President Biden’s critics are sometimes too quick to dismiss his claim that U.S. gasoline prices have risen this year largely because of Putin’s war on Ukraine. For example, “FOX Business host Maria Bartiromo pushed back Friday on President Biden blaming Russian President Vladimir Putin, COVID-19 and oil companies for record gas prices, arguing on ‘America’s Newsroom’ the U.S. inflation timeline started ‘way before Russia invaded Ukraine’.”

That was misleading in two respects. First, questions about what happened to gasoline prices in the past three months are not at all the same as the “inflation timeline” for all consumer prices since early 2021. What happened to the price of crude oil in 2022 does not explain inflation in general (though energy costs affect a wide array of farm and industrial products and their distribution) and it certainly does not explain what happened last year.

Many year-to year inflation numbers from 2020 to 2021 inevitably surged last year because of “baseline effect” as deflated pandemic prices bounced back when the world economy reopened. Texas crude oil thus rose from an $16.55 a barrel in April 2020 (which is why U.S. production shut down) to $61.70 in April 2021. We might call that inflation and blame it on the new President, but only if anyone imagines U.S. oil producers could have survived on $16.55 a barrel.

Second, the price of crude oil on futures markets naturally reflected prudent hedging (and speculating) against the risk of evasion long before that invasion occurred on February 24. A January 7 New York Times report offered a map showing “Russian forces now surround Ukraine on three sides, and Western officials fear a military operation could start as soon as this month.”

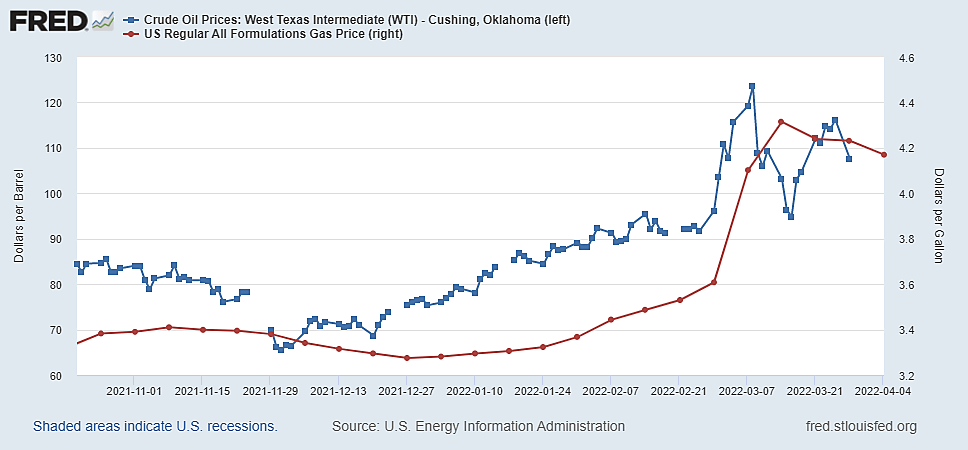

The graph shows that the spot price of WTI crude was below $80 a barrel before that January 7 news came out then drifted above $90 before as the risk grew stronger each week. Crude oil then spiked above $110–120 at times since the February 24 invasion. Unsurprisingly (since crude is half the cost of gasoline), prices of gasoline and diesel fuel also jumped much higher since the invasion, all around the world.

Gasoline prices (set by contract) rise and fall more gradually than the daily spot prices crude oil, following crude prices with a lag. To expect retail prices of gasoline to change up and down every day with yesterday’s spot price of crude is something that could only make sense to politicians.

There is really no room for doubt that Russia’s war on Ukraine raised the retail price of a gallon of gasoline by at least a dollar in the U.S. (and much more in Europe). But expensive energy is far more problematic for industry, transportation, and farming (and therefore for consumers) than the mere “price at the pump.”