Attorney General Jeff Sessions writes in Sunday’s Washington Post:

Drug trafficking is an inherently violent business. If you want to collect a drug debt, you can’t, and don’t, file a lawsuit in court. You collect it by the barrel of a gun.

Sessions correctly understands a major source of crime in the drug distribution business: people with a complaint can’t go to court. But he jumps to the conclusion that “Drug trafficking is an inherently violent business.” This is a classic non sequitur. It’s hard to imagine that he actually doesn’t understand the problem. He is, after all, a law school graduate. How can he not understand the connection between drugs and crime? Prohibitionists talk of “drug-related crime” and suggest that drugs cause people to lose control and commit violence. Sessions gets closer to the truth in the opening of his op-ed. He goes wrong with the word “inherently.” Selling marijuana, cocaine, and heroin is not “inherently” more violent than selling alcohol, tobacco, or potatoes.

Most “drug-related crime” is actually prohibition-related crime. The drug laws raise the price of drugs and cause addicts to have to commit crimes to pay for a habit that would be easily affordable if it were legal. And more dramatically, as Sessions notes, rival drug dealers murder each other–and innocent bystanders–in order to protect and expand their markets.

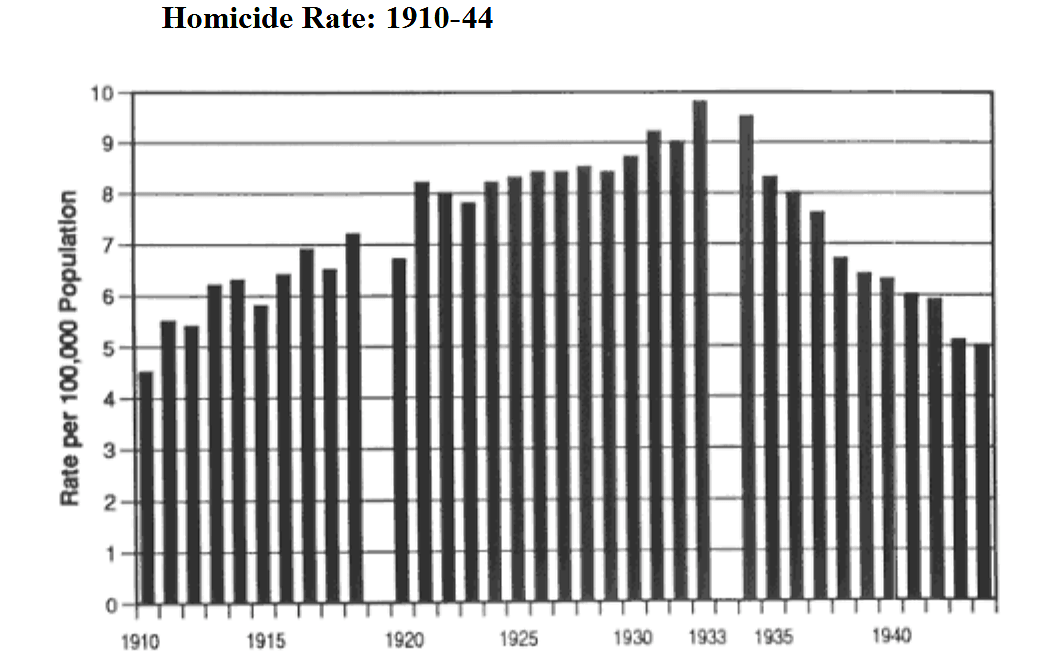

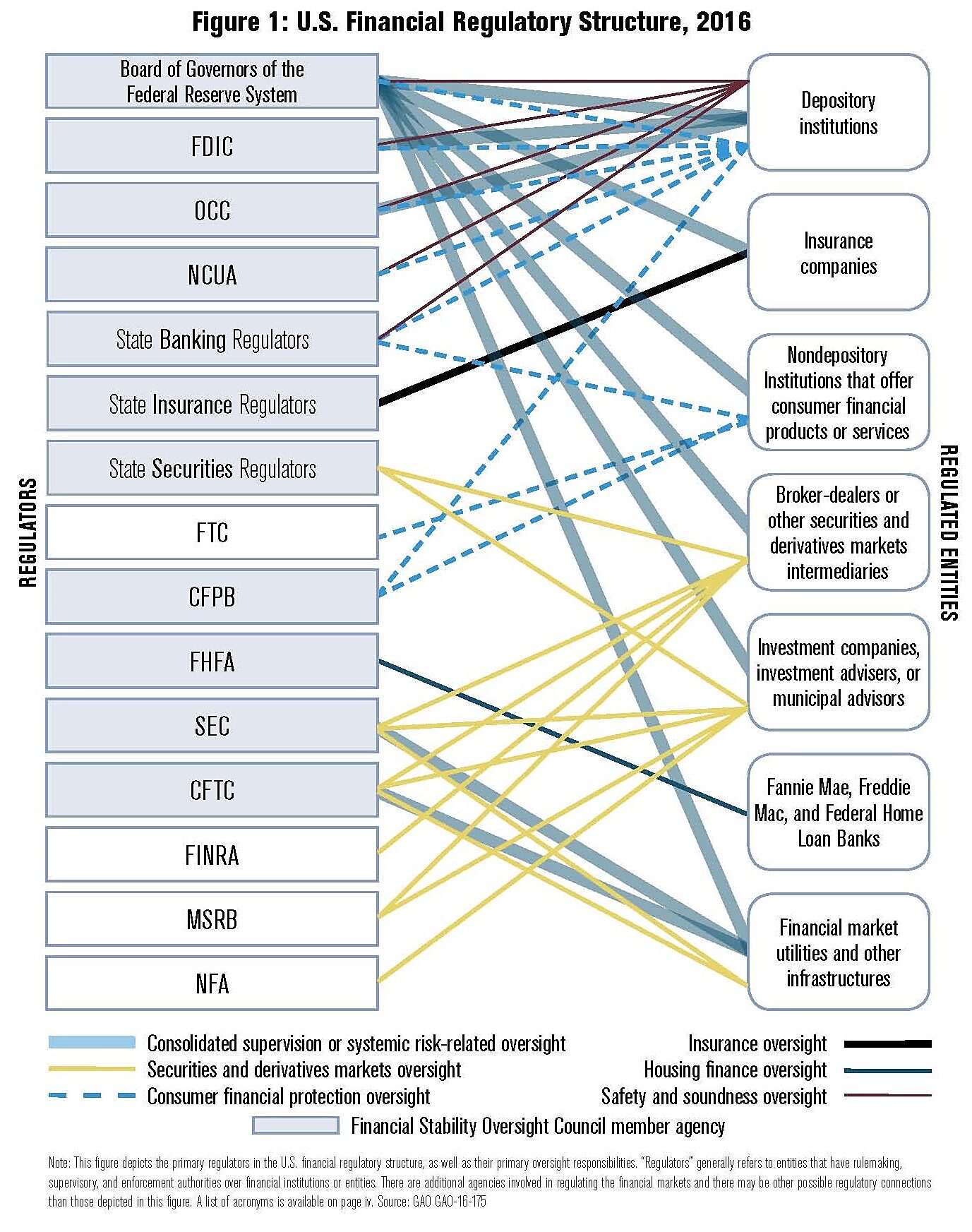

We saw the same phenomenon during the prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s. Alcohol trafficking is not an inherently violent business. But when you remove legal manufacturers, distributors, and bars from the picture, and people still want alcohol, then the business becomes criminal. As the figure at right (drawn from a Cato study of alcohol prohibition and based on U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 [Washington: Government Printing Office, 1975], part 1, p. 414) shows, homicide rates climbed during Prohibition, 1920–33, and fell every year after the repeal of prohibition.

Tobacco has not (yet) been prohibited in the United States. But as a Cato study of the New York cigarette market showed in 2003, high taxes can have similar effects:

Over the decades, a series of studies by federal, state, and city officials has found that high taxes have created a thriving illegal market for cigarettes in the city. That market has diverted billions of dollars from legitimate businesses and governments to criminals.

Perhaps worse than the diversion of money has been the crime associated with the city’s illegal cigarette market. Smalltime crooks and organized crime have engaged in murder, kidnapping, and armed robbery to earn and protect their illicit profits. Such crime has exposed average citizens, such as truck drivers and retail store clerks, to violence.

Again, to use Sessions’s language, cigarette trafficking is not an inherently violent business. But drive it underground, and you will get criminality and violence.

Sessions’s premise is wrong. Drug trafficking (meaning, in this case, the trafficking of certain drugs made illegal under our controlled substances laws) is not an inherently violent business. The distribution of illegal substances tends to produce violence. Because Sessions’s premise is wrong, his conclusion–a stepped-up drug war, with more arrests, longer sentences, and more people in jail–is wrong. A better course is outlined in the Cato Handbook for Policymakers.