Trump’s threat to “totally destroy North Korea” at the United Nations this week generated concern in many corners but a round of applause from many hawks here in the United States. Former ambassador to the United Nations John Bolton, for example, called it “the best speech of the Trump Presidency,” praising Trump for his tougher approach to North Korea’s nuclear program. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also voiced strong support for Trump’s approach. In a New York Times oped, Abe wrote that, “I firmly support the United States position that all options are on the table.”

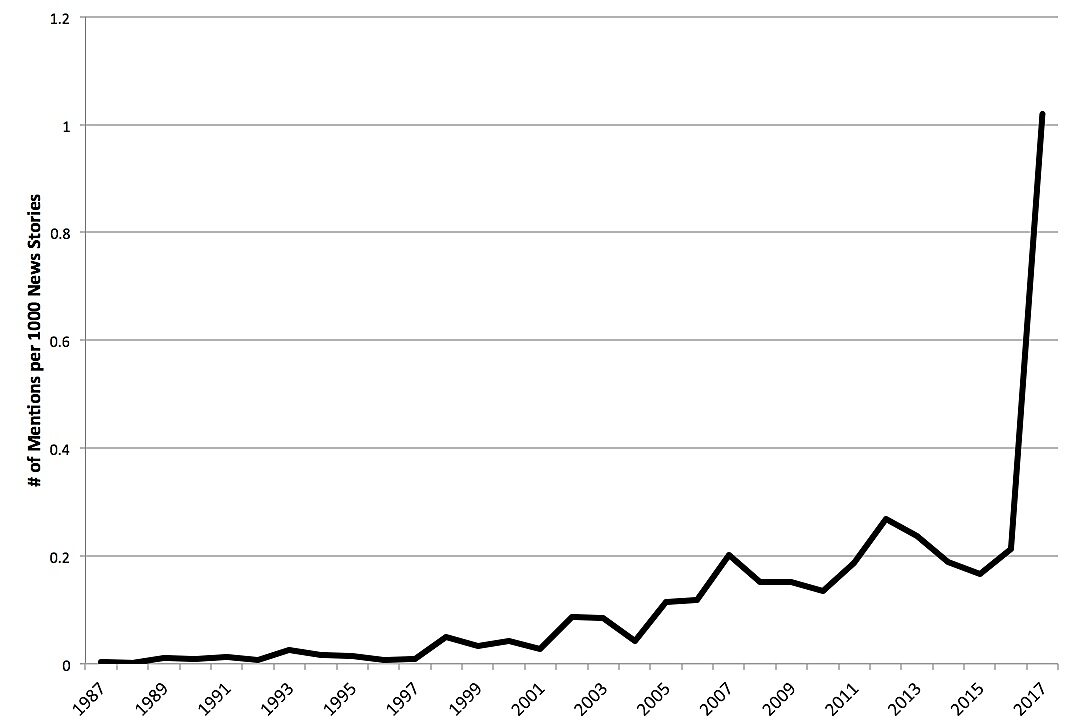

Abe’s choice of the phrase “all options are on the table” was not accidental. As Figure one indicates, the phrase has steadily gained in popularity since the September 11 attacks, with its use spiking in the first year of the Trump administration, as tensions with North Korea have risen.

Figure One: The Rise of “All Options on the Table”

Data source: Factiva Top U.S. newspapers database.

The meaning of the phrase, at least on paper, is clear: the United States is willing to use military force should diplomacy fail. And as tensions rise, as they have over the past months with North Korea, one would expect to hear the phrase more often.

The problem, however, is that despite occasional protests to the contrary, it is increasingly obvious that the Trump administration is ready to take the most important option off the table: diplomacy. By repeatedly arguing that, “talking is not the answer,” and that “we’re out of time” to deal with North Korea’s nuclear program, the administration is raising the stakes of the crisis and the chances that it ends in a military conflict.

No matter how happy that makes the hawks, conflict with a nuclear and well-armed North Korea would be both a military disaster and out of touch with the desires of the American public. In survey after survey over the years, Americans have voiced greater confidence in diplomacy than military strength as the best path to peace.

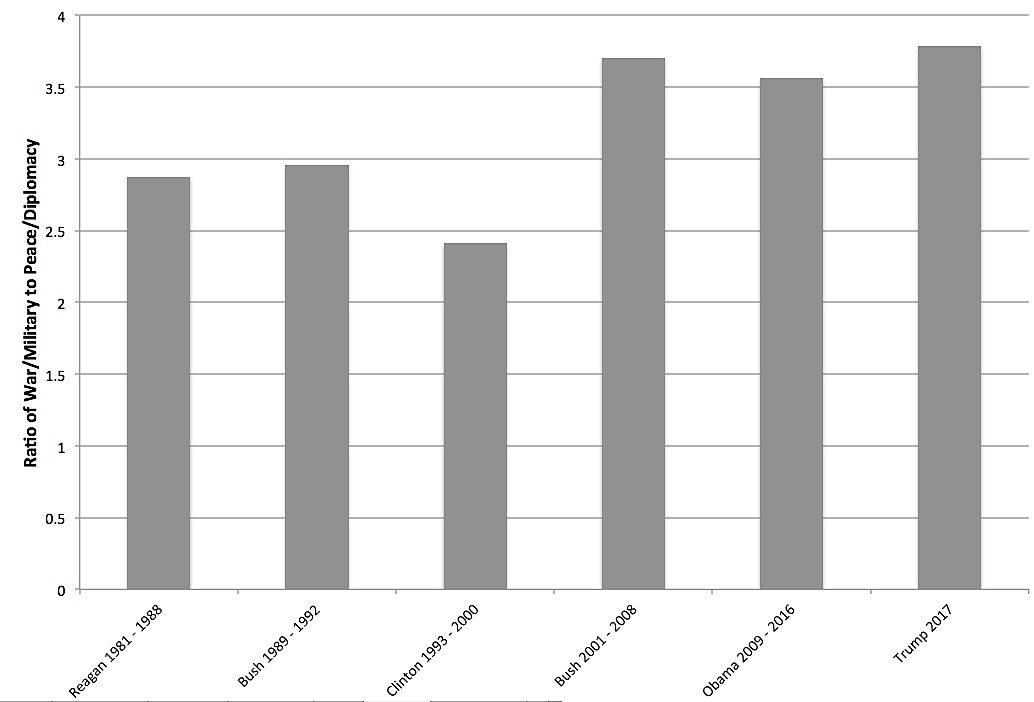

For those with concerns about Trump’s language, it is important to note that although Trump’s bellicose style is very different from that of his predecessors, he is not much more hawkish than either George Bush or Barack Obama. As Figure Two shows, the three post‑9/11 presidents all have had “hawk indexes” higher than the three previous presidents.

The hawk index is the ratio of how often a president appears in news stories that mention the words “war” or “military” compared to how often he appears in stories that mention the words “peace” or “diplomacy.” The score reflects not only the state of the international arena the president is coping with, but also the relative frequency that he discusses military options compared to diplomatic ones. As Figure Two reveals, American discourse and news coverage has always focused far more heavily on war than peace.

Figure Two: The Hawk Index from Reagan to Trump

Data source: Factiva Top U.S. newspapers database.

Given this data, Trump’s tough talk at the United Nations should come as little surprise. Nor, given the American track record of almost non-stop military intervention since the end of the Cold War, should we be surprised if “all options on the table” actually turns out to mean: “we are about to fight another war.”