Congratulations to Neil Gorsuch, who will be sworn in Monday as the newest Supreme Court justice. Gorsuch’s mentor, Justice Byron White, liked to say that each new justice makes for a new court, and I look forward to the breath of fresh air, intellectual rigor, collegiality, and constitutional seriousness that Justice Gorsuch will bring. I’m also glad that our nation’s political debate can move beyond this toxic episode and that we won’t ever have to discuss nuclear options with regard to judges ever again.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Donald Trump, Syria, and the Power Problem

With his decision to launch missile strikes against an airfield in Syria, President Donald Trump has apparently learned a lesson that eventually dawns on all American presidents, especially in the post-Cold War era: with great power comes great responsibility. I call it the power problem.

The power problem was encapsulated in the exchange between then‑U.N. Ambassador Madeleine Albright and Gen. Colin Powell, at the time the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff:

What’s the point of having this superb military that you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?

Relieved of the burdens to justify U.S. military actions solely on the basis of our own national security interests, U.S. presidents and the foreign policy elites who advise them have gone searching for other reasons to use force. There will never be a shortage of aggrieved parties pleading for help. There is, however, a shortage of countries willing to help.

U.S. military power, and our willingness to use it, have discouraged others from possessing power of their own. They can reasonably claim that they lack the capability to act.

The United States doesn’t have that luxury. From the moment when a president arrives in the Oval Office, he possesses vast power, and few constraints on how it is used.

Using it wisely requires tremendous discipline, and a willingness to endure the criticisms of those who will accuse you of everything from callousness to mendacity — both when you act, and when you refuse to do so.

Trump’s repeated invocation of the doctrine “America First” suggested that he would not be swayed by such criticisms. And, in the past, he has suggested that the United States should not become involved in Syria’s civil war. In September 2013, for example, Donald Trump urged President Obama via Twitter not to attack Syria.

But now, just 77 days into his presidency, he has created an inevitable rejoinder for every successive foreign policy crisis, anywhere in the world: “Mr. President, you struck Syrian government forces in April 2017. Why are you not striking [insert name of petty tyrant here] in response to equally grievous actions against [petty tyrant’s people]?”

In his statement last night justifying the use of unilateral force against Bashar al-Assad’s forces in Syria, President Trump explained “It is in this (sic) vital, national security interest of the United States to prevent and deter the spread and use of deadly chemical weapons.”

It is a debatable point, and one that deserves to be debated. A new authorization for the use of military force (AUMF) would be a good place to start. There are risks, including conflict with nuclear-armed Russia. There are reasonable questions about what effect such strikes will have on Assad’s capacity to carry out similarly brutal killing by purely conventional means. And, lastly, having now introduced a very small increment of U.S. military power directly into the Syria conflict, some will wonder whether that signals a willingness to use much more. Those who castigated Barack Obama for refusing to intervene decisively in the Syrian civil war, including Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham, hope so. The question is whether President Trump, in the face of all this uncertainty, will be able to resist the temptation to escalate.

If he succumbs, Americans could find themselves sucked into yet another elective military quagmire in the Middle East.

Related Tags

U.S.-China Trade Deal Trumps U.S.-China Trade War

Amid increasing tensions between Washington and Beijing over economic and security matters, Chinese President Xi Jinping is in Florida today and tomorrow for meetings with President Trump. Although economic frictions between the world’s two largest economies are nothing new, the safeguards that have helped prevent those frictions from sparking an explosion and plunging the relationship into the protectionist abyss may no longer be reliable.

As I noted in this recent Cato Free Trade Bulletin:

Never have the U.S. and Chinese economies been more interdependent than they are today. Never has the value of the bilateral trade and investment relationship been greater. Never has the precarious state of the global economy required comity between the United States and China more than it does now. Yet, with Donald J. Trump ascending to power on a platform of nationalism and protectionism, never have the stars been so perfectly aligned for the relationship to descend into a devastating trade war.

What are those safeguards and why might they no longer be reliable?

First, U.S. multinational business interests that used to favor treading lightly with China, and provided a policy counterweight to U.S. import-competing industries advocating protectionism, have grown disillusioned by the persistence of policies that continue to impede their success in Chinese markets. Many think a more aggressive posture from Washington, even if that makes matters worse for them in the short run, is overdue.

Second, the pro-China-trade lobbies in Washington have grown sheepish in their advocacy on account of an economic study that went viral last year, ascribing massive U.S. jobs losses to trade with China, and because many fear political retribution from challenging Trump’s assumptions. Full-throated support for the relationship has become conditional support.

Third, now more than ever before, U.S. policymakers, media, and the public are less inclined to look at the bilateral economic relationship in isolation from the strategic and geopolitical aspects of the relationship. Segregating the issues in the past allowed us to focus on the win-win elements of trade, where there was broad enough agreement that mutual benefits could be derived, without being distracted by the issues where the United States and China are less likely to agree. Today, our economic frictions are viewed through the prism of our geopolitical differences – and that makes trade disputes more difficult to manage.

Fourth, probably more so than at any time since 1989, there is political “appetite” for a trade war. By that I mean that both Trump and Xi could extract some domestic political capital from the initiation of trade hostilities. Trump’s base and plenty of business and other interest groups believe China has it coming and—after all—as Trump suggests, China has much more to lose from a trade war given its $350 billion trade surplus with the United States. Meanwhile, Xi’s difficulties righting the Chinese economy, which has been suffering its slowest growth in 25 years, threaten him and the party with a crisis of legitimacy. Being able to blame domestic economic woes on protectionist or otherwise aggressive foreign policies would enable Xi to tap into a vast reservoir of Chinese nationalism, and would reduce the burdens of reform that confront him today. But make no mistake: a trade war between the United States and China would have profoundly adverse consequences in both countries and—depending on its course—could devastate the global economy. So there’s that.

Fifth, there are a number of legitimate gripes about Chinese AND U.S. trade policies that can no longer go unresolved. Beijing and Washington have been tightening the vices on one another’s companies in a number of different ways, and in some cases violating established rules. The focus of Trump’s criticism of China has been its currency policy, which has been a non-issue for nearly a decade. As is often the case, the politics lags the economics, but Chinese suppression of the value of its currency is simply irrelevant (as an economic matter). In fact, over the past two years, China has burned through $1 trillion of foreign reserves, purchasing Chinese renminbi on currency markets to prevent its value from depreciating further.

Among the list of potentially legitimate gripes made about Chinese policies are:

- Massive subsidization of industries

- Relatively high tariffs on goods imports and barriers to the provision of services by foreigners

- Widespread restrictions on foreign investment in a multitude of Chinese industries

- Forced transfer of technology imposed on foreign companies seeking to establish presence in China

- Indigenous innovation policies that grant preferences to companies that develop and register intellectual property in China

- Insufficient enforcement of intellectual property rights

- Barriers to digital trade, including web filtering and blocking, and restrictions on data flows and cloud computing

- The continued prominence of state-owned enterprises, which don’t face the same market constraints that private companies face

- Discriminatory application of China’s Anti-Monopoly law

- Scope for discriminatory application of China’s new Cybersecurity Law and National Security Law

Among the list of potentially legitimate gripes made about U.S. policies are:

- Continued discriminatory, non-market economy treatment of Chinese companies in U.S. antidumping cases

- Discriminatory application of the U.S. countervailing duty law, which punishes Chinese exporter (and U.S. importers) twice for the same alleged infraction

- Opaque and possibly discriminatory procedures at the U.S. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which reviews and can block proposed acquisitions of U.S. companies by foreigners on grounds of threats to national security

- Proposed expansion of CFIUS’s remit to include an economic security element, a food security element, and to extend covered transactions beyond acquisitions to include green field investments

- The unofficial, but commercially consequential blacklisting of acquisitions by and products made by certain Chinese information and communication technology companies

Many of the complaints about Chinese policies could have been addressed through the Trans-Pacific Partnership had President Trump not withdrawn the United States from that agreement. In fact, the TPP offered the clearest path to compelling favorable changes in China’s economic policies because China would have seen most of its major trade partners join the TPP, and would have had no better alternative than to join itself. That’s where the leverage (in the form of a carrot, not a stick) to compel China to play by the rules resided. And, for now at least, that leverage is squandered.

So, absent any obvious remaining carrots, some in Washington and around the country are encouraging a more strident tack with China. In today’s Washington Post, Rob Atkinson from the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, calls for what looks like some form of international sanctions against China. It seems a sure path to trade war.

A better idea, as articulated by my colleagues Simon Lester and Huan Zhu in this new paper, would be to launch bilateral trade negotiations to accomplish resolution of some or all of these issues in a very direct manner. Simon and Huan argue:

If the United States wants to promote the liberalization of Chinese trade and investment policy, it needs to engage with China in a more positive way. To this end, it should sit down with China and negotiate a new economic relationship, one that goes beyond the terms of the WTO. In particular, the United States should initiate formal negotiations on a trade agreement with China. Negotiations of this kind will be a challenge, especially with a president who has been so critical of China. However, negotiations offer the best hope for addressing concerns about China’s economic policies and practices.

Of course, like all trade negotiations, this one would be politically difficult. But considered against the alternatives, a bilateral trade deal is well worth serious consideration.

Related Tags

Nuclear Option Restores Senate Normalcy

Today’s removal of the filibuster — a parliamentary tool effectively requiring 60 votes to proceed with a vote on a matter — for Supreme Court nominees is the long overdue denouement of a process that began not with Senate Republicans’ refusal to vote on Merrick Garland, or even Harry Reid’s elimination of the filibuster for lower-court nominees in 2013, but with Reid’s unprecedented partisan filibusters in 2003. Recall especially the record 7 failed votes to end the filibuster of Miguel Estrada, who was blocked primarily because Democrats didn’t want President Bush to appoint the first Hispanic Supreme Court justice.

The Senate is now restored to the status quo ante, such that any judicial nominee with majority support will be confirmed. That’s a good thing.

RIP Partisan Filibuster (2003–2017)

Dollar-Denominated Cryptocurrencies: Flops and Tethered Success

A well-known obstacle to the greater popularity of Bitcoin as a medium of payment is the high volatility of its exchange value. This volatility results from its built-in quantity commitment: because the number of Bitcoins in existence stays on a programmed path, variations in the real demand to hold Bitcoin must be accommodated entirely by variations in its unit value. When demand goes up, there is no quantity increase to dampen the rise in price; and vice-versa for a fall in demand.

Not surprisingly, several cryptocurrency developers have thought of creating a cryptocurrency with a price commitment — namely a pegged exchange rate with the US dollar — rather than a quantity commitment, in hopes of greater popularity. The aim is to create a system in which dollar-denominated payments can be made with the ease, security, and low cost of Bitcoin payments, but without the exchange-rate risk.

The development of “Blockchain 2.0” platforms has enabled the launching of a variety of new digital assets, including such dollar-pegged (and euro-pegged and gold-pegged) currencies. As we will see, the histories of early (2014–2016) dollar-pegged cryptocurrencies show a series of flops. But one project, Tether, has become a late-blooming success. Tether had $55 million in circulation as of March 29, 2017, making it the #13 largest cryptocurrency. To keep this size in perspective, a brick-and-mortar US institution with $55 million in deposits is a tiny bank or a mid-size credit union, and Tether is currently only 1/300th the size of Bitcoin.

The Tether white paper explains in more detail the motivation for developing a dollar-pegged cryptocurrency by listing advantages to individuals using it for dollar-denominated transactions rather than using dollars held in “legacy bank” accounts:

- Transact in USD/fiat value, pseudonymously, without any middlemen/intermediaries

- Cold store USD/fiat value by securing one’s own private keys

- Avoid the risk of storing fiat on [cryptocurrency] exchanges – move cryptofiat in and out of exchanges easily

- Avoid having to open a fiat bank account to store fiat value

In sum, “Anything one can do with Bitcoin as an individual one can also do with” a dollar-pegged cryptocurrency, namely, “avoid credit card [or debit card] fees,” maintain greater privacy, “remit payments globally” more cheaply, and access blockchain financial services.

But what is the claimed advantage over using Bitcoin? It is the expectation of wider acceptance in payments, because of the advantages to merchants of accepting a dollar-pegged cryptocurrency over accepting Bitcoin in a US-dollar-dominated economy:

- Price goods in USD/fiat value rather than Bitcoin (no moving conversion rates/purchase windows)

- Avoid conversion from Bitcoin to USD/fiat and associated fees and processes

The Flops

First we consider the projects that have flopped. Three projects were launched in September 2014: CoinoUSD, NuBits, and BitUSD. Their pegging mechanisms were different, and are difficult to describe briefly (partly because they were not all entirely transparent), but two common features are important to note.

- The rate-pegging mechanisms were not programmed into a source code, like Bitcoin’s quantity commitment, but relied on non-programmed policy actions by a trusted central authority.

- None used the traditional currency pegging method of having the issuer hold reserves in physical dollars or dollar-denominated debt securities. (On the NuBits mechanism see this critique by a BitUSD promoter. On the BitUSD mechanism see this critique by the CoinoUSD developer.)

We can examine the fortunes of each project by looking at its price and “market capitalization” (value-in-circulation) history on the cryptocurrency tracking site CoinMarketCap.com.

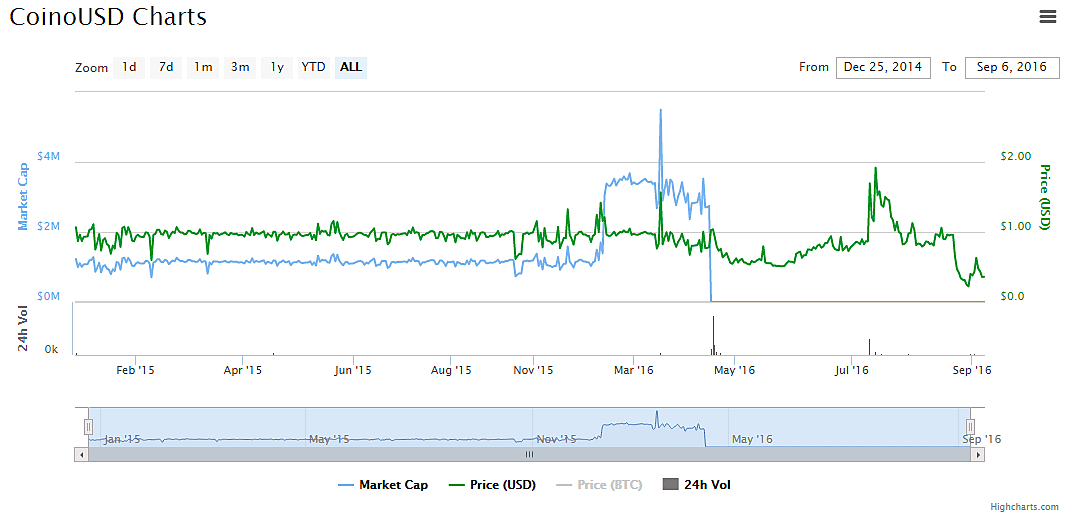

CoinoUSD

CoinoUSD, which began trading in December 2014, was developed by a for-profit payments firm called Coinomat and built on the blockchain of the NXT cryptocurrency. (In November 2014 NXT was the #6 cryptocurrency with a market cap of $19 million; currently it ranks #38 with a market cap around $13 million.) CoinoUSD reached a market cap plateau of $2.7 million in early 2016, but shut down in early 2016, due to a “payout glitch” that flooded customers with free CoinoUSD units, making it impossible to maintain the exchange value at $1. Coinomat announced a reboot in which the erroneous payout would be reversed and said, “NXTUSD will replace CoinoUSD completely, and enhance it,” but this appears not to have happened. Since then it has had a market cap of zero, and its webpage at the Coinomat site declares it “disabled until further notice.”

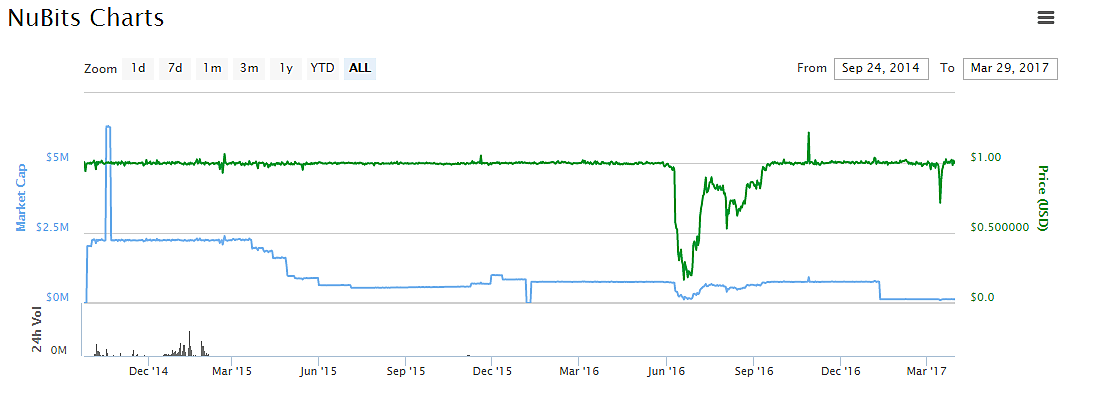

NuBits

The history of NuBits, also a for-profit enterprise, shows that it gained only a similarly small market foothold. Its market cap plateaued early on below $2.5 million, and since April 2015 has remained below $1 million. In June 2016 NuBits had a devaluation crisis, with the price falling to 20 cents. Its rate-pegging intervention mechanism, despite claiming many layers of reinforcement, was not robust and failed. Although the price later returned to par, today NuBits shows very little market activity. Since January 2017 the market cap has hovered around only $135,000, with daily trading volume in the neighborhood of $2000.

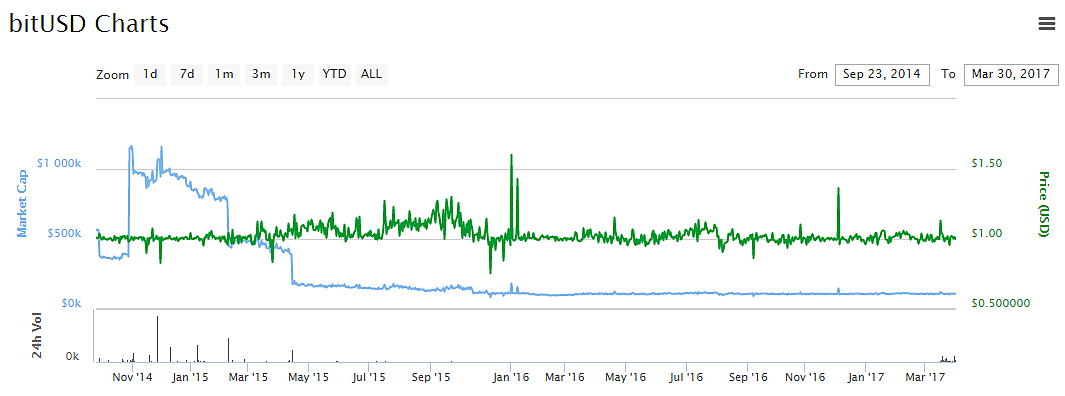

BitUSD

BitUSD is built on the blockchain platform of the cryptocurrency BitSharesX. Its highest market cap plateau was around $1 million soon after introduction, but it fell to below $200,000 in April 2015 and is currently less than $110,000.

BitUSD uses a novel pegging system that so far has proven robust. A piece promoting BitUSD emphasizes that “the bitUSD is an asset that is not backed by real dollar in someone’s bank account.” (It claims this a virtue: “We cannot trust anyone to hold and secure a physical asset so that people can redeem it eventually. History has repeatedly shown: It doesn’t work!” In fact, history shows the major banks in unhampered banking systems routinely justifying the public’s trust by redeeming their liabilities on demand for decades. Paypal works on the same supposedly non-working model, backed by Paypal’s dollar deposits at Wells Fargo Bank.) By contrast, BitUSD are created through collateralized forward currency contracts. The network provides an escrow service that credibly ensures repurchase (or “redemption”) of the BitUSD at or near par. Someone who wants to acquire BitUSD, say in order to buy from a seller who prefers a dollar-denominated medium of exchange, offers a contract: so many BitShares (hereafter BTS) for a certain amount of new BitUSD. Under the BitShare network rules, the acquirer must not only pay at the outset in BTS but also agree to post collateral in BTS equal to the value of the bid. If the bid is accepted by another network participant, explains the BitUSD white paper, “the collateral and purchase price are held by the network until the BitUSD is redeemed” by some third party repurchasing it. The acquirer of BitUSD thus puts 200% collateral into a contract “that only allows access to these BTS when the BitUSD are paid back.” In effect the acquirer is shorting the dollar price of BTS.

Note that the new BitUSD units are initially 200% collateralized not in dollar-denominated assets, but in BTS. If BTS fall 25% or more against the dollar, such that the value of the BTS collateral declines to 150% or less of the value to be repaid, under the network rules redemption can be compelled by any BitShares miner who “enforces a margin call.” (It should be noted that to enforce the collateral rules, the BitShares network relies on trusted human agents to inform it about the current $ price of BTS.) The system then “uses the backing BitShares to repurchase the BitUSD…thereby redeeming it.” Conversion back into dollars is thus not always at the initiative of the holder, as it is for a holder of ordinary demandable bank liabilities. Instead a BitUSD holder faces a risk of “forced settlement.” If the value of BTS falls so quickly “that the margin is insufficient, then the market price of the BitUSD may fall slightly below parity for a short time if there is insufficient demand for BitUSD relative to the supply of sellers.”

The white paper concludes: “The critical thing to understand is that BitUSD is an asset used to hedge a position in BitShares against changes in the price of USD and is not supposed to have an exact 1:1 exchange rate with USD.” A close look at the chart indeed shows that the price of 1BitUSD has not been exactly $1. It has vibrated around $1 but has not experienced any lasting devaluation. Nonetheless its clientele has declined and is currently small. No doubt this reflects in part the declining popularity of BTS, its market cap having fallen from more than $60 million in September 2014 to around $15 million today.

The Success: Tether

Now to the success story. Tether was launched in February 2015. In contrast to the previous contenders, as the chart shows, it started slowly and has grown in market cap. The series of discrete steps in its market cap path indicates that there have been a series of large purchases. The most recent step, on Wednesday, March 29, 2017, raised the value in circulation to $55 million from $45 million. Logically these are not speculative position-takings, because there are no capital gains to be had so long as the price per tether remains solidly pegged (or “tethered”) to $1. And Tether has in fact successfully maintained a steady peg throughout its history with only one small and brief blip. The steps are presumably big acquisitions for transaction use. Transactions volume in recent weeks has been running mostly in the neighborhood of at $20–40 million per day.

Tether transfers are executed using the Bitcoin blockchain. Tether’s pegging mechanism is also not programmed into a source code, but it is the traditional one: the issuer holds dollar-denominated reserve assets and pledges to redeem Tethers on demand. (Euro-Tethers have recently been introduced, but I focus here on dollar-Tethers.) According to the official FAQ, “Tether Platform currencies are 100% backed by actual fiat currency assets in our reserve account. Tethers are redeemable and exchangeable pursuant to Tether Limited’s terms of service. The conversion rate is 1 tether USD₮ equals 1 USD.”

The parent Tether firm, in other words, operates like a currency board: It holds 100%+ dollar-asset backing, and passively swaps Tethers for dollars and back again. Like a currency board, it can earn interest income by holding some of its dollar-denominated assets in interest-bearing form. The Tether white paper reveals that Tether’s dollar reserves are currently held in accounts at two major Taiwanese commercial banks: Cathay United Bank and Hwatai Bank. (Why these particular banks? “They also provide banking services to some of the largest Bitcoin exchanges globally,” they are okay with Tether’s business model, and they are experienced at compliance with Know-Your-Customer and Anti-Money-Laundering regulations.) It adds that “additional banking partners are being established in other jurisdictions” to reduce political risk of the accounts being frozen. Tether is thus not a “100% reserve” institution in the sense of a money warehouse holding 100% literal cash reserves (which would mean Federal Reserve notes in a vault).

How does a potential purchaser of Tether verify the 100% backing claim? The website declares: “Our reserve holdings are published daily and subject to frequent professional audits. All tethers in circulation always match our reserves.” A webpage does give dollar values for assets and liabilities, but does not identify the auditors or provide copies of the audit reports, so the claim of being “fully transparent” is somewhat exaggerated. The transparency is as great as that of historical note-issuing banks, however. And perhaps the important test of trustworthiness is that Tethers have in practice been redeemed every day at par for about two years.

Dollar-pegged cryptocurrencies, by contrast to Bitcoin, separate blockchain-secured payments from the speculative holding of an irredeemable private currency. Thus they provide a potential window for learning how much of the demand for cryptocurrencies is transactional, and how much is speculative. The competition among dollar-pegged cryptocurrencies provides something of a market referendum on the relative credibility of alternative pegging arrangements. The much larger size achieved by Tether suggests (though not definitively, because other factors are also in play) a popular verdict that its pegging mechanism is more credible than those of CoinoUSD, Nubits, or BitUSD. It will be interesting to watch Tether’s progress from this point on, and to observe whether its model is copied by other entrants.

Related Tags

Poor Defendants Should Get to Choose Their Lawyers Too

Americans may take for granted that if they’re ever accused of a crime, they can choose their own attorney to represent them. The Supreme Court has ruled that Americans have a right to counsel in serious criminal cases, and nobody seriously argues that the government should make that important decision for us.

Yet that is exactly what happens across the country when defendants are too poor to hire their own attorneys. While other countries such as the United Kingdom have long allowed indigent defendants to choose their own lawyers, American jurisdictions historically restrict that choice to either a court-appointed lawyer or an assigned public defender.

In 2010, the Cato Institute published a study, Reforming Indigent Defense, which proposed a client choice model where poor persons accused of crimes would be able to choose their own attorney to represent them in court. If the accused opted for the public defender, he could make that choice, but if he wanted to explore other options, he could do that also. The Texas Indigent Defense Commission became aware of the Cato report and decided to give it a try with a pilot program in Comal County, near San Antonio. The program went into operation in 2015.

Today, the Justice Management Institute released an evaluation based on two years of data from the Comal Client Choice program. The report, called The Power of Choice: The Implications of a System Where Indigent Defendants Choose Their Own Counsel, suggests that the program is working as well or better than the old system across a variety of metrics.

The JMI study looks at four factors to assess the viability of the Comal program:

- Does the model impact the quality of representation?

- Does the model produce a higher level of satisfaction and procedural justice?

- Does the model impact case outcomes?

- What is the impact of the model on overall cost and efficiency?

The study compares the results of Client Choice participants with the representations of defendants who chose to use the pre-existing court-appointment system.

While some aspects of representation were the same for both groups (for instance, client assessments of how hard their lawyers worked were not statistically distinguishable), participants in the Client Choice program were able to meet with their lawyers more quickly, had a stronger sense of fairness, and were more likely to either plead to lesser charges or exercise their right to trial than their peers. The report also finds that the Client Choice program did not increase costs in the system.

Perhaps as important as any objective metric, a majority of defendants who were offered the ability to choose their own attorney opted to do so, suggesting that giving indigent defendants some agency in their choice of representation has a value in itself. Freedom of choice matters to people.

In too many jurisdictions, indigent criminal defense is in a state of crisis. Texas is in the vanguard with its Client Choice program. Hopefully these promising results will encourage more jurisdictions to consider injecting choice and market principles into their indigent defense systems.

Negotiating Trade with China

The meetings today and tomorrow between President Trump and President Xi in Florida are unlikely to delve deeply into substantive policy issues. Rather, the focus will be on establishing a good relationship between the two leaders, in order to lay the foundation for future cooperation. Trade and security tensions between the two countries will be discussed, but probably only in broad terms.

But difficult talks on the substance of these issues are inevitable. The question is how to approach the disagreements most productively.

On trade, there have been long-standing concerns from U.S. industry about a number of Chinese trade practices (including allegations of intellectual property theft, high tariffs, discriminatory regulations, non-commercial behavior by state-owned companies, and overcapacity in the production of steel and other goods). To date, the U.S. government approach to addressing these concerns has consisted largely of litigation at the WTO, trade remedy cases (mainly anti-dumping and countervailing duties), and high-level dialogues between the two governments, but these actions have failed to resolve most of the concerns. Litigation at the WTO can be helpful, but only in those areas where the WTO has rules, and there are many gaps in those rules; trade remedy cases impose tariffs that harm Americans, and do little to resolve the underlying problems with Chinese trade practices; and the dialogues tend to be broad, vague, and unenforceable.

The Trump administration has hinted at adding new unilateral trade restrictions into the mix (beyond trade remedy cases), but such measures are likely to lead to retaliation by China, which could escalate the current tensions into a tit-for-tat trade war. If that happens, the big losers will be ordinary Americans and Chinese who would feel the brunt of any tariff increases.

In a Free Trade Bulletin published yesterday, my colleague Huan Zhu and I argue that a better approach to these issues would be to sit down with China and negotiate a formal trade agreement to deal with as many of these issues as possible. For example, with regard to existing tariff levels, the two countries could agree to an across the board lowering of tariffs, a standard feature of trade agreements.

There will be a number of political obstacles to such a negotiation, and don’t expect any big announcement about it at the Trump-Xi meeting. But as the U.S. government develops its trade policy over the coming months, it may begin to realize the limitations of the alternative approaches to addressing concerns about China. Trump administration officials have emphasized that the trade deals it negotiates will be bilateral, rather than multilateral. Why not try to negotiate a bilateral agreement with China, one of our biggest trading partners, and the one that is the source of so many trade concerns?