it also enables automakers to get potentially lifesaving innovations into the marketplace more quickly. And carmakers are large, bureaucratic organizations that have strong incentives to color inside the lines, so there’s not much reason to worry about small, fly-by-night manufacturers sneaking defective products into the marketplace.

We shouldn’t forget that the technology will improve lives as well as save them. For the elderly and the disabled, driverless technology offers the chance to vastly improve mobility. In fact, last year Google’s driverless car drove a blind man, Steve Mahan, in Austin. According to Mahan, “This is a hope of independence. These cars will change the life prospects of people such as myself. I want very much to become a member of the driving public again.” Parents with children busy with after-school activities will also undoubtedly benefit from the kind of driverless ride-hailing service Waymo plans to offer.

Driverless cars are not the only emerging technology that could save and improve lives. Sadly, however, these other products are governed by a tougher regulatory framework than that overseeing Waymo’s cars.

Amazon’s experience with drones has been off to a difficult regulatory start. The Internet giant, which is interested in developing delivery drones, went to England to conduct its first drone-delivery test last year. This was despite the fact that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced drone delivery plans as far back as 2013 and applied for permission from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to test drones in 2014. That same year, the AP noted that other countries were outpacing the United States when it came to drone regulation:

The Federal Aviation Administration bars all commercial use of drones except for 13 companies that have been granted permits for limited operations. Permits for four of those companies were announced Wednesday, an hour before a hearing of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s aviation subcommittee. The four companies plan to use drones for aerial surveillance, construction site monitoring and oil rig flare stack inspections. The agency has received 167 requests for exemptions from commercial operators.

Several European countries have granted commercial permits to more than a 1,000 drone operators for safety inspections of infrastructure, such as railroad tracks, or to support commercial agriculture, Gerald Dillingham of the Government Accountability Office testified. Australia has issued more than 180 permits to businesses engaged in aerial surveying, photography and other work, but limits the permits to drones weighing less than 5 pounds. And small, unmanned helicopters have been used to monitor and spray crops in Japan for more than a decade.

By the time the FAA approved Amazon’s drone it was already obsolete and out of date, with Amazon testing a more advanced drone. Amazon’s vice president of global public policy told the Senate Subcommittee on Aviation Operations, Safety, and Security in 2015, “Nowhere outside of the United States have we been required to wait more than one or two months to begin testing.”

Like driverless cars, drones are potentially life saving, with firefighters, emergency medical technicians, and building inspectors—among many others—standing to benefit from their use. Zipline, a California-based company that makes medical delivery drones, was founded in 2014. And yet, Zipline co-founder and chief executive Keller Rinaudo noted in August that, despite being based in California, Zipline had not flown any flights in the United States.

By September of this year, Zipline had flown “1,400 flights and delivered 2,600 units of blood” in rain and high winds in Rwanda.

Amazon Prime Air, by comparison, is much more restricted:

We are currently permitted to operate during daylight hours when there are low winds and good visibility, but not in rain, snow or icy conditions. Once we’ve gathered data to improve the safety and reliability of our systems and operations, we will expand the envelope.

Fortunately, the Trump administration has taken steps to allow for a more innovative drone environment, last month launching a drone program that will allow local governments and companies to experiment with drones in a more relaxed regulatory environment.

Regulatory agencies should take an approach that allows companies to ask for forgiveness rather than permission, an approach laid out by Mercatus’ Adam Thierer in his book Permissionless Innovation. When it comes to the FAA and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for instance, the approach is the reverse. Almost four years ago, the FDA shut down the personal genome testing company 23andMe after it marketed its saliva collection kit “without marketing clearance or approval.” In its letter to 23andMe, the FDA did not cite any 23andMe customers who had complained about 23andMe’s product.

It would be naive to think that there won’t be bumps in the road as more driverless cars take to the streets. For example, driverless cars could prompt regulatory fights between states and the federal government, although House and Senate driverless car legislation contain identical provisions that seek to address preemption concerns. There are also issues related to cybersecurity and insurance, but we shouldn’t forget that profit-maximizing firms have incentives to not kill or injure their customers.

Regulatory reform concerning new and emerging technology is long overdue. 3D printing, the “Internet of Things,” drones, driverless cars, and robotics, are only some of the exciting new technologies and fields that hold the potential to enrich and save lives. These benefits will be sooner realized if regulators set innovators free. The ubiquity of driverless cars won’t make the world perfect, but it will make the world better.