The American Legislative Exchange Council has just released its latest Report Card on American Education, and will be hosting an event to launch it in Washington, DC, tomorrow, at the Heritage Foundation. I haven’t had a chance to get very far into it yet, but it was established on Monday of this week that ALEC can predict the future, so it’s certainly worth a look.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Sunlight Before Signing, Year Three

In last night’s State of the Union speech, President Obama called for tax law reforms he says we need. Cato scholars have their doubts about much of what was in the speech, but my interest was piqued by the fact that he said, “Send me these tax reforms, and I will sign them right away.”

You see signing them “right away” would again violate his 2008 campaign promise to post the bills sent him by Congress online for five days before signing them.

That’s a cheeky point, but it is time to focus on campaign promises and their honesty. The beginning of President Obama’s fourth year in office is roughly the beginning of his campaign for another term.

When I first began tracking President Obama’s Sunlight Before Signing promise, I joked with friends that it was career gold because I could write hundreds of blog posts for the next four years without thinking a new thought. Well, it’s not quite that good. This is post thirty-six in the SBS series.

(Each character in that last sentence was a link to a previous post. You can spend a whole day reviewing them!)

Last Thursday, January 19th, was the end of President Obama’s third year, so it’s time to review how he’s been doing with Sunlight Before Signing. It was the president’s first broken promise, and at the mid-point of the term he had popped just above 50% in his compliance.

How has he done in the ensuing year?

Well … meh.

Of the 90 bills that became law in the last year, 55 got the Sunlight Before Signing treatment. That’s a 61.1% average, good enough to earn a middle-school student a D.

| Number of Bills | Emergency Bills | Bills Posted Five Days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 124 | 0 | 6 |

| 2010 | 258 | 1 | 186 |

| 2011 | 90 | 0 | 55 |

| Overall | 472 | 1 | 247 |

Year three was stronger than the previous two, so President Obama’s overall Sunlight Before Signing record moves to 52.4%. That’s poor execution on a transparency promise that energized audiences on the 2008 campaign trail. But let’s dig a little deeper.

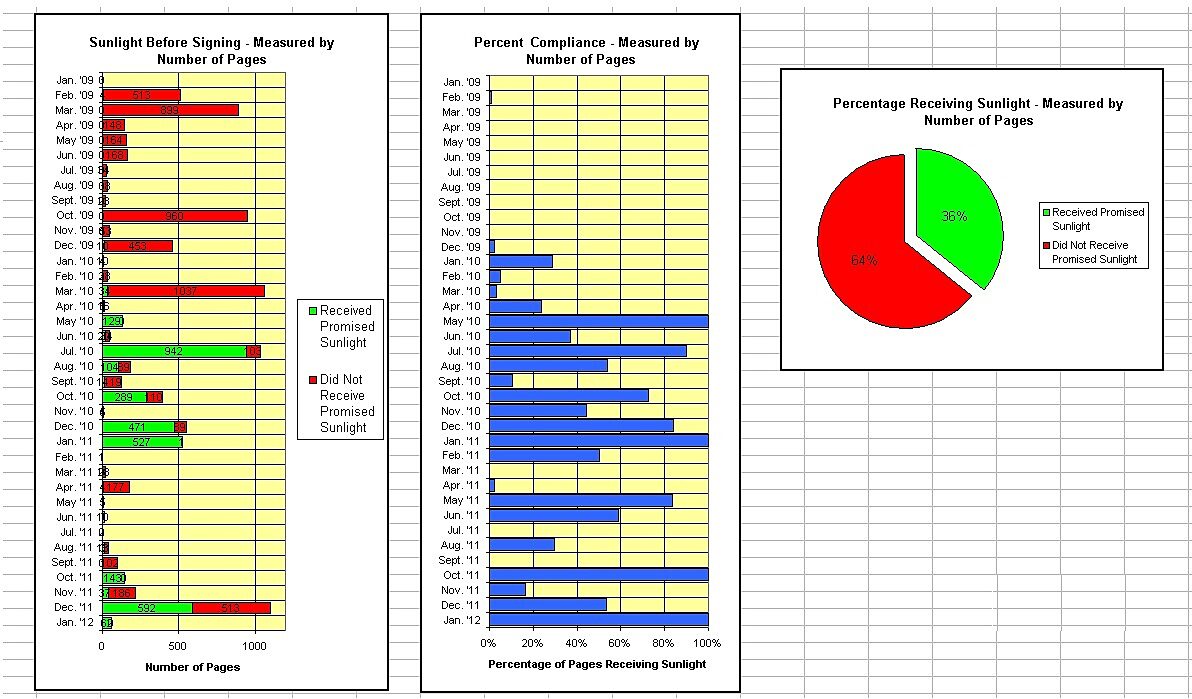

At the end of the second year, we did some analysis and graphing to explore the hunch that inconsequential bills get plenty of sunlight and the more important ones do not. We return to that analysis.

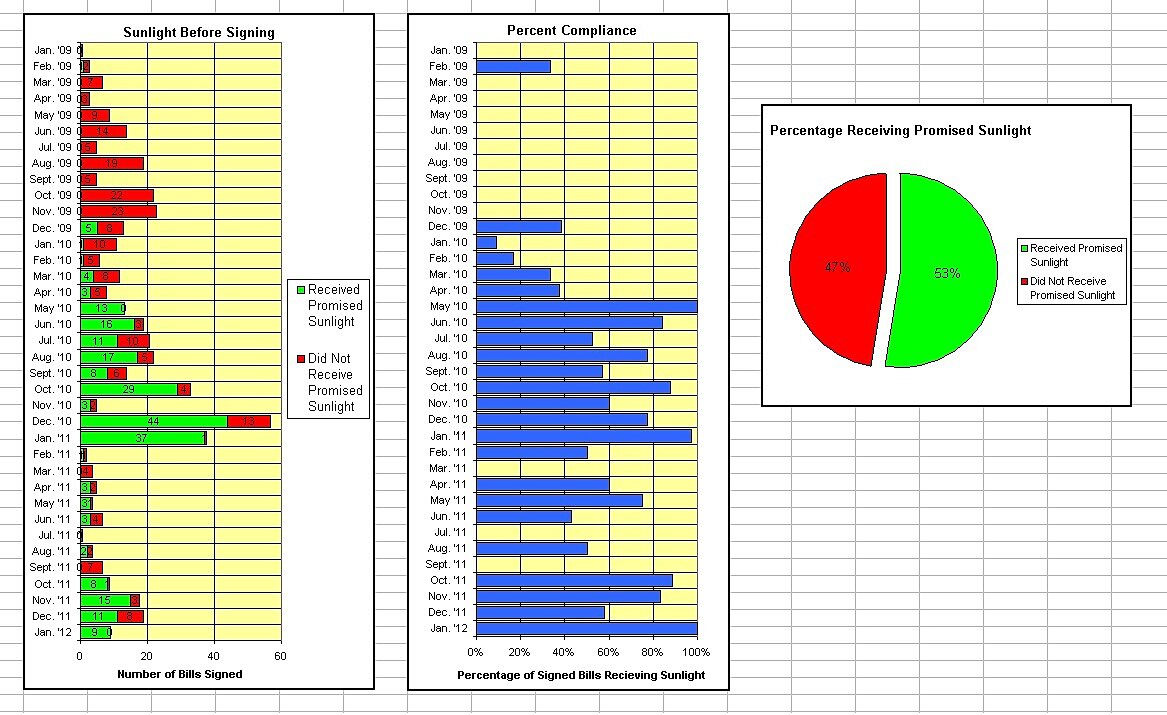

Our first look is at compliance with Sunlight Before Signing over time. The updated numbers show essentially the same as they did before. After a first year of outright failure, there has been improvement—nowhere near perfection, just improvement.

(You can also see that Congress’ output dropped dramatically in 2011. That’s a matter of indifference in terms of Sunlight Before Signing—and a good thing if you like limited government.)

Click on the image at right to see a chart of compliance and non-compliance by number of bills over time, then compliance as a percentage of bills over time, and, in the pie chart, that overall compliance figure.

We also investigated previously the hunch that important bills get less sunlight, while unimportant bills get more. Our first proxy for importance—a rough one—was the number of pages in the bills coming to the president. Generally speaking, longer bills are more important than shorter ones. The second set of charts (click on the left) show Sunlight Before Signing compliance and non-compliance over time by number of pages, compliance by percentage of pages, and overall compliance by number of pages. You can see that overall compliance drops well below 50% to about 36%.

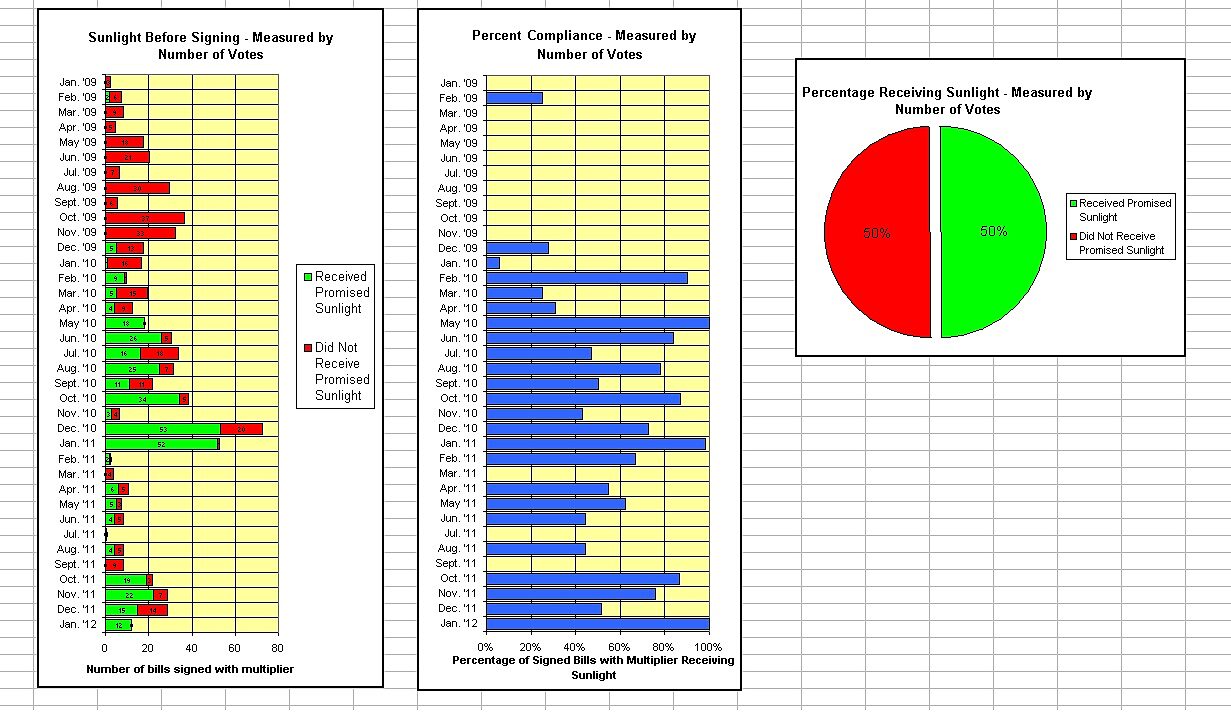

Another proxy for importance is the number of final passage votes a bill got in the House and Senate. Generally speaking—and it’s definitely not always true—more important bills are voted on in the House, the Senate, or both. Less important bills go through on voice vote, unanimous consent, and so on. (Sometimes important bills go through without votes because the political balances are so carefully struck. That’s good for Congress “getting things done,” but not good for transparency or your ability to oversee the government.)

Go ahead and click on the image to the right and you can see the charts reflecting Sunlight Before Signing compliance and non-compliance over time with multipliers given to bills getting one or two final votes. That result is not so decisive: compliance drops by a small amount to about 50%.

There’s still time for President Obama to execute on Sunlight Before Signing. He could make a real run at transparency by signalling right now—today—that all bills will get five-days online before he signs them. If Congress wants to finish appropriations this year at the last minute. They had better do that at the last minute plus five days or else the government will shut down.

Maybe that’s a silly idea. Maybe no president in his right mind would do something like that. If so, consider that President Obama promised to do exactly that when he campaigned for the presidency. If he was being fanciful during his last campaign, voters might consider that during his next campaign, just as they consider the credibility of all candidates. President Obama’s transparency promises have been unparalleled. His results … quite paralleled.

Perhaps President Obama is going to limp to the next election without fulfilling Sunlight Before Signing. The president could still score some real transparency points by publishing a machine-readable organization chart for the executive branch, with agencies, bureaus, programs, and projects all uniquely identified for computer processing. That would be big, and it would not be that hard.

In the meantime, here are the Sunlight Before Signing results for all the bills signed into law during President Obama’s third year.

[Brackets indicate a link from Whitehouse.gov to Thomas legislative database]

Related Tags

No Common Schools, No Peace?

Today is the mid-point of National School Choice Week, and we’re once again rockin’ to the oldies of prognostication. This time we’re going all the way back to the Mann. That’s Horace Mann, the “Father of the Common School” himself.

It is Mann who, among many things, is probably most responsible for introducing one of the deepest underlying sentiments supporting government schooling: that public schools will unify us and give us peace. As he waxed eloquent in his first annual report as Secretary of the newly-constituted Massachusetts State Board of Education:

Amongst any people, sufficiently advanced in intelligence, to perceive, that hereditary opinions on religious subjects are not always coincident with truth, it cannot be overlooked, that the tendency of the private school system is to assimilate our modes of education to those of England, where churchmen and dissenters, —each sect according to its own creed,—maintain separate schools, in which children are taught, from their tenderest years to wield the sword of polemics with fatal dexterity; and where the gospel, instead of being a temple of peace, is converted into an armory of deadly weapons, for social, interminable warfare. Of such disastrous consequences, there is but one remedy and one preventive. It is the elevation of the common schools.

How wrong Mann was.

Keep in mind that as of 1837, the year Mann gave his first address, some pretty impressive unifying things had happened in America despite education being grounded in families, private schools, and yes, churches. We’d established unified colonies; penned and ratified a Declaration of Independence that enunciated foundational American values; fought and won a war against the greatest military power on Earth; established a new nation; and created a national government based on a Constitution that — though it’s legs are under constant assault — still stands.

But let’s get to Mann’s prediction: Did “elevation of the common schools” end “social, interminable warfare”?

Not on your life. Indeed, by attempting to force diverse people into a monolithic system of government schools, it most likely exacerbated social tensions and sparked otherwise avoidable wars. To name just a few school-stoked conflagrations (both real and rhetorical):

- The Philadelphia Bible Riots of 1844, sparked by a dispute over whose version of the Bible — Roman Catholic, Protestant, or neither — would be allowed in the public schools. By the conclusion of the rioting hundreds of people had been killed or injured and millions of dollars of property damage inflicted. Similar conflict — though not as physically destructive — occurred in many other American towns, with social strife largely only lessened when Catholics established their own school system.

- The Scopes “Monkey” Trial, a sensational case that grabbed the attention of the entire nation as a Tennessee court ruled whether or not it was acceptable to teach evolution in public schools. It is a topic that continues to rip communities apart today, and is so hot that, even where state standards mandate evolution be taught, most biology teachers avoid it. They simply don’t want to deal with the acrimony that would ensue.

- In 1974, Kanawha County, West Virginia, was plunged into a state of near-civil war over books selected by the county school district that many residents perceived to be anti-Christian and anti-American. Before the strife subsided commerce had ground to a halt, at least one person had been shot, and schools had been dynamited.

These are just some of the most well known or violent of the battles in the “interminable warfare” sparked not by private schooling, but the public schools Mann promised would bring peace if they became ascendant. Indeed, as I itemized in an analysis of just the 2005-06 school year, values-based skirmishes are fought all around us, all the time, whether over prayer in the schools, reading assignments, bullying and student speech, ethnic studies, and on and on. But that is exactly what we should expect when people of widely diverse religions, ethnicity, and philosophies are all required to support a single system of government schools. They won’t just give up the things that are often at the very heart of their lives — they will fight to have them taught.

Perhaps the biggest irony in all this is that students who attend private schools, even after adjusting for important non-school factors, are actually more knowledgeable about civics, active in their communities, and tolerant of others than are public school students. As University of Arkansas professor Patrick Wolf discovered in reviewing the empirical literature:

The statistical record suggests that private schooling and school choice often enhance the realization of the civic values that are central to a well-functioning democracy. This seems to be the case particularly among ethnic minorities (such as Latinos) in places with great ethnic diversity (such as New York City and Texas), and when Catholic schools are the schools of choice. Choice programs targeted to such constituencies seem to hold the greatest promise of enhancing the civic values of the next generation of American citizens.

How could this be? Because, in contrast to the assumption of Mann and others, most people don’t have to be forced to embrace tolerance and responsible freedom, they choose them. Public schooling, conversely, sends the message that government, not individuals freely working together, is responsible for whatever problems communities face. Even more importantly, by forcing diverse people together, government schools drop them into a zero-sum arena and render conflict all but inevitable.

Common schools haven’t brought us peace in our day. Indeed, quite the opposite.

The State of the Union on Stossel

Here’s an edited version of last night’s special “Stossel” show following the State of the Union Address. Our Cato tape editors have cut right to my opening one-one-one with Stossel, wherein I talk about Obama’s “blueprint” for America and my suggestion for a bumper sticker reading YES YOU DID. Later Matt Welch, Megan McArdle, and Gov. Gary Johnson join the discussion and take on issue of taxes, Iraq, the looming but mostly ignored entitlements crisis, outsourcing, and the president’s audacious claim that his $50 billion bailout of GM and Chrysler had been a good deal. Skip the commercials, watch it here:

Related Tags

SOPA and Skepticism

Over at Libertarianism.org I have a new blog post on the lesson the technology community should have learned from their campaign against SOPA.

Imagine you’re an expert in some field of technical knowledge. Your field impacts quite a lot of people but most of them don’t understand the details the way you do. One day, Congress proposes legislation called the Make Things Better Act, which, its sponsors say, will make things better.

But wait. The Act happens to deal with exactly the field you’re knowledgeable about. And you know what? It won’t make things better. In fact, it will make things far, far worse. Not only will it make things worse, but any benefits the legislation does create will accrue exclusively to a small but powerful interest group.

So you and your other technically-minded friends mobilize against the Make Things Better Act and, through coordination and outcry, succeed in killing it. Two days later, Congress proposes another piece of legislation called the It’s Good for the Children Act. Except this time the law deals with an area outside your expertise. If you applied the lesson learned from the Make Things Better Act, you might react to this new proposal with skepticism. After all, when you were in a position to evaluate what Congress was really up to, you discovered that it wasn’t working in the interests of the American public but, instead, of a tiny and powerful minority. Couldn’t it be possible the new bill is just be more of the same?

Most likely, though, based on the way people typically react in these situations, you won’t apply that lesson. Instead you’ll say, “Boy this new law is great because my favored political party wrote it and, well, it’s good for the children.”

Related Tags

Obama’s State of the Union Signals Grand Strategy Status Quo

It was clever, though a bit too opportunistic, for the president to begin and end his State of the Union address with references to Iraq, and the sacrifices of the troops. The war has been a disaster for the United States, and for the Iraqi people, of course. But the subject has always been a win-win for him. Whenever he talks about Iraq, it serves as a not-so-subtle reminder about who got us into this mess (i.e. not him).

Others might gripe about the president wrapping himself in the troops, and the flag (or, in the case of this speech, the troops’ flag). But Americans are rightly proud of our military, and there is nothing wrong with invoking the spirit of service and sacrifice that animates the members of our military. (There is something wrong with suggesting that all Americans should act as members of the military do, a point that Ben Friedman makes in a separate post.)

But while some degree of chest-thumping, “America, ooh-rah” is to be expected, this passage sent me over the edge:

America is back.

Anyone who tells you otherwise, anyone who tells you that America is in decline or that our influence has waned, doesn’t know what they’re talking about. …Yes, the world is changing; no, we can’t control every event. But America remains the one indispensable nation in world affairs – and as long as I’m President, I intend to keep it that way.

Have we learned nothing in the past decade? Have we learned anything? To say that we are the indispensable nation is to say that nothing in the world happens without the United States’ say so. That is demonstrably false.

Of course, the United States of American is an important nation, the most important, even. Yes, we are an exceptional nation. We boast an immensely powerful military, a still-dynamic economy (in spite of our recent challenges), and a vibrant political culture that hundreds of millions of people around the world would like to emulate. But the world is simply too vast, too complex, and the scale of transactions in the global economy is enormous. It is the height of arrogance and folly for any country to claim indispensability.

The president is hardly alone, however. Many in Washington—including some of his most vociferous critics in the Republican Party— celebrate the continuity in U.S. foreign policy as an affirmation of its wisdom. The president’s invocation of the “indispensable nation” line from the mid-1990s is merely the latest manifestation of a foreign policy consensus that has held for decades.

But the world has changed, and is still changing. Our grand strategy needs to adapt. When we embarked on the unipolar project after the end of the Cold War, the United States accounted for about a third of global economic output, and a third of global military expenditures; today, we account for just under half of global military spending, but our share of the global economy has fallen below 25 percent.

What we need, therefore, is a new strategy that aims to promote our core interests, but that doesn’t expect U.S. troops and taxpayers to also bear the burdens of promoting everyone else’s. After all, the values that are so important to most Americans, and that the president cited in his speech last night, are also cherished by hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of people in many countries around the world. It is reasonable to expect them to pay some of the costs required to advance these values, and to sustain a peaceful and prosperous international order. Our current strategy still presumes that it is not.

Related Tags

The Trouble with the State of the Union: America Is Not a Military Unit

At both the beginning and end of his state of the union address last night, the president suggested that the country can solve its problems by modeling itself after the military. Near the start he said:

At a time when too many of our institutions have let us down, [members of the military] exceed all expectations. They’re not consumed with personal ambition. They don’t obsess over their differences. They focus on the mission at hand. They work together. Imagine what we could accomplish if we followed their example.

He ended on the same note, comparing the unity of the Navy SEAL team that killed bin Laden to the political cooperation between himself Hillary Clinton and Robert Gates, and then suggested we all follow that example:

This Nation is great because we built it together. This Nation is great because we worked as a team. This Nation is great because we get each other’s backs. And if we hold fast to that truth, in this moment of trial, there is no challenge too great; no mission too hard. As long as we’re joined in common purpose, as long as we maintain our common resolve, our journey moves forward, our future is hopeful, and the state of our Union will always be strong.

One problem with this rhetoric is its militarism. Not content to thank the troops for serving, the president has adopted the notion that military culture is better than that of civilian society and ought to guide it. That idea, too often seen among service-members, is corrosive to civil-military relations. Troops should feel honored by their society, but not superior to it. We do not need to pretend they are superhuman to thank them.

There is an even bigger problem with this “be like the troops, put aside our differences, stop playing politics, salute and get things done for the common good” mentality. It is authoritarian. Sure, Americans share a government, much culture, and have mutual obligations. But that doesn’t make the United States anything like a military unit, which is designed for coordinated killing and destruction. Americans aren’t going to overcome their political differences by emulating commandos on a killing raid. And that’s a good thing. At least in times of peace, liberal countries should be free of a common purpose, which is anathema to freedom.

The more we get shoved together under a goal, the less free we are, and the more we have to fight about. Differing conceptions of good and how to achieve it are the source of our political disagreements. Those competing ends are manifest in different parties, congressional committees, executive agencies and policy programs. Our government is designed for fighting itself, not others.

There’s no danger that this suggestion that we emulate military cooperation to make policy will actually succeed. Our politicians are hypocritical enough to rarely believe their own rhetoric about escaping politics, thankfully. But the happy talk is at least a distraction from useful thought about successful legislating. Productive deals get done by recognizing and accommodating competing ends, not by wishing them away. That means better politics, not none.