It’s Car Free Day in Washington, and the traffic on I‑66 was the worst in memory.

Update: Link fixed.

It’s Car Free Day in Washington, and the traffic on I‑66 was the worst in memory.

Update: Link fixed.

Professor William Easterly, the economic development expert from New York University, has written an excellent comment for the Financial Times online. He writes, “The Millennium Development Goals [summit that wraps up in NY today] tragically misused the world’s goodwill to support failed official aid approaches to global poverty and gave virtually no support to proven approaches. … But current experience and history both speak loudly that the only real engine of growth out of poverty is private business, and there is no evidence that aid fuels such growth.”

At the Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity, we have continuously emphasized the power of trade to help the poor escape poverty. Unfortunately, politicians in rich countries find it easier to waste billions of taxpayers’ dollars in the form of foreign aid than to take on special interests that thrive on trade protectionism; hence European and American agricultural tariffs and subsidies.

However, the impact of rich countries’ protectionism should not be exaggerated. African countries are typically more protectionist than rich countries. In fact, they are more protectionist against one another than against rich countries. The sad truth is that poor countries are perfectly able to shoot themselves in the foot by following growth-killing economic policies – irrespective of what the rich countries do.

Foreign aid, incidentally, has been ineffective at promoting liberalization.

John Podesta of the Center for American Progress had a column in Politico yesterday asserting that “closing the budget gap entirely on the spending side would require draconian programmatic cuts.” He went on to complain that there are some people who “refuse to look at the revenue side of the ledger – while insisting that we dig the hole $830 billion deeper over the next decade by extending the Bush tax cuts.”

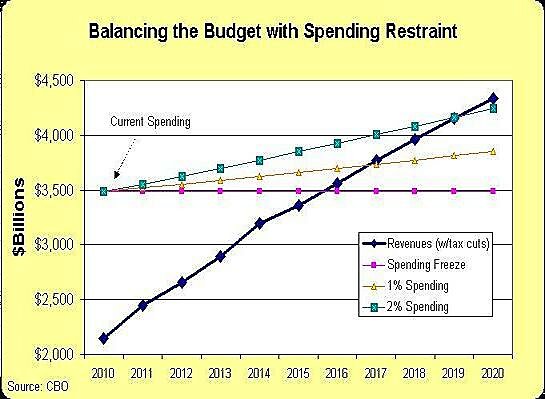

Not surprisingly, Mr. Podesta is totally wrong. It’s actually not that challenging to balance the budget. And it doesn’t even require any spending cuts, though it would be a very good idea to dramatically downsize the federal government. Here’s a chart showing this year’s spending and revenue totals. It then shows the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of how much revenues will grow, assuming all the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are made permanent and assuming that the alternative minimum tax is adjusted for inflation. As you can see, balancing the budget is a simple matter of limiting the annual growth of federal spending.

So how is it that Mr. Podesta can spout sky-is-falling rhetoric about “draconian” cuts when all that’s needed is fiscal restraint? The answer is that politicians in Washington have concocted a self-serving budget process that automatically assumes that all previously-planned spending increases should occur. So if the politicians put us on a path to make government 8 percent bigger next year and there is a proposal to instead limit spending growth to 3 percent, that 3 percent increase gets portrayed as a 5 percent cut.

This is a great scam, at least for the political class. They get to buy more votes by boosting the burden of government spending, but they get to tell voters that they’re being fiscally responsible. And they get to claim that they have no choice but to raise taxes because there’s no other way to balance the budget. In the real world, though, this translates into bigger government and puts us on a path to a Greek-style fiscal nightmare.

The goal of fiscal policy should be smaller government, not fiscal balance. Deficits are just a symptom of a government that is too large, as I have explained elsewhere. But the good news is that spending discipline is the right answer, regardless of the objective. I explained this in more detail for a piece in today’s Philadelphia Inquirer. Here’s an excerpt.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government this year is spending almost $3.5 trillion. Tax receipts are estimated to be less than $2.2 trillion, which means a projected deficit of about $1.35 trillion. So can we balance the budget when there is that much red ink? And is it possible to eliminate deficits while also extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts? The answer is yes. …It’s a simple matter of mathematics. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that tax revenue will grow by an average of 7.3 percent annually over the next 10 years. Reducing the budget deficit is easy — so long as politicians increase overall spending by less than that amount. And with inflation projected to be about 2 percent over the same period, this is an ideal environment for some long-overdue fiscal discipline. If spending is simply capped at the current level with a hard freeze, the budget is balanced by 2016. If we limit spending growth to 1 percent each year, the budget is balanced in 2017. And if we allow 2 percent annual spending growth — letting the budget keep pace with inflation, the budget balances in 2020. …Interest groups that are used to big budget increases will be upset if spending growth is limited to 1 or 2 percent each year. It means entitlements will need to be reformed. It means we might need to get rid of programs and departments that are not legitimate functions of the federal government. You better believe that these changes will cause a lot of squealing by lobbyists and other insiders. But that complaining will be a sign that fiscal policy is finally heading in the right direction. The key thing to understand is that there is no need for tax increases. Politicians might not balance the budget if we say no to all tax increases. But the experience in Europe shows that oppressive tax burdens are not a recipe for fiscal balance either. Milton Friedman was correct many years ago when he warned that, “In the long run government will spend whatever the tax system will raise, plus as much more as it can get away with.”

The New York Times reports that the book, Obama’s Wars, by longtime Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward that is scheduled for publication next week, depicts an administration completely at odds over the war in Afghanistan.

According to Woodward, the president concluded from the start that “I have two years with the public on this.” He implored his advisers at one meeting, “I want an exit strategy,” and he set a withdrawal timetable because, “I can’t lose the whole Democratic Party.”

It’s unfortunate that the policy debate over Afghanistan will be further spun into a left-vs.-right issue. After all, there are growing, if nascent, signs that some on the political right have reservations about our continued military involvement in Afghanistan. Earlier this year, Congressman Tim Johnson (R‑Ill.), who earned an 80 percent favorable rating from the American Conservative Union, was a GOP co-sponsor to Rep. Dennis Kucinich’s (D‑Ohio) resolution to force the removal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. In March, Congressman John Duncan (R‑Tenn.) came to the Cato Institute and explained why “there is nothing conservative about the war in Afghanistan.”

And as Cato founder Ed Crane wrote last year in the pages of the LA Times:

Republicans should take this opportunity to return to their traditional non-interventionist roots, and throw their neoconservative wing under the bus and forcefully oppose the war in Afghanistan. The Republicans have a chance at this moment to reclaim the mantle of the party of non-intervention — in your health care, in your wallet, in your lifestyle, and in the affairs of other nations.

I am not a conservative, and neither are many of my Cato colleagues. But these comments are intended to highlight that leaving Afghanistan is far beyond Left vs. Right. In fact, many conservatives used to deride nation-building as a utopian venture that had little to do with the nation’s real interests. In the case of Afghanistan, troops are being deployed to prop up a regime Washington doesn’t trust, for goals our president can’t define. There is a principled case to be made that a prolonged nation-building occupation is weakening our country militarily and economically. It’s a question of scarce resources and limiting the power of government. The immense price tag for war in Afghanistan can no longer be swept under the carpet or dismissed as an issue owned by peaceniks and pacifists, much less “the Democratic Party.”

It must be the week for libertarian podcasts. Right after my UnitedLiberty interview on the 2010 elections, NPR’s Planet Money offers this podcast with Mark Calabria and me on libertarianism. (By the way, “under libertarianism, you would be better-looking, you would be taller” is a joke.…)

When I did talk shows after the publication of Libertarianism: A Primer, I was always asked, “What is libertarianism?” I said then, “Libertarianism is the idea that adult individuals have the right and the responsibility to make the important decisions about their lives. And of course today government claims the power to make many of those decisions for us, from where to send our kids to school to what we can smoke to how we must save for retirement.”

Here’s another way to put it, which I believe I first saw in a high-school libertarian newsletter from Minnesota: Smokey the Bear’s rules for fire safety also apply to government: Keep it small, keep it in a confined area, and keep an eye on it.

For more on libertarianism, check out my entry at the Encyclopedia Britannica. For longer treatments, see Libertarianism: A Primer and The Libertarian Reader. For deeper thoughts, take a look at Realizing Freedom: Libertarian Theory, History, and Practice. Find an 80-minute interview on libertarianism here and a short talk here.

An essay from economist Arnold Kling in the latest Cato Policy Report discusses what Kling calls the “knowledge-discrepancy problem.” This occurs when knowledge is dispersed but power is concentrated, and it is particularly acute in government.

In short, it’s impossible for government “experts” to aggregate the vast amount of knowledge that is dispersed throughout the economy in order to optimally direct economic activity. And as Kling notes, concentrating power over the economy in the hands of experts leads to ever more undesirable government interventions:

As we have seen, the expectations placed on government experts tend to be unrealistically high. This selects for experts with unusual hubris. The authority of the state gives government experts a dangerous level of power. And the absence of market discipline gives any errors that these experts make an opportunity to accumulate and compound almost without limit. In recent decades, this knowledge-power discrepancy has gotten worse. Knowledge has grown more dispersed, while government power has become more concentrated.

The failure of the administration’s stimulus plan illustrates the problem with empowering government experts to “fix” our incredibly diverse $14 trillion economy.

A Wall Street Journal article on the inability of government bureaucracies to utilize stimulus funds demonstrates the inherent inefficiency of government planning. For example, the stimulus provided $5 billion to the states for weatherization projects. But when a local official in Detroit began soliciting applications to weatherize houses, she ran into a buzz saw of federal and state red tape:

But on the same day in March 2009 that Shenetta Coleman picked up applications from 46 companies, she received an email from the Michigan Department of Human Services telling her she couldn’t award work to anyone.

The problem: Ms. Coleman hadn’t met requirements for her advertisement. Those included specifying the precise wages that contractors would have to pay, and posting the advertisement on a specific website. There were other rules—federal, state and local—for grant and contract-award processes, historic preservation and labor standards.

The bureaucratic obstacles Ms. Coleman hit took more than a year to clear. Some were mandated by the stimulus bill, the same legislation that was supposed to rapidly create jobs. For example, there is a union-backed provision that requires that weatherization workers receive the prevailing wages in the area.

The stimulus is also distorting employment by incentivizing workers to obtain job-skills on the basis of government planning. The WSJ article cites the example of an unemployed worker who enrolled in a weatherization training class when she learned that Detroit would be receiving $30 million in weatherization funds:

She studied energy-saving principles, practiced drilling holes into walls and blowing in insulation, and learned how to install windows. She graduated in March, at the top of her class. For the next four months, she couldn’t find work. “I was hanging on by a thread,” said Ms. Wallisch. In July, she was hired for energy-conservation work funded not by the stimulus plan, but by Michigan’s utility companies.

The recession, and consequent rise in unemployment, led to demands for the government to “create jobs.” However, merely throwing taxpayer money at government job-creating schemes, which was the solution the government’s “experts” came up with, was never a viable solution. The experts simply do not have the requisite knowledge to match millions of workers possessing diverse job-skills with the diverse needs of millions of employers.

From Kling:

What the issue of job creation illustrates is the problem of treating government experts as responsible for a problem that cannot be solved by a single person or a single organization.

Economic activity consists of patterns of trade and specialization. The creation of these patterns is a process too complex and subtle for government experts to be able to manage.

The issue also illustrates the way hubris drives out true expertise. The vast majority of economists would say that we have very little idea how much employment is created by additional government spending. However, the economists who receive the most media attention and who obtain the most powerful positions in Washington are those who claim to have the most precise knowledge of “multipliers.”

As I have previously discussed, the average citizen has become conditioned to reflexively turn to the government to in times of crisis. Government officials are only too happy to oblige as they are naturally inclined to operate on a short-term horizon (i.e., the next election). Fortunately, more and more Americans appear to be realizing that the government and its experts are the problem rather than the solution.

Our tax system in America is an absurd nightmare, but at least we have some ability to monitor what is happening. We can’t get too aggressive (nobody wants the ogres at the IRS breathing down their necks), but at least we can adjust our withholding levels and control what gets put on our annual tax returns. The serfs in the United Kingdom are in much worse shape. To a large degree, the tax authority (Inland Revenue) decides everyone’s tax liability, and taxpayers have no role other than to meekly acquiesce. But now the statists over in London have decided to go one step farther and have proposed to require employers to send all paychecks directly to the government. The politicians and bureaucrats that comprise the ruling class then would decide how much to pass along to the people actually earning the money. Here’s a CNBC report on the issue.

The UK’s tax collection agency is putting forth a proposal that all employers send employee paychecks to the government, after which the government would deduct what it deems as the appropriate tax and pay the employees by bank transfer. The proposal by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) stresses the need for employers to provide real-time information to the government so that it can monitor all payments and make a better assessment of whether the correct tax is being paid. …George Bull, head of Tax at Baker Tilly, told CNBC.com. “If HMRC has direct access to employees’ bank accounts and makes a mistake, people are going to feel very exposed and vulnerable,” Bull said. And the chance of widespread mistakes could be high, according to Bull. HMRC does not have a good track record of handling large computer systems and has suffered high-profile errors with data, he said. …the cost of implementing the new system would be “phenomenal,” Bull pointed out. …The Institute of Directors (IoD), a UK organization created to promote the business agenda of directors and entreprenuers, said in a press release it had major concerns about the proposal to allow employees’ pay to be paid directly to HMRC.

This is withholding on steroids. Politicians love pay-as-you-earn (as it’s called on the other side of the ocean), largely because it disguises the burden of government. Many workers never realize how much of their paychecks are confiscated by politicians. Indeed, they probably think greedy companies are to blame when higher tax burdens result in less take-home pay. This new system could have an even more corrosive effect. It presumably would become more difficult for taxpayers to know how much government is costing them, and some people might even begin to think that their pay is the result of political kindness. After all, zoo animals often feel gratitude to the keepers that feed (and enslave) them.