Russian aggression in Eastern Europe during the last year has brought to the fore many of the issues surrounding the transatlantic security relationship, in particular, the role of NATO. Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has been floundering, seeking new missions and goals, with recent involvement in military campaigns in Afghanistan and Libya emblematic of this search. In some ways, Russia’s recent actions have brought back a sense of purpose to the alliance.

Unfortunately, NATO still has many problems. Common vision among members is lacking, a problem exacerbated by the expansion of NATO from sixteen members at the end of the Cold War to twenty-eight members today. Many of these new member states in Central and Eastern Europe feel – understandably – more threatened by Russian aggression than West European or North American member states, creating tension within the organization.

NATO itself has increasingly become a political entity. Indeed, the growth of NATO membership among East European states during the last decade has been a key impediment to improved relations with Russia. The suggestion that Georgia and Ukraine might become EU or NATO members has also been widely discussed as one of the roots of the current conflict.

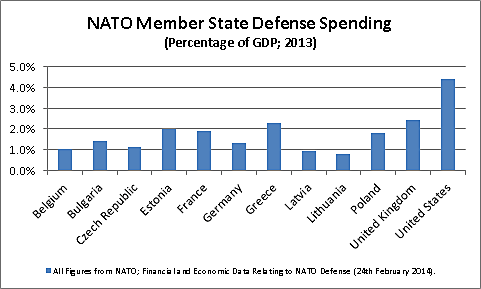

NATO funding is a big problem. Though most member states hail NATO’s importance and demand its services, few are willing to pay the costs, which fall disproportionately on the United States. In 2012–2013, only three other member states met NATO’s stated military spending target of 2% of GDP: the United Kingdom, Estonia and Greece. Many countries which rely heavily on NATO nonetheless contribute little to the alliance or their own defense, relying instead on the United States.

These problems are not new, but current events highlight the need for a more coherent and participatory transatlantic security framework. Is NATO the right tool for the task? Should the alliance be reformed? How should NATO interact with the European Union? And what role should the United States play in European security?

These questions will be discussed at an upcoming Cato policy forum, “The Future of NATO and the Transatlantic Security Framework.” The event features James Goldgeier, Dean of American University’s School of International Service, and author of the 2010 Council on Foreign Relations report The Future of NATO; Cato’s Doug Bandow, a noted critic of NATO, whose recent writings on NATO can be found here and here; and François Rivasseau, Deputy Head of Delegation for the European Union, who has spent his diplomatic career working on European security issues.

The event begins at noon on March 4, 2015. You can learn more, and register for the event here.