Over at The Incidental Economist, Austin Frakt challenges a couple of claims I made on NPR about Medicare reform. (Here’s how NPR reported my comments in print.)

My claims are pretty simple.

- If Medicare subsidizes enrollees by giving them a fixed amount of money, much like Social Security does, they would be more cost-conscious than they are under the current open-ended subsidy, because enrollees who avoid wasteful spending would themselves get to keep the savings. Put more plainly, people spend their own money more carefully than they spend other people’s money.

- Health insurers and health care providers would compete to serve these cost-conscious Medicare enrollees on the basis of both cost and quality. Prices would fall while quality improves.

I’m not really sure to what extent all this would occur under the Medicare reforms the House passed a couple of weeks ago, because we don’t yet know to what extent each enrollee’s subsidy would resemble a fixed amount of money.

Here’s what Frakt does with my claims:

[A]s I heard these words I wondered if we had any evidence on hand about the relationship between lower premium subsidies and health care cost inflation. Indeed we do! Premiums in the commercial market are subsidized by the government at a lower rate than those in Medicare. [Emphasis added.]

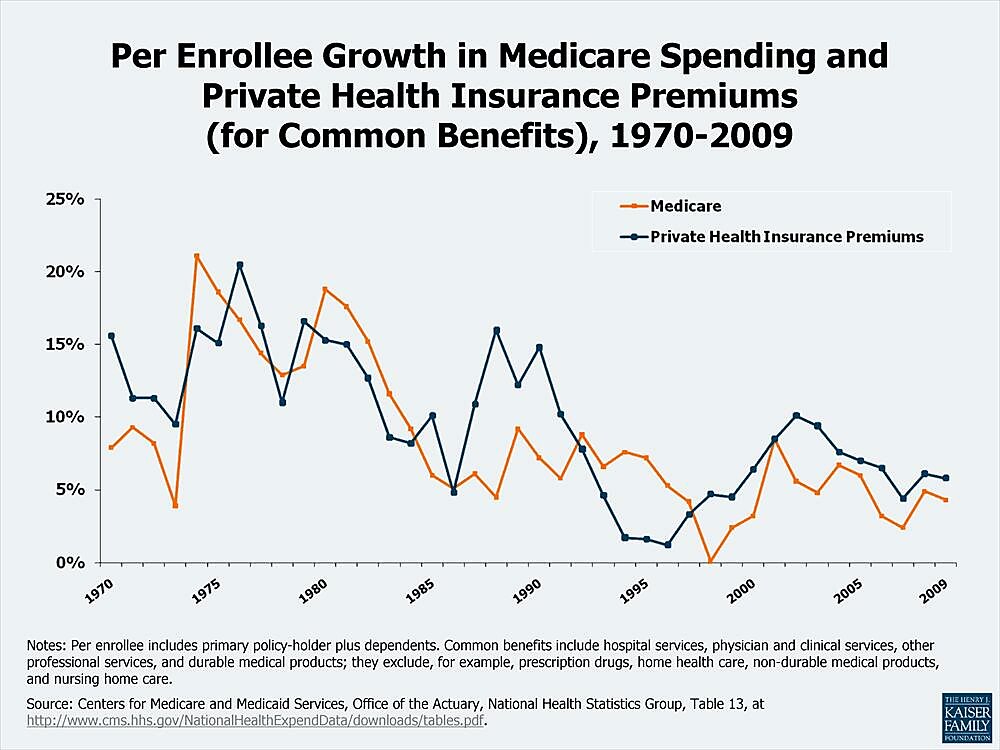

He then throws up the chart, shown below the jump, showing that for common benefits, the rate of growth in per-enrollee spending is “pretty similar” in Medicare and private insurance. He concludes: “With data like this, I think we need to reexamine some of our theories about what lower premium subsidies can do.”

Oy, where to begin?

First, Frakt does not actually challenge my claim. My claim is that voucher-like Medicare reforms will lead to reductions in the per-unit cost of producing certain goods and services, and therefore to lower prices. Frakt responds with data on health care spending. When someone predicts that P will fall, introducing into evidence what has historically happened to P x Q is no kind of rebuttal. The confusion Frakt sows is rooted in the fact that both prices and spending can be accurately described as costs. Such confusion could be avoided were everyone to honor Cannon’s First Rule of Economic Literacy: Never say costs when you mean spending.

Second, though the tax preference for employer-sponsored health insurance distorts relative prices the same way an open-ended subsidy does, it is not a subsidy. This isn’t really relevant to the matter at hand, but it’s worth emphasizing to avoid such silliness as this.

Third, it would be great if there existed one chart that would settle once and for all whether Medicare or a free market does a better job of containing costs. Alas, this is not that chart. Frakt uses it to make a less-ambitious point about the effects of larger versus smaller policy-induced price distortions, but its shortcomings nevertheless confound that comparison, too. In addition to measuring increases in spending (whose effect on social welfare is ambiguous) rather than increases in cost (which are always bad), this chart handicaps private insurance by leaving off three or four years of explosive growth in per-enrollee Medicare spending (1966–1969). Worse, it reeks of endogeneity problems. Amy Finkelstein finds evidence that Medicare itself increases spending among those with private insurance (mostly by increasing hospital capacity), and that this effect has grown over time. Moreover, as Medicare spending rises, so do average marginal tax rates, which increases the price distortion created by the tax exclusion, which increases spending on private insurance. For all the play it gets on the Left, this chart serves no useful purpose that I can discern. Economists should be embarrassed to use it. If it were a farm animal, and social scientists farmers, they would have to take it behind the barn and put a bullet in its head.

Fourth, we are not yet at the point where we need to reexamine the theory that demand curves slope downward. There is ample evidence to show that Medicare enrollees will respond to voucher-like reforms by choosing more economical health plans, and that health plans and providers will respond with greater efficiency. Thomas Buchmueller reports:

Two notable experiments…took place in the mid-1990s: the University of California (UC) and Harvard University both offered a menu of plans that varied in generosity, but adopted a “fixed dollar contribution” policy. The plans also varied significantly in cost, so employees had a greater incentive to consider price when selecting a health plan…

In both cases, employees were quite sensitive to price, and were willing to switch plans to save as little as $5 per month in out-of-pocket premiums…In addition to this demand response, participating insurers lowered their premiums in order to compete for enrollment.

Fifth, there is plenty of evidence that prices can and do fall in health care — from research on the markets for laser-eye and cosmetic surgery, to the work of Clay Christensen and his colleagues, to the research of David Cutler and Mark McClellan. (If spending increases while prices are falling, it is because changes in Q dominate changes in P — which could be due to all these open-ended government subsidies and other price distortions.)

Finally, as a response to the general theme of that NPR story: we’re a long, long way from the point where we have to worry that reductions in the growth of Medicare spending are going harm enrollees’ health. Relying on data from the Dartmouth Atlas, President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers reminds us that “nearly 30 percent of Medicare’s costs [spending!] could be saved without adverse health consequences.” And there is plenty of evidence, from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment and elsewhere, that plans with greater cost-sharing or care management reduce utilization without harming patients’ health.

I cannot fathom what has opponents of Medicare vouchers so spooked. It cannot be the effects that vouchers would have on Medicare enrollees and taxpayers.