Chocolate and roses are the language of love, and through them, millions of people in the United States will today express their affection for their significant others. Yet, for the — *ahem* — dispassionate analysis we conduct here at the Cato Institute, candy and flowers are also prime examples of how free trade improves our lives by making it easier to purchase quality goods at lower prices, and by contrast, how protectionism does just the opposite.

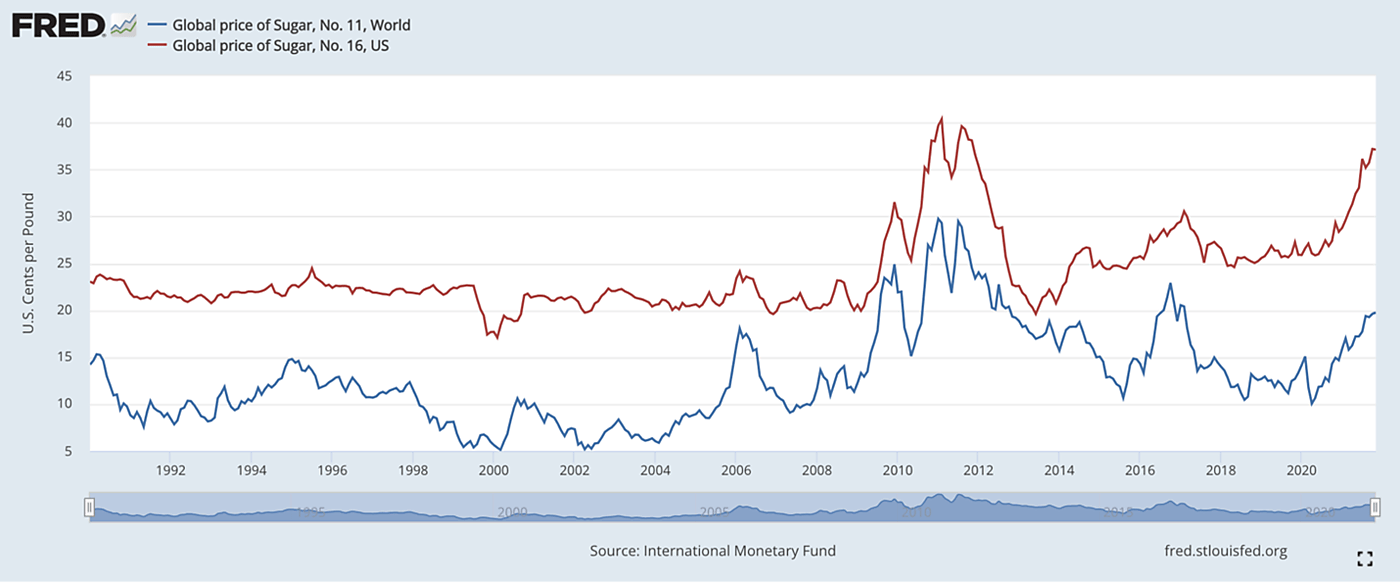

In the case of chocolate, we have previously explained how the U.S. sugar program – a complex array of government price supports and import restrictions – dramatically increases U.S. prices of not only sugar, but also for chocolate, other sweets, and anything else that requires significant amounts of sugar. Today, U.S. consumers pay as much as three times the world market price for sugar, and this in turn raises the price of sugary products like the chocolates gifted on Valentine’s Day.

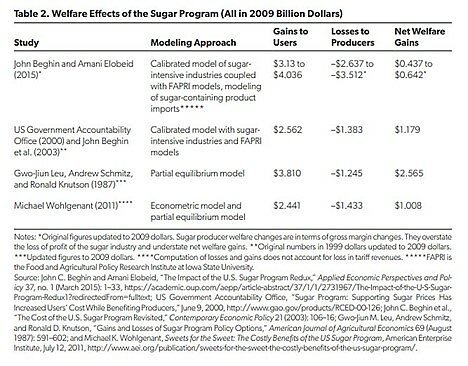

High sugar prices harm not only consumers, but domestic food manufacturers (such as candymakers) and their workers too. The sugar program results in the annual loss of an estimated 20,000 jobs in U.S. food processing industries, and many companies have left the country to avoid a massive tax on one of their main ingredients. For instance, chocolate-producing firms like Ferrero, Nestlé SA, Tootsie Roll Industries Inc., Mondelez International Inc., and Mars Inc. have set up operations in Canada to benefit from low sugar costs and thereby have a competitive advantage in the U.S. market. Altogether, eliminating the sugar program would generate as much as $5.24 billion dollars (in today’s dollars) in annual benefits for users.

As Lincicome also notes, moreover, the costs of the U.S. sugar program are not just limited to higher prices. They also include: Health costs (from increased American consumption of high fructose corn syrup, which many manufacturers use instead of sugar because it’s cheaper here); Foreign policy costs (as U.S. sugar protectionism stunts economic development in poorer neighboring countries that have climates and workforces more suited for cane sugar production, and pushes some to turn to cultivating illegal narcotics and violence); Environmental costs (from sugar cane farms’ air and water pollution); Other trade costs (such as worse terms on non‐sugar issues in U.S. trade deals); and political costs (including millions of dollars paid in lobbying and in campaign contributions to Republican and Democratic legislators so they’ll resist reforms).

Roses, on the other hand, highlight the benefits that free trade has brought to millions of people in America. Trade expert Sarah Smiley notes that, until the late 1980s, most roses sold in the United States were grown in California, and a dozen of them would cost around $150. Today, the same amount of roses can cost as little as $10. Driving this change is tariff liberalization: Today, most roses consumed in the United States are imported, and approximately 64% of the $553 million in rose imports in 2020 came from Colombia and 32% come from Ecuador. After years of restricting these imports (via various tariffs, including trade remedies) in the 1980s and 1990s, trade in most flowers was liberalized through bilateral trade agreements (e.g., the US-Colombia FTA) and unilateral preference programs for developing countries (the Andean Trade Preferences Act and, later, the Generalized System of Preferences).

Roses from Ecuador were actually excluded from GSP until November 2020, but Congress a month later let GSP expire, thus forcing U.S. importers (and, eventually, consumers) of Ecuadorean roses to pay the statutory tariff rate of 6.8 percent on these goods. According to the Coalition for GSP, this means that “Ecuadorian roses faced up to $18 million in tariffs in 2021,” and that — given the large number of roses imported from Ecuador into the United States each year – the expiration of GSP and the ensuing 6.8 tariff rate “has the same effect as adding 2.5% to the cost of all imports.” The Coalition adds that, because U.S. consumers in 2021 liked Ecuadorean roses too much (causing import volumes to surpass GSP’s “competitive need limitation” ceiling, above which imports lose preferential tariff treatment), even if Congress were to renew GSP without reforming the system, Ecuadorean roses would remain subject to a 6.8 tariff – harming American businesses and consumers in the process.

So, as you treat your significant other today to a nice bouquet of roses or a delicious box of chocolates, remember that trade has made such a tradition more accessible than before—and freer trade could make it even more accessible in the future.

If Congress had a heart, that is.