Last week, The New York Times published an article subtitled, “In Desperately Poor Rwanda, Most Have Health Insurance.” The main theme was the contrast between Rwanda’s compulsory health insurance system and the as-yet-non-compulsory U.S. health insurance market:

Rwanda has had national health insurance for 11 years now; 92 percent of the nation is covered, and the premiums are $2 a year.

Sunny Ntayomba, an editorial writer for The New Times, a newspaper based in the capital, Kigali, is aware of the paradox: his nation, one of the world’s poorest, insures more of its citizens than the world’s richest does.

He met an American college student passing through last year, and found it “absurd, ridiculous, that I have health insurance and she didn’t,” he said, adding: “And if she got sick, her parents might go bankrupt. The saddest thing was the way she shrugged her shoulders and just hoped not to fall sick.”

I don’t see anything absurd here, but I do see something remarkable. Rwanda is so poor, its per capita income is about 1 percent that of the United States ($370 vs. $39,000). Its health care sector is an international charity case: “total health expenditures in Rwanda come to about $307 million a year, and about 53 percent of that comes from foreign donors, the

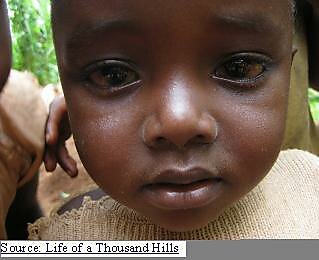

largest of which is the United States.” That’s roughly $32 per person per year, which doesn’t buy much. Dialysis is “generally unavailable.” As are many treatments for cancer, strokes, and heart attacks, making those ailments “death sentences” more often than in advanced nations. Life expectancy at birth is 58 years, compared to 78 years in the United States. Rwandan children are 15 times more likely to die before their first birthday (7 vs. 107 deaths per 1,000 live births) and 25 times more likely to die before turning five (8 vs. 196 deaths per 1,000 live births) than U.S.-born children. (If you want to meet some Rwandan kids struggling to make it to age 5, read my friend’s blog, Life of a Thousand Hills.) And yet, the saddest thing is a healthy-but-uninsured American college student.

What the Times sees as a paradox isn’t really a paradox. Yes, the poorer nation has a higher levels of health insurance coverage. But the wealthier nation does a better job of providing medical care to everyone, insured and uninsured alike. The Times reports that Rwanda’s national health insurance system isn’t fancy, “But it covers the basics,” including “the most common causes of death — diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, malnutrition, infected cuts.” Surely, the Times must know that anyone walking into any U.S. emergency room with any of those conditions would be treated, regardless of insurance status or ability to pay. The same is true of other acute conditions, like heart attacks and strokes, for which uninsured Americans receive better treatment than insured Rwandans. True, some uninsured Americans end up filing for bankruptcy, but let’s be clear: while bankruptcy is no day at the beach, suffering bankruptcy because you got the treatment is better than suffering death because you didn’t. (As for dialysis, the United States already has universal coverage for end-stage renal disease through the Medicare program.) The Healthcare Economist puts it this way: “Would you rather be sick in the United States without insurance or sick with insurance in Rwanda?” You get the point. If there’s a paradox here, it’s that insurance status does not necessarily correlate with access to medical care: uninsured people in the wealthy nation actually have better access to care than insured people in the poor nation.

An even bigger paradox, though, is Rwandan attitudes toward the United States. The United States generates many of the HIV treatments currently fighting Rwanda’s AIDS epidemic, as well as other medical innovations saving lives there and around the world. More than any other nation, we create the wealth that purchases those and other treatments for Rwandans and other impoverished peoples. The United States is probably closer to providing universal access to medical care for its citizens — and, indeed, the whole world — than Rwanda. Rwanda’s “universal” system leaves 8 percent of its population uninsured. Though official estimates put the U.S. uninsured rate at 15.4 percent, the actual percentage is lower; and again, uninsured Americans typically have better access to care than insured Rwandans. The real paradox is here that Rwandan elites think the United States is doing something wrong. Why?

Here’s one answer: Rwanda’s government explicitly guarantees health insurance to its citizens, and for some people that guarantee has value apart from any health improvements or financial security that may result. Dr. Agnes Binagwaho, “permanent secretary of Rwanda’s Ministry of Health,” illustrates:

Still, Dr. Binagwaho said, Rwanda can offer the United States one lesson about health insurance: “Solidarity — you cannot feel happy as a society if you don’t organize yourself so that people won’t die of poverty.”

Set aside that a (permanent) third-world bureaucrat is telling the United States how to keep people from dying of poverty. Binagwaho cannot feel happy without that government-issued guarantee.

How might such a guarantee increase happiness? It could make people happier by reassuring them that they themselves will be healthier and more financially secure (self-interest), or that others will be (altruism). Yet altruism and self-interest probably cannot explain the “happiness benefits” that people enjoy when governments guarantee health insurance. As I have argued elsewhere, the jury is out on whether broad health insurance expansions like ObamaCare result in better overall health; they may, but it is entirely possible that they would not. The jury is also out on whether ObamaCare will produce a net increase in financial security. It will subsidize millions of low-income Americans, but it will also saddle them with high implicit taxes that could trap millions of them in poverty. Meanwhile, ObamaCare’s new taxes will reduce economic growth and destroy jobs. If such a guarantee doesn’t improve health or financial security, it’s not worth much in terms of altruism or self-interest.

But there’s another potential “happiness benefit” that might accrue to supporters of a government guarantee of health insurance: it could make them happier by allowing them to signal something about themselves — e.g., that they are compassionate. If people use a government guarantee of health insurance in this way, that could explain why Rwandan elites feel bad for uninsured Americans. They may feel empathy for uninsured Americans because they perceive the American electorate has not sent uninsured Americans a valuable signal (“We care about you!”). Meanwhile, the act of expressing pity for uninsured Americans allows Rwandan elites to signal something about themselves (“We are compassionate!”). Robin Hanson has a lot to say about why people might use health insurance and medical care to signal loyalty and compassion.

My hunch is that this is an under-appreciated reason why some people support universal coverage: a government guarantee of health insurance coverage provides its supporters psychic benefits — even if it does not improve health or financial security, and maybe even if both health and financial security suffer.

If that’s the case, then we’re facing the same problem that Charles Murray identified in Losing Ground, his seminal work on poverty:

Most of us want to help. It makes us feel bad to think of neglected children and rat-infested slums…The tax checks we write buy us, for relatively little money and no effort at all, a quieted conscience. The more we pay, the more certain we can be that we have done our part, and it is essential that we feel that way regardless of what we accomplish…

To this extent, the barrier to radical reform of social policy is not the pain it would cause the intended beneficiaries of the present system, but the pain it would cause the donors. The real contest about the direction of social policy is not between people who want to cut budgets and people who want to help. When reforms finally do occur, they will happen not because stingy people have won, but because generous people have stopped kidding themselves.

One thing is for certain. When Rwandan elites pity uninsured Americans, there is something very interesting going on.

While I’m at it, the health-policy advice I offered to China and India also applies to Rwanda:

Does not the fact that “these countries lack the fiscal resources required for universal coverage because of their…low average wages” suggest that many residents have more pressing needs than health insurance? For things that might just deliver greater health improvements? In a profession where universal coverage is a religion, such questions are heresy, I know.

China and India are in the process of a slow climb out of poverty. It is entirely possible that the best thing those governments could do to improve [health care] markets and population health would be to enforce contracts, punish torts, contain contagion, and nothing else.

Of course, if Rwandan elites support universal coverage largely because they want to signal something about themselves, this advice may fall on deaf ears.