At the Weekly Standard, Chris Conover explains.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

General

‘Stupid’ ObamaCare Provision Offends America’s Highest Caste: Congress

ObamaCare’s gravest sin may be that it has offended America’s highest caste: members of Congress and their staffs. Thanks to an amendment by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R‑IA), the law provides:

the only health plans that the Federal Government may make available to Members of Congress and congressional staff with respect to their service as a Member of Congress or congressional staff shall be health plans that are created under this Act…or offered through an Exchange established under this Act…

In effect, ObamaCare throws members of Congress out of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (where most members and staff obtain health insurance) and offers them no other choice but to enroll in coverage through one of ObamaCare’s Exchanges. But here’s the kicker: though the federal government currently pays thousands of dollars of the cost of the congresscritters’ FEHBP coverage, neither ObamaCare nor any other federal law authorizes the feds to apply that money toward a congresscritter’s Exchange premiums. Today’s New York Times reports:

David M. Ermer, a lawyer who has represented insurers in the federal employee program for 30 years, said, “I do not think members of Congress and their staff can get funds for coverage in the exchanges under existing law.”

So ObamaCare essentially delivers a pay cut to members and staff in the neighborhood of $5,000 for single employees and $10,000 for families.

Even congressional Democrats who voted for ObamaCare are freaking out (and pointing fingers). Again, the New York Times:

Representative Diana DeGette, Democrat of Colorado, said the Senate was responsible for the provision requiring lawmakers and many aides to get insurance in the exchanges.

“We had to take the Senate version of the health care bill,” Ms. DeGette said. “This is not anything we spent time talking about here in the House.”

Another House Democrat, speaking on condition of anonymity, said, “This was a stupid provision that never should have gotten into the law.”

You’d never know they had a choice, and voted for this provision anyway.

Finally, the Times notes, “The issue is politically charged because the White House and Congress are highly sensitive to any suggestion that lawmakers or their aides are getting special treatment under the health law” and, “Aides who work for Congressional committees and in leadership offices, like those of the speaker of the House and the majority and minority leaders of the two chambers, are apparently exempt — though neither Congress nor the administration has said for sure.” That creates the potential for a sneaky, backdoor way that ObamaCare supporters — say, the Senate Democrats who set budgets for congressional offices — could shield their staff from ObamaCare: shift staff from personal to committee and leadership offices.

Or, the White House could just decide to make the same contribution to their Exchange coverage, statute be damned. It wouldn’t be the first time this White House tried to protect ObamaCare by spending money that Congress never authorized.

Congressional watchdogs, be on the lookout.

Related Tags

Cato’s Ivy League Internship

The Wall Street Journal reports:

While some colleges struggle to fill seats, the country’s most selective ones are becoming harder to get into. Seven of the eight Ivy League schools reported they lowered their acceptance rate for this fall, with Harvard leading the pack by accepting less than 6% of its more than 30,000 undergraduate applicants.

As we’ve noted before, perhaps the only student program more difficult to get into than Harvard is the Cato internship program. This summer we were able to accept 4.9 percent of the more than 800 applicants for internships.

The program’s rigor is similar to the Ivy League, too. But, unlike the Ivy League, Cato interns receive a broad and deep education in the fundamentals of liberty. Each intern is assigned to policy directors at Cato, allowing the intern to delve deeply into a particular area of study. Not only do the interns help Cato scholars with research and work with the conference department to organize policy conferences, debates, and forums, but they attend regular seminars on politics, economics, law, and philosophy, as well as a series of lectures and films on libertarian themes. The interns develop their public speaking skills by presenting policy recommendations and develop their writing skills by drafting letters to the editor and op-eds. After such intense study, they emerge at the end of the summer well equipped to promote and live the ideas of liberty.

Find out more about Cato internships here. Note that the internship program is year-round, and the process is a little less competitive for Fall and Spring internships. We encourage students to consider applying in any season. The deadline for Fall internship applications has passed, and the deadline for Spring is November 1.

Related Tags

Wall Street Journal Condemns OECD Proposal to Increase Business Fiscal Burdens with Global Tax Cartel

What’s the biggest fiscal problem facing the developed world?

To an objective observer, the answer is a rising burden of government spending, which is caused by poorly designed entitlement programs, growing levels of dependency, and unfavorable demographics. The combination of these factors helps to explain why almost all industrialized nations—as confirmed by BIS, OECD, and IMF data—face a very grim fiscal future.

If lawmakers want to avert widespread Greek-style fiscal chaos and economic suffering, this suggests genuine entitlement reform and other steps to control the growth of the public sector.

But you probably won’t be surprised to learn that politicians instead are concocting new ways of extracting more money from the economy’s productive sector.

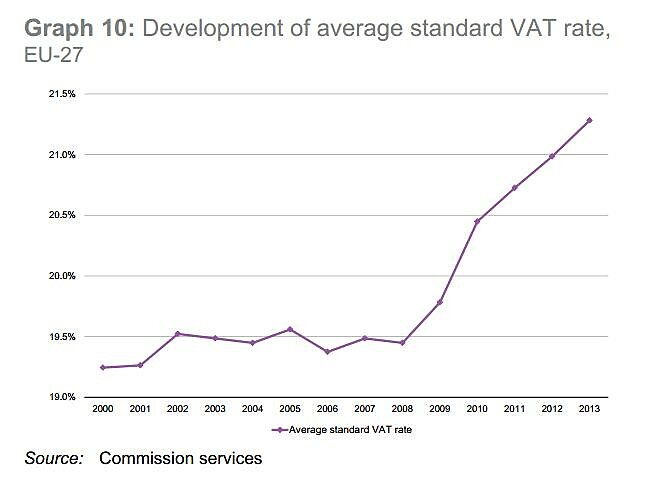

They’ve already been busy raising personal income tax rates and increasing value-added tax burdens, but that’s apparently not sufficient for our greedy overlords.

Now they want higher taxes on business. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, for instance, put together a “base erosion and profit shifting” plan at the behest of the high-tax governments that dominate and control the Paris-based bureaucracy.

What is this BEPS plan? In an editorial titled “Global Revenue Grab,” The Wall Street Journal explains that it’s a scheme to raise tax burdens on the business community:

After five years of failing to spur a robust economic recovery through spending and tax hikes, the world’s richest countries have hit upon a new idea that looks a lot like the old: International coordination to raise taxes on business. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on Friday presented its action plan to combat what it calls “base erosion and profit shifting,” or BEPS. This is bureaucratese for not paying as much tax as government wishes you did. The plan bemoans the danger of “double non-taxation,” whatever that is, and even raises the specter of “global tax chaos” if this bogeyman called BEPS isn’t tamed. Don’t be fooled, because this is an attempt to limit corporate global tax competition and take more cash out of the private economy.

The Journal is spot on. This is merely the latest chapter in the OECD’s anti-tax competition crusade. The bureaucracy represents the interests of

high-tax governments that are seeking to impose higher tax burdens—a goal that will be easier to achieve if they can restrict the ability of taxpayers to benefit from better tax policy in other jurisdictions.

More specifically, the OECD basically wants a radical shift in international tax rules so that multinational companies are forced to declare more income in high-tax nations even though those firms have wisely structured their operations so that much of their income is earned in low-tax jurisdictions.

So does this mean that governments are being starved of revenue? Not surprisingly, there’s no truth to the argument that corporate tax revenue is disappearing:

Across the OECD, corporate-tax revenue has fluctuated between 2% and 3% of GDP and was 2.7% in 2011, the most recent year for published OECD data. In other words, for all the huffing and puffing, there is no crisis of corporate tax collection. The deficits across the developed world are the product of slow economic growth and overspending, not tax evasion. But none of this has stopped the OECD from offering its 15-point plan to increase the cost and complexity of complying with corporate-tax rules. …this will be another full employment opportunity for lawyers and accountants.

I made similar points, incidentally, when debunking Jeffrey Sachs’ assertion that tax competition has caused a “race to the bottom.”

The WSJ editorial makes the logical argument that governments with uncompetitive tax regimes should lower tax rates and reform punitive tax systems:

…the OECD plan also envisions a possible multinational treaty to combat the fictional plague of tax avoidance. This would merely be an opportunity for big countries with uncompetitive tax rates (the U.S., France and Japan) to squeeze smaller countries that use low rates to attract investment and jobs. Here’s an alternative: What if everyone moved toward lower rates and simpler tax codes, with fewer opportunities for gamesmanship and smaller rate disparities among countries?

The piece also makes the obvious—but often overlooked—point that any taxes imposed on companies are actually paid by workers, consumers, and shareholders.

…corporations don’t pay taxes anyway. They merely collect taxes—from customers via higher prices, shareholders in lower returns, or employees in lower wages and benefits.

Last but not least, the WSJ correctly frets that politicians will now try to implement this misguided blueprint:

The G‑20 finance ministers endorsed the OECD scheme on the weekend, and heads of government are due to take it up in St. Petersburg in early September. But if growth is their priority, as they keep saying it is, they’ll toss out this complex global revenue grab in favor of low rates, territorial taxes and simplicity. Every page of the OECD’s plan points in the opposite direction.

The folks at the Wall Street Journal are correct to worry, but they’re actually understating the problem. Yes, the BEPS plan is bad, but it’s actually much less onerous that what the OECD was contemplating earlier this year when the bureaucracy published a report suggesting a “global apportionment” system for business taxation.

Fortunately, the bureaucrats had to scale back their ambitions. Multinational companies objected to the OECD plan, as did the governments of nations with better (or at least less onerous) business tax structures.

It makes no sense, after all, for places such as the Netherlands, Ireland, Singapore, Estonia, Hong Kong, Bermuda, Switzerland, and the Cayman Islands to go along with a scheme that would enable high-tax governments to tax corporate income that is earned in these lower-tax jurisdictions.

But the fact that high-tax governments (and their lackeys at the OECD) scaled back their demands is hardly reassuring when one realizes that the current set of demands will be the stepping stone for the next set of demands.

That’s why it’s important to resist this misguided BEPS plan. It’s not just that it’s a bad idea. It’s also the precursor to even worse policy.

As I often say when speaking to audiences in low-tax jurisdictions, an appeasement strategy doesn’t make sense when dealing with politicians and bureaucrats from high-tax nations.

Simply stated, you don’t feed your arm to an alligator and expect him to become a vegetarian. It’s far more likely that he’ll show up the next day looking for another meal.

P.S. The OECD also is involved in a new “multilateral convention” that would give it the power to dictate national tax laws, and it has the support of the Obama administration even though this new scheme would undermine America’s fiscal sovereignty!

P.P.S. Maybe the OECD wouldn’t be so quick to endorse higher taxes if the bureaucrats—who receive tax-free salaries—had to live under the rules they want to impose on others.

Related Tags

Reality Hits Sunshine State “Accountability”

Former Florida governor Jeb Bush is arguably the leading supporter of both the Common Core national curriculum standards and top-down, standards-and-accountability-based reforms generally. And there is broad evidence that he had success with his overall education program as governor, though that included a sizable—and likely influential—amount of school choice. Given that success, why does the “accountability” piece of his overall program seem to be eroding, with the state school board voting last week to “pad” school grades, for the second year in a row, greatly reducing how many schools are deemed failures? Answering this is crucial to understanding why top-down reforms like Common Core—even if initially offering high standards and strict accountability—almost certainly won’t maintain them.

Once again, we have to visit our ol’ buddies, concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. Put simply, the people with the most at stake in a policy area will have the greatest motivation to be involved in the politics of that area, and in education those are the schooling employees whose very livelihoods come from the system. And being normal people like you or me, what they tend to ideally want is to get compensated as richly as possible while not being held accountable for their performance.

The natural counters to this should be the parents the employees are supposed to serve and the taxpayers footing the bills. But taxpayers have to worry about every part of the state spending pie, and can’t sustain their focus—or motivation—for long on any particular pie slice. Meanwhile, parents are much harder to organize than, say, teachers and administrators, and are only parents of school-aged children for so long. Political advantage: those whom government is supposed to hold accountable.

That said, in Florida it sounds like many parents and taxpayers may be getting fatigued by test-driven school grades, adding onto the power of employee groups. Like we’ve seen in Texas, Florida’s politics may be reflecting a general exhaustion with standards and testing that fails to treat either students, or schools and districts, as unique. In other words, the likely benefits to breaking down such systems are being felt by more parents and “regular” voters, which doesn’t bode well for standards-and-accountability in Florida.

Which brings us to the crucial point about the Common Core. Supporters have a tendency to promise the world with the Core (often neglecting to mention that it provides no accountability itself) largely because they think the standards are very high. But even if they are lofty, and even if they are initially coupled with common tests with high “proficiency” bars—an increasingly big “if”—because of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs the odds of them staying that way are poor. It is a huge problem that Core supporters need to address, even for people who like the idea of “tough” government standards for schools. But sadly, many supporters seem to ignore the problem, choosing instead to tout how supposedly excellent the standards are, and attack as loony opponents who dare to oppose the Core for numerous, very rational reasons.

Unfortunately, it seems a major reason for adopting that tactic is to shield from honest debate a policy that will, by its very nature, impose itself on the entire country. That’s something no one in the country should be happy about.

Related Tags

A Big, Tiny Deal on Student Loans

After a bit of a false start last week, it sounds again like the Senate is on the brink of a bipartisan compromise that will link rates on federal student loans to overall interest rates. Given all the hubbub that’s surrounded the loans, that’s big news. Given the actual change that would take place, it’s tiny.

Based on reports so far, the plan seems to be to eventually peg all undergraduate loans — both the officially “subsidized” and “unsubsidized” — to 10-year Treasury bill interest rates, adding 2.05 percentage points. Today, that would make the interest rate 4.57 percent. However, it appears that the compromise would put rates at 3.85 percent this fall. That’s no doubt a sweetener to appease student interest groups, whose goal is to get the cheapest loans possible regardless of the rest of the economy, and who don’t think a deal pegging student loans to T‑bills is so hot.

To be fair, the deal isn’t hot. It’s barely room temperature. But that’s because it still gives away far too much, not too little. Taxpayer-backed loans that go to almost anyone have been a sweet-sounding disaster, encouraging people to consume education they aren’t willing or able to complete; prodding people who are college-ready to demand things that have little or nothing to do with education; and fueling rampant price inflation throughout the system. And, like last week’s abortive deal, this one appears to eliminate the different rates for the “subsidized” loans — those geared to truly low-income students — and the “unsubsidized” loans that have no income cap. In other words, the student aid system that is already heavily skewed toward the better-off seems likely to become a bit more so.

If this compromise eventually gets signed by the president, it will likely be hailed as a big, bipartisan deal. And maybe politically it would be. But as policy? It would barely register.

Related Tags

America’s Corporate Tax System Ranks a Miserable 94 out of 100 Nations in “Tax Attractiveness”

I’ve relentlessly complained that the United States has the highest corporate tax rate among all developed nations.

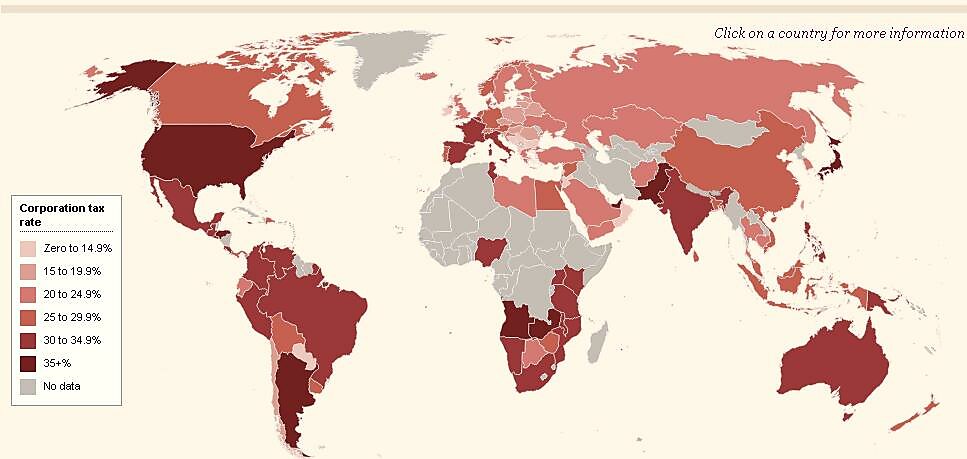

And if you look at all the world’s countries, our status is still very dismal. According to the Economist, we have the second highest corporate tax rate, exceeded only by the United Arab Emirates.

But some people argue that the statutory tax rate can be very misleading because of all the other policies that impact the actual tax burden on companies.

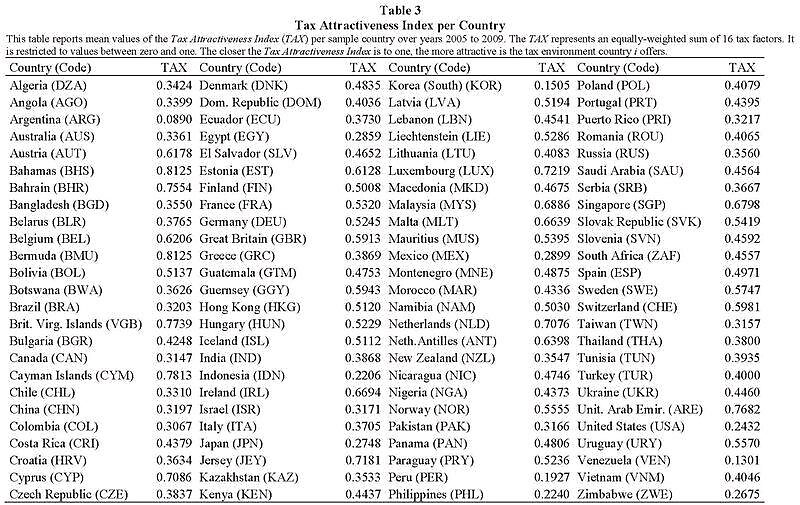

That’s a very fair point, so I was very interested to see that a couple of economists at a German think tank put together a “tax attractiveness” ranking based on 16 different variables. The statutory tax rate is one of the measures, of course, but they also look at policies such as “the taxation of dividends and capital gains, withholding taxes, the existence of a group taxation regime, loss offset provision, the double tax treaty network, thin capitalization rules, and controlled foreign company (CFC) rules.”

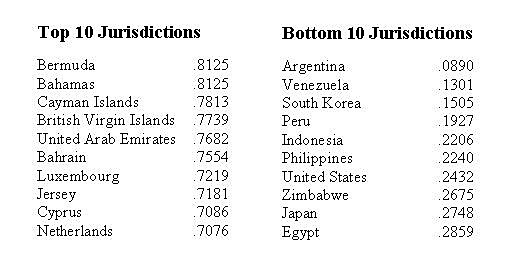

It turns out that these additional variables can make a big difference in the overall attractiveness of a nation’s corporate tax regime. As you can see from this list of top-10 and bottom-10 nations, the United Arab Emirates has one of the world’s most attractive corporate tax systems, notwithstanding having the highest corporate tax rate.

Unfortunately, the United States remains mired near the bottom.

The “good news” is that we beat out Argentina and Venezuela, two of the world’s most corrupt and despotic nations.

Not surprisingly, so-called tax havens dominate the top spots in the ranking. And that’s the case even though financial privacy laws are not part of the equation.

Here are all the scores from the report. They listed nations in alphabetical order, so it’s not very user-friendly if you want to make comparisons. But a simple rule-of-thumb is that any score about .6000 is relatively good and any score below .4000 suggests a country is shooting itself in the foot.

For what it’s worth, Switzerland, Singapore, and Estonia exceed the .6000 threshold, as one might expect, but I was surprised that both Hong Kong and Liechtenstein were in the middle of the pack. Heck, both nations scored worse than France!

But that gives me an opportunity to issue a very important caveat. It’s good to have an attractive corporate tax system, but there are dozens of other factors that help determine a nation’s prosperity and competitiveness. Indeed, fiscal policy is only 20 percent of a country’s score in the Economic Freedom of the World rankings. So not only is it important to also look at other tax policies and the overall burden of government spending to gauge a nation’s fiscal policy, you also need to look at other big factors such as monetary policy, trade policy, and regulatory policy.

As such, even though it’s galling that the American corporate tax system ranks below France (and Italy, Greece, Ukraine, Nigeria, etc), the United States fortunately does better in most other areas. That being said, I’m quite worried that we’ve dropped from 3rd place in the overall Economic Freedom of the World rankings when Bill Clinton left office to 18th place in the most recent rankings, so the trend obviously isn’t very encouraging.

Another caveat to keep in mind that the rankings are for 2005–2009, so some nations will have moved up or down since then. I would be very surprised, for instance, if Cyprus was still in the top 10. And it’s quite like that the U.S. score dropped as well, thanks to the tax increases in Obamacare and the “fiscal cliff” deal.

P.S. I’ve never seen a ranking of nations based solely on personal income taxes, but the Liberales Institut in Switzerland put together a “Tax Oppression Index” for industrialized nations and the United States scored 19th out of 30 nations in that measure of how individual taxpayers are treated.