In a Cato study last year, I argued that the U.S. policy of maintaining hundreds of permanent forward-deployed military bases around the world is not only unnecessary, but also actually counterproductive in some ways. Advocates of forward-deployment claim it pacifies the international system by deterring adversaries and reassuring allies, thus ameliorating conflict spirals and staving off interstate wars.

I argued instead that today’s lower rates of interstate conflict are a result of many factors – including defense dominance, economic interdependence, changing norms, etc. – other than forward basing and the security guarantees that underlie them. I further claimed that forward bases can actually undermine peace and stability by incentivizing “reckless driving” by allies and counterbalancing by adversaries. This is a view deeply at odds with the prevailing opinion in the Washington, DC foreign policy establishment.

Yet a new study from the RAND Corporation bears some of my analysis out. RAND researchers developed a statistical model to see how U.S. overseas bases correlated with interstate conflict. Though they find that “on average, U.S. troop presence was associated with…a lower likelihood of interstate war,” they concede their model can’t determine causation and can’t account for the impact that other factors (mentioned above) have had on the reduction of interstate conflict in the post-WWII period.

And while the study suggests there is good evidence for the restraining effect that U.S. bases have on allies (see here for a study suggesting otherwise), it also finds that stationing U.S. troops and bases overseas is “associated with a higher likelihood of low-intensity interstate conflict” and that “a large nearby U.S. troop presence was associated with potential U.S. adversaries initiating more low- and high-intensity conflicts.”

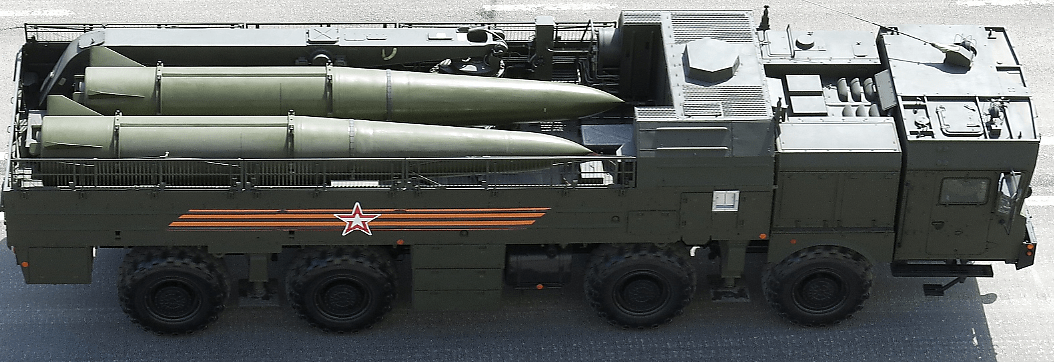

“Adversary states,” according to RAND, “are more likely to initiate a high-intensity MID [militarized interstate dispute] against a target state when the United States maintains a large troop presence in that target state. This suggests that adversaries may be threatened by U.S. forward presence abroad, leading to an increased risk of militarized behavior.”

For example, the authors of the study argue that U.S. basing in the Baltic states may deter Russia from initiating major war against them, “but also may lead to the initiation of more disputes and provocations [short of all-out war] by Russia against the Baltic states.” Similarly, U.S. military presence in and near the South China Sea may play a role in deterring China from outright attacking neighboring states with competing maritime and territorial claims, but also “may lead to the intensification of Chinese militarized activities and provocations toward the partner states that host U.S. forces.” Another example is the Korean Peninsula. “U.S. troop presence has likely deterred North Korean aggression against South Korea,” the RAND study concludes, “but it has potentially done so at the cost of numerous militarized activities and provocations by North Korea during many decades.”

This should not be construed to mean that, in the absence of U.S. bases or security guarantees, Russia would conquer the Baltic states, or China would attack the Philippines, or North Korea would initiate war with South Korea. Each of these adversaries has good reasons — other than the threat of a U.S. response — not to take such action.

Here is the real kicker. Another argument in my own Cato study was that having all these bases and troops permanently stationed abroad has the effect of expanding the scope of perceived U.S. interests, thus increasing U.S. military interventionism abroad. The RAND study concurs:

Some analysts contend that U.S. involvement abroad actually leads to an expansion of U.S. security concerns and issues over which it is willing to use force. Frequent diplomatic interactions can lead to socialization, where the U.S. leaders adopt partners’ local security concerns. Moreover, once the United States makes a commitment to a partner, U.S. policymakers may also begin to see U.S. credibility at stake in any of the partner’s disputes. The United States may, in turn, be more likely to initiate or become involved in militarized conflicts to protect these interests. U.S. forward troop presence may contribute to the expansion of these concerns. U.S. military presence in partner states creates more opportunities for socialization, described above, and further ties U.S. reputation to its partners’ security. Moreover, forward presence may make the United States more sensitive to the capabilities and intentions of nearby states that could pose a physical threat to local U.S. personnel or infrastructure. The need to defend forward deployments and support regional partners may expand the domain of issues in which the United States is willing to use force, thereby increasing the risk that the United States initiates conflict abroad.

That’s an important finding. U.S. military activism has indeed spiked in the post-Cold War era, though we’re not better off for it. If forward-deployment pushes the United States to use military force with greater frequency and in more locations for what would otherwise be peripheral interests, that should be deeply concerning to Americans.