Via the Washington Examiner. For more about how the Jones Act has encouraged imports of Russian energy, please see this blog post or visit the Cato Institute’s Jones Act webpage.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Trade Policy

U.S. Protectionism Gives Boost to Russian Energy Imports

As outrage mounts over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Americans may be chagrined to learn that despite being the world’s largest oil producer and a net exporter of petroleum products, the United States turns to Russia to help meet its energy needs. Indeed, imports of Russian petroleum products have averaged over 370,000 barrels per day over the last decade, and in 2020 Russia was the third-largest source of U.S. petroleum imports. But why? While a number of factors explain this phenomenon, part of the answer lies in protectionist U.S. policy. More specifically, the Jones Act.

Passed in 1920, the Jones Act restricts the domestic waterborne transport of goods to vessels that are U.S.-flagged, U.S.-built and mostly U.S.-crewed and owned. But such vessels are several times more expensive to build and operate than foreign ships, resulting in very high shipping rates. So high, in fact, that after factoring in the cost of Jones Act shipping it can often make more sense to buy products from distant countries rather than other parts of the United States—including petroleum.

An explainer about the importation of Russian oil and petroleum released last week by the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), for example, strongly hints at the role of expensive domestic waterborne transport.

U.S. West Coast refineries rely on imports of light sweet crude oil from other countries, including Russia, because access to U.S. produced light sweet crude oil is challenged by geography, transportation and logistics [emphasis added],” AFPM states. The blunt the impact of U.S. reliance on Russian imports, the group adds that policymakers can “provide relief from…policies that make it uneconomic to transport crude oil and petroleum products domestically.

A December 2021 statement from AFPM was more explicit about the Jones Act’s impact on sourcing decisions. Noting that half of California’s crude oil needs are secured internationally, AFPM’s Chief Industry Analyst Susan Grissom blamed the state’s inability to secure domestic supplies on “a lack of pipeline and rail transportation options and cost-prohibitive Jones Act shipping requirements.”

Other sources also confirm the 1920 law’s distortionary role. A 2019 Reuters story, for example, highlighted a California refinery’s importation of crude oil from Nigeria instead of other parts of the United States at least partly due to the Jones Act while a 2017 report from the California Energy Commission noted that it cost 67 percent more to ship gasoline to California from the Gulf Coast than Singapore owing to the cost of Jones Act vessels and Panama Canal fees.

A 2017 Financial Times story, meanwhile, cited the Jones Act as a leading reason why East Coast refineries import foreign crude rather than turning to domestic suppliers.

When it’s cheaper for Americans to import oil and gasoline from abroad than other parts of the United States, no one should be surprised when that’s exactly what they do.

But sometimes the purchase of American energy isn’t just more expensive because of the Jones Act, but flat-out impossible. Despite a domestic abundance, liquefied natural gas (LNG) cannot be transported within the United States by water owing to a complete lack of LNG tankers compliant with the law (perhaps no surprise given that building such a vessel in the United States is estimated to cost over $500 million more than one constructed abroad). Instead, regions of the United States reliant on LNG tankers to meet their energy needs—New England and Puerto Rico—must source their natural gas from abroad. While such purchases are mostly from Trinidad and Tobago, recent years have seen cargoes that originated in Russia.

And so it is that a law justified on national security grounds encourages the purchase of foreign, including Russian, energy supplies over those produced within the United States.

In recent days there has been an understandable desire to punish Russia through sanctions. But changes to the Jones Act or even temporary waivers allowed for reasons of national defense should also be firmly on the table. Revisiting the law offers a unique two-fer that could both disincentivize the purchase of Russian energy products while offering a needed boost to the U.S. economy at a moment of increasing uncertainty.

Related Tags

Protectionist Buy America Requirements Undermine Biden Administration’s Infrastructure Goals

Last November President Biden signed into law the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), a $1.2 trillion bill that the White House claims will produce benefits ranging from clean drinking water to enhanced broadband. What’s quickly becoming apparent, however, is that the IIJA’s ability to deliver such improvements is being undermined by protectionist measures included in the legislation.

Buried within the IIJA—on page 866 of the 1,039-page bill—is the Build America, Buy America Act (BABA) which, as the name implies, imposes protectionist “Buy America” mandates requiring the use of U.S.-made products and materials. While such requirements have long been a costly feature of federal infrastructure spending, the BABA significantly increases their bite. Traditionally limited to transportation and water-related projects, the BABA expands the spectrum of public works subject to such protectionism to include projects such as dams, buildings, and electrical transmission facilities.

And it’s not just the scope of projects that has been expanded, but the types of construction materials as well. Limited in the past to iron and steel, the IIJA’s Buy America requirements now include nonferrous metals (e.g., copper), plastic- and polymer-based products, glass (including optic glass), composite building materials, lumber, and drywall. The legislation also requires manufactured goods purchased with IIJA funding to be produced in the United States and have at least 55 percent U.S. content.

As a variety of industries are pointing out, however, such requirements introduce considerable obstacles to the improvement of domestic infrastructure. Which is supposed to be why the IIJA was passed.

In a January 31 letter to Biden Administration officials, for example, several telecom groups noted that the 55 percent U.S. content requirement does not comport with industry realities where complex global supply chains are common. “While a few individual network elements might meet the 55 percent domestic content threshold they are extremely limited in number, and it appears that no combination of network products would meet the IIJA’s content requirements from end-to-end,” the letter stated.

Such domestic content requirements may mean a big payday for individual firms like Corning, but the overall effect will be delays and increased costs. That’s true not only for efforts to improve broadband networks but all manner of public works projects that rely on communications technologies to boost automation and efficiencies.

But the cost of Buy America requirements isn’t just about higher expenses and extended timelines, but quality as well. As firms in the water sector have pointed out in their own letters to members of the administration, such requirements call into question the industry’s ability to secure the best available technologies for the systems they use. That has implications not only for public health and the provision of clean drinking water, the industry argues, but the environment given the need for technologies that ensure maximum efficiency and the reduction of carbon emissions.

It’s also an additional headache at a time when securing needed components and systems is already a struggle amidst strained supply chains.

Beyond the telecom and water sectors, meanwhile, state transportation officials are cautioning that Buy America requirements could hamper efforts to deploy 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations. A letter to the Department of Transportation from five states cited “concern that states will not be able to locate sufficient, if any, [electric vehicle] charging equipment that complies with Buy America requirements” while New Jersey state officials warned that if Buy America requirements are extended to Make-Ready components (parts such as wiring used in charging stations) that it would “create an incredibly complex challenge for both states and utilities to meet or even attempt to verify.”

To address these added costs and complications both industry and state officials have called for waivers from Buy America requirements. Such waivers can be secured if products and materials are not domestically available in sufficient quantities and/or of satisfactory quality, if the use of domestic products/materials raise a project’s overall cost by more than 25 percent, or if Buy America requirements can be shown to be inconsistent with the public interest.

Administration officials, however, don’t exactly appear to be champing at the bit to grant them.

Questioned about waivers for the telecom sector last week, the head of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration said that “There has to be a high bar, and we have to be very smart and very tailored about any waivers that we give.”

Even if agency heads agree on the need for waivers, they may face a rocky path to securing them. Whereas previously the agencies that administered Buy America requirements were responsible for considering waiver requests, in January 2021 the Biden administration required that waivers pass muster with the Office of Management and Budget’s Made in America Office (MIAO). With the MIAO tasked with “increase[ing] reliance on domestic supply chains and reduc[ing] the need for waivers”, requests for relief from Buy America requirements might not face the most receptive audience.

And as the telecom industry points out in another letter, just the process alone of reviewing each and every waiver request to purchase a piece of equipment could produce significant delays.

Is this how America builds back better?

If it accomplishes nothing else, the IIJA offers a cautionary tale about the counterproductive nature of Buy America rules. Such restrictions introduce complications, delays, added costs, and are at odds with carefully built globalized supply chains designed to ensure maximum efficiency. They limit the government’s ability to secure the highest quality product at the best price. More fundamentally, they undermine the IIJA’s primary purpose of rebuilding infrastructure.

The Biden administration has made the improvement of U.S. infrastructure a centerpiece of its domestic agenda. Buy America requirements are an obstacle to the achievement of that goal. Let’s hope that waivers are generously and quickly issued to help mitigate the impact of this ill-advised and counterproductive policy.

Related Tags

A Valentine’s Day Full of Chocolate, Roses, and… Tariffs?

Chocolate and roses are the language of love, and through them, millions of people in the United States will today express their affection for their significant others. Yet, for the — *ahem* — dispassionate analysis we conduct here at the Cato Institute, candy and flowers are also prime examples of how free trade improves our lives by making it easier to purchase quality goods at lower prices, and by contrast, how protectionism does just the opposite.

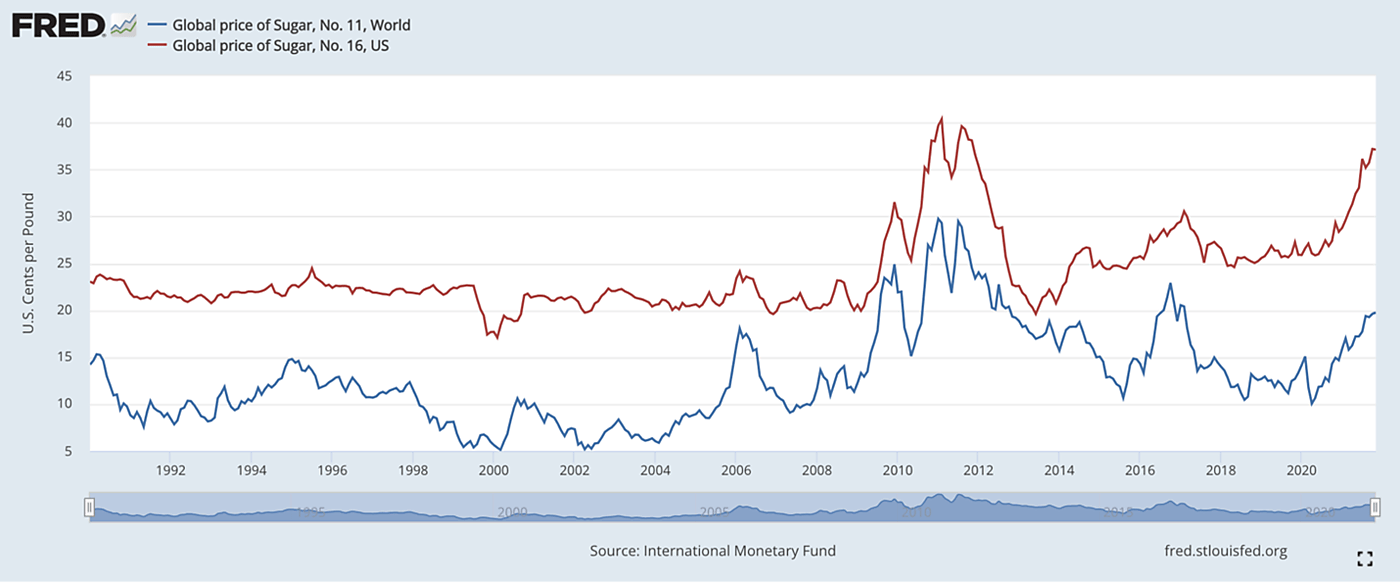

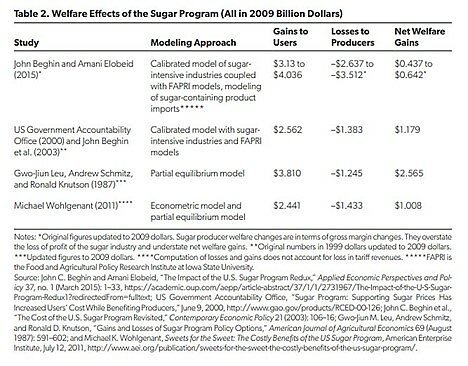

In the case of chocolate, we have previously explained how the U.S. sugar program – a complex array of government price supports and import restrictions – dramatically increases U.S. prices of not only sugar, but also for chocolate, other sweets, and anything else that requires significant amounts of sugar. Today, U.S. consumers pay as much as three times the world market price for sugar, and this in turn raises the price of sugary products like the chocolates gifted on Valentine’s Day.

High sugar prices harm not only consumers, but domestic food manufacturers (such as candymakers) and their workers too. The sugar program results in the annual loss of an estimated 20,000 jobs in U.S. food processing industries, and many companies have left the country to avoid a massive tax on one of their main ingredients. For instance, chocolate-producing firms like Ferrero, Nestlé SA, Tootsie Roll Industries Inc., Mondelez International Inc., and Mars Inc. have set up operations in Canada to benefit from low sugar costs and thereby have a competitive advantage in the U.S. market. Altogether, eliminating the sugar program would generate as much as $5.24 billion dollars (in today’s dollars) in annual benefits for users.

As Lincicome also notes, moreover, the costs of the U.S. sugar program are not just limited to higher prices. They also include: Health costs (from increased American consumption of high fructose corn syrup, which many manufacturers use instead of sugar because it’s cheaper here); Foreign policy costs (as U.S. sugar protectionism stunts economic development in poorer neighboring countries that have climates and workforces more suited for cane sugar production, and pushes some to turn to cultivating illegal narcotics and violence); Environmental costs (from sugar cane farms’ air and water pollution); Other trade costs (such as worse terms on non‐sugar issues in U.S. trade deals); and political costs (including millions of dollars paid in lobbying and in campaign contributions to Republican and Democratic legislators so they’ll resist reforms).

Roses, on the other hand, highlight the benefits that free trade has brought to millions of people in America. Trade expert Sarah Smiley notes that, until the late 1980s, most roses sold in the United States were grown in California, and a dozen of them would cost around $150. Today, the same amount of roses can cost as little as $10. Driving this change is tariff liberalization: Today, most roses consumed in the United States are imported, and approximately 64% of the $553 million in rose imports in 2020 came from Colombia and 32% come from Ecuador. After years of restricting these imports (via various tariffs, including trade remedies) in the 1980s and 1990s, trade in most flowers was liberalized through bilateral trade agreements (e.g., the US-Colombia FTA) and unilateral preference programs for developing countries (the Andean Trade Preferences Act and, later, the Generalized System of Preferences).

Roses from Ecuador were actually excluded from GSP until November 2020, but Congress a month later let GSP expire, thus forcing U.S. importers (and, eventually, consumers) of Ecuadorean roses to pay the statutory tariff rate of 6.8 percent on these goods. According to the Coalition for GSP, this means that “Ecuadorian roses faced up to $18 million in tariffs in 2021,” and that — given the large number of roses imported from Ecuador into the United States each year – the expiration of GSP and the ensuing 6.8 tariff rate “has the same effect as adding 2.5% to the cost of all imports.” The Coalition adds that, because U.S. consumers in 2021 liked Ecuadorean roses too much (causing import volumes to surpass GSP’s “competitive need limitation” ceiling, above which imports lose preferential tariff treatment), even if Congress were to renew GSP without reforming the system, Ecuadorean roses would remain subject to a 6.8 tariff – harming American businesses and consumers in the process.

So, as you treat your significant other today to a nice bouquet of roses or a delicious box of chocolates, remember that trade has made such a tradition more accessible than before—and freer trade could make it even more accessible in the future.

If Congress had a heart, that is.

Related Tags

5 Years Later the United States Is Still Paying for Its TPP Blunder

Last month—January 23 to be exact—marked the five-year anniversary of President Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. The country has been paying for it ever since.

Comprised of the United States and eleven other Pacific Rim countries—including economic heavyweight Japan—the TPP was found by a 2016 Cato analysis to result in net trade liberalization. A study by the U.S. International Trade Commission calculated a real U.S. GDP increase of $42.7 billion through 2032 as a result of TPP membership while a Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) working paper foresaw gains to U.S. real incomes of $131 billion through 2030.

But the United States withdrew from the TPP, and those gains never happened.

The TPP, however, was aimed at more than just lowering trade barriers. It was also an attempt by the United States—along with like-minded allies—to help shape the rules governing trade in the Asia-Pacific region. As Asia’s center both geographically and economically, China is already assured of having a significant say in such matters. The TPP was meant to ensure the United States had a prominent seat at the table when such rules were being hammered out—before it opted to push away.

In other words, U.S. losses from its TPP withdrawal have not just been economic but geopolitical. And if the TPP was deemed a useful tool in countering China’s influence during the years it was being negotiated, it would be even more of an asset now given the bilateral relationship’s increasingly acrimonious nature.

Other countries have been less short-sighted in their trade policies. Following U.S. withdrawal, the remaining TPP members went back to the negotiating table and struck a new deal: the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). As a result, these countries often have easier access to each other’s markets than what Americans enjoy. That’s a boon to consumers and businesses in CPTPP members who enjoy cheaper imports and expanded export opportunities.

Indeed, the CPTPP has proved so alluring that China and Taiwan have both applied to join while South Korea has taken initial steps toward becoming a member. Even the United Kingdom wants in.

Other notable trade liberalization initiatives have taken place in recent years as well. In late 2020, 15 countries of the Asia-Pacific region concluded the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Entering into force on January 1 of this year, the RCEP—which notably includes China—contains tariff reductions and regulatory harmonization measures meant to spur trade between member countries. And in 2018, Japan and the European Union signed a trade deal that took effect the following year.

Amidst such trade integration, the United States has largely been left on the outside looking in. This means that not only has the country foregone the TPP’s projected benefits but the competitiveness of U.S. firms has been eroded owing to the lack of preferential market access enjoyed by their foreign counterparts.

As a result, a 2017 PIIE analysis calculated that the TPP/CPTPP’s net impact on the United States had swung from a $131 billion gain to a $2 billion loss. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, meanwhile, found that RCEP will shrink U.S. exports by over $5 billion as trade is diverted away from U.S. firms and toward foreign competitors subject to lower tariff rates under the agreement.

Even U.S. leaders have implicitly recognized that U.S. withdrawal from the TPP placed the United States on the backfoot in trade. In 2019, President Trump concluded a limited “mini-deal” with Japan to claw back some of the lost gains from TPP withdrawal. Presented as the prelude to a more comprehensive agreement (which never happened), the market access improvements realized from the agreement—mostly on agriculture and industrial goods—were still inferior to what would have been gained via the TPP.

Art of the deal, indeed.

On the geopolitical front, meanwhile, a recent Wall Street Journal piece points out that U.S. inaction on trade liberalization has handed a possible opportunity to China:

Beijing’s pro-trade steps have fueled concerns among American businesses and close allies. They worry that the U.S.’s absence in regional trade agreements gives Beijing an opening to establish its leadership in setting rules and standards for trade and economy, particularly in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and digital trade.

In a bid to reassert U.S. economic leadership the Biden administration is readying a new initiative called the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Although its exact contours are unknown, all indications are that it will not include improved market access measures such as tariff reductions. That means the United States will be competing for influence with China with one hand effectively tied behind its back. While Beijing offers improved access to its vast market through its participation in RCEP—and possibly the CPTPP—Washington will have few obvious enticements with which to sway other countries toward adopting its preferred set of trading rules and standards.

All of this could have been avoided. Had the United States remained in the TPP and Congress approved the deal, American consumers and businesses would be enjoying cheaper imports and expanded exports while U.S. diplomats would be better positioned to set trade rules in the Asia-Pacific region. Instead, all Washington has to show for its efforts is a less than comprehensive trade deal with Japan and a new economic initiative whose allure for U.S. trading partners is unclear. Rather than pursuing such half measures, the United States should return to the TPP/CPTPP. That, however, will require both vision and leadership, two commodities that are unfortunately currently lacking in Washington.

Related Tags

Dumping on American Builders and Homebuyers

As we at Cato frequently explain, “trade remedies” tariffs — antidumping, countervailing duty, and safeguard actions — are one of U.S. trade policy’s dirty little secrets. They’re insanely (and intentionally) complex, buried in layers of regulatory mumbo-jumbo, and thus mostly ignored by politicians, media, and laypeople who often claim or believe that the United States is some sort of bastion of “unfettered free trade” (or whatever). Yet trade remedy measures here are numerous — there are 659 AD/CVD orders in place today (almost doubling since 2016) — and constitute significant, long-lasting restrictions on imports of essential goods into the United States. By raising the domestic prices of hundreds of products that American companies and consumers need, trade remedies impose significant harms on the U.S. economy — harms that go unnoticed by the general public, except in rare circumstances.

Among those circumstances is when trade remedy measures happen to affect a product or issue that Americans, and the American media, care deeply about. With that in mind, Cato last year commissioned a paper from academic economists Alessandro Barattieri and Matteo Cacciatore to examine how U.S. trade remedy measures on key construction materials — inputs used by American companies to build homes, office buildings, and everything in between — affect the prices of those materials and, by extension, how U.S. trade policy likely affects prices of new homes in the United States. The new paper would build on their excellent work in a 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research paper showing how trade remedies affect imports of industrial inputs and the U.S. manufacturers that consume them. (You can read my short review of the paper here.)

The economists’ latest results, published today in a new Cato Briefing Paper (“American Protectionism and Construction Materials Costs”), are striking and have significant implications for U.S. trade, construction, and housing policy. After first noting the substantial recent increase in both U.S. construction materials prices and home prices (see Figure 1 below), they gather data on the most significant U.S. trade remedy measures affecting the domestic construction materials sector.

These data are summarized in Table 1 below, which shows the most important industries receiving trade remedies protection among the construction sector’s material suppliers; the share of imports subject to new trade remedies measures; and the level of duties applied to subject imports. The eight industries listed in column 1 account for approximately 25 percent of the U.S. construction sector’s intermediate inputs, and, as you can see in column 3, applied duty rates in these cases are substantial (ranging from 28 to 134 percent). Unsurprisingly, largest share of imports covered by U.S. trade remedy measures is in the “sawmills and wood preservation” industry (almost 82 percent of all imports — see columns 4 and 5), which is surely driven by the current duties on Canadian lumber. However, the data also show that (as I’ve covered previously) U.S. trade remedy measures cover all sorts of other products — pipes, nails, cabinets, wood flooring, plywood, sinks, shelving units, etc. — that American builders use every day.

Barattieri and Cacciatore next use these data, along with data from the Federal Reserve’s monthly producer price index for construction materials, to determine how the former affect the latter, accounting for other factors potentially affecting the construction sector. They then estimate how much an increase in U.S. trade remedies actions affects construction materials prices in subsequent months, and as shown in Figure 2, find that a U.S. trade remedy action causes domestic construction material prices to increase significantly up to 18 months after the measure’s implementation. In particular, they find that “a uniform 1 percentage point increase in the share of construction material imports into the United States that are subject to new trade remedies (corresponding to a 1.35 percentage point uniform import tariff) increases the domestic price of those materials by 0.9 percent after six months.” They check their results using an alternate dataset — the Federal Reserve’s price index of net inputs to residential construction — and obtain similar results (see Figure 3).

The authors’ conclusions are worth quoting in full:

Tariffs imposed by the U.S. government on materials used by the domestic construction sector cause a significant increase in the cost of those goods. These results suggest that lifting trade restrictions on intermediate inputs could help dampen recent increases in U.S. construction material costs. Addressing the ultimate impact of these trade barriers on skyrocketing U.S. housing prices is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, U.S. homebuilders report that they often pass on higher material costs to homebuyers, and previous research notes that many homes in the United States are priced close to their construction cost, of which materials (e.g., lumber) are a significant part. Our results therefore suggest that U.S. trade barriers affect home prices, at least in certain areas, and that this connection is an important avenue for future analysis and research.

As we’ve often discussed here at Cato, there is no “quick fix” to the U.S. trade remedies system, which is rife with abuse and causes numerous economic, foreign policy, and domestic political problems, yet has been intentionally designed by Congress to ignore consumer or broader national interests. A lasting, legislative solution is therefore required. Hopefully, the findings in this new paper — and others like it — will help to generate new support for such obvious and necessary changes to U.S. law.

You can read the full text of the new paper, including its detailed methodology, here.

Related Tags

This (Steel) Deal Is Getting Worse All the Time

Yesterday, the Biden administration announced an agreement with Japan to lift some of the U.S. “national security” tariffs on Japanese steel products that the Trump administration imposed in 2018 pursuant to Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. As with a similar European deal announced last Fall (see our writeup here) and implemented in January, the U.S.-Japan deal has been lauded as “ending” Trump’s steel tariffs and “mending ties with a major ally,” but a closer examination reveals it to share many, if not more, of the EU agreement’s shortcomings and to continue President Trump’s misguided and ineffectual approach to tariffs, international trade law, and geopolitics.

For starters, the new agreement doesn’t even touch the Section 232 tariffs on aluminum from Japan, nor does it actually eliminate Trump’s steel tariffs. Instead, the deal simply replaces the steel tariffs with a complex “tariff rate quota” (TRQ) system, under which 1.25 million metric tons (MMT) of Japanese steel — applied to 54 different product categories on a first-come, first served quarterly basis (with little period-to-period flexibility) — will be allowed to enter the United States tariff-free. Any Japanese imports above that amount will remain subject to the existing 25%, “national security” tariffs.

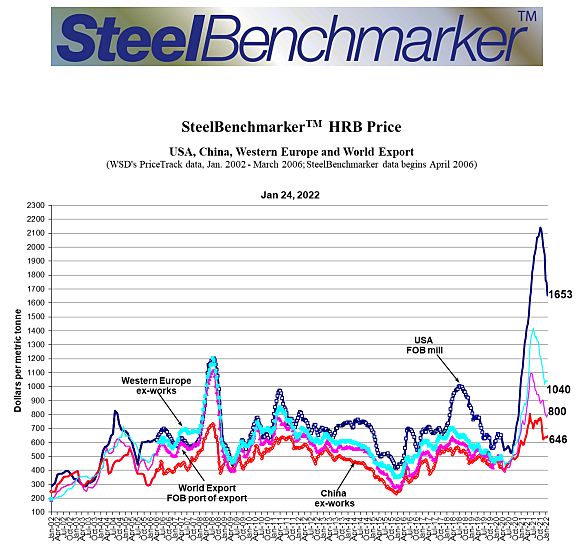

Given the quota amount and design, moreover, it’s quite likely that significant volumes of Japanese steel will still face — and American importers will thus keep paying — U.S. tariffs. Most obviously, the 1.25 MMT quota limit has been set well below pre-tariff volumes and even further below the amounts that would likely enter the U.S. today in the absence of any trade restrictions. According to my former colleagues at the law firm of White & Case, for example, Japanese steel imports “averaged approximately 2.03 MMT during the pre-duty 2015–2017 period” — a period that was experiencing far less industrial demand than today. Thus, the new TRQ level is, at best, set at a paltry 61% of current U.S. market demand and probably much lower than that. As we explained with the EU agreement, the U.S.-Japan deal will therefore keep U.S. steel prices high, leaving steel-consuming American manufacturers at a significant disadvantage versus their global competitors. Indeed, the EU deal has now been in place several weeks, and U.S. hot-rolled steel prices are still far higher than prices in Europe and elsewhere:

White & Case further notes that the Japan agreement is actually more restrictive than the EU deal because it likely will count Japanese steel currently excluded from the Section 232 tariffs against the new TRQ limits. (The EU deal expressly exempted these imports from the TRQs, meaning more duty-free European imports overall.) The tariff-supporting Steel Manufacturers Association naturally celebrated this provision, noting that 550,000 metric tons of steel products — almost half of the new TRQ — entered under an exclusion last year. Once you factor in this already-excluded steel, the Japan deal’s tariff liberalization — and thus its effect on U.S. prices and relief for U.S. manufacturers — becomes even more modest.

The quota’s design, which essentially mirrors the EU agreement, will further limit this tariff relief. As we discussed in November, for example, “TRQs administered in this fashion are sure to introduce distortions, for example, large U.S. importers stockpiling early in a quarter and paying higher prices to do so.” According to the Coalition of American Metal Manufacturers, this very problem has already emerged with the U.S.-EU agreement: “some steel products’ quota filled up for the year in the first two weeks of January,” and so they now worry that the Japan deal will “lead to market manipulations and allow for gaming of the system that puts this country’s smallest manufacturers at an even further disadvantage.” Other concerns with the EU system, such as its “melted and poured” rule for qualifying products, are also present in the new Japan agreement. (Go here for more.)

So, for those who support free markets and the removal of U.S. trade barriers, the Biden administration basically took a bad trade deal and made it even worse.

Finally, the new Japan agreement once again shows the emptiness of the United States’ “national security” justifications for these tariffs — the term isn’t even mentioned in the official documentation — and of the Biden campaign’s promise to improve U.S. foreign policy and heal Trump-era tensions with major allies. As has been widely reported, the Japanese government sought the Section 232 tariffs’ complete removal, which President Biden could achieve with the stroke of a pen. They still don’t seem to be thrilled with this deal, but apparently figure that a little liberalization — and some sweet quota rents for Japanese steelmakers — is better than nothing. If fixing obvious and absurd Trump-era wrongs to critical regional allies were really more important to the White House than placating U.S. steel companies and unions, the president would have removed the tariffs entirely. He didn’t.

So much for national security.