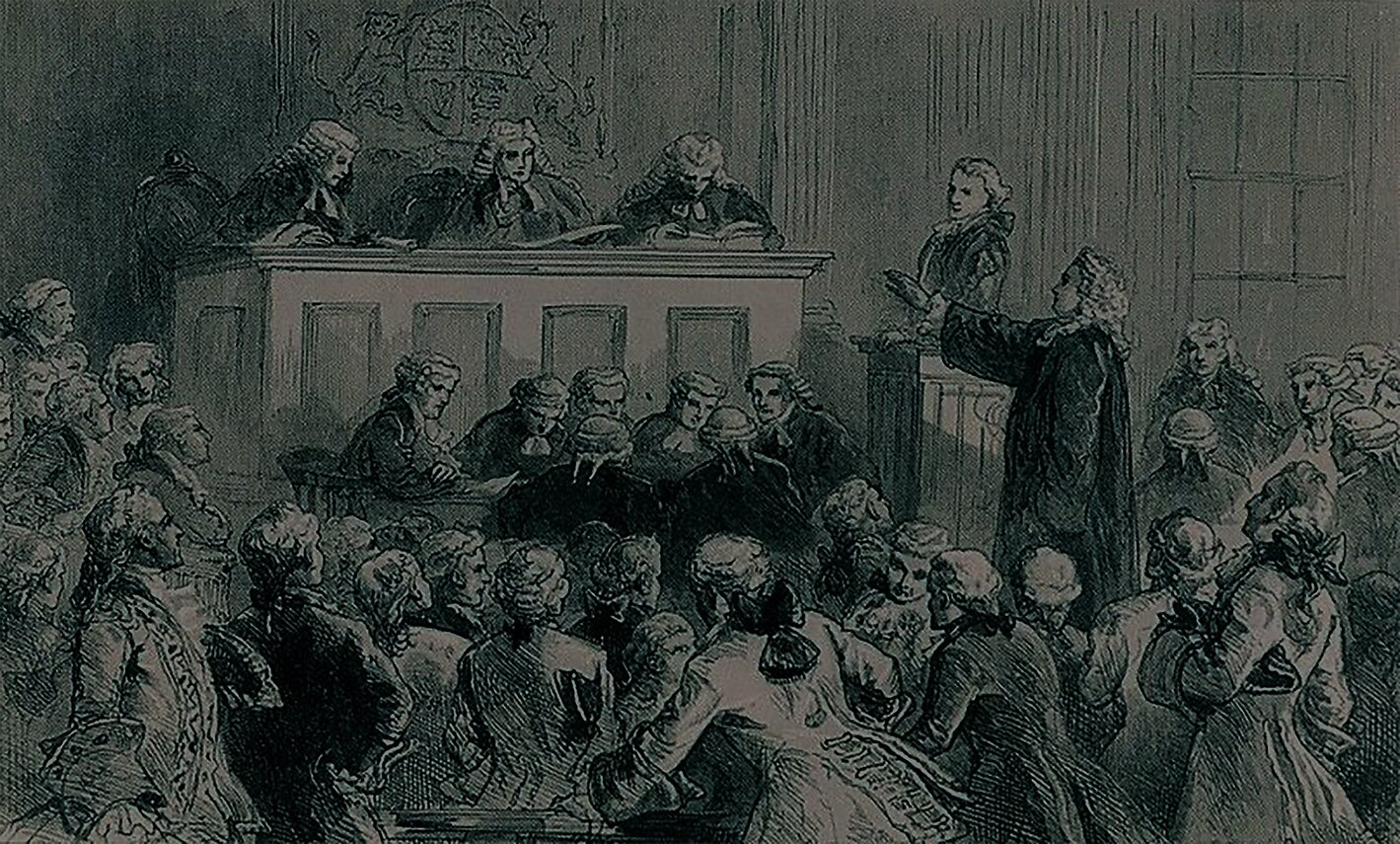

The judgments of English courts were as much the law of the land as royal edicts or acts of Parliament.

This law, known as the common law, was the body of law that the Founders studied, shaped, and responded to in the years before they created the U.S. Constitution.

Two famous cases were foundational in their understanding of how the criminal justice system should function.