During his SOTU address last week, the president declared it a national goal to double our exports over the next five years. As my colleague Dan Griswold argues (a point that is echoed by others in this NYT article), such growth is probably unrealistic. But with incomes rising in China, India and throughout the developing world, and with huge amounts of savings accumulated in Asia, strong U.S. export growth in the years ahead should be a given—unless we screw it up with a provocative enforcement regime.

The president said:

If America sits on the sidelines while other nations sign trade deals, we will lose the chance to create jobs on our shores. But realizing those benefits also means enforcing those agreements so our trading partners play by the rules.

Ah, the enforcement canard!

One of the more persistent myths about trade is that we don’t adequately enforce our trade agreements, which has given our trade partners license to cheat. And that chronic cheating—dumping, subsidization, currency manipulation, opaque market barriers, and other underhanded practices—the argument goes, explains our trade deficit and anemic job growth.

But lack of enforcement is a myth that was concocted by congressional Democrats (Sander Levin chief among them) as a fig leaf behind which they could abide Big Labor’s wish to terminate the trade agenda. As the Democrats prepared to assume control of Congress in January 2007, better enforcement—along with demands for actionable labor and environmental standards—was used to cast their opposition to trade as conditional, even vaguely appealing to moderate sensibilities. But as is evident in Congress’s enduring refusal to consider the three completed bilateral agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea (which all exceed Democratic demands with respect to labor and the environment), Democratic opposition to trade is not conditional, but systemic.

The president’s mention of enforcement at the SOTU (and his related comments to Republicans the following day that Americans need to see that trade is a two way street — starts at the 4:30 mark) indicates that Democrats believe the fig leaf still hangs. It’s time to lose it.

According to what metric are we failing to enforce trade agreements? The number of WTO complaints lodged? Well, the United States has been complainant in 93 out of the 403 official disputes registered with the WTO over its 15-year history, making it the biggest user of the dispute settlement system. (The European Communities comes in second with 81 cases as complainant.) On top of that, the United States was a third party to a complaint on 73 occasions, which means that 42 percent of all WTO dispute settlement activity has been directed toward enforcement concerns of the United States, which is just one out of 153 members.

Maybe the enforcement metric should be the number of trade remedies measures imposed? Well, over the years the United States has been the single largest user of the antidumping and countervailing duty laws. More than any other country, the United States has restricted imports that were determined (according to a processes that can hardly be described as objective) to be “dumped” by foreign companies or subsidized by foreign governments. As of 2009, there are 325 active antidumping and countervailing duty measures in place in the United States, which trails only India’s 386 active measures.

Throughout 2009, a new antidumping or countervailing duty petition was filed in the United States on average once every 10 days. That means that throughout 2010, as the authorities issue final determinations in those cases every few weeks, the world will be reminded of America’s fetish for imposing trade barriers, as the president (pursuing his “National Export Initiative”) goes on imploring other countries to open their markets to our goods.

Rather than go into the argument more deeply here, Scott Lincicome and I devoted a few pages to the enforcement myth in this overly-audaciously optimistic paper last year, some of which is cited along with some fresh analysis in this Lincicome post.

Sure, the USTR can bring even more cases to try to force greater compliance through the WTO or through our bilateral agreements. But rest assured that the slam dunk cases have already been filed or simply resolved informally through diplomatic channels. Any other potential cases need study from the lawyers at USTR because the presumed violations that our politicians frequently and carelessly imply are not necessarily violations when considered in the context of the actual rules. Of course, there’s also the embarrassing hypocrisy of continuing to bring cases before the WTO dispute settlement system when the United States refuses to comply with the findings of that body on several different matters now. And let’s not forget the history of U.S. intransigence toward the NAFTA dispute settlement system with Canada over lumber and Mexico over trucks. Enforcement, like trade, is a two-way street.

And sure, more antidumping and countervailing duty petitions can be filed and cases initiated, but that is really the prerogative of industry, not the administration or Congress. Industry brings cases when the evidence can support findings of “unfair trade” and domestic injury. The process is on statutory auto-pilot and requires nothing further from the Congress or president. Thus, assertions by industry and members of Congress about a lack of enforcement in the trade remedies area are simply attempts to drum up support for making the laws even more restrictive. It has nothing to do with a lack of enforcement of the current rules. They simply want to change the rules.

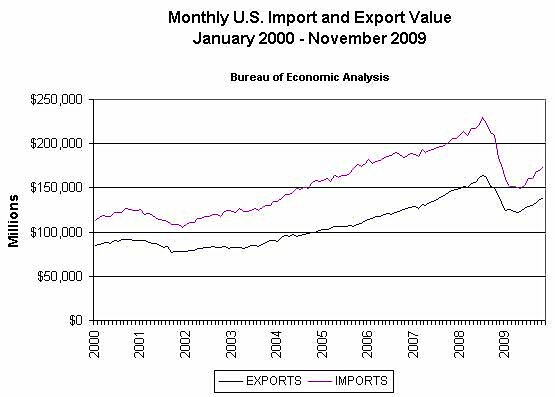

In closing, I’m happy the president thinks export growth is a good idea. But I would implore him to recognize that import growth is much more closely correlated with export growth than is heightened enforcement. The nearby chart confirms the extremely tight, positive relationship between export and imports, both of which track similarly closely to economic growth.

U.S. producers (who happen also to be our exporters) account for more than half of all U.S. import value. Without imports of raw materials, components, and other intermediate goods, the cost of production in the United States would be much higher, and export prices less competitive. If the president wants to promote exports, he must welcome, and not hinder, imports.