That’s the title of a paper I’m writing for this year’s Cato Monetary Conference (the subtitle is “How the Federal Reserve Misrepresents Monetary History”). For it, I’d be very grateful to anyone who can point me to examples (the more egregious the better) of untrue or misleading statements regarding U.S. monetary history in general, and the Fed’s performance in particular, in official Fed publications or in lectures and speeches by Federal Reserve officials.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Monetary Policy

The Sage of Equipoise

Related Tags

What is a Bitcoin?

That’s the title of a live radio program I took part in this Tuesday on KCUR, Kansas City’s NPR radio station. Josh Zerlan, COO of Butterfly Labs (which manufactures Bitcoin mining hardware) also took part in the segment, as did several persons who called in with questions. The program was very ably hosted by Brian Ellison.

When I first took a good look at Bitcoin about a year ago, it could claim only about 1000 registered bitcoin-accepting merchants. Today the figure is 10,000. I wouldn’t be surprised if it reached 100,000 in another year.

Related Tags

Booms, etc.: Addendum

In case anyone might otherwise miss it, I have added an addendum to my last post, responding to Scott Sumnner’s reply to it.

Related Tags

Booms, Bubbles, Busts, and Bogus Dichotomies

Having learned my monetary economics from both the great monetarist economists and their Austrian counterparts, I’ve always chafed at the tendency of people, including members of both schools, to treat their alternative explanations of recessions and depressions as being mutually exclusive or incompatible. According to this tendency, a downturn must be caused either by a deficient money supply, and consequent collapse of spending, or by previous, excessive monetary expansion, and consequent, unsustainable changes to an economy’s structure of production.

During the 1930s and ever since, this dichotomy has split economists into two battling camps: those who have blamed the Fed only for having allowed spending to shrink after 1929, while insisting that it was doing a bang-up job until then, and those who have blamed the Fed for fueling an unsustainable boom during the latter 1920s, while treating the collapse of the thirties as a needed purging of prior “malinvestment.” As everyone except Paul Krugman knows, the Austrian view, or something like it, had many adherents when the depression began. But since then, and partly owing (paradoxically enough) to the influence of Keynes’s General Theory, with its treatment of deficient aggregate demand as the problem of modern capitalist economies, the monetarist position has become much more popular, at least among economists.

It is, of course, true that monetary policy cannot be both excessively easy and excessively tight at any one time. But one needn’t imagine otherwise to see merit in both the Austrian and the monetarist stories. One might, first of all, believe that some historical cycles fit the Austrian view, while others fit the monetarist one. But one can also believe that both theories help to account for any one cycle, with excessively easy money causing an unsustainable boom, and excessively tight money adding to the severity of the consequent downturn. I put the matter to my undergraduates, who seem to have little trouble “getting” it, like this: A fellow has an unfortunate habit of occasionally going out on a late-night drinking binge, from which he staggers home, stupefied and nauseated. One night his wife, sick and tired of his boozing, beans him with a heavy frying pan as he stumbles, vomiting, into their apartment. A neighbor, awakened by the ruckus, pokes his head into the doorway, sees our drunkard lying unconscious, in a pool of puke, with a huge lump on his skull. “What the heck happened to him?,” he asks. Must the correct answer be either “He’s had too much to drink” or “I bashed his head”? Can’t it be “He drank too much and then I bashed his head”? If it can, then why can’t the correct answer to the question, “What laid the U.S. economy so low in the early 1930s?” be that it no sooner started to pay the inevitable price for having gone on an easy money binge when it got walloped by a great monetary contraction?

In insisting that one shouldn’t have to blame a bust either on excessive or on deficient money, I do not mean to expose myself to the charge of making the opposite error. My position isn’t that excessive and tight money must both play a part in every bust. Nor is it that, when both have played a part, each part must have been equally important. The question of the relative historical importance of the two explanations is an empirical one, concerning which intelligent and open-minded researchers may disagree. The point I seek to defend is that those who argue as if only one of the two theories can possibly have merit cannot do so on logical grounds. Instead, they must implicitly assume either that central banks tend to err in one direction only, or that, if they err in both, only their errors in one direction have important cyclical consequences.

The history of persistent if not severe inflation on one hand and of infrequent but severe deflations on the other surely allows us to reject the first possibility. What grounds are there, then, for believing that money is roughly “neutral” when its nominal quantity grows more rapidly than the real demand for it, but not when its quantity grows less rapidly than that demand, as some monetarists maintain, or for believing precisely the opposite, as some Austrian’s do? New Classical economists, whatever their other faults, are at least consistent in assuming that money prices are perfectly flexible both upwards and downwards, leaving no scope for any sort of monetary innovations to affect real economic activity except to the extent that people observe price changes imperfectly and therefore confuse general changes with relative ones. Both old-fashioned and “market” monetarists, on the other hand, argue as if the economy has to “grope” its way slowly and painfully toward a lowered set of equilibrium prices only, while adjusting to a raised set of equilibrium prices as swiftly and painlessly as it might were a Walrasian auctioneer in charge. Many Austrians, on the other hand, insist that monetary expansion necessarily distorts relative prices, and interest rates especially, in the short-run, while also arguing as if actual prices have no trouble keeping pace with their theoretical market-clearing values even as those values collapse.

Of these two equally one-sided treatments of monetary non-neutrality, the monetarist alternative seems to me somewhat more understandable. For monetarists, like New Keynesians, attribute the non-neutral effects of monetary change to nominal price rigidities. They can thus argue, in defense of their one sided view, that it follows logically from the fact that certain prices, and wage rates especially, are less rigid upward than downward. That’s the thinking behind Milton Friedman’s “plucking” model, according to which potential GNP is a relatively taught string, and actual GNP is the same string yanked downward here and there by money shortages, and his corresponding denial of the existence of business “cycles.” But “less rigid” isn’t the same as “perfectly flexible” or “continuously market clearing.” So although Friedman’s perspective might justify his holding that a given percentage reduction in the money stock will have greater real consequences than a similar increase, other things equal, it alone doesn’t suffice to sustain the view that excessively easy monetary policy is entirely incapable of causing booms. What’s more, as Roger Garrison has pointed out, the fact that real output appears to fit the “plucking” story doesn’t itself rule out the presence of unsustainable booms, which (if the Austrian theory of them is correct) involve not so much an expansion of total output as a change in its composition.

Austrians, in contrast, tend to attribute money’s non-neutrality, not to general price rigidities, but to so-called “injection” effects. In a modern monetary system such effects result from the tendency of changes in the nominal quantity of money to be linked to like changes in nominal lending, and particularly to changes in the nominal quantity of funds being channeled by central banks into markets for government securities and bank reserves. The influence of monetary innovations will therefore be disproportionately felt in particular loan markets before radiating from them to the rest of the economy. It is not easy to see why monetary “siphoning” effects, to coin a term for them, should not be just as non-neutral and important as injection effects of like magnitude. To the extent that the monetary transmission mechanism relies upon a credit channel, that channel flows both ways.

A division of economists resembling that concerning the role of monetary policy in the Great Depression has developed as well in the wake of the recent boom-bust cycle. Only this time, oddly enough, several prominent monetarists and fellow travelers (among them, Anna Schwartz, Allan Meltzer, and John Taylor) have actually joined ranks with Austrians in holding excessively easy monetary policy in the wake of the dot-com crash to have been at least partly responsible for both the housing boom and the consequent bust. With so many old-school monetarists switching sides, the challenge of denying that monetary policy ever causes unsustainable booms, and of claiming, with regard to the most recent cycle, that the Fed was doing a fine job until until house prices started falling, has instead been taken up by Scott Sumner and some of his fellow Market Monetarists.

Sumner, like Milton Friedman, forthrightly denies that there’s such a thing as booms, or at least of booms caused by easy money, to the point of taking exception to a recent statement by President Obama to the effect that, among its other responsibilities, the Fed should guard against “bubbles.” But here, and unlike Friedman, Sumner basis his position, not merely on the claim that prices are more flexible upwards than downwards, but on a dichotomy erected in the literature on asset price movements, according to which upward movements are either sustainable consequences of improvements in economic “fundamentals,” or are “bubbles” in the strict sense of the term, inflated by what Alan Greenspan called speculators’ “irrational exuberance,” and therefore capable of bursting at any time. Since monetary policy isn’t the source of either improvements in economic fundamentals or outbreaks of irrational exuberance, the fundamentals-vs-bubbles dichotomy implies that monetary policy is never to blame for changes in real asset prices, whether those changes are sustainable or not. If the dichotomy is valid, Sumner, Friedman, and the rest of the “monetary policymakers shouldn’t be concerned about booms” crowd are right, and the Austrians, Schwartz, Taylor, and others, including Obama and his advisors, who would hold the Fed responsible for avoiding booms, are full of baloney.

But it isn’t the Austrian view, but the bubbles-vs-fundamentals dichotomy itself, that’s full of baloney. That dichotomy simply overlooks the possibility that speculators might respond rationally to interest rate reductions that look like changes to “fundamental” asset-price determinants, that is, to relatively “deep” economic parameters, but are actually monetary policy-inspired downward deviations of actual rates from their genuinely fundamental (“natural”) levels. Because actual rates must inevitably return to their natural levels, real asset price movements inspired by “unnatural” interest rate movements, though perfectly rationale, are also unsustainable. Yet to rule such asset price movements out one would have to claim either that monetary policy isn’t capable of influencing real interest rates, even in the short-run, or that the temporary interest-rate effects of monetary policy can have no bearing upon the discount factors that implicitly inform the valuation of amy durable asset. Here again, the burden seems too great for mere a priori reasoning to bear, and we are left waiting to set our eyes upon such empirical studies as are capable of bearing it.

In the meantime, it seems to me that there is a good reasons for not buying into Friedman’s view that there is no such thing as a business cycle, or Sumner’s equivalent claim that there is no such thing as a monetary-policy-induced boom. The reason is that there is too much anecdotal evidence suggesting that doing so would be imprudent. The terms “business cycle” and “boom,” together with “bubble” and “mania,” came into widespread use because they were, and still are, convenient if inaccurate names for actual economic phenomena. The expression “business cycle,” in particular, owes its popularity to the impression many persons have formed that booms and busts are frequently connected to one another, with the former proceeding the latter; and it was that impression that inspired Mises and Hayek do develop their “cycle” or boom-bust theory rather than a mere theory of busts, and that has inspired Minsky, Kindleberger, and many others to describe and to theorize about recurring episodes of “Mania, Panic, and Crash.” Nor is the connection intuitively hard to grasp: the most severe downturns do indeed, as monetarists rightly emphasis, involve severe monetary shortages. But such severe shortages are themselves connected to financial crashes, which connect, or at least appear to connect, to prior booms, if not to “manias.” That the nature of the connections in question, and the role monetary policy plays in them, remains poorly understood is undoubtedly true. But our ignorance of these details hardly justifies proceeding as if booms never happened, or as if monetary policymakers should never take steps to avoid fueling them. On the contrary: the non-trivial possibility that an ounce of boom prevention is worth a pound of quantitative easing makes worrying about booms very prudent indeed, and prudent even for those who believe that monetary shortages are by far the most important proximate cause of recessions and depressions.

Does my saying that Scott and others err in suggesting that monetary policymakers ought not to worry about stoking booms mean that I also disagree with Scott’s arguments favoring the targeting NGDP? Not at all. I’m merely insisting that a sound monetary policy or monetary system is one that avoids upward departures of NGDP from target just as surely as it does downward ones. Nor do I imagine that Scott himself would disagree, since his preferred NGDP targeting mechanism would automatically achieve this very result. But I worry that other NGDP targeting proponents have allowed themselves to become so wrapped up in recent experience, and so inclined thereby to counter arguments for monetary restraint, that they have allowed themselves either to forget that a time will come, if it hasn’t come yet, when such restraint will be just the thing needed to keep NGDP on target, or to treat Scott’s boom-denialism as grounds for holding that, while there can be too little NGDP, there can’t really be too much. (Or, what is almost as bad, that there can’t be too much so long as the inflation rate isn’t increasing, which amounts to tacitly abandoning NGDP targeting in favor of inflation targeting whenever the the latter policy is the looser of the two.) I urge such “monetarists” to recall the damage Keynes did by taking such a short-term view, while disparaging those who worried about the long run. “Keynesiansim” thus became what Keynes himself never intended it to be, which is to say, a set of arguments for putting up with inflation. Let’s not let Market Monetarism become perverted into set of arguments for putting up with unsustainable booms.

____________________________________

Addendum: Scott has responded, claiming that I am wrong in portraying him as a money-induced unsustainable boom denialist. I appreciate his attempts to reassure me, and yet can’t help thinking that he has nevertheless supplied some reasons for my having characterized his thinking as I did. For example, when Scott writes that “asset prices should reflect fundamentals. Interest rates are one of the fundamental factors that ought to be reflected in asset prices. When rates are low, holding the expected future stream of profits constant, asset prices should be high. Bubbles are usually defined as a period when asset prices exceed their fundamental value. If asset prices accurately reflect the fact that rates are low, then that’s obviously not a bubble,” he certainly seems to accept the bubbles-vs.fundamentals dichotomy about which I complain above, with its implicit exclusion of the possibility of a boom based on lending rates that have been driven by “unnaturally” low by means of excessively easy money. Scott only reinforces this interpretation by further observing, in the same post, that “[i]t’s not clear what people mean when they talk of “artificially” low interest rates. The government doesn’t put a legal cap on rates in the private markets, in the way that the city of New York caps rents.” Now if that isn’t sweeping aside the whole Wicksellian apparatus, with its distinction between “natural” and “actual” interest rates, then I don’t know what is.

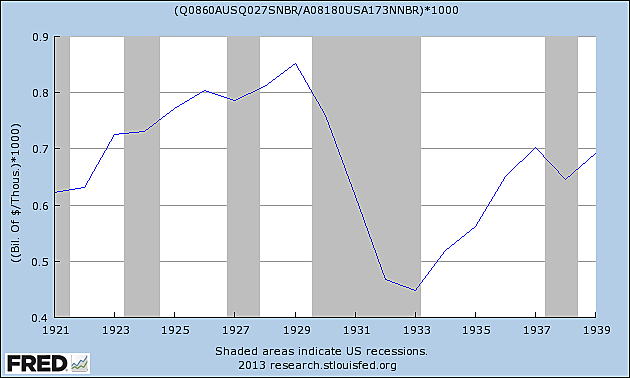

Also, while Scott protests that he does not deny a possible role for easy money in fueling booms, it’s far from evident that he considers this something other than a merely theoretical possibility. He denies (appealing again to the bubbles-vs.-fundamentals dichotomy), that monetary policy played any part in the Roaring Twenties (while asserting that NGDP per capita fell during that decade, though that isn’t my understanding*); and he denies that it played any part in the recent housing boom. With respect to the latter boom he observes, in response to a commentator, that “a housing boom is just as likely to occur with 3% trend NGDP growth as 5% NGDP growth. Money is approximately superneutral. I completely reject the notion that Fed policy is mostly to blame for the housing bubble–it was bad public (regulatory) policies plus stupid decisions by private actors. I’m not saying Fed policy had no effect, but it was a minor factor.” Scott’s claim here, though not altogether wrong as a claim about comparitive steady states, might nonetheless be taken to suggest that there’s little reason to be concerned about adverse effects, apart from inflation, of faster than usual NGDP growth. And this view in turn encourages people to think that, when NGDP grows more rapidly than usual, there’s no harm in sitting back and enjoying it so long as it doesn’t raise the inflation rate much. That is, it encourages them to favor replenishing the punchbowl whenever the party get’s dull, but not removing it when the party starts getting wild.**

Regarded as empirical claims only, Scott’s assertions may of course be valid. But I think the evidence from these and other quotes from him suggests that, while he clearly believes that easy money can influence interest rates, he does not believe, as a matter of theory, and based largely on his acceptance of the bubble-fundamentals dichotomy along with the EMS, as well as his related inclination to brush-aside Wicksell’s arguments as to the possibility as well as the unsustainability of “unnatural” changes in interest rates, that by doing so it can contribute to an unsustainable asset boom.

*Here, for what it’s worth, is the plot I get when I divide nominal NGDP (millions) by population (thousands) using stats from FRED’s macrohistory data base:

**Previously I put the matter here in stronger terms that I now see were unjustified. Sorry, Scott! (Added 10/3/2013 at 9:36PM).

Related Tags

What Bank Intermediation Means

As part of my relentless (some will say obsessive) quest to stamp-out fallacies perpetrated by the 100-percent reserve bunch, I found myself engaged in a discussion with some of them in the comments section of my last post. As the discussion took place some days after that post was published, I hope I may be pardoned for reproducing parts of it, in the hope that doing so might further my overarching objective.

The discussion was prompted by a remark from 100-percenter Paul Marks, who insisted (with his usual emphasis) that “Total borrowing (of all types) must never be greater than total REAL savings of PYSICAL [sic] money. …I repeat that I am NOT making a legal point — I am making a moral and logical one.” In reply I wrote as follows:

Paul, what you are saying makes no sense at all. It is the very nature of lending and borrowing of “physical” assets through intermediaries that the value of financial assets or IOUs tends to exceed that of the physical assets involved. I lend a cow to A, an intermediary, in return for A’s promise to return the cow to me with interest; A lends the same cow to B, in return for a like promise from B. So: one cow, two promises, no harm, no foul.

I then added,

Just to be clear, Paul, in case the “morality” of intermediated lending should not be sufficiently evident: In the example above, I understand that A is acting as my agent; because I am not in a position to expend resources to discover a worthy borrower to whom I may lend my cow, with reasonable assurance of having it returned with interest, or because I am otherwise unable or unwilling to execute the necessary contracts myself, I allow A to take on these tasks for me, in return for his own commitment to repay my principle with interest.

Where loans of “physical” money are involved, the fungibility of that money allows a bank–which is just a name for an intermediary of money loans–to assemble loans from numerous creditors, and to lend funds so assembled to an equally diverse set of borrowers, all of which serves to reduce, ceteris paribus, the banker’s prospects of being unable to meet his various commitments, lowering in turn the credit risk borne by individual bank creditors.

For centuries persons with idle base money balances have found it convenient to relinquish them to bankers as a means for earning interest on such balances with less risk than they would incur by lending them directly, while also (in cases in which deposits are made in exchange for a bank’s demandable debt instruments) having access to means of payment often far more convenient than physical (narrow) money itself.

Of course, as with all forms of lending, lending through banks is not risk free. But that hardly makes such lending either unethical or imprudent. Those who, rather than wishing merely to oppose such regulatory interventions as serve to augment artificially the prospects of bank failures and financial crises, plead instead for banning bank-intermediated lending altogether, though they affect to argue as proponents of freedom and morality, in fact seek to arbitrarily limit the scope of freedom of contract, and by doing so make themselves far more deserving of the charge of immorality than the bankers whom they so loftily–and so uncomprehendingly–criticize.

Reacting to my first remark, perhaps without having read the second, Mike Sproul wrote:

Except that if B doesn’t pay A, and A doesn’t pay you, there is both harm and foul. If the only security for A’s IOU is A’s possession of B’s IOU, then you would insist that B’s IOU be signed over to you when A lent the cow to B. Either that, or you would have placed 1 cow’s worth of lien on A’s other property before accepting A’s IOU in the first place. Try it with a house sometime, and see if you can get lenders to carry $200,000 worth of IOU’s based only upon a $100,000 house.

To which I observed:

Like I said, all lending is risky. And of course (in the absence of government bailouts) intermediaries don’t survive if they continue to make excessively risky or insufficiently secured loans. The tendency, when it comes to banking, for some to hold the industry to be either inherently untenable or immoral or both because banks will occasionally fail is frankly silly. Applied to industry in general, this tendency would have it that we should put an end to all business activity, on the grounds that some people are bound to lose their shirts otherwise!

No one, in any event, is “forced” to transact with a fractional reserve bank. No law, so far as I am aware, has ever prohibited the establishment of 100-percent warehouse alternatives. (Please don’t bring up deposit insurance: what I am saying goes for the long history predating both that and TBTF.) No law prevents anyone from keeping cash in a safe or safety deposit box. To the extent that the law has ever had any say regarding bank’s [sic] reserve-holding decisions, that say has ever been one commanding banks to maintain some minimum positive reserve ratio–never a “maximum” ratio! And of the few important 100-percent “banks” ever established, almost all have been government sponsored arrangements, usually subsidized or otherwise propped up by laws banning would-be fractional reserve rivals.

I do sympathize with those younger students of economics, and of Austrian economics especially, who, having fallen under the sway of anti-fractional reserve propaganda disseminated by Rothbardians and their fellow travelers, have been tempted to jump on the anti-FRB bandwagon. But for the grown-ups responsible for so tempting them, I confess I have nothing but contempt. The a‑priori grounds upon which they condemn FRB are utterly without merit, while a superabundance of empirical evidence flatly contradicts their positions. They are to Austrian economics what the Flat Earth Society is to geology, which is to say (to employ Leland Yeager’s expression): an embarrassing excrescence.

I urge readers of freebanking.org who agree with me, and who know some of the misinformed students to whom I refer, to share this exchange with them, in the hope that it may contribute toward their eventual, successful deprogramming. We can, of course, never hope to purge Austrian economics entirely of the 100-percent-reserve bacilli by which it has become infected in recent years. But we can at least hope to build up such a core of well-informed antibodies as may eventually prevent those bacilli from doing any more harm to the main body of Austrian thought than the occasional e‑coli does to an otherwise robust digestive tract.

Related Tags

A Theory of Banking Made Out of Thin Air

Instances of self-styled Austrian economists bungling their banking theory seem almost as common these days as instances of theologians bungling their cosmology were six centuries ago. One such instance, by the Cobden Centre’s Sean Corrigan, occurs in the course of a long and meandering series of posts inspired by a four-way debate he took part in, with yours truly attending, at Oxford’s Divinity School this May:

[I]magine that I take your IOU to the bank and that [sic] peculiar institution registers my claim upon its (largely intangible) resources in the form of a demand liability of the kind which–by custom, if not by legal privilege–routinely passes in the marketplace as money. Your promissory note–a title to a batch of future goods [sic] not yet in being–has now undergone what we might facetiously call an ‘extreme maturity transformation’ which it [sic] has conferred upon me the ability to bid for any other batch of present goods of like value without further delay. It should, however, be obvious that no such goods exist since you have not had time to generate any replacements for the ones whose use I, their [sic] lender [sic], supposedly forswore until such a time as your substitutes are ready to used [sic] to fulfil [sic] your obligations, something we agreed would be the case only at some nominated [sic] point in the future.

More claims to present goods than goods themselves now exist…and thus the actions we may now simultaneously undertake have become dangerously incongruous [sic]. Our [plans] have become instead a cause of what is an inflationary conflict no less than would be the case if I had sold you my place at the head of the queue for the cinema only to try and barge straight past you in a scramble for the seat in question.

Even setting aside the typos and malapropisms, Corrigan’s prose isn’t likely to inspire anyone to twine a garland around him for his lucidity.* But one thing that is clear is that the bank lending that he has in mind involves three parties only: the banker, the borrower, and a debtor whose IOU to the borrower serves as the borrower’s collateral. For the sake of concreteness, let’s call them the banker, the miller, and the baker; and let’s imagine further that the miller, having offered the baker a ton of flour in exchange for a $101 30-day promissory note, uses the note to secure a $100 loan from the banker.

According to Corrigan the loan thus secured is inflationary because it allows the miller to take part in the “scramble” for present goods, even though he got the loan in exchange for “a title to a batch of future goods not yet in being.” In fact a promissory note or IOU isn’t a “title” to anything, much as Austrians may like calling things “titles” that aren’t such. It is, well, a promise to pay. And it is a promise to pay, not goods, but money. Let us grant, nevertheless, that the note in question stands for goods–loaves of bread, for instance–that have yet to be produced or put on the market, the presumption being that bread will only eventually be made from the flour that was exchanged for the promise, to be put on the market at some still later date. Consequently the loan, and the extra demand for goods that it unleashes, instead of coinciding with an increase in the supply of goods, anticipates such an increase, and to that extent seems bound to raise prices. Bank lending appears analogous to creating fake “tickets” to an already fully-booked performance, allowing the new credit recipients to secure present goods, despite a lack of voluntary savings, simply by bidding goods away from others, that is, by forcing others to consume less, just as holders of fake tickets might take up seats that ought to have gone to holders of legitimate ones.

But the appearance is deceiving, for it depends crucially on Corrigan’s having failed to consider all of the parties that usually take part whenever a competitive bank makes a loan. To see this, we need only consider our imaginary banker’s fate if he makes the loan in question without anyone’s cooperation save that of the miller, who is supposed to repay the loan, and the baker, whose IOU secures the loan in case the miller defaults. The banker’s fate hinges on the fact that bank borrowers borrow money, not to hold, but to spend. So once our miller has $100 credited to his account, he uses it to purchase wheat or other supplies, or to pay his workers, or to settle accounts due–in short, to make whatever payments he cannot afford to put off making for another 30 days–payments that compelled him to borrow money in the first place. So the miller writes checks, and writes them quickly, to the tune of $100. And those checks are paid to persons who, if the banking system is competitive, are likely to deposit them in rival banks. Those banks in turn return the checks for payment, directly or through a bank clearinghouse. So by lending $100 to the miller, the banker generates $100-worth of claims for immediate payment against his institution. Those claims, it goes without saying, cannot be settled directly using the baker’s promissory note, which has yet to mature. They must be settled in cash, which means that the bank must either have such cash on hand, or fail.

If the bank fails, it obviously hasn’t been able to get away with creating credit “out of thin air,” and presumably there will not be many banks rushing to replicate its irresponsible behavior. If, on the other hand, the bank has the cash needed to avoid failing, the obvious question arises: where does the cash come from? Two answers suggest themselves. One is that it comes from the bank owners themselves, that is, from capitalists. The other is that it comes from persons who deposited it with the bank, presumably in return for services or a share of its interest earnings or both. In either case, it should be apparent that a competitive bank cannot lend, or rather that it cannot lend and profit by it, unless it has, or quickly gets hold of, cash reserves at least equal to the amount of the loan. That means, in turn, that for a bank to lend someone has to have engaged in prior voluntarily saving, by refraining from spending or from otherwise cashing in their own claims against it. Our banker cannot, in other words, simply create loans out of thin air, and thereby drive prices upward. Instead, if his business is to survive he must act as a go-between or intermediary, lending to the miller only what he has induced others to lend to him. These ultimate suppliers of bank credit, by refraining from consuming, place downward pressure on prices precisely equal to the upward pressure stemming from the banks’ lending. By airbrushing them out of his account of the workings of a typical bank, Corrigan succeeds in painting a picture of the banking business that’s as misleading as it is lurid.

All this, of course, refers only to ordinary commercial bankers–bankers who must do business the hard way, by competing head-on with dozens if not hundreds or even thousands of more-or-less equally privileged rivals. It doesn’t apply to central bankers who, by being able to print-up arbitrary amounts of their economies’ ultimate cash reserve asset, are indeed capable of making loans “out of thin air,” without having to struggle to first gather funding from others. This distinction is what gives central bankers their extraordinary power to do either good (as their proponents imagine them doing) or harm (as they tend to do, more often than not, in fact). By suggesting, in short, that there is no difference between the credit-creating capacity of ordinary commercial banks and that of central banks, accounts like Corrigan’s do a great disservice, by making it harder for people to recognize the unique threat posed by today’s monopoly suppliers of irredeemable paper currency.

Addendum (8/12/13): A correspondent has alerted me to this post, accusing me of having joined Paul Krugman and others in making a “sport” of bashing Austrian economics, and suggesting that I have failed in the post above and elsewhere to recognize the difference between demand and savings deposits, only the last of which (according to the Austrians I criticize) represent true savings. In fact, the distinction in question is absolutely irrelevant to my argument above, the point of which is that a competitive bank cannot get away with creating credit out of thin air. Instead it can afford to lend only to the extent that others save with it. Whether the savings come to a bank in the shape of “demand” or “time” deposits matters only to the extent that it influences the length of time for which the savings in question are likely to remain at the bank’s disposal. The bank is responsible for limiting its credits to amounts consistent with the total extent of credit supplied to it by its liability holders, allowing also for the timing of withdrawals. A banker that misjudges the timing in question exposes his bank to the same risk of failure that confronts one who attempts to extend credit without having received any prior deposits. So whether a bank derives its funding from demand or from time deposits, the conclusion stands: if the bank is to survive, the bank’s lending must be limited to the amount of real savings it has on hand.

As for my being just another anti-Austrian economist, that’s a calumny: I am a fan of Austrian economics, as embodied in the works of such great Austrian pioneers as Menger, Mises, and Hayek, as well as in those of many living members of the school. What deserves to be ridiculed is the unending tide of junk written, mostly on the internet, by people who label themselves “Austrian economists” despite appearing to know only as much about economics as I know about string theory, which is to say, next to nothing.

________________________________

*Some of Corrigan’s more florid passages read as if concocted by tossing one copy each of Finnegans Wake, Sartor Resartus, and the Communist Manifesto into a blender and hitting “Pulse” once or twice. Consider: “Among other enormities, the fact that production must necessarily precede consumption and that it is the first which comprises the creation of wealth and the second which encompasses its destruction, was far beyond the ken of the spoiled Bloomsbury elitist who exhibited a life-long contempt of the aspirations and mores of the bourgeoisie and who hence imagined that policy was at its finest when, like an over-indulgent aunt, it was pliantly accommodating the otherwise ‘ineffective’ demand being volubly expressed by the old dame’s petulant nephew as he stamped his foot in the tantrum he was throwing up against the sweet-shop window.” When I encounter such prose I cannot quite decide whether to throw up a tantrum myself, or simply to throw up.