Trade ministers from more than 150 countries are gathering today in Geneva, Switzerland, for a three-day ministerial meeting of the World Trade Organization. These meetings happen every two years or so. No great breakthroughs are expected at this one, but it does offer an opportunity to take stock of where the WTO and world trade stand a decade after China’s entry into the organization and the launch of the still ongoing Doha Development Round.

News from the first day is a reminder that the organization can still deliver real trade liberalization. Forty-two members, including the United States, announced just a few hours ago that they had revised the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement to open up an estimated $100 billion in annual government purchases to more international competition, potentially saving taxpayers billions of dollars a year.

The revised GPA will also give U.S. companies a fairer shot at winning contracts to supply goods and services to foreign governments. It is a partial antidote to the protectionist trend in the United States and elsewhere to restrict government spending to domestic suppliers in the misguided view that that will stimulate domestic demand.

The Doha Round may be stalled, but global trade has continued to expand. Even with the sharp downturn in trade during the recent Great Recession, in the decade since 2001 global trade volume has increased 44 percent, according to the WTO web site. Trade growth has been especially robust in East Asia and other emerging markets. The anti-market protestors can take some satisfaction in the lack of progress in negotiations, but globalization marches on.

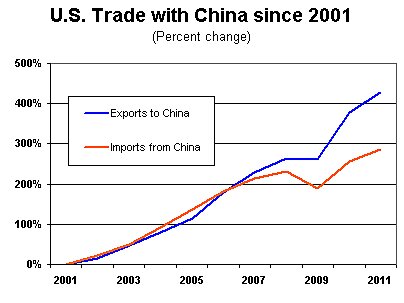

A decade after its entry into the organization, China remains a mixed economy with significant trade barriers, but it has become one of the more open major developing economies. And it is now subject to the WTO dispute settlement mechanism and other disciplines that keep its economy more open than it would be outside the organization. There were dire warnings about a flood of imports from China if we allowed it to join, but in the past decade U.S. exports to China have grown significantly faster than imports from China.

As the chart below shows, since China’s entry into the WTO in December 2001, U.S. exports of goods to China have grown more than five-fold while U.S. imports of Chinese goods have grown four-fold. The robust export growth reflects both the growth of the Chinese economy and the decline of its trade barriers against goods of major export interest to the United States. For that we can give the WTO a major share of the credit.

As I’ve written elsewhere, there are other good reasons to see the WTO as a positive if modest factor in the global economy–to the benefit of the United States and the freedom to trade across the world.