One of the few hopeful, “glass-half-full” thoughts I had after Donald Trump won the election in 2016 was that the new president would prove to be the best salesman of free trade since Adam Smith. No, I wasn’t so deluded to think he’d articulate the case for free trade and commit himself to removing all protectionist barriers. On the contrary, I assumed Trump’s reckless deployment of tariffs and other trade restrictions would backfire so spectacularly and expose the folly of protectionism so convincingly that the economically discredited philosophy would become politically radioactive, once and for all.

Well, the absence of any coherent, fresh ideas from the Democratic presidential aspirants that would differentiate their trade policies from President Trump’s suggests that maybe things haven’t played out as I had expected they would. Not yet, anyway.

The cost of Trump’s trade wars (the effects of tariffs on nearly $300 billion of imports and retaliation against nearly $200 billion of exports) has started to register on the Geiger counter, but we’re nowhere near Chernobyl levels yet. The economic pain has been concentrated in a few sectors and regions, and dulled by subsidies, fiscal stimulus, and (as of tomorrow, presumably) monetary stimulus. Of course, as this sugar high wears off and the economy slows, conditions are likely to worsen.

Will the Democrats be prepared to capitalize when this happens? Will any of the party’s presidential aspirants call out Trump’s tariffs? Will any repudiate protectionism? Can any lead the party back to the center on trade? According to all of the major polls, that’s exactly where most Democratic voters reside. It’s where most Republican voters reside, too.

The problem for Democrats is that distancing themselves from Trump’s protectionism means distancing themselves from the prevailing Democratic Party orthodoxy. For the past quarter century, Democrats have been skeptical of—when not outright hostile to—trade and globalization.

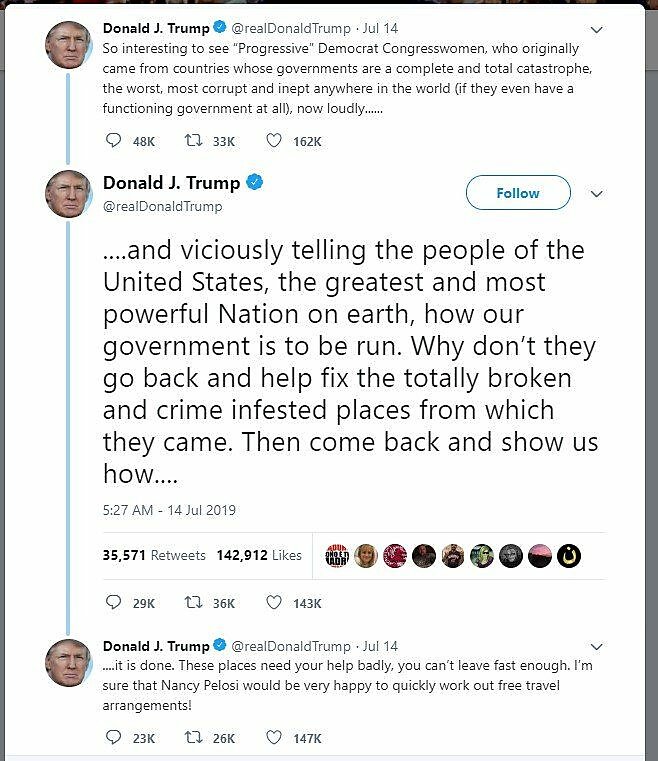

In many regards, Trump’s right-wing, protectionist, nationalist trade policies are barely distinguishable from the ideas espoused by the Democratic Party’s anticorporate, protectionist left-wing, who still hold sway over trade policy. Both favor interventions to achieve particular (often identical) outcomes, such as compelling Americans to “Buy American,” limiting imports, penalizing developing countries that don’t adopt rich country labor and environmental standards, taxing outsourcing, impeding labor market adjustment, and halting the alleged encroachment of the dark forces of globalization. To the right, those dark forces are the faceless foreign bureaucrats committed to usurping U.S. sovereignty. The left’s bugaboo are the multinational corporations, hellbent on weakening the rule of law and undermining democracy.

To those seeking the Democratic nomination for president, challenging the party’s protectionist plank may sound risky. After all, the party’s trade policy positions long have been bankrolled by organized labor, which—despite its absurd claims to the contrary—opposes trade liberalization, full stop, regardless of the fact that protectionism hurts U.S. workers (placing my bet here that the AFL-CIO does not endorse the USMCA, even after all of its conditions are met).

Voters on the far left, who will play an outsized role in selecting the nominee, tend to support the party’s protectionist platform because they’ve been misled to believe that trade only benefits big corporations and the rich. Senators Warren and Sanders have been instrumental in perpetuating that divisive fallacy. The facts are that the costs from the diminution of trade opportunities are borne primarily by smaller companies and households with lower incomes.

Protectionism is regressive. Free trade is progressive.

Although the subject was barely broached in the first two Democratic debates, the party’s positions on trade are going to matter in the 2020 election. Those positions will be shaped by debate among the candidates, the direction of the economy, and commentary in the media and on social media from now until the convention next summer. But Democrats should realize that voters from the center-left to the center-right want an alternative to Trump’s trade policies. They want to see the damage repaired.

Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership—which lives on as the Comprehensive Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership for the benefit of producers and consumers in 11 countries not called the United States—will make it that much more difficult to reverse the damage and rebuild commercial relationships when enlightened U.S. leadership recommits to that course. What they will find is that while the Trump administration (and, it now seems reasonable to conclude, the Republican Party more broadly) was indulging its protectionist nationalist grievances and playing hard to get (something Elizabeth Warren’s trade plan would double-down on by making prospective partners jump through all sorts of hoops), the EU, Canada, Mexico, China, Japan, Korea, and many countries in Latin America and Africa were pursuing and completing trade agreements, which have put and will continue to keep U.S. exporters at a huge disadvantage in many important markets across the globe.

Moreover, the World Trade Organization, which—along with its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade—has provided some semblance of institutional continuity and the rule of law in international trade for over 70 years, is under severe duress and could collapse, in large measure because of U.S. actions and inactions. The Trump administration’s defiance of the trade rules and preference for vigilantism is pushing the global economy toward breaking up into competing spheres of influence. That outcome would reduce the scope for economies of scale, impede the process of specialization, and tempt more and more governments into imposing discriminatory tariffs on products from countries in the “other” sphere or spheres.

The administration’s aggressive and unpredictable behavior has worked to undermine U.S. credibility abroad, which means not only that American commercial interests will suffer, but that U.S. geopolitical objectives going forward will become more difficult and more expensive to achieve. Team Trump has created some real problems that the next administration must fix. What solutions do the Democratic candidates offer?

The Republican Party and its congressional leadership have fallen in line behind Trump’s America-First protectionist nationalism, abandoning the center and center right, leaving the business community, moderate Republicans, and “Never Trumpers” desperate for alternatives. These developments gives Democrats an opening to distance themselves from protectionism and set their sights on reclaiming the vast middle ground on trade—from the center-left to the center right—that it ceded to the GOP in the mid-1990s. It can do that by offering a pro-trade alternative that voters see as reasonable and realistic, and focuses on repairing bilateral relationships, securing agreements that put U.S. entities back on equal footing, contributing constructively to repairing the WTO, and insisting on enforcement through the rules-based system of trade.

If any candidate is looking to history for inspiration, it was in 1934 that a Democratic Congress and a Democratic president rescued the ship of U.S. trade policy, after it had been stranded on rocky shores by Republican tariffs, by passing the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act.

The RTAA offered a way to begin digging the country (and the world) out of the protectionist hole that was dug by the Tariff Act of 1930 (aka, Smoot-Hawley) and its repercussions. The RTAA made it easier to negotiate, conclude, and enact bilateral trade agreements. The successes set the table for 23 countries to sign the original GATT in 1947, which was broadened and deepened incrementally over eight rounds of multilateral negotiations, culminating in the establishment of the WTO in 1995. This was the work of a bipartisan consensus in Washington that was initiated and nourished by Democrats, who understood the value of trade to economic growth and its centrality to fostering good relations among nations. Renewing that commitment in 2019 would be good for the party, the country, and the world.

Democrats—especially Sens. Warren and Sanders and others who call themselves “progressive”—should know that in the very same breath that they express opposition to trade agreements and preferences for tariffs, they endorse regressive taxation of life’s basic necessities: food, clothing, and shelter. Tariffs are not only taxes, but regressive taxes. There is an inverse relationship between income and percentage of income spent on goods. People with lower incomes spend higher percentages of their incomes on goods and lower percentages on services than do people with higher incomes. Imports account for the majority of the goods Americans consume. Furthermore, relatively high U.S. tariffs on products like clothing and footwear punish producers in poor countries disproportionately.

Maybe some sensible ideas will come to the fore during the debates over the next two nights, but as of now it seems that the Democratic candidates will remain hopelessly beholden to organized labor, environmental extremists, and anti-business, anti-capitalism, anti-globalization groups—even though the preponderance of Democratic voters favor trade, trade agreements, globalization, and U.S. global economic leadership. Likewise, there are millions of “Never Trumpers,” and centrist Republicans who became politically homeless when Trump commandeered the GOP and drove it to the nationalist, protectionist right.

The Democratic Party is long overdue for a serious, substantive debate over the objectives and tools of trade policy. Making a play for the center on trade would be the outcome that best serves the party and the country. Perhaps we’ll see evidence that debate has begun tonight.