“Federal Reserve actions seem to have important effects on the macroeconomy, but precisely why is one of the most poorly understood and contentious issues in economics.” — Ben Bernanke (1988)

The Wall Street Journal editors advise “dialing down what are now $120 billion a month in long-term bond purchases” (which would still amount to quantitative easing) and they suggest, “The economy also almost certainly can absorb an increase of 0.25 percentage point in the target Fed funds rate much sooner than the Fed seems to believe.” Probably so, but what is the point? Why are higher interest rates supposed to result in lower inflation, since Irving Fisher taught us long ago that interest rates can only stay higher if inflation stays higher.

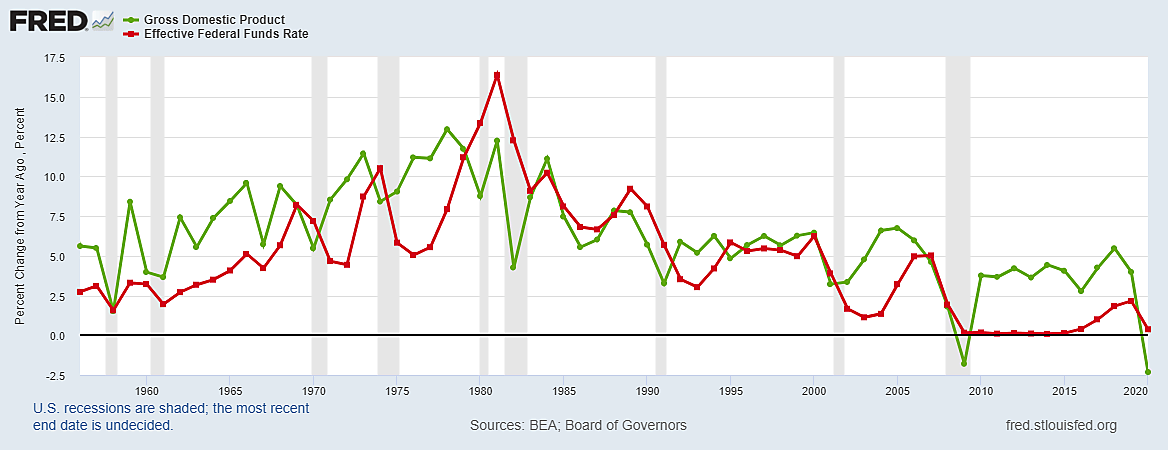

Most economic journalists and their readers assume a higher central bank interest rate would slow the growth of total spending and thus reduce future inflation. But look at the graph.

The red line shows the history of the fed funds rate, using yearly averages for emphatic simplicity.

The green line shows annual changes in nominal GDP (NGDP), roughly the sum of real growth plus inflation.

Contrary to the conventional wisdom that a higher fed funds rate will slow the growth of aggregate demand (including inflation), the graph shows both series moving up and down together – with the fed funds rate typically moving a year after peaks and troughs in GDP.

The fed funds rate peaked 1–4 years after NGDP growth did – at 8.2% in 1969, 10.5% in 1974, 16.4% in 1981, and 9.2% in 1989. What did such routine spikes in central bank interest rates have to do with keeping inflation down? The Volcker Fed is nowadays lionized for fighting inflation with a 16.4% fund rate in 1981. But if that was a durable cure, why was the funds rate still 10.2% in 1984 and 9.2% in 1989?

By the journalistic definition of “tight money,” the Fed was tightest from 1973 to 1984 when the fed funds rate averaged 9.7% and Nominal GDP growth averaged 10.1%. Yet this was, of course, a period of unprecedented peacetime inflation.

By the journalistic definition of “easy money,” monetary policy was most “stimulative” from 2009 to 2020 with an average fed funds rate of 0.6%. Yet NGDP growth averaged only 3% a year. The economy grew so slowly over the past decade there was not enough loan demand to support real interest rates much above zero.

Those now arguing in favor of a higher federal funds rate and a lower inflation rate might ultimately have to choose between those inconstant objectives.