For most goods and services, governments leave the production, distribution, sale, and consumption decisions to private individuals or groups.

For gambling, however, US states are schizophrenic. Historically, state governments banned gambling of all kinds. In 1931, however, Nevada re-legalized casinos, leading to the return of parimutuel horse betting and casinos in some states. In 1964, New Hampshire authorized the first state-run lottery, and 44 more states eventually followed suit. Following the 2018 Supreme Court ruling in Murphy v. NCAA, 38 states legalized sports betting.

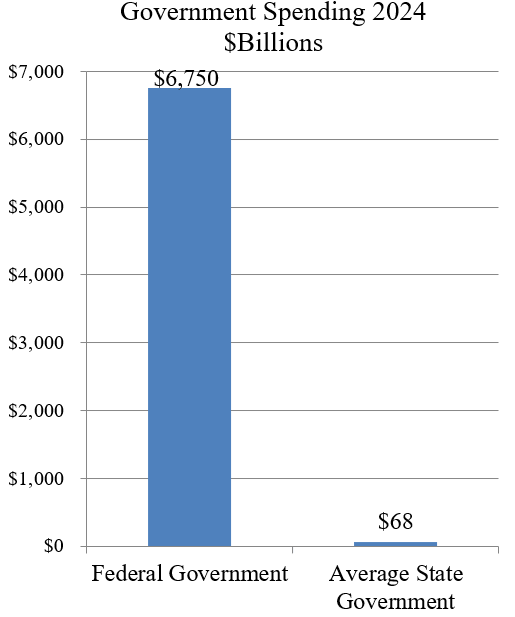

Thus many kinds of gambling are now legal (casinos, sports betting, horse races, and more), yet private lotteries are not legal in the United States. Some states have transferred day-to-day operations to private companies. But these lotteries are still under government control, and private companies cannot enter the market. The government profits off this monopoly, raising $24.4 billion of revenue from the 49 percent of Americans who participate.

The inconsistent treatment makes no sense; the right policy is for governments to impose no limits on the private provision of gambling activities, while itself exiting the gambling business.

The argument for legalization is standard: prohibition drives markets underground, leading to violence and other adverse effects. For example, when gambling was illegal in New York in the 1920s, the practice remained widespread in underground markets.

The argument against government provision of lotteries is also standard: government provision addresses no plausible externality or market failure; if anything, it encourages participation in an activity that some regard as immoral or addictive. Libertarians discount this last risk, but they still argue against government provision.

The argument that lotteries raise revenue is misguided. Operating lotteries seems like a “free” way to raise revenue because participants choose to buy lottery tickets. But governments can tax private gambling in the same way as any other activity.

This article appeared on Substack on November 22, 2024. Amelia Heller, a student at Harvard College, co-wrote this post.