My new op-ed in the Examiner looks at the interstate migration of top-earning households. I argue that states such as New York lose a lot when their high taxes drive out top earners, including losing their incomes, investments in startups, and entrepreneurial and charitable activities.

Many states are figuring this out, and my NRO op-ed last week discusses the recent wave of income tax cutting. While the leaders of monopoly Democratic states, such as New York, seem oblivious to the chronic damage their states are suffering from out-migration, leaders in states such as Iowa and Nebraska are doing something about it with pro-growth tax reforms. These issues are discussed in the forthcoming Fiscal Report Card on America’s Governors.

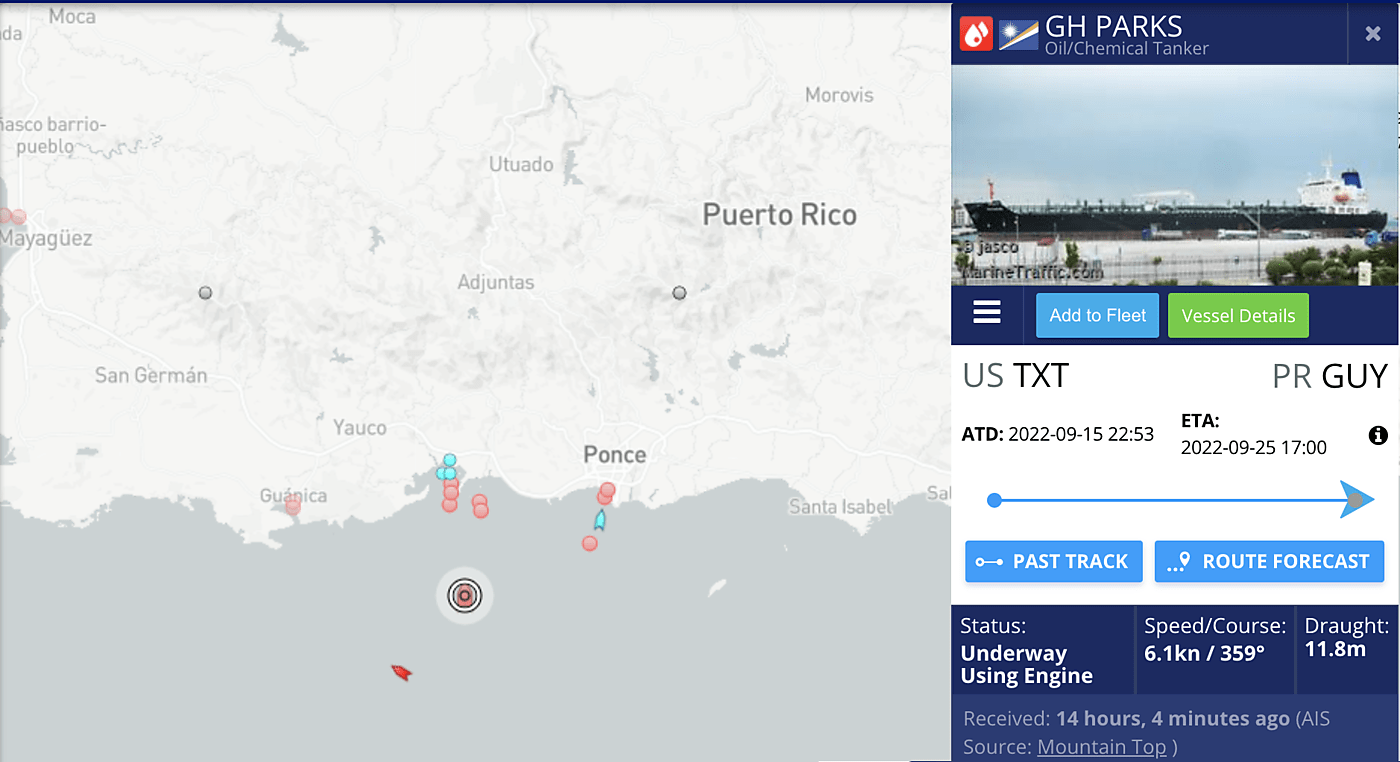

The chart shows something interesting about the interstate migration data, which is available from the IRS. For each state, I calculated the ratio of in-migration to out-migration. States losing households have ratios of less than 1.0, and states gaining households have ratios of more than 1.0. For example, New York gained 147,324 households in 2020 and lost 276,550, for a ratio of 0.53. Meanwhile, Florida gained 337,375 and lost 256,190, for a ratio of 1.32.

The IRS splits out households earning more than $200,000, and I calculated the migration ratios separately for this group. On the chart, each state is a dot. The horizontal axis is the ratio for all households, and the vertical axis is the ratio for households over $200,000. I labeled some of the states gaining and losing the most households.

Here’s what interesting. For the states gaining a lot of households, the ratio for top-earners is always higher than the overall ratio. Florida’s overall ratio is 1.32 but its top-earner ratio is 2.72. So Americans generally like Florida, but top earners super like Florida. This pattern is the same for all the states substantially above the line in the chart, including Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Maine, Montana, and South Carolina.

For states suffering out-migration, it is flipped. New York’s ratio for all households is 0.53, but for top-earning households is 0.33. That means New York gains one household for each two it loses overall, but it gains one household for each three it loses within the top-earning group. This pattern is true for the other large out-migration states—that is, the states on the far left below the line, including Illinois and California.

The out-migration states are doing something to drive out their residents, and those things are particularly toxic to top earners. State policymakers should figure out what those things are and fix them.