Over the last few days the Wall Street Journal has run two articles suggesting that the No Child Left Behind Act has been somewhat successful. But that’s not supported by the federal government’s own measure, the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

The WSJ’s first article appeared on Saturday, and while focusing on the stagnation of high-achieving students, it asserts that NAEP exams show “dramatic progress—sometimes double-digit increases—for the lowest achievers over the last two decades, especially after No Child Left Behind.”

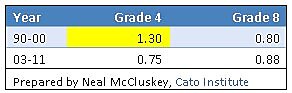

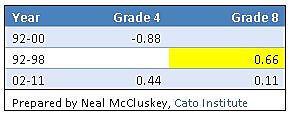

Last month I debunked the idea that historically struggling groups have seen dramatic improvements under NCLB, laying out the data from numerous NAEP tests. Quite simply, looking at score gains per year, there were many periods before NCLB that saw faster improvements. Below are two more tables from the latest NAEP scores, released a couple of weeks ago. These are for the so-called “main” NAEP, which is not nearly as valuable as the long-term trends exam for seeing historical patterns, but the WSJ cites it and it does contain new information. The results are for the bottom 10 percent of performers.

As always, at what year one could start crediting results to NCLB is debatable. (Actually, you can never simply look at NAEP scores and attribute them to one factor because so many variables influence outcomes.) That date cannot be earlier than 2002, the year the law was enacted, and probably should be 2003, by which time most of the regulations were written and the law began to take real effect. To deal with this problem, the tables include only years that fully include NCLB or do not include it at all. Also note that there are two pre-NCLB time bands for reading because there are no 2000 8th grade reading scores.

Mathematics, 10th Percentile

Reading, 10th Percentile

Once again, there is is no pattern of faster improvement under NCLB than before it. Highlighting periods with greater growth than under NCLB, you can see that in 4th grade math improvements were faster before NCLB than after. In 8th grade math, it’s essentially a dead heat. In 4th grade reading, there’s sizable improvement under NCLB, and in 8th grade reading there’s an appreciable advantage before NCLB.

The second WSJ piece that gives NCLB undue credit is an op-ed from Kevin Chavous. Chavous, a tremendous advocate for school choice, implies that NCLB supplies “accountability” needed to make American kids competitive with their international peers. But as we’ve seen, there’s precious little evidence that NCLB has done anything to improve educational outcomes. Meanwhile, it has cost us a mint, with Department of Education k‑12 spending rising from $27.3 billion in 2001 to $37.9 billion in 2011.

Unfortunately, Chavous’s piece seems more aspirational than reality-based, as is often the case in education policy. “We must try to make schools and teachers accountable,” he seems to be saying. “Heaven knows the states won’t do it!”

The need to deal in reality is why Mr. Chavous’ main concern—getting school choice—is so crucial. Government schooling will never be fundamentally changed because those who would be held accountable—teachers, administrators, bureaucrats—have by far the most motivation to be involved in education politics, the greatest ability to organize, and hence the biggest store of political power. Their livelihoods, after all, are at stake. And what do they want? What we’d all probably like: as much pay as possible with as little accountability.

The only way to end employee domination of education is to fundamentally change the system: instead of having politics control schooling, let parents control education money so they can take their children out of schools they don’t like and put them into those they do. Don’t force them to undertake the endless, hopeless warfare of having to form coalitions, try to get politicians’ ears, spur politicians to move and, if they can ever get decent changes, then force them to constantly fight to keep the reforms against opponents with full-time lobbyists and political machines. No, let them vote with their feet, right away, and get their children the education they need.

NCLB is, by most indications, an abject failure, and the very nature of government schooling doomed it to be so.