What’s the biggest fiscal problem facing the developed world?

To an objective observer, the answer is a rising burden of government spending, which is caused by poorly designed entitlement programs, growing levels of dependency, and unfavorable demographics. The combination of these factors helps to explain why almost all industrialized nations—as confirmed by BIS, OECD, and IMF data—face a very grim fiscal future.

If lawmakers want to avert widespread Greek-style fiscal chaos and economic suffering, this suggests genuine entitlement reform and other steps to control the growth of the public sector.

But you probably won’t be surprised to learn that politicians instead are concocting new ways of extracting more money from the economy’s productive sector.

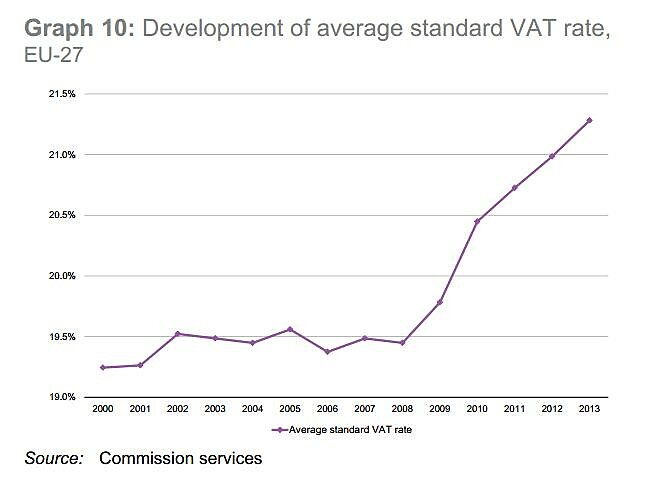

They’ve already been busy raising personal income tax rates and increasing value-added tax burdens, but that’s apparently not sufficient for our greedy overlords.

Now they want higher taxes on business. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, for instance, put together a “base erosion and profit shifting” plan at the behest of the high-tax governments that dominate and control the Paris-based bureaucracy.

What is this BEPS plan? In an editorial titled “Global Revenue Grab,” The Wall Street Journal explains that it’s a scheme to raise tax burdens on the business community:

After five years of failing to spur a robust economic recovery through spending and tax hikes, the world’s richest countries have hit upon a new idea that looks a lot like the old: International coordination to raise taxes on business. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on Friday presented its action plan to combat what it calls “base erosion and profit shifting,” or BEPS. This is bureaucratese for not paying as much tax as government wishes you did. The plan bemoans the danger of “double non-taxation,” whatever that is, and even raises the specter of “global tax chaos” if this bogeyman called BEPS isn’t tamed. Don’t be fooled, because this is an attempt to limit corporate global tax competition and take more cash out of the private economy.

The Journal is spot on. This is merely the latest chapter in the OECD’s anti-tax competition crusade. The bureaucracy represents the interests of

high-tax governments that are seeking to impose higher tax burdens—a goal that will be easier to achieve if they can restrict the ability of taxpayers to benefit from better tax policy in other jurisdictions.

More specifically, the OECD basically wants a radical shift in international tax rules so that multinational companies are forced to declare more income in high-tax nations even though those firms have wisely structured their operations so that much of their income is earned in low-tax jurisdictions.

So does this mean that governments are being starved of revenue? Not surprisingly, there’s no truth to the argument that corporate tax revenue is disappearing:

Across the OECD, corporate-tax revenue has fluctuated between 2% and 3% of GDP and was 2.7% in 2011, the most recent year for published OECD data. In other words, for all the huffing and puffing, there is no crisis of corporate tax collection. The deficits across the developed world are the product of slow economic growth and overspending, not tax evasion. But none of this has stopped the OECD from offering its 15-point plan to increase the cost and complexity of complying with corporate-tax rules. …this will be another full employment opportunity for lawyers and accountants.

I made similar points, incidentally, when debunking Jeffrey Sachs’ assertion that tax competition has caused a “race to the bottom.”

The WSJ editorial makes the logical argument that governments with uncompetitive tax regimes should lower tax rates and reform punitive tax systems:

…the OECD plan also envisions a possible multinational treaty to combat the fictional plague of tax avoidance. This would merely be an opportunity for big countries with uncompetitive tax rates (the U.S., France and Japan) to squeeze smaller countries that use low rates to attract investment and jobs. Here’s an alternative: What if everyone moved toward lower rates and simpler tax codes, with fewer opportunities for gamesmanship and smaller rate disparities among countries?

The piece also makes the obvious—but often overlooked—point that any taxes imposed on companies are actually paid by workers, consumers, and shareholders.

…corporations don’t pay taxes anyway. They merely collect taxes—from customers via higher prices, shareholders in lower returns, or employees in lower wages and benefits.

Last but not least, the WSJ correctly frets that politicians will now try to implement this misguided blueprint:

The G‑20 finance ministers endorsed the OECD scheme on the weekend, and heads of government are due to take it up in St. Petersburg in early September. But if growth is their priority, as they keep saying it is, they’ll toss out this complex global revenue grab in favor of low rates, territorial taxes and simplicity. Every page of the OECD’s plan points in the opposite direction.

The folks at the Wall Street Journal are correct to worry, but they’re actually understating the problem. Yes, the BEPS plan is bad, but it’s actually much less onerous that what the OECD was contemplating earlier this year when the bureaucracy published a report suggesting a “global apportionment” system for business taxation.

Fortunately, the bureaucrats had to scale back their ambitions. Multinational companies objected to the OECD plan, as did the governments of nations with better (or at least less onerous) business tax structures.

It makes no sense, after all, for places such as the Netherlands, Ireland, Singapore, Estonia, Hong Kong, Bermuda, Switzerland, and the Cayman Islands to go along with a scheme that would enable high-tax governments to tax corporate income that is earned in these lower-tax jurisdictions.

But the fact that high-tax governments (and their lackeys at the OECD) scaled back their demands is hardly reassuring when one realizes that the current set of demands will be the stepping stone for the next set of demands.

That’s why it’s important to resist this misguided BEPS plan. It’s not just that it’s a bad idea. It’s also the precursor to even worse policy.

As I often say when speaking to audiences in low-tax jurisdictions, an appeasement strategy doesn’t make sense when dealing with politicians and bureaucrats from high-tax nations.

Simply stated, you don’t feed your arm to an alligator and expect him to become a vegetarian. It’s far more likely that he’ll show up the next day looking for another meal.

P.S. The OECD also is involved in a new “multilateral convention” that would give it the power to dictate national tax laws, and it has the support of the Obama administration even though this new scheme would undermine America’s fiscal sovereignty!

P.P.S. Maybe the OECD wouldn’t be so quick to endorse higher taxes if the bureaucrats—who receive tax-free salaries—had to live under the rules they want to impose on others.