My French is rusty, but I’m pretty sure the Fresh Prince just flipped out at the idea of a 75-percent marginal tax rate like that advocated by France’s new socialist president.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Looking at Austerity in Greece

Since 2009 Greece has been at the epicenter of the euro crisis, and after last week’s parliamentary election, it looks like its departure from the common currency is a matter of weeks. Everyone agrees that Greece didn’t get into trouble because it spent too little, just the opposite. When George Papandreou became prime minister in October 2009, he found that his conservative predecessor had cooked the books and left him with a staggering fiscal deficit of 12.7% of GDP. The socialist Papandreou was then forced to shelve his promises of more handouts and implement a program of fiscal austerity in exchange for multi-billion bailouts from the European Union.

Two and a half years on, things look as bleak as ever for Greece, with an economy that is still shrinking and unemployment on the rise. Today, many people claim that, even though profligacy was the source of Greece’s problems, austerity is now making things worse by cutting spending too fast too soon. Time magazine’s Fareed Zakaria explained the dynamics yesterday in his CNN show GPS:

“The problem is that as these governments cut spending in very depressed economies, it has caused growth to slow even further – you see government workers who have been fired tend to buy fewer goods and services, for example – and all this means falling tax receipts and thus even bigger deficits.”

Zakaria is not the only one describing austerity as mostly spending cuts, and some pundits even dramatize the term by adding adjectives such as “deep,” “brutal,” “savage,” or “self-defeating.” Let’s look at how brutal these spending cuts have been in Greece:

Source: Source: European Commission, Economic and Financial Affairs.

Spending has declined to approximately its 2007 level in nominal terms, while in real terms it actually continues to go up. (I look at spending in real terms because that’s what Ryan Avent at The Economist said we should look at in a reply to Veronique de Rugy’s initial graph on austerity in Europe. Note that, as in my previous posts on Britain and France, I’m using the GDP deflator to calculate spending in real terms). If we look at spending in real terms, there haven’t been any spending cuts in Greece. On the other hand, Tyler Cowen observes that “in the short run it is supposedly nominal which matters (that said, gdp and population [and inflation] are not skyrocketing in these countries for the most part).” Let’s look at nominal then. Since 2000, public spending rose in Greece at an annual rate of 7.8% until 2009. Then it declined by 8.3% in 2010 and a further 4.1% in 2011. This is certainly a cut in spending, but far from brutal.

Some argue that we shouldn’t look at spending levels when talking about austerity, but rather at spending as a share of the economy. In that sense, government spending in Greece went up from 47.1% of GDP in 2000 to 53.8% in 2009 and it has come down to 50.3% in 2011—approximately its 2008 level. However, I don’t buy the argument. Does it mean that the government has to spend an ever increasing share of the GDP in order to keep the economy afloat? Is half of the economy not enough when it comes to government spending?

What about Zakaria’s argument of the crippling effect of firing government workers on growth? Last January, The Economist looked at the situation in Greece and noted that “Of the 470,000 who have lost their jobs since 2008, not one came from the public sector. The civil service has had a 13.5% pay cut and some reductions in benefits, but no net job losses.” As for what “austerity” means for most Greeks, the magazine added, “Since Greece’s first bail-out in May 2010, the government has imposed austerity, increasing taxes so much that people can barely manage.”

The Economist is not alone in pointing out the extent to which taxes have gone up. Even the IMF has done so. Back in November, Poul Thomsen, the IMF mission chief in Greece, said that the country “has relied too much on taxes and I think one of the things we have seen in 2011 is that we have reached the limit of what can be achieved through increasing taxes.” Since then Greece agreed to eliminate 15,000 government jobs (2% of its public sector workforce) in exchange for a second bailout. Once again, that figure pales when compared to the number of people who have lost their jobs in the private sector.

The evidence shows that in Greece austerity has meant significant tax increases and timid spending cuts.

Related Tags

Social Security ‘Calculator’

One of the first things I did upon joining Cato in 2004 was to develop a Social Security benefit calculator. That work would later contribute to my book on the outcomes of different Social Security reform proposals.

The Social Security Administration used to have a benefit calculator on its website, but it was cumbersome to use. Now the SSA has a portal that enables you to view your personalized earnings and benefits information. This is in lieu of the paper statement that was recently suspended for those younger than age 60.

For the SSA calculator, you can register here (after answering some identifying questions) and look at the benefits that the system is promising to give you (lots)—and then compare them to what you really can expect to receive (not so much, and even less the younger you are).

Related Tags

No Thanks to Aid, Africa Is Getting Better

In spite of our humble efforts, the arguments concerning the efficacy of foreign aid go on. The aficionados of the debate are no doubt aware of the latest controversy involving Columbia University Professor Jeffrey Sachs’ Millennium Villages Project (MVP). In 2006, Sachs convinced wealthy donors – from the United Nations and the government of Japan to Goldman Sachs and Pepsico – to sponsor economic development in 14 villages in 10 African countries. If aid in those villages worked, Sachs theorized, the program could be scaled upwards and vindicate those who advocate in favor of large foreign aid transfers from wealthy countries to poor ones.

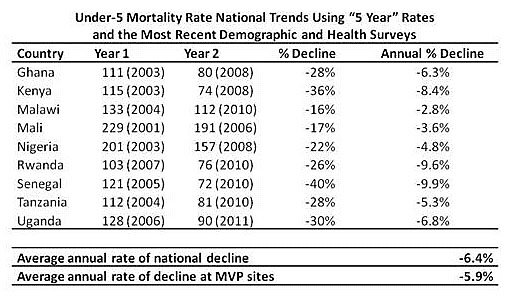

Unfortunately for Sachs, some of MVP’s previous claims about the beneficial effect of aid on human wellbeing in the millennium villages have been called into question. The latest installment in this saga involves the MVP’s claim that “the average rate of reduction of mortality in children younger than 5 years of age was three-times faster in Millennium Village sites than in the most recent 10-year national rural trends (7.8% vs. 2.6%).” World Bank research, however, found that “under‑5 mortality has fallen at just 5.9% per year at MVP sites, which is slower than the 6.4% average annual decline in under‑5 child mortality in the MVP countries nationwide.”

Whatever the actual decline in the Millennium villages, note the remarkable reduction in the mortality of children under the age of 5 (per 1000 live births) in selected African countries. As I noted elsewhere, Africa has just experienced a decade of robust economic growth fueled by economic reforms and high commodity prices. That, evidence suggests, may be better at explaining the fall in child mortality than foreign aid.

Adult Supervision

Some politicians say that banks need more regulation because JPMorgan Chase lost $2 billion, about 2 percent of its annual revenue.

Meanwhile, the federal government will have a deficit of about $1.3 trillion this year, more than half its annual revenue (and about a third of its annual spending).

Is there some sort of regulation that might remedy that?

Related Tags

Scott Walker and Public-Sector Unions

Today POLITICO Arena asks:

Did foes of Scott Walker make a bad bet on the recall?

My response:

We’ll know soon enough whether foes of Scott Walker made a bad bet on the recall, but either way, Wisconsin made a bad bet years ago in initiating America’s public-sector union movement.

The incentives thus established — with concentrated benefits for state employees and dispersed costs for taxpayers — have made it all too easy for politicians to cave in to union demands, resulting over time in government workers with benefits far exceeding anything a rational market would afford — or those who pay for the benefits (taxpayers) can afford. Not surprisingly, therefore, states with strong public-sector unions — California, Illinois, New York — are today in economic disarray.

Bad enough that private-sector unions make businesses less competitive, the remedy for which is moving to right-to-work states or abroad. States can’t move. But their businesses and citizens can — and they do. Witness California over the past decade, and New York for several decades. Scott Walker has done us all a favor by crystallizing the issues facing so many states today.

Related Tags

California Knows How to Party… $16 Billlion Too Lavishly

Californians may be forgiven for expectorating coffee over their morning newspapers today, as they learn that their state deficit is not $9 billion, as Governor Brown’s administration had predicted, but rather $16 billion. Oops.

Further increasing the breakfast table choking hazard is the Governor’s “solution”: raise taxes. Gov. Brown is pushing a fall ballot initiative that would raise both sales and income taxes. He argues that this is preferable to cutting spending on things like public schooling on the grounds that schools have already been slashed to the bone. But have they? Actually, no. California’s per pupil spending has nearly doubled over the past forty odd years, in real inflation-adjusted dollars, and remains near its all-time high.

What did California get for that massive spending increase? Not a great deal if the SAT performance of its college-bound high school students is any guide. And, as I pointed out in this op-ed, it’s a pretty reasonable guide.

But while raising taxes has consistently failed to improve educational performance, cutting them actually works—via tax-credit school choice programs that give families an easier choice between public and private schools. Florida’s education tax credit program, for instance, has been shown to improve the achievement of students who stay in public schools, to improve the achievement of students who accept scholarships and attend private schools, and to save taxpayers millions of dollars a year. If expanded on a mass scale in a large state like California, it would save billions of dollars a year.

So what’ll it be, Californians? Fiscal and education policy sobriety, or the Governor’s hair-of-the-dog continued big government partying?