Of many dubious claims that recent Federal Reserve Board nominee Stephen Moore made in a Wall Street Journal op-ed he published a couple weeks ago, perhaps the most startling was his claim that “to break the crippling inflation of the 1970s,” former Fed chair Paul Volcker linked Fed monetary policy to real-time changes in commodity prices. When commodity prices rose, Mr. Volcker saw inflation coming and increased interest rates. When commodities fell in price, he lowered rates.

Of course it’s true that, in the early 1980s (not the late 1970s), Paul Volcker’s Fed finally reigned-in the U.S. inflation rate. It’s also true that the Dodd-Frank Act’s section 619 implements a “Volcker Rule” barring banks from using customer deposits to engage in various kinds of proprietary trading. But I dare say it will be news to most people, as it was to me, that Volcker’s Fed tamed inflation by following another “Volcker Rule” that strictly geared its policy rate to the observed level of the prices of various commodities.

Instead, the story most of us have heard is that Volcker, inspired by monetarist writings, embraced a version of monetary targeting. As Ben Bernanke tells it, in October 1979

Volcker adopted an operating procedure based on the management of non-borrowed reserves. The intent was to focus policy on controlling the growth of M1 and M2 and thereby to reduce inflation, which had been running at double-digit rates. As you know, the disinflation effort was successful and ushered in the low-inflation regime that the United States has enjoyed since. However, the Federal Reserve discontinued the procedure based on non-borrowed reserves in 1982.

Whether targeting non-borrowed reserves was equivalent to targeting any (let alone more than one) monetary aggregate, and whether Volcker really cared whether it served that purpose, may well be doubted. Still, it is a long way from targeting any sort of index of commodity prices.

So, just where did Moore get the idea that Volcker had embraced commodity-price targeting? A little sniffing around produced the answer: from his long-time friend, fellow Trump-booster, and frequent coauthor, Arthur Laffer.

Laffer’s account of how Volcker embraced commodity-price targeting occurs on pp. 229–30 of Return to Prosperity (2010), one of the pair’s co-authored books:

In the early 1980s under gifted Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker (1979–87), the United States once again returned to a price rule, only this time the dollar was not pegged to gold. Following a meeting I had with Chairman Volcker in 1982, I cowrote an article for the editorial page of the Wall Street Journal. In this article Charles Kadlec and I outlined in detail Chairman Volcker’s vision of a price rule, a vision that is as relevant today as it was in 1982. Volcker essentially said, “Look, I have no idea what prices are today. Or what inflation is today. And we won’t have those data for months. But I do know exactly what the spot prices of commodities are.”

In short, what Chairman Volcker did was to base monetary policy on the secular pattern of spot commodity prices (the market price of a commodity for current delivery). … It’s very similar to a gold standard, except that Chairman Volcker was using twenty-five commodities instead of just one. Every quarter from 1982 on, monetary policy has been guided by the spot price of a collection of commodities, save for our present period.

It’s easy to see why anyone reading this might think (1) that Laffer himself convinced Volcker to target an index of commodity prices; (2) that that is just what Volcker then proceeded to do; and (3) that subsequent Fed chairs, at least up to Bernanke, did the same. To presume that Moore himself understood his friend to be making these claims, and believed them, hardly seems a stretch.

But are the claims true? As for the first — that Laffer played some part in getting Volcker to adopt commodity-price targeting — Laffer’s own account offers plenty of room for doubt. Note how he merely says that he met with Volcker in ’82, and that he subsequently wrote about Volcker’s “vision of a [commodity] price rule.” Laffer never actually claims to have urged any such rule upon Volcker during the meeting of which he speaks. He merely mentions the meeting, and the subsequent (supposed) change in the Fed’s policy, inviting readers to connect the dots.

More important for our purposes is Laffer’s claim that Volcker did indeed switch to targeting commodity prices. His 1982 op-ed, he says, “outlined” Volcker’s “vision” of a (commodity) price rule. But if one refers to that old op-ed (available by subscription only through ProQuest Historical Newspapers), one finds that it does no such thing. Rather than outlining Volcker’s vision, the authors propose to test their own theory of what Volcker’s Fed had been up to. “If the Fed is now on a price rule,” they say (my emphasis), “interest rates and the price level can be stabilized. But growth rates in money will become volatile.” They then go on to show how, for the preceding three or four months, the Dow-Jones spot commodity price index had been relatively stable, while M1 growth had been relatively volatile. Q.E.D. (Not.)

As for evidence that Paul Volcker was actually aware that the Fed had been targeting commodity prices, Laffer and Kadlec admit that “it is impossible, short of an official announcement, to be certain that the pursuit of a price rule will continue.” Given the short time span of their “evidence” for such a rule, they might well have written “exists” instead of “will continue.” That is, they might have admitted that there is no clear evidence that Vocker was deliberately targeting commodity prices. Instead, they offer a statement by Volcker saying he did not think that the Fed had “any alternative but to attach much less than usual weight to movements in M1 over the period immediately ahead.” I trust that my readers know the difference between a Fed decision to assign less weight to M1 as an indicator of monetary conditions and a decision to target a commodity price index.

In their 2010 book, in contrast, Laffer and Moore “quote” Volcker as “essentially” saying that he had “no idea what prices are today. Or what inflation is today. And we won’t have those data for months. But I do know exactly what the spot prices of commodities are.” But this begs the question, or rather two questions. First, if Volcker did “essentially” say something like this, why not quote his actual words? Second, why did Laffer and Kadlec not refer to Volcker’s more explicit statement in their 1982 op-ed? The parsimonious answer, I’m afraid, is that Volcker never actually said anything of the sort.*

We have, furthermore, at least one authority who says that Volcker never said anything of the sort, and that authority happens to be none other than … Arthur Laffer! Writing for Reason in May 1983, Laffer tells a story quite different from the one he relates in his and Moore’s 2010 book. “In response to our October 1982 Wall Street Journal article,” he says here,

Chairman Paul Volcker pointed out the difficulty of focusing on commodity price indices at a time when many commodity prices have been severely depressed by the recession. Until the economy recovers, the Fed will have to monitor what Volcker calls “various indicators of inflationary pressures.” The recent fall in the price of gold, decline in commodity price indices and long-term interest rates, and the strength of the dollar on foreign exchange markets all suggest continued success in the Federal Reserve’s efforts to stabilize the price level.

In other words, while Mr. Volcker believed that the Fed could no longer attach much weight to M1, he did not believe it could attach much weight to commodity-price movements, either. Instead, by suggesting that the Fed should monitor “various indicators of monetary pressure,” with no particular emphasis on either monetary aggregates or commodity prices, Volcker was proposing that it do more or less what is has been doing in recent decades, rather than what Stephen Moore suggests it ought to do.

Which brings us to the last of Mr. Laffer’s claims, to wit: that the Fed was targeting commodity prices, not just in 1982, but until not long before 2010, when Return to Prosperity was published. Regarding the period until 1992, we have evidence contradicting the claim from Wayne Angell, the one prominent Federal Reserve official (he served on the Board of Governors from 1986 until 1992) who clearly did favor commodity-index stabilization. In a 1987 paper he wrote on that subject for the Lehrman Institute, Angel observes:

The Fed has always tracked the movements in all reliable measures of economic activity, and will continue to do so. However, I am suggesting an expanded role for commodity prices. I am proposing a commodity price guide to adjust short run money growth target ranges. I believe that commodity prices can provide a reliable early signal of inflationary (or deflationary) pressures.

Clearly, whatever the Fed was doing before Angel wrote this, it was not already following his advice.

In a later, 1992 paper, this time for The Cato Journal, Angell states that it was only “during the period from spring to autumn 1989 [that] for the first time, the Federal Reserve used commodity prices effectively to improve the conduct of monetary policy.” He goes on to say, however, that by late 1989 “events had changed,” causing him to dissent from the Fed’s December 1989 decision to lower its policy target.

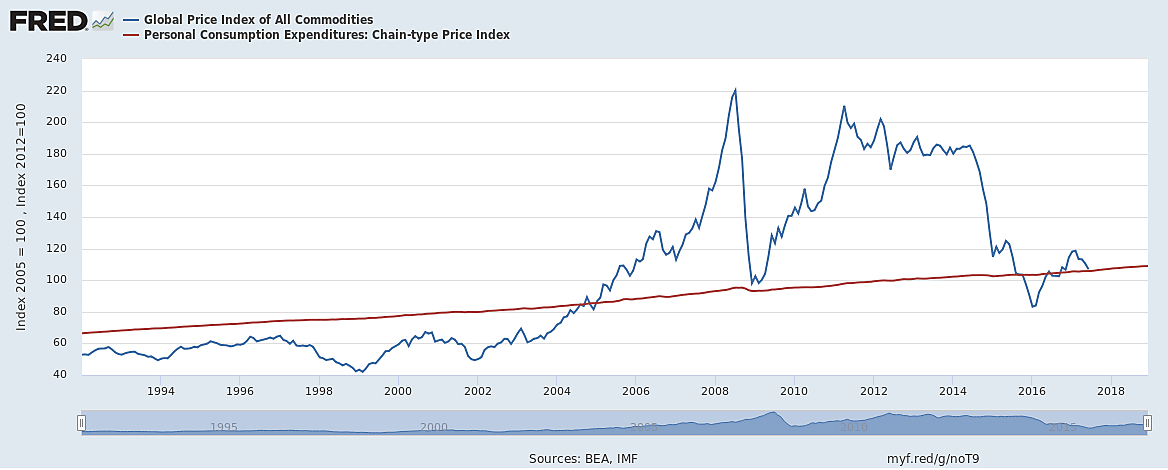

As for what the Fed did after 1992, rather than devote many words to establishing that it continued to refrain from stabilizing any broad index of commodity prices, I hope that a single FRED graph will suffice for the purpose. The graph compares the IMF’s global commodity price index (FRED’s broadest measure of commodity prices), to the (broad) PCE index, which is the Fed’s preferred broad price-level measure, recognized by all to have informed the Fed’s rate decisions. The chart begins in 1992, the earliest year for which the commodity price index values are available.

To conclude: despite what Stephen Moore has written, there’s no evidence that either Paul Volcker or any later Fed chair ever deliberately “linked Fed monetary policy to real-time changes in commodity prices.” In claiming otherwise, Mr. Moore appears to have leaned heavily on Art Laffer’s own relatively recent recollection of the Volcker years, which are to some extent contradicted by Laffer’s own, earlier testimony. The moral of the story, if there is one, is that, should Mr. Moore secure a seat on the Federal Reserve Board, he would be wise to consult other sources for information on monetary history and, for that matter, on how the Fed should or shouldn’t conduct monetary policy.

_____________________

*Nor does a quick perusal of either the Volcker-era FOMC transcripts or Volcker’s published memoir supply any evidence that Volcker deliberately sought to stabilize commodity prices.