In the Republican debate last night, CNN’s Dana Bash pressed the candidates on how they would deal with Social Security. Senators Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz gave solid answers, explaining that the system was headed toward insolvency, suggesting ways to slow spending growth, and scolding candidates who denied the need for cost-saving reforms.

One of the candidates in denial is Donald Trump. He said, “And it’s my absolute intention to leave Social Security the way it is. Not increase the age and to leave it as is.” Trump is a smart man, who presumably understands accounting, so either he hasn’t bothered to examine the finances of the government’s largest program, or he is willfully providing a false narrative about it.

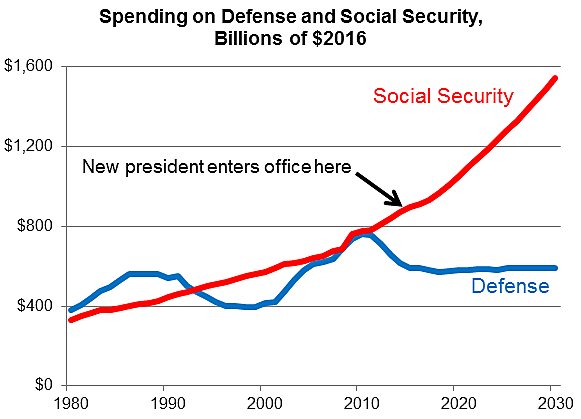

The chart below compares Social Security and defense spending in real 2016 dollars, including Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections going forward. For decades, the two programs have vied for the title of the government’s largest, but the battle is now over. Social Security spending has soared far above defense spending, and it will keep on soaring without reforms.

Defense is a “normal” program, with spending fluctuating up and down over the years in real, or inflation-adjusted, dollars. But Social Security has taken off like a rocket, and it is consuming more taxpayer resources every year. The government spent the same amount on defense and Social Security in 2008, but it will be spending twice as much on the latter program by 2023.

When the next president enters office in 2017, he will start planning his 2018 budget. In that year, Social Security will become the first trillion-dollar program, and it will be gobbling up an additional $60 billion or so every single year. Where will all the money come from? Pointing only to “waste, fraud, and abuse,” as Trump does, wastes our time, abuses our intelligence, and is a fraudulent story line to peddle.

Data notes: CBO baseline projections to 2026, then real defense spending assumed fixed after that, while real Social Security spending is assumed to increase at the same rate as CBO projects for 2026 (3.8 percent). For ways to cut Social Security, see here.