Harold Meyerson, with whom I’ve rarely found occasion to agree, makes one point in today’s column (“Go Slower on Free Trade”) that didn’t cause my eyes to roll: that the Obama administration has been relentlessly secretive about the goings-on in the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade negotiations.

I cannot corroborate Meyerson’s claim that the administration has granted access to the negotiators and the negotiating text to “roughly 600 trade ‘advisers’ from big businesses,” but has excluded everyone else, including Congress. It may be true, but then again… Certainly, Congress (by which I mean Congress, and not just a few Senate Democrats) is very much in the dark about the details of these negotiations, and that presents an enormous logistical problem.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution vests power in the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations,” which covers trade agreements. Traditionally, Congress has temporarily extended that authority to the executive branch, given the impracticability of having 535 trade representatives with 535 different agendas negotiating with foreign governments. That temporary grant of “fast track” or “trade promotion” authority is not a blank check. It comes with a list of congressional demands – items that can, cannot, must, and must not be included in the agreement. It is like doing the legislative process in reverse in the sense that amendments are articulated as conditions BEFORE the agreement is reached. Ideally, those congressional demands would be formalized before the negotiations BEGIN so that there are no false starts.

But with the administration still aiming to conclude negotiations in October, no fast track legislation in sight, and anti-trade legislation metastasizing in a Congress that has largely been excluded from shaping the deal’s terms, there are long battles ahead. Meyerson’s counsel that we “go slower on free trade” is probably already a done deal.

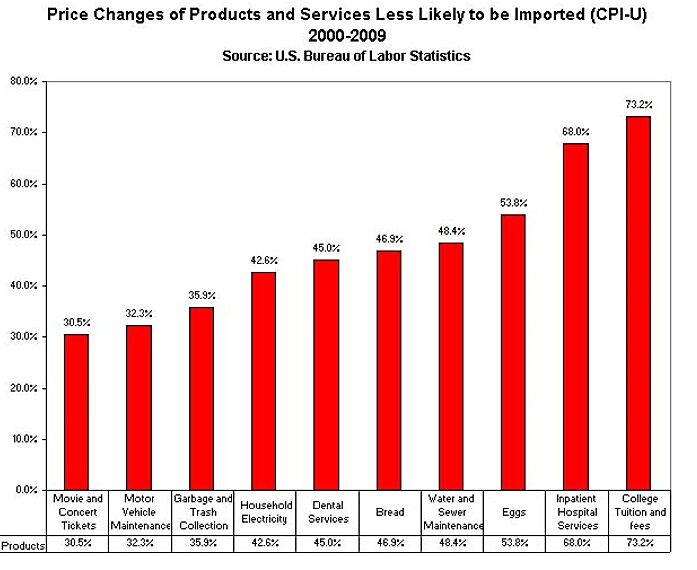

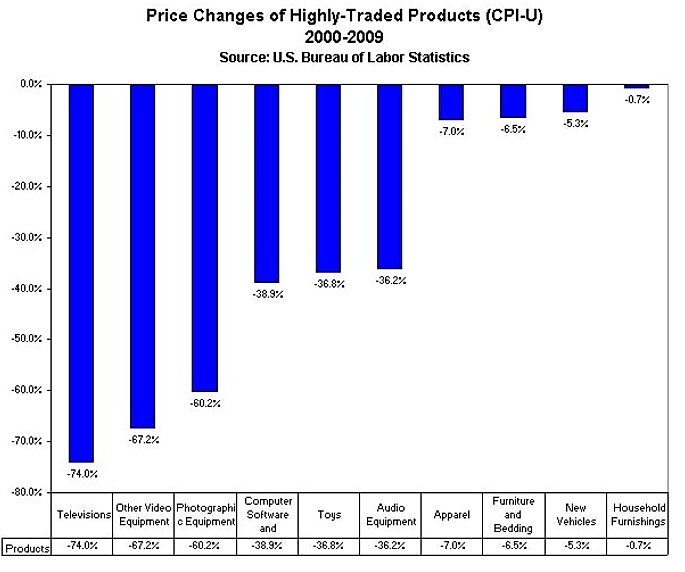

As to the rest of Meyerson’s claims that trade is a boon for big business, which comes at the expense of workers and consumers, we have harvested countless forests here at Cato explaining why that is just false. The most persistent U.S. trade barriers are imposed on food (tariffs and tariff-rate quotas), clothing (tariffs), and shelter (trade remedies restrictions on lumber, steel, cement, paint, nails, appliances, flooring, furniture, etc.), making them the most regressive taxes in the U.S. system. Lower-income Americans (those for whom Meyerson claims to speak) devote larger shares of their budgets to these basic necessities than do white-collar fat cats.

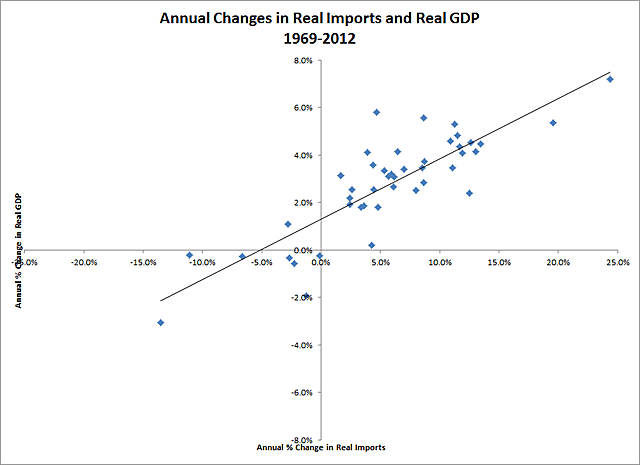

I’ll leave you with these three charts, which demonstrate positive relationships between import and jobs, price decreases over time for heavily traded items, and price increases over time for less frequently traded services, all exposing the errors of Meyerson’s claims.