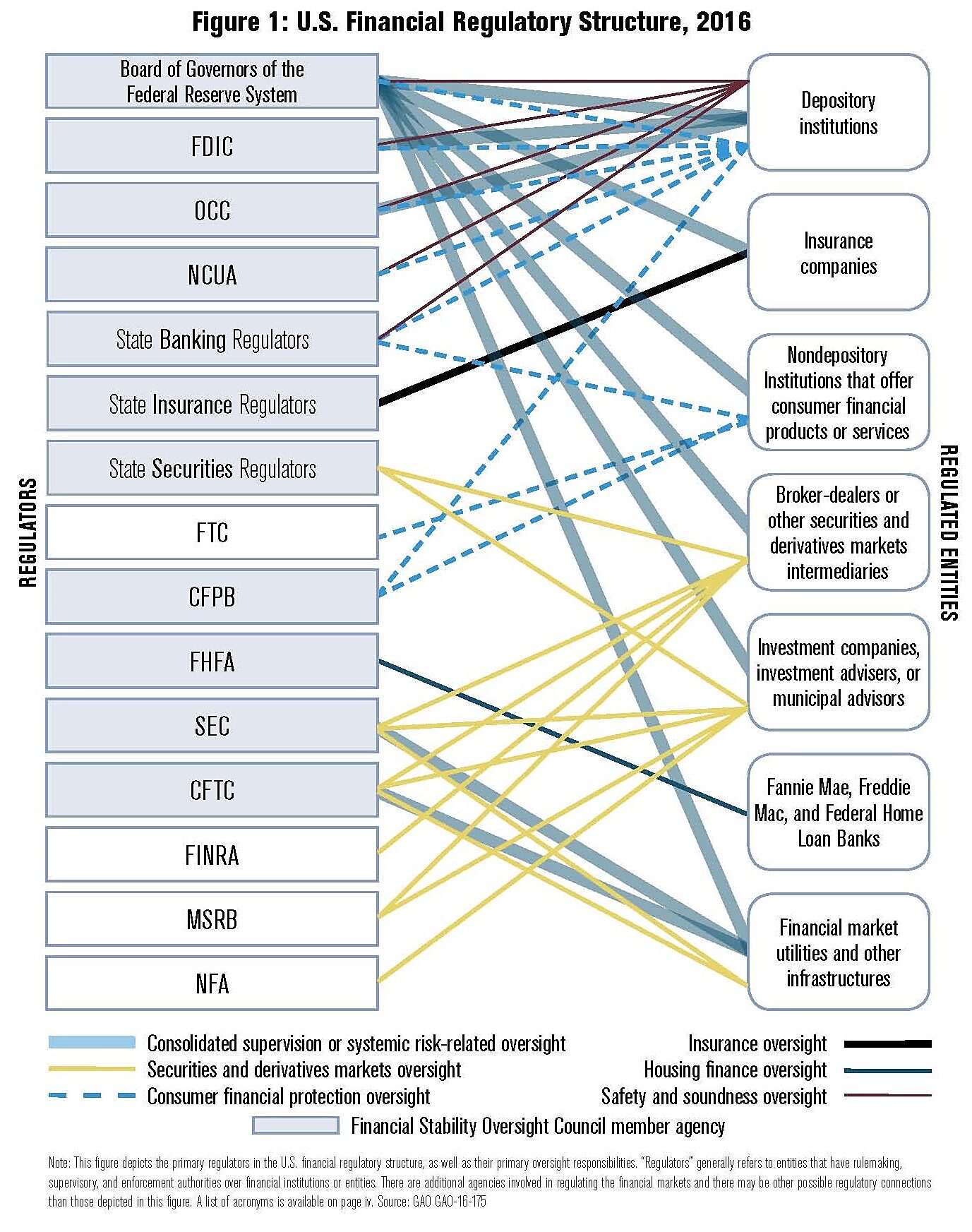

On Monday, the Treasury Department released the first of four planned reports on the U.S. financial system. While the 150-page report, focusing on banks and credit unions, includes a number of observations and recommendations worth discussing, there is one page I’d like to highlight here. It’s a single chart. And yet it speaks volumes about the current state of regulation in the financial sector. Here’s the chart:

Those in Washington often talk about the “alphabet soup” of federal agencies. We do love our acronyms here. But this chart shows that the financial sector has a complete soup all of its own. There are nine federal regulators who oversee the financial sector. Additionally, each state has its own regulators, typically one each for securities, insurance, and banking. Plus, there are the self-regulatory organizations—quasi-private bodies whose decisions can have the effect of law on the companies and individuals they oversee. A single organization can be subject to as many as six regulators. An organization that does business in multiple states can potentially be subject to regulation in each of them, in addition to regulation at the federal level.

There are two key problems with this kind of overlapping and duplicative regulation. First, there is the compliance burden. A broker-dealer in the securities markets, for example, must (with the help of expensive lawyers) thoroughly review and understand the regulations and rules issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board, the National Futures Association, and at least one state securities board. This requires not only understanding the rules of each regulator, but also how they intersect with one another. The broker-dealer must then (with the help of expensive lawyers) devise a series of compliance protocols to ensure that each of its employees, in each of their separate duties, acts within the confines of the regulations.

Second, such a high compliance cost creates barriers for new companies and new products. If a bank wants to try offering a new type of loan, it must ensure that the new product complies with all of the rules of every one of its regulators. Anyone with a bank account has probably noticed the massive changes new technology has brought to the financial sector. Being able to deposit a check using a smart phone is a great convenience. But before any bank rolled out that service, their lawyers had to ensure that the application’s features complied with all existing regulation. Furthermore, the bank had to consider whether any one of its regulators was likely to introduce new regulation that would affect the proposed service. There may be (and I would guess it is very likely there are) many products that consumers would like that banks are unwilling to offer because of the high cost of compliance and risk of getting that compliance wrong.

These barriers are even more challenging to new companies looking to enter the market. The technological changes that have made mobile banking possible have also opened the door to new ways of exchanging value outside of traditional banks. Anyone with a new idea will want to vet this idea with regulators before investing too much capital. And yet to conduct a vetting process, the entrepreneur will need to contact not one but often a half dozen regulators, each of whom might express a different view of the proposed product and a different set of concerns.

These regulatory schemes are no laboratories of democracy. This chart shows a stunning pile-up of regulators and regulations. It is one thing to talk about how regulation is stifling innovation and growth. It is another to see such a stark illustration of what this web actually looks like.