In response to the crisis, Congress and the Federal Reserve have provided cities and states with hundreds of billions of dollars in aid. But there are calls for more from the Fed chief, lobby groups such as the National League of Cities, and Democrats and some Republicans on Capitol Hill.

News articles are whipping up fears of an apocalypse unless Congress passes another state-local aid package. Politico claims that states and cities are “slashing” services with “severe” cuts, while Education Week worries about “draconian” cuts to schools. The New York Times says that the virus is “ravaging” state budgets, while Bloomberg worries about California’s looming “budget disaster.”

Such scare stories were common during the Great Recession a decade ago. But we can look back and see that the overall budget adjustments at the time were not that severe, particularly for local governments, which I examine here.

A recent study by the Council of Foreign Relations in support of more state-local aid gets the history wrong with regard to local governments: “The deep economic recession of December 2007 to June 2009 and slow recovery put many subnational budgets in unusually dire straits … The situation was particularly bleak at the local level, where many balance sheets were battered by the collapse of home values and property tax revenues.”

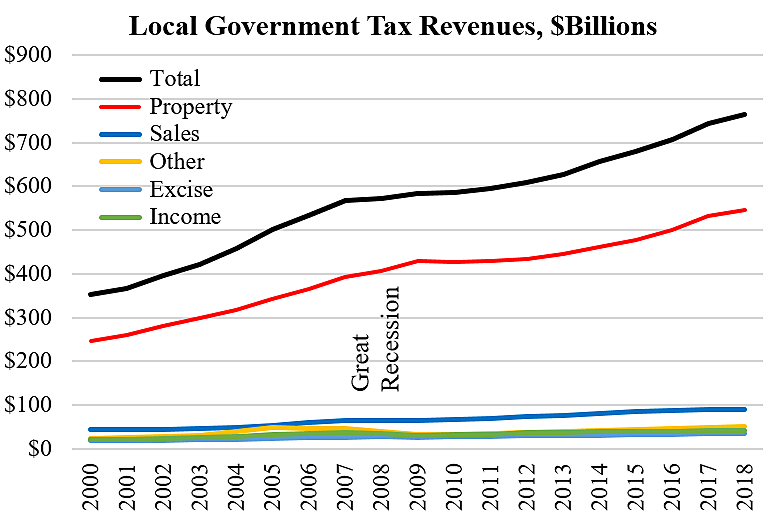

In fact, nationwide local tax revenues did not fall during the Great Recession, as BEA data from Table 3.21 shows in the chart. Property tax revenues—which account for about 72 percent of local tax revenues—remained robust. Revenues rose during the 2000s, flat-lined for a few years during the recession, then started growing again. Even though nationwide home prices dropped more than 20 percent from 2007 to 2011, local governments are slow to adjust valuations which smooths property tax revenues over time.

We will likely see a similar pattern this time. Housing prices do not appear to be falling much, so property tax revenues should remain steady. Zillow expects housing prices to fall 2 percent this year, while Realtor.com expects they will rise 1 percent.

However, prices may decline substantially for commercial properties in some areas, thus suppressing property tax revenues for some governments. And some big cities such as New York may face deep financial problems as people and businesses flee to the suburbs and other states permanently in response to the virus, harsh shutdown laws, high taxes, and urban civil disorder.

For most local governments, however, tax revenues should stay quite strong, as during the last recession. If governments hold spending flat for a couple of years, they should be fine. News stories often call flat spending a “cut.” Let’s say a city passed a budget pre-virus proposing to increase spending 5 percent from $100 million to $105 million, but now with the recession the city prudently decides to withdraw the $5 million increase. That is not slashing or draconian, but it is often portrayed as such.

Anyway, many cities are making sensible and modest budget adjustments. The City of Boston had planned to increase its budget $154 million or 4.4 percent in 2021, but with the recession, it has trimmed $65 million from the increase by freezing hiring, cutting police overtime, and other adjustments. San Antonio’s budget will be roughly flat next year as it trims such items as street improvement projects and economic development incentives, while imposing a hiring freeze, employee furloughs, and cuts to executive pay.

State and local governments are not subdivisions of the federal government. They have the power to adjust their spending, taxes, and borrowing to handle the recession. They can also speed the return to economic growth by removing regulatory barriers to entrepreneurs who want to start businesses and create jobs. More businesses and jobs mean more revenue for governments.

The more aid that Congress provides, the less incentive for states and cities to improve operational efficiencies and to deregulate to spur broad-based economic growth.