The Senate Finance Committee’s ranking member is not amused.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Wide Off the Mark, or, Nonsense about NGDP Targeting

I meant to do so weeks ago, but I only just got around to reading the little flurry of posts concerning NGDP targeting that was set off by John Taylor’s critical remarks on the topic. And now, despite the delay, I can’t resist putting-in my own two cents, because it seems to me that much of the discussion misses the real point of targeting nominal spending, either entirely or in part; what’s more, some of the discussion is just-plain nonsense.

Thus Professor Taylor complains that, “if an inflation shock takes the price level and thus NGDP above the target NGDP path, then the Fed will have to take sharp tightening action which would cause real GDP to fall much more than with inflation targetting.” Now, first of all, while it is apparently sound “Economics One” to begin a chain of reasoning by imagining an “inflation shock,” it is crappy Economics 101 (or pick your own preferred intro class number), because a (positive) P or inflation “shock” must itself be the consequence of an underlying “shock” to either the demand for or the supply of goods. The implications of the “inflation shock” will differ, moreover, according to its underlying cause. If an adverse supply shock is to blame, then the positive “inflation shock” has as its counterpart a negative output shock. If, on the other hand, the “inflation shock” is caused by an increase in aggregate demand, then it will tend to involve an increase in real output. Try it by sketching AS and AD schedules on a cocktail napkin, and you will see what I mean.

Good. Now ask yourself, in light of the possibilities displayed on the napkin, what sense can we make of Taylor’s complaint? The answer is, no sense at all, for if the “inflation shock” is really an adverse supply shock, then there’s no reason to assume that it involves any change in NGDP. On the contrary: if you are inclined, as I am (and as Scott Sumner seems to be also) to draw your AD curve as a rectangular hyperbola, representing a particular level of Py (call it, if you are a stickler, a “Hicks-compensated” AD schedule), it follows logically that an exogenous AS shift by itself entails no change at all in Py, and hence no departure of Py from its targeted level. In this case, although real GDP must in fact decline, it will not decline “much more than with inflation targetting,” for the latter policy must involve a reduction in aggregate spending sufficient to keep prices from rising despite the collapse of aggregate supply. A smaller decline in real output could, on the other hand, be achieved only by expanding spending enough to lure the economy upwards along a sloping short-run AS schedule, that is, by forcing real GDP temporarily above its long-run or natural rate–something, I strongly suspect, Professor Taylor would not wish to do.

If, on the other hand, “inflation shock” is intended to refer to the consequence of a positive shock to aggregate demand, then the “shock” can only happen because the central bank has departed from its NGDP target. Obviously this possibility can’t be regarded as an argument against having such a target in the first place! (Alternatively, if it could be so regarded, one could with equal justice complain that similar “inflation shocks” would serve equally to undermine inflation targeting itself.)*

But lurking below the surface of Professor Taylor’s nonsensical critique is, I sense, a more fundamental problem, consisting of his implicit treatment of stabilization of aggregate demand or spending, not as a desirable end in itself, but as a rough-and-ready (if not seriously flawed) means by which the Fed might attempt to fulfill its so-called dual mandate–a mandate calling for it to concern itself with both the control of inflation and the stability of employment and real output. And this deeper misunderstanding is, I fear, one of which even some proponents of NGDP targeting occasionally appear guilty. Thus Scott Sumner himself, in responding to Taylor, observes that “the dual mandate embedded in NGDP targeting is not that different from the dual mandate embedded in the Taylor Rule,” while Ben McCallum, in his own recent defense of NGDP targeting, treats it merely as “one way of taking into account both inflation and real output considerations.”

To which the sorely needed response is: no; No; and NO.

We should not wish to see spending stabilized as a rough-and-ready means for “getting at” stability of P or stability of y or stability of some weighted average of P and y: we should wish to see it stabilized because such stability is itself the very desideratum of responsible monetary policy. The belief, on the other hand, that stability of either P or y is a desirable objective in itself is perhaps the most mischievous of all the false beliefs that infect modern macroeconomics. Some y fluctuations are “natural,” in the sense meaning that even the most perfect of perfect-information economies would be wise to tolerate them rather than attempt to employ monetary policy to smooth them over. Nature may not leap; but it most certainly bounces. Likewise, some movements in P, where “P” is in practice heavily weighted in favor, if not comprised fully, of prices of final goods, themselves constitute the most efficient of conceivable ways to convey information concerning changes in general economic productivity, that is, in the relative values of inputs and outputs. A central bank that stabilizes the CPI in the face of aggregate productivity innovations is one that destabilizes an index of factor prices.

We shall have no real progress in monetary policy until monetary economists realize that, although it is true that unsound monetary policy tends to contribute to undesirable and unnecessary fluctuations in prices and output, it does not follow that the soundest conceivable policy is one that eliminates such fluctuations altogether. The goal of monetary policy ought, rather, to be that of avoiding unnatural fluctuations in output–that is, departures of output from its full-information level–while refraining from interfering with fluctuations that are “natural.” That means having a single mandate only, where that mandate calls for the central bank to keep spending stable, and then tolerate as optimal, if it does not actually welcome, those changes in P and y that occur despite that stability.

*Over at TheMoneyIllusion Bob Murphy remarks that this part of my criticism of Taylor is “too glib.” He’s right: central bankers can’t be faulted for failing to abide by a rule when that failure stems from their having failed to anticipate what is, after all, a “shock” to demand. But the main point of this part of my criticism is simply that, understood as referring to the consequences of an AD shock, Taylor’s criticism is, not a criticism of NGDP targeting as such, but a criticism of any sort of nominal level targeting that doesn’t allow “bygones to be bygones” when it comes to shock-based departures from the level target (12–1‑2011).

Related Tags

A Weak Defense of an Illegal Fix to an ObamaCare Glitch

In this November 16 op-ed, Jonathan Adler and I explain how the Obama administration is trying to save ObamaCare (“the Affordable Care Act”) by creating tax credits and government outlays that Congress hasn’t authorized. (The administration describes this “premium assistance” solely as tax credits.) This week, the administration tried to reassure everybody that no, they’re not doing anything illegal.

Here’s how IRS commissioner Douglas H. Shulman responded to a letter from two dozen members of Congress (emphasis added):

The statute includes language that indicates that individuals are eligible for tax credits whether they are enrolled through a State-based Exchange or a Federally-facilitated Exchange. Additionally, neither the Congressional Budget Office score nor the Joint Committee on Taxation technical explanation of the Affordable Care Act discusses excluding those enrolled through a Federally-facilitated Exchange.

And here is how HHS tried to dismiss the issue (emphasis added):

The proposed regulations issued by the Treasury Department, and the related proposed regulations issued by the Department of Health and Human Services, are clear on this point and supported by the statute. Individuals enrolled in coverage through either a State-based Exchange or a Federally-facilitated Exchange may be eligible for tax credits. …Additionally, neither the Congressional Budget Office score nor the Joint Committee on Taxation technical explanation discussed limiting the credit to those enrolled through a State-based Exchange.

These statements show that the administration’s case is weak, and they know it.

When government agencies say that a statute indicates they are allowed to do X, or that their actions are supported by that statute, it’s a clear sign that the statute does not explicitly authorize them to do what they’re trying to do. If it did, they would say so. (A Treasury Department spokeswoman offers a similarly worded rationale.)

In our op-ed, Adler and I explain why the statutory language to which these agencies refer does not create the sort of ambiguity that might enable the IRS to get away with offering premium assistance in federal Exchanges anyway. (Nor does the fact that the CBO and the JCT misread portions of this 2,000-page law create such ambiguity.) That’s because there is no ambiguity in that language. There is only a desperate search for ambiguity because the law clearly says what supporters don’t want it to say.

Finally, the fact that these two statements are so similar shows that the administration considers this glitch to be a serious problem and wants everyone on the same page.

Washington & Lee University law professor Timothy Jost is an ObamaCare supporter and a leading expert on the law. He is also too honest for government service, for he has acknowledged that ObamaCare “clearly” does not authorize premium assistance in federal Exchanges, and that it is only “arguabl[e]” that federal courts will let the administration get away with offering it. (Again, in our op-ed, Adler and I explain why that argument falls flat.)

After reading the administration’s statements, Adler writes, “If that’s all they got, they should be worried.”

Republicans Take an Ax to Government

We hear a lot these days about Republicans cutting, slashing, dismantling government. The latest ax-wielder is Virginia governor Robert McDonnell, an oft-mentioned candidate for vice president. Here’s what the Washington Post reports under the (paper) headline “McDonnell looks to shrink government”:

Gov. Robert F. McDonnell announced Tuesday that he is recommending eliminating two state agencies, cutting 19 boards and commissions and de-regulating three professions.

It’s part of his ongoing effort to reshape and shrink state government — one of his signature campaign promises.

McDonnell (R) made the recommendations to the General Assembly. The Department of Planning and Budget estimates the proposals will save at least $2 million per year.

Two million dollars. Two million dollars. That’s what the Washington Post sees as “shrinking government.” I’m guessing the Post doesn’t often run a story when a governor does something that “expands government” by $2 million.

But Virginia has a reputation for fiscal conservatism. Maybe $2 million is actually a big chunk of the state’s budget. Let’s check the numbers. As it turns out, this week the National Governors Association and the National Association of State Budget Officers put out a report on state finances, and it showed that Virginia’s general fund spending is up 7.1 percent in 2012. And according to Virginia’s own budget, that’s an increase of $1.1 billion in FY2012. That’s not the whole budget, by the way. In addition to the $16 billion in General Fund spending, Virginia will also spend $23 billion in FY2012. So let’s review:

Total Virginia spending FY2012 $39,600,000,000

General Fund spending 16,500,000,000

General Fund spending increase 1,100,000,000

McDonnell’s shrink-government savings 2,000,000

So I guess the total increase in Virginia spending in 2012 won’t be $1,100,000,000, it’ll be $1,098,000,000 — if the legislature approves McDonnell’s recommendations. And of course we certainly can’t be sure that the legislature will approve such recommendations as deregulating interior design and eliminating such vital boards as the Commonwealth Competition Council, the Interagency Dispute Resolution Council, the Virginia Public Buildings Board, the Virginia Council on Human Resources, the Small Business Advisory Board, and more.

Related Tags

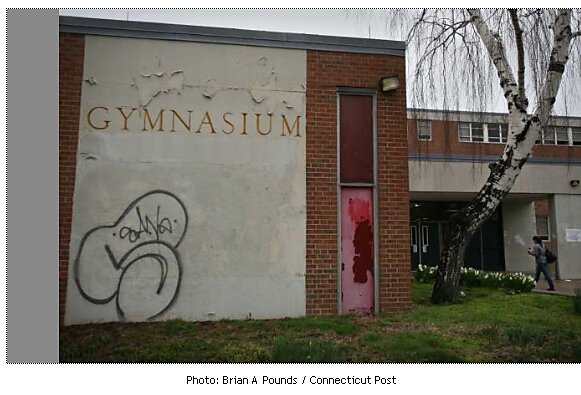

Why Public Schools Crumble, and Why Another $30 Billion Won’t Change That

The Congressional Quarterly reports that Senate Democrats are pushing another $30 billion bailout—this time for public school buildings. By all accounts, many of those buildings are indeed sinking into decrepitude. But as I discovered a couple of years back, public schools are already spending 50% more per pupil than private schools that do manage to maintain their buildings. So what’s the real problem?

The answer comes from one of the federal government’s own assessments of school facilities nationwide. According to that report,

a decisive cause of the deterioration of public school buildings was public school districts’ decisions to defer maintenance and repair expenditures from year to year.… [And] deferred maintenance increases the cost of maintaining school facilities; it speeds up the deterioration of buildings and the need to replace equipment. [p. 3–4]

This is why we can’t have nice things: public school officials don’t take care of them. They already have far more money to spend than administrators of well-maintained private schools, so giving them yet more money won’t fix their problems. Perhaps Senate Democrats are not ignorant of these facts, and are merely proposing this new bailout in an attempt to make Republicans look bad for opposing a tax hike on the rich. Neither possibility shows the Democrats in a particularly favorable light.

Related Tags

Jury Nullification and Free Speech

Federal prosecutors are pressing their case against Julian Heicklen, the elderly man who distributed pamphlets about jury nullification. A lot of things are said about jury nullification and much of it is inaccurate. But whatever one’s view happens to be on that subject, I would have thought that the idea of talking about (and that includes advocating) jury nullification would be a fairly simple matter of free speech. We now know that the feds see the matter very differently. (FWIW, my own view is that in criminal cases jury nullification is part and parcel of what a jury trial is all about.)

In response to Julian Heicklen’s motion to dismiss his indictment on First Amendment grounds, federal attorneys have filed a response with the court. Here is the federal government’s position: “[T]he defendant’s advocacy of jury nullification, directed as it is to jurors, would be both criminal and without Constitutional protections no matter where it occurred” [emphasis added]. This is really astonishing. A talk radio host is subject to arrest for saying something like, “Let me tell you all what I think. Jurors should vote their conscience!” Newspaper columnists and bloggers subject to arrest too?

If Heicklen had been distributing flyers that said, “I Love Prosecutors. Criminals Have No Rights!” there would not have been any “investigation” and tape recording from an undercover agent. Any complaint lodged by a public defender would have been scoffed at.

First Amendment experts will know more than I about the significance of the “plaza” outside the courthouse and whether or not that’s a public forum under Supreme Court precedents. The feds make much of the fact that the plaza is government property. Well, so is the Washington mall, but protesters have been seen there from time to time. The plaza, however, is not the key issue. Activists like Heicklen would simply move 10–20 yards further away (whatever the situation may be) and the prosecutors seem determined to harass them all the way back into their homes, and even there if they blog, send an email, post a comment on a web site, text, tweet, or use a phone to communicate with others. After all, so many people are potential jurors.

Judges and prosecutors already take steps to exclude persons who know about jury nullification from actual service. And the standard set of jury instructions says that jurors must “apply the law in the case whether they like it or not.” But the prosecution of Heicklen shows that the government wants to expand its power far beyond the courthouse and outlaw pamphleteering and speech on a controversial subject. Once again the government is trying to go over, around, and right through the Constitution.

For previous coverage and additional info, go here, here, and here.

One Executive Order That Could Stop ObamaCare

A new memo from the Congressional Research Service explains that the next president cannot simply stop ObamaCare (“PPACA”) by executive order:

[A] president would not appear to be able to issue an executive order halting statutorily required programs or mandatory appropriations for a new grant or other program in PPACA, and there are a variety of different types of these programs. Such an executive order would likely conflict with an explicit congressional mandate and be viewed “incompatible with the express…will of Congress”…However, there may be instances where PPACA leaves discretion to the Secretary to take actions to implement a mandatory program, and…an executive order directing the Secretary to take particular actions may be analyzed as within or beyond the President’s powers to provide for the direction of the executive branch.

In other words, the worst elements of ObamaCare — the government price controls it imposes on health insurance, the individual mandate, and the new spending on health-insurance entitlements — are “statutorily required programs” that, say, President Romney cannot repeal or even halt by executive order.

However, there is one executive order that could effectively block ObamaCare, and that lies well within the president’s powers.

The Obama administration has issued a proposed IRS rule that would offer “premium assistance” (a hybrid of tax credits and outlays) in health insurance “exchanges” created by the federal government. The only problem is, ObamaCare only authorizes these tax credits and outlays in “an Exchange established by the State.” The administration did so because without premium assistance, ObamaCare will collapse, at least in states that do not create their own Exchanges. Yet the executive branch does not have the power to create new tax credits and outlays. Only Congress does. So if the final version of this IRS rule offers premium assistance in federal Exchanges, it will clearly exceed the authority that Congress and the Constitution have delegated to the executive branch.

In that case, the next president could issue an executive order directing the IRS either not to offer premium assistance in federal Exchanges or to rescind this rule and draft a new one that does not. The U.S. Constitution demands that the president “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Such an executive order therefore lies clearly within the president’s constitutional powers: it would ensure the faithful execution of the laws by preventing the executive from usurping Congress’ legislative powers.

While such an executive order would not repeal ObamaCare, as Jonathan Adler and I explain in this Wall Street Journal oped, it would “block much of ObamaCare’s spending and practically force Congress to reopen the law.”