As President Obama counts down the days of his last year in office, one positive step he could take for his legacy would be to halt the federal government’s use of civil asset forfeiture and make the suspension of the equitable sharing program permanent.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

On the Bright Side: The Effects of Elevated CO2 on Two Coffee Cultivars

Compliments of rising atmospheric CO2, in the future you can have a larger cup of coffee and drink it too!

In the global market, coffee is one of the most heavily traded commodities, where more than 80 million people are involved in its cultivation, processing, transportation and marketing (Santos et al., 2015). Cultivated in over 70 countries, retail sales are estimated at $90 billion USD. Given such agricultural prominence, it is therefore somewhat surprising, in the words of Ghini et al. (2015) that “there is virtually no information about the effects of rising atmospheric CO2 on field-grown coffee trees.” Rather, there exists only a few modeling studies that estimate a future in which coffee plants suffer (1) severe yield losses (Gay et al., 2006), (2) a reduction in suitable growing area (Zullo et al., 2011), (3) extinction of certain wild populations (Davis et al., 2012) and (4) increased damage from herbivore, pathogen and pest attacks (Ghini et al., 2011; 2012; Jaramillo et al., 2011; Kutywayo et al., 2013), all in consequence of predicted changes in climate due to rising atmospheric CO2.

In an effort to assess such speculative model-based predictions, the ten-member scientific team of Ghini et al. set out to conduct an experiment to observationally determine the response of two coffee cultivars to elevated levels of atmospheric CO2 in the first Free-air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) facility in Latin America. Small specimens (3–4 pairs of leaves) of two coffee cultivars, Catuaí and Obatã, were sown in the field under ambient (~390 ppm) and enriched (~550 ppm) CO2 conditions in August of 2011 and allowed to grow under normal cultural growing conditions without supplemental irrigation for a period of 2 years.

No significant effect of CO2 was observed on the growth parameters during the first year. However, during the growing season of year 2, net photosynthesis increased by 40% (see Figure 1a) and plant water use efficiency by approximately 60% (Figure 1b), regardless of cultivar. During the winter, when growth was limited, daily mean net photosynthesis “averaged 56% higher in the plants treated with CO2 than in their untreated counterparts” (Figure 1c). Water use efficiency in winter was also significantly higher (62% for Catuaí and 85% for Obatã, see Figure 1d). Such beneficial impacts resulted in significant CO2-induced increases in plant height (7.4% for Catuaí and 9.7% for Obatã), stem diameter (9.5% for Catuaí and 13.4% for Obatã) and harvestable yield (14.6% for Catuaí and 12.0% for Obatã) over the course of year 2. Furthermore, Ghini et al. report that the increased crop yield “was associated with an increased number of fruits per branch, with no differences in fruit weight.”

Figure 1. Effect of ambient (390 ppm) and elevated (550 ppm) CO2 concentration on two coffee cultivars, Catuaí (CAT) and Obatã (OBA), growing in a FACE construct: (Panel A, top left) net CO2 assimilation rate (A) during the growing season, (Panel B, bottom left) net CO2 assimilation rate during the winter, (Panel C, top right) water use efficiency (WUE), defined as internal-to-ambient CO2 concentration ratio (Ci/Ca, during the growing season, (Panel D, bottom right) water use efficiency during the winter. Adapted from Ghini et al. (2015).

Some have hypothesized that increasing plant matter associated with elevated CO2 would contain less protein, but with respect to leaf nitrogen content (a marker for protein content), the authors report it was “within an expected range for coffee” for both cultivars at both CO2 concentrations, “implying that no apparent N deficiency was observed in this study.” Ghini et al. were also able to examine the combined impact of elevated CO2 and plant damage from pests and disease. Here, they found that “under elevated CO2 reduced incidence of leaf miners (Leucoptera coffeela) occurred on both cultivars during periods of high infestation.” In addition, they report there was no significant effect of CO2 treatment on disease incidence of rust (Hemileia vastatrix) and Cercospora leaf spot (Cercospora coffeicola); and fungal communities associated with mycotoxins was not affected either.

All in all, it is quite clear that this observational assessment of the impacts of rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations on coffee plants is quite different from that derived from model-based analyses. And because observations always trump projections, those who cultivate, process, transport, market, and drink coffee now have a much more optimistic future to look forward to, a world in which coffee plants will benefit from this ever-benevolent aerial fertilizer!

References

Davis, A.P., Gole, T.W., Baena, S. and Moat, J. 2012. The impact of climate change on indigenous arabica coffee (Coffea arabica): predicting future trends and identifying priorities. PLoS ONE 7: e47981.

Gay, C., Estrada, C.G., Conde, C., Eakin, H. and Villers, L. 2006. Potential impacts of climate change on agriculture: a case of study of coffee production in Veracruz, Mexico. Climatic Change 79: 259–288.

Ghini, R., Bettiol, W. and Hamada, E. 2011. Diseases in tropical and plantation crops as affected by climate changes: current knowledge and perspectives. Plant Pathology 60: 122–132.

Ghini, R., Hamada, E., Angelotti, F., Costa, L.B. and Bettiol, W. 2012. Research approaches, adaptation strategies, and knowledge gaps concerning the impacts of climate change on plant diseases. Tropical Plant Pathology 37: 5–24.

Ghini, R., Torre-Neto, A., Dentzien, A.F.M., Guerreiro-Filho, O., Iost, R., Patrício, F.R.A., Prado, J.S.M., Thomaziello, R.A., Bettiol, W. and DaMatta, F.M. 2015. Coffee growth, pest and yield responses to free-air CO2 enrichment. Climatic Change 132: 307–320.

Jaramillo, J., Muchugu, E., Vega, F.E., Davis, A., Borgemeister, C. and Chabi-Olaye, A. 2011. Some like it hot: the influence and implications of climate change on coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) and coffee production in East Africa. PLoS ONE 6: e24528.

Kutywayo, D., Chemura, A., Kusena, W., Chidoko, P. and Mahoya, C. 2013. The impact of climate change on the potential distribution of agricultural pests: the case of the coffee white stem borer (Monochamus leuconotus P.) in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 8: e73432.

Santos, C.A.F., Leitão, A.E., Pais, I.P., Lidon, F.C. and Ramalho, J.C. 2015. Perspectives on the potential impacts of climate changes on coffee plant and bean quality. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 27: 152–163.

Zullo, J., Jr., Pinto, H.S., Assad, E.D., de Ávila, A.M.H. 2011. Potential for growing arabica coffee in the extreme south of Brazil in a warmer world. Climatic Change 109: 535–548.

Related Tags

One Sentence, or, Unpacking the Truth about the Founding of the Bank of France

When, in my days as a professor, I occasionally assigned term papers, I used to smile when students wondered out loud how they could possibly come up with enough to say to fill a whole 20 (or 15, or 5, or whatever) pages. After all, the problem, once you got to be where I was, wasn’t having too much space: it was not having space enough to say what needed saying. It was all I could do sometimes to squeeze my ideas into the 25 double-spaced typescript page-limit that prevailed among scholarly economics journals.

These days I’m no longer compelled to wrestle with academic journal editors, thank goodness. But I still face strict length limits now and then, like the one I’m confronting as I finally get around to writing my long-overdue review of Roger Lowenstein’s America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. I’m supposed to limit the review to 1000 words. Yet I could easily write 20,000 words about that book. In fact I have written 20,000, and then some, in the shape of a Cato Policy Analysis called “New York’s Bank: the National Monetary Commission and the Founding of the Fed.” Our respective titles give you some idea of where Lowenstein and I differ. Anyway, the PA isn’t ready yet. When it is, probably about a month from now, I will let you know.

Despite that PAs length, it also leaves much unsaid. It says nothing at all, for example, about the seemingly innocuous sentence in chapter five of America’s Bank that reads: “The Bank of France was chartered in 1800 as an antidote to the financial turmoil of the French Revolution.”

It is but a passing statement, in a work concerning the founding, not of the Bank of France, but of the Fed; and it is of no importance to that work’s thesis. And yet…and yet that sentence says plenty, for it represents as well as any sentence in Lowenstein’s book its author’s inclination — a very common one, to be sure — to view even the earliest central banks as sources of financial order and stability, despite the fact that doing so often means overlooking oodles of inconvenient facts.

In the case of the Bank of France, many of these inconvenient facts are, ironically enough, unabashedly set down in one of the volumes published by the National Monetary Commission — volumes that supposedly informed the Aldrich Plan and, indirectly, the Federal Reserve Act. These volumes generally display a bias in favor of central banking, as their sponsors intended them to do. Were one looking for a rose-colored portrayal of the Bank of France’s origins, one might expect to find it here.

Nevertheless, according to this particular volume’s author, André Liesse, the Bank of France was conceived, not as a remedy for France’s post-revolutionary financial turmoil, but as one for Napoleon’s fiscal difficulties. What’s more, far from having represented an improvement upon the status quo ante, its establishment marked the end of a remarkable though short-lived period of relative financial stability.

The disastrous failure, in 1721, of John Law’s Banque Royale, was, according to Liesse, entirely attributable to that bank’s involvement with the financial operations of the French government, and to its having secured, in return for that involvement, an exclusive right to issue banknotes. No wonder the bank’s failure resulted in an edict establishing complete freedom of note issue. Still, it was not until 1776 that the scars left by its collapse had healed sufficiently for another bank of issue to be established.

The new bank, the first Caisse d’Escompte, also ran into trouble as a result of “repeated state loans and government interference,” eventually leading to its becoming “nothing more than a branch of the public administration of finance.” The episode led the great economist (and Inspector General to Louis XVI) Du Pont de Nemours, in Liesse’s words,

to defend the true principles of banks of issue, asserting that a bank without a privilege, not involved in business relations with a debt-ridden and needy State, without the prerogative of forced currency, can not do otherwise than pay in coin on demand the value of every note issued.

In 1793 what remained of the Caisse d’Escompte succumbed to the financial “paroxysms” of the Revolution. Once again, according to Liesse, an institution that “would have been of real service to commerce if it had not allowed itself to become the State’s banker” instead found itself “lending money to the State without sufficient security, and receiving nothing in return but privileges which could not fail to be disastrous to it.”

But other banks of issue founded during the first Caisse d’Escompte’s lifetime managed to keep going despite the Revolutionary turmoil, including the “dangerous and ruinous flood of assignats” that was eventually to result in hyperinflation. Their owners and managers, mostly Protestants whose families had fled to France after the Edict of Nantes was revoked, had managed, “even in dealing with Napoleon,” to avoid being “cajoled into granting the State favors of credit which would cost them dear.” Their banks would soon be joined by other private institutions, including the Caisse des Comptes Courants, a central clearinghouse and bankers’ bank (it issued only very large denomination notes, meant for interbank settlements) established in Paris in 1796, and the Caisse d’Escompte du Commerce (or Caisse du Commerce, for short) — organized in 1797.

Thus began a brief but at least relatively glorious free banking interval.[1] “It can not be denied,” Liesse observes,

that after the terrible years of the Revolution, in the midst of the confusion and anarchy of the Directory, these credit establishments, in spite of difficult conditions, survived, maintained their credit, and were of real services to the commerce and bankers of Paris. They gave not the slightest occasion for complaint or interference on the part of the public authorities. Without any sort of privilege, having no connection with the Government, they were able to meet their obligations even in the midst of serious panics.

In short, freedom in banking worked just as Du Pont DeNemours said it would.[2]

Yet this success was not allowed to last. As Charles Conant puts it (History of Modern Banks of Issue, p. 44), the established banks

were doing an active and safe banking business when a new turn was given to the economic history of France by the coup d’état of the Eighteenth Brumaire (November 9, 1799), which made Napoleon Bonaparte First Consul and virtually supreme ruler of France.

Napoleon did not hesitate, despite the lessons of the past, to make plans for yet another government-controlled and privileged bank of issue, the Bank of France. For Liesse this development, far from seeming perfectly sensible (as modern central bank enthusiasts would have it), was astonishing. How could it happen, he wonders,

that this most satisfactory state of freedom came to an end and that in the course of a few years there was organized in Paris a bank with the exclusive privilege of issue? Is it due to a series of natural causes? No. Not one of the Caisses just described had occasioned disaster or invited suppression.[3] The new state of things came from the idea of credit which existed in the mind of General Bonaparte, as well as from his tendency to centralize everything, and because the government at the moment was in great need of money.

The “idea of credit which existed in the mind of General Bonaparte” boiled down to this: that he might have all the credit he wanted, if only he could establish a bank he could control, and award it a monopoly of currency extending throughout all of France.

At very least, Napoleon could have a lot more credit for a lot less than France’s then-existing banks were either willing, or even able, to supply. According to notes left by a member of Napoleon’s Council of State, to which Professor Liesse refers, the First Consul had “determined to lower” the interest rate at which the government could borrow to something less than the rate of 3 percent permonth banks were then demanding, thanks to the government’s poor credit. Napoleon “could not get what he wanted from the free banks. On the other hand, he felt that the Treasury needed money, and wanted to have under his hand an establishment which he could compel to meet his wishes. …It would certainly seem that here originated the idea of creating a new bank of issue.”

Given the circumstances, raising capital for the new bank was no easy proposition. To address that difficulty, the government first persuaded the Caisse des Comptes Courants to merge with it. To make further shares attractive, the new bank secured the privilege of holding various government deposits. Still, less than 7500 of a requisite 15,000 shares (half of the Bank’s stipulated capital stock) were taken, with Bonaparte’s friends and relatives having pride of place among the subscribers. (Napoleon himself was the Bank’s first subscriber, with 30 shares.) Further privileges were duly awarded it, until they sufficed to allow the remaining shares to be disposed of.

At first, the Bank of France had to compete with other banks of issue, including the Caisse du Commerce. When attempts to persuade the older bank to merge with the Bank of France failed, and especially after the Caisse du Commerce refused the government a loan it sought, Napoleon resorted to coercion. The details remain obscure. According to one account (admittedly in an English newspaper) at first the Bank of France, with Napoleon’s support, tried to bring its rival to submission by staging note-redemption raids. When that strategy failed, Napoleon simply had some of his troops shut the bank down. What’s certain is that the law of 24 Germinal, An XI (April 14, 1803), against which the Caisse du Commerce protested vehemently, awarded the Bank of France the exclusive right to issue banknotes in Paris, compelling all other banks of issue to surrender their assets to it.

“The Bank of France was chartered in 1800 as an antidote to the financial turmoil of the French Revolution.” It is one of those sentences that exposes a dominating — but distorted — worldview no less effectively than it obscures aspects of reality itself.

__________________________

[1]This was, in fact, the second such interval in French banking history. The first was still a still briefer episode, lasting only from 1790 to 1793, during which hundreds of “caisses patriotiques” flourished. According to Eugene White, that episode also “provides evidence of the success of free banking.” It ended when the government closed down the caisses in November 1793. See Eugene N. White, “Free Banking during the French Revolution,” Explorations in Economic History 27 (1990): 251–276.

[2]For a more recent, but equally favorable, assessment of France’s 1796–1803 free banking episode, see Philippe Nataf, “Free banking in France,” in Kevin Dowd, ed., The Experience of Free Banking (London: Routledge, 1992), pp. 123–36.

[3]Nor did suppressing inflation have anything to do with it. The raging inflation brought about by the Revolutionary government’s overissuance of assignats had come to a sudden end when, on July 16, 1796, the National Assembly decreed that people might conduct business using whatever money they chose, while allowing mandates, which had superseded assignats, to be accepted at their current value in specie. From that moment on, France was effectively back on a metallic standard.

Related Tags

Persuading China to Cooperate against North Korea

Another North Korean nuclear test, another round of demands that China bring Pyongyang to heel. Said Secretary of State John Kerry: Beijing’s policy “has not worked and we cannot continue business as usual.” Alas, his approach will encourage the PRC to dismiss Washington’s wishes.

The People’s Republic of China joined Washington in criticizing the latest blast. The PRC is the most important investor in and provides substantial energy and food assistance to the North. Beijing also has protected the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea by weakening past UN sanctions and enforcing those imposed with less than due diligence. If only China would get tough, runs the argument, the Kim Jong-un regime in Pyongyang would have to give way.

Alas, Chinese intervention is not the panacea many appear to believe. Contra common belief in Washington, the U.S. cannot dictate to the PRC. Threats are only likely to make the Chinese leadership more recalcitrant.

In fact, Beijing’s reluctance to wreck the North Korean state is understandable. If the administration wants to enlist China’s aid, it must convince Beijing that acting is in China’s, not America’s, best interest.

While unpredictable, obstinate, and irritating, so far the DPRK is not a major problem for China. The North disrupts American regional dominance and forces Seoul and Washington to beg for assistance in dealing with the DPRK. Even Pyongyang’s growing nuclear arsenal poses no obvious threat to China.

Why, then, should the PRC sacrifice its political influence and economic interests? A Chinese cut-off of energy and food would cause great hardship in the North. But a half million or more people died of starvation during the late 1990s without any change in DPRK policy.

Thus, the DPRK leadership may refuse to bend. The result might be a return to the 1990s, with a horrific collapse in living conditions but regime survival—and continued development of nuclear weapons.

Or the North Korean regime might collapse, with the possibility of violent conflict, social chaos, loose nukes, and mass refugee flows. The PRC might feel forced to intervene militarily to stabilize the North.

Moreover, in a united Republic of Korea China’s political influence would ebb. PRC business investments would be swept away. Worse, a reunited Korea allied with America would put U.S. troops on China’s border and aid Washington’s ill-disguised attempt at military containment.

Overall, then, sanctioning the North appears to create enormous benefits for Beijing’s rivals but few advantages for China.

Washington must make a compelling case to the PRC. The U.S. should begin by pointing out how unstable the current situation is, with an unpredictable, uncontrollable regime dedicated to creating a nuclear arsenal of undetermined size.

At the same time, the U.S., along with the ROK and Japan, should put together a serious offer for the North in return for denuclearization. The PRC has repeatedly insisted that America’s hostile policy underlies the DPRK nuclear program. Beijing responded acerbically to Washington’s latest criticism: “The key to solving the problem is not China.”

As I point out in National Interest: “Washington and its allies should offer a peace treaty, diplomatic recognition, membership in international organizations, the end of economic sanctions, suspension of joint military exercises, and discussions over ending America’s troop presence. This should be presented to the PRC with a request for the latter’s backing.”

At the same time, the U.S., South Korea, and Tokyo should promise to share the cost of caring for North Koreans and restoring order in the case of regime collapse. The U.S. and South should indicate their willingness to accept temporary Chinese military intervention in the event of bloody chaos.

The ROK should promise to respect Beijing’s economic interests while pointing to the far greater opportunities that would exist in a unified Korea. Finally, Washington should pledge to withdraw U.S. troops in the event of unification.

Getting Beijing’s cooperation still would be a long-shot. But the effort is worth a try. The U.S. and its allies have run out of options to forestall a nuclear North Korea.

Related Tags

Will China Accept Taiwan’s Political Revolution?

In one of the least surprising election results in Taiwanese history, Tsai Ing-wen has won the presidency in a landslide. Even more dramatically, the Democratic Progressive Party will take control of the legislature for the first time. Tsai’s victory is a devastating judgment on the presidency of Ma Ying-jeou.

With the imminent triumph of the Chinese Communist Party, Chiang Kai-shek moved his government to the island in 1949. For a quarter century Washington backed Chiang. Finally, Richard Nixon opened a dialogue with the mainland and Jimmy Carter switched official recognition to Beijing. Nevertheless, the U.S. maintained semi-official ties with Taiwan.

As China began to reform economically it also developed a commercial relationship with Taipei. While the ruling Kuomintang agrees with the mainland that there is but one China, the DPP remains formally committed to independence.

Beijing realizes that Tsai’s victory is not just a rejection of Ma but of China. Support even for economic cooperation has dropped significantly over the last decade.

Thus, China’s strategy toward Taiwan is in ruins. In desperation in November Chinese President Xi Jinping met Ma in Singapore, the first summit between the two Chinese leaders. Beijing may have hoped to promote the KMT campaign or set a model for the incoming DPP to follow.

Xi warned that backing away from the 1992 consensus of one China could cause cross-strait relations to “encounter surging waves, or even completely capsize.” While Tsai apparently plans no formal move toward independence, she also rejects the 1992 consensus of “one China, separate interpretations.”

As I point out in Forbes: “Washington is in a difficult position. The U.S. has a historic commitment to Taiwan, whose people have built a liberal society. Yet America has much at stake with its relationship with the PRC. Everyone would lose from a battle over what Beijing views as a ‘renegade province’.”

Washington should congratulate President-elect Tsai, but counsel Taipei to step carefully. Taiwan’s new government shouldn’t give the PRC any reason (or excuse) to react forcefully.

The U.S. should accelerate efforts to expand economic ties with Taiwan. Doing so would affirm America’s commitment to a free (if not exactly independent) Taiwan by other than military means.

America should continue to provide Taipei with weapons to enable it to deter if not defeat the PRC. At the same time, the new government should make good on the DPP’s pledge to make “large investments” in the military. It makes little sense for the U.S. to anger Beijing with new arms sales if Taipei is unwilling to spend enough to make a difference.

Washington should press friendly states throughout Asia, Europe, and elsewhere to communicate a consistent message to China: military action against Taiwan would trigger a costly reaction around the world. The mainland would pay a particularly high economic and political price in East Asia, where any remaining illusions of a “peaceful rise” would be laid to rest.

Finally, American officials should explore ideas for a peaceful modus vivendi. One possibility is for Washington to repeat its acceptance of “one China” and eschew any military commitment to Taiwan.

Taipei would accept its ambiguous national status and announce its neutrality in any conflicts which might arise in East Asia, including involving America and Japan. The PRC would forswear military means to resolve Taiwan’s status and reduce the number of missiles in Fujian targeting the island.

The objective would be to make it easier for both China and Taiwan to “kick the can down the road.” A final resolution of their relationship would be put off well into the future.

The ROC’s people have modeled democracy with Chinese characteristics. Hopefully someday the PRC’s people will be able to do the same.

In the meantime, President-elect Tsai is set to govern a nation which has decisively voted for change. However, if the PRC’s leaders fear they are about to “lose” the island—and perhaps even power at home—they may feel forced to act decisively and coercively. International ambiguity remains a small price to pay to avoid a cross-strait war.

Related Tags

The Current Climate of Extremes

What a day yesterday! First, our National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced that 2015 was the warmest year in the thermometric, and then the Washington Post’s Jason Samenow published an op-ed titled “Global warming in 2015 made weather more extreme and it’s likely to get worse.”

Let’s put NOAA’s claim in perspective. According to Samenow, 2015 just didn’t break the previous 2014 record, it “smashed” (by 0.16°C). But 2015 is the height of a very large El Niño, a quasi-periodic warming of tropical Pacific waters that is known to kite global average surface temperature for a year or so. The last big one was in 1998. It, too set the then-record for warmest surface temperature, and it was (0.12°C) above the previous year, which, like 2014, was the standing record at the time.

So what happened in 2015 is what is supposed to happen when an El Niño is superimposed upon a warm period or at the end year of a modest warming trend. If it wasn’t a record-smasher, there would have to be some extraneous reason why, such as a big volcano (which is why 1983 wasn’t more of a record-setter).

El Niño warms up surface temperatures, but the excess heat takes 3 to 6 months or so to diffuse into the middle troposphere, around 16,000 feet up. Consequently it won’t fully appear in the satellite or weather balloon data, which record temperatures in that layer, until this year. So a peek at the satellite (and weather balloon data from the same layer) will show 1) just how much of 2015’s warmth is because of El Niño, and 2) just how bad the match is between what we’re observing and the temperatures predicted by the current (failing) family of global climate models.

On December 8, University of Alabama’s John Christy showed just that comparison to the Senate Subcommittee on Space, Science, and Competitiveness. It included data through November, so it was a pretty valid record for 2015 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of the temperatures in the middle troposphere as projected by the average of a collection of climate models (red) and several different observed datasets (blue and green). Note that these are not the surface temperatures, but five-year moving average of the temperatures in the lower atmopshere.

El Niño’s warmth occurs because it suppresses the massive upwelling of cold water that usually occurs along South America’s equatorial coast. When it goes away, there’s a surfeit of cold water that comes to the surface, and global average temperatures drop. 1999’s surface temperature readings were 0.19°C below 1998’s. In other words, the cooling, called La Niña, was larger than the El Niño warming the year before. This is often the case.

So 2016’s surface temperatures are likely to be down quite a bit from 2015 if La Niña conditions occur for much of this year. Current forecasts is that this may begin this summer, which would spread the La Niña cooling between 2016 and 2017.

The bottom line is this: No El Niño, and the big spike of 2015 doesn’t happen.

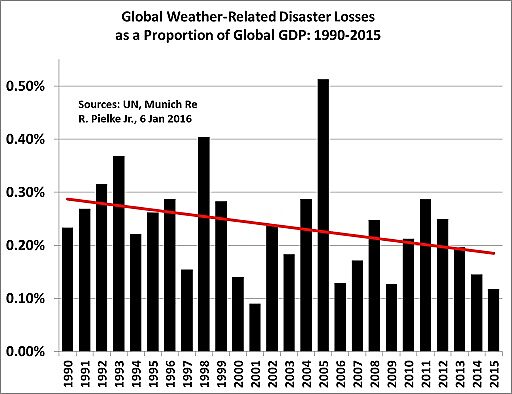

Now on to Samenow. He’s a terrific weather forecaster, and he runs the Post’s very popular Capital Weather Gang web site. He used to work for the EPA, where he was an author of the “Technical Support Document” for their infamous finding of “endangerment” from carbon dioxide, which is the only legal excuse President Obama has for his onslaught of expensive and climatically inconsequential restrictions of fossil fuel-based energy. I’m sure he’s aware of a simple real-world test of the “weather more extreme” meme. University of Colorado’s Roger Pielke, Jr. tweeted it out on January 20 (Figure 2), with the text “Unreported. Unspeakable. Uncomfortable. Unacceptable. But there it is.”

Figure 2. Global weather-related disaster losses as a proportion of global GDP, 1990–2015.

It’s been a busy day on the incomplete-reporting-of-climate front, even as some computer models are painting an all-time record snowfall for Washington DC tomorrow. Jason Samenow and the Capital Weather Gang aren’t forecasting nearly that amount because they believe the model predictions are too extreme. The same logic ought to apply to the obviously “too-extreme” climate models as well, shouldn’t it?

Related Tags

The Presumption of Innocence and ‘Making a Murderer’

In response to the wild popularity of the Netflix series, Making a Murderer, the Washington Post is running a series this week about the presumption of innocence for those readers who are hungry to learn more about the American criminal justice system. The Post invited me to submit a piece for the series and it is now available online. Here’s an excerpt:

Casual observers of our legal system will sometimes say that they would never plead guilty to a crime if they were innocent. An easy claim to make — but it is another thing when your freedom is actually on the line.

Imagine learning that the government has a “witness” who is willing to tell lies about you in court. And then your own attorney tells you that his best advice is for you to go into court, say you’re guilty and accept one year in prison instead of risking a 10-year prison sentence should the jury believe the lying witness. It’s an awful predicament for innocent people who get swept up in criminal cases. As William Young, then chief judge of the U.S. District Court in Boston observed in a 2004 opinion: “The focus of our entire criminal justice system has shifted away from trials and juries and adjudication to a massive system of sentence bargaining that is heavily rigged against the accused.”

Everyone is generally aware that some criminal cases go to trial and others are resolved by plea bargains, but most folks have no idea how lopsided the American criminal justice system has become. Only about five percent of the cases go to trial. One law professor says that finding a jury trial is about as likely as finding a hippopotamus in New York City. It’s not impossible…you just have to know where to look.