New data from the Congressional Budget Office show that federal tax revenues are soaring. Despite the Republican tax cuts of 2017 and the ongoing pandemic, taxes are pouring into the U.S. Treasury. If Congress restrains its spending appetite, this is good news as it will reduce the government’s dangerously high budget deficits.

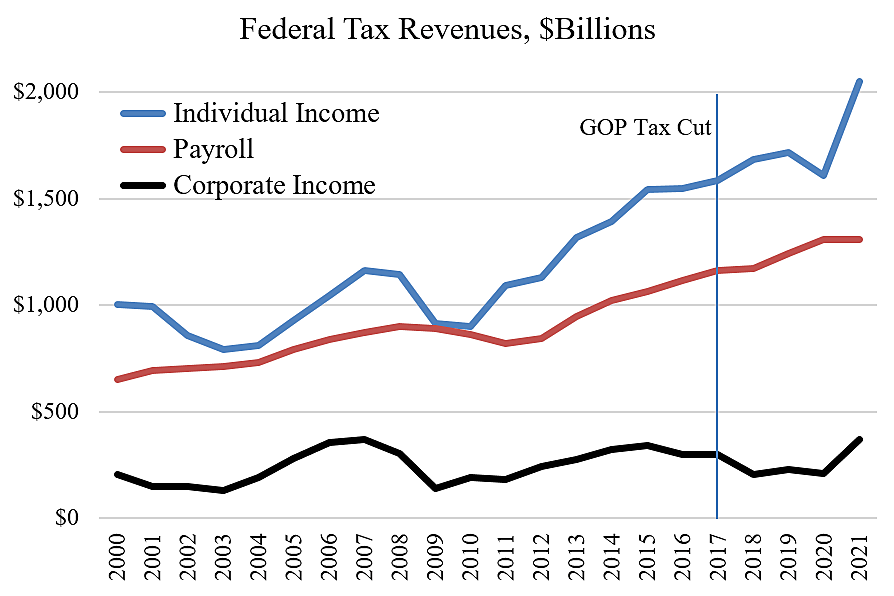

The chart below shows the major sources of federal revenues from fiscal 2000 to fiscal 2021, which ended September 30. The GOP tax cuts were effective January 2018, which was part way through fiscal 2018.

A few observations:

- Income tax revenues gyrate with economic cycles. Payroll tax revenues are more stable but stagnated after the recession a decade ago when employment was slow to recover.

- Individual income tax revenues rose in 2018 and 2019, fell in 2020 during the pandemic, then rose sharply in 2021.

- After the GOP tax bill passed, CBO projected that individual income tax revenues would rise to $1.900 trillion by 2021, but they came in 8 percent higher than projected at $2.052 trillion.

- Corporate tax revenues stagnated from 2018 to 2020 but then rose sharply in 2021.

- After the GOP tax bill passed, CBO projected that corporate tax revenues would rise to $327 billion by 2021, but they came in 13 percent higher than projected at $370 billion.

- Revenues in 2021 are higher than projected even though GDP for 2021 is down 2 percent from what CBO had projected after the tax bill passed.

Total federal tax revenues were $3.32 trillion in 2017, $3.33 trillion in 2018, $3.46 trillion in 2019, $3.42 trillion in 2020, and $4.05 trillion in 2021. Revenues in 2021 are 22 percent higher than prior to the tax cut in 2017.

Congress should use the current revenue gusher to reduce dangerously high deficits and debt. Government debt in the United States at 141 percent of gross domestic product is above the average of other high-income countries, and it is well into the danger zone above 100 percent of GDP where it appears to reduce economic growth.

The government is currently enjoying a revenue bounty, but Congress should not squander it on new spending. Instead, policymakers should encourage growth by reducing regulations, and they should use rising revenues to reduce perilously high deficits and debt.