John Podesta of the Center for American Progress had a column in Politico yesterday asserting that “closing the budget gap entirely on the spending side would require draconian programmatic cuts.” He went on to complain that there are some people who “refuse to look at the revenue side of the ledger – while insisting that we dig the hole $830 billion deeper over the next decade by extending the Bush tax cuts.”

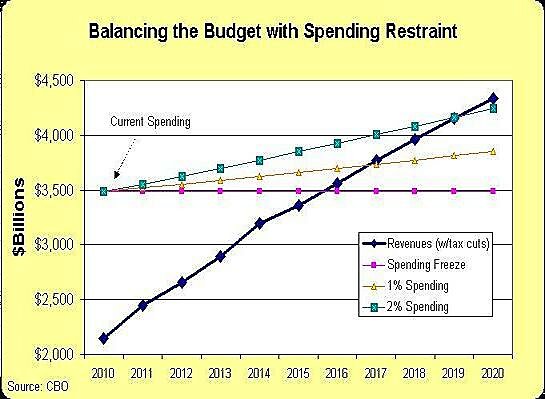

Not surprisingly, Mr. Podesta is totally wrong. It’s actually not that challenging to balance the budget. And it doesn’t even require any spending cuts, though it would be a very good idea to dramatically downsize the federal government. Here’s a chart showing this year’s spending and revenue totals. It then shows the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of how much revenues will grow, assuming all the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are made permanent and assuming that the alternative minimum tax is adjusted for inflation. As you can see, balancing the budget is a simple matter of limiting the annual growth of federal spending.

So how is it that Mr. Podesta can spout sky-is-falling rhetoric about “draconian” cuts when all that’s needed is fiscal restraint? The answer is that politicians in Washington have concocted a self-serving budget process that automatically assumes that all previously-planned spending increases should occur. So if the politicians put us on a path to make government 8 percent bigger next year and there is a proposal to instead limit spending growth to 3 percent, that 3 percent increase gets portrayed as a 5 percent cut.

This is a great scam, at least for the political class. They get to buy more votes by boosting the burden of government spending, but they get to tell voters that they’re being fiscally responsible. And they get to claim that they have no choice but to raise taxes because there’s no other way to balance the budget. In the real world, though, this translates into bigger government and puts us on a path to a Greek-style fiscal nightmare.

The goal of fiscal policy should be smaller government, not fiscal balance. Deficits are just a symptom of a government that is too large, as I have explained elsewhere. But the good news is that spending discipline is the right answer, regardless of the objective. I explained this in more detail for a piece in today’s Philadelphia Inquirer. Here’s an excerpt.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government this year is spending almost $3.5 trillion. Tax receipts are estimated to be less than $2.2 trillion, which means a projected deficit of about $1.35 trillion. So can we balance the budget when there is that much red ink? And is it possible to eliminate deficits while also extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts? The answer is yes. …It’s a simple matter of mathematics. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that tax revenue will grow by an average of 7.3 percent annually over the next 10 years. Reducing the budget deficit is easy — so long as politicians increase overall spending by less than that amount. And with inflation projected to be about 2 percent over the same period, this is an ideal environment for some long-overdue fiscal discipline. If spending is simply capped at the current level with a hard freeze, the budget is balanced by 2016. If we limit spending growth to 1 percent each year, the budget is balanced in 2017. And if we allow 2 percent annual spending growth — letting the budget keep pace with inflation, the budget balances in 2020. …Interest groups that are used to big budget increases will be upset if spending growth is limited to 1 or 2 percent each year. It means entitlements will need to be reformed. It means we might need to get rid of programs and departments that are not legitimate functions of the federal government. You better believe that these changes will cause a lot of squealing by lobbyists and other insiders. But that complaining will be a sign that fiscal policy is finally heading in the right direction. The key thing to understand is that there is no need for tax increases. Politicians might not balance the budget if we say no to all tax increases. But the experience in Europe shows that oppressive tax burdens are not a recipe for fiscal balance either. Milton Friedman was correct many years ago when he warned that, “In the long run government will spend whatever the tax system will raise, plus as much more as it can get away with.”